Assyrian campaigns against northwest iran, elam and the medes

Twenty-one years after Tiglath-Pileser III’s Iranian campaign, king Rusa I of Urartu (730-714 BCE) attacked Manna in 716 BCE, capturing 22 of their strong-holds. Sargon II counterattacked against the Urartians, defeating them in 715-714 BCE (Melville 2016, 116-140). The Manna kingdom was now increasing-ly transformed into Assyria’s client state. Nevertheless, Sargon II was obliged to campaign against Manna to re-assert Assyria’s authority. This campaign was soon followed by the Assyrian organization of three new provinces, one of which was officially designated as Madaj or Media. It is possible that the etymology for Lake “Urumiah” in Iranian Azerbaijan may be traced to Aramaic “miah/ma(h)” (lake, water).The Assyrians were also facing serious challenges further to their south. Bab-ylon, which was seeking independence from the Assyrians became the military ally of Elam (in modern day southwest Iran) by the 750s BCE. The Elamite king Humban-nikash I (r. 743-717 BCE) fought the Assyrian army at Der fortress (in modern southern Iraq) in 720 BCE which is traditionally credited as an Elamite victory (Carter and Stolper, 1984, 45), however Melville suggests that the Assyr-ians held their ground but then withdrew as the Babylonian army led by Mero-dach-baladan (or Marduk-apla-iddina II, r. 722-710 BCE, 703-702 BCE) arrived late into the battle (2016, 64). In the meantime, the Medes and numerous other Iranian tribes remained defiant of Assyrian authority. In response, Sargon II at-tacked deep into Iran in 713 BCE, reaching as far as “the far mountain of Bikni” (Mount Demavand near modern Tehran), to then possibly establish a number of military outposts in the region. Consistent with the military policy of his prede-cessors Sargon II targeted the equestrian base of the Medes who were forced to cede large numbers of horses to the Assyrians in 713 BCE (Fuchs 1994, 191-194). These successes allowed Sargon II to invade Elam in 710 BCE, forcing its king Shutruk-Nahhunte (r. 717-699 BCE) to flee with Merodach-baladan who was al-so forced to escape as his armies proved incapable of defending Babylon’s cities (Dandamaev and Lukonin, 1989, 48).

Rise of the mede dynasty, clashes with assyria and military developments

When Rusa invaded northwest Iran in 716 BCE, he encouraged Daiaukku, cited as Dahyuka of the Misi (a Mannaean province as cited in Sargon’s records) to break off his ties from Assyria (Diakonoff 1985, 83, 90). The general academic consensus is that Daiaukku is the same person known as Deioces of the Medes (Schmitt 1994, 226-227) who succeeded in forming the first independent Iranian kingdom in the 8th century BCE (Dandamaev and Lukonin 1989, 47), as discussed further below. Traditional scholarship placed Deioces’ rule in 700-647 BCE (22) years) but these dates are disputed (Dandamaev and Medvedskaya, 2006). Deioces organized a royal guard (Briant 2002, 25) and built his capital at Ecbatana, which as Polybius has interestingly noted lacked fortifications(4). While this was the first political attempt towards a unified Iranian kingdom, scholars no longer agree with Herodotus assertion that he united all of Mede tribes into a single kingdom (Radner 2013, 453-454). Given the lack of certitude with respect to the exact chronol-ogy Deioces’ reign it is unclear as to when (and by which Assyrian king) he was exiled. The general consensus has been that Deioces was exiled with much of his family to Hamath in Syria (Schmitt 1994, 226-227).

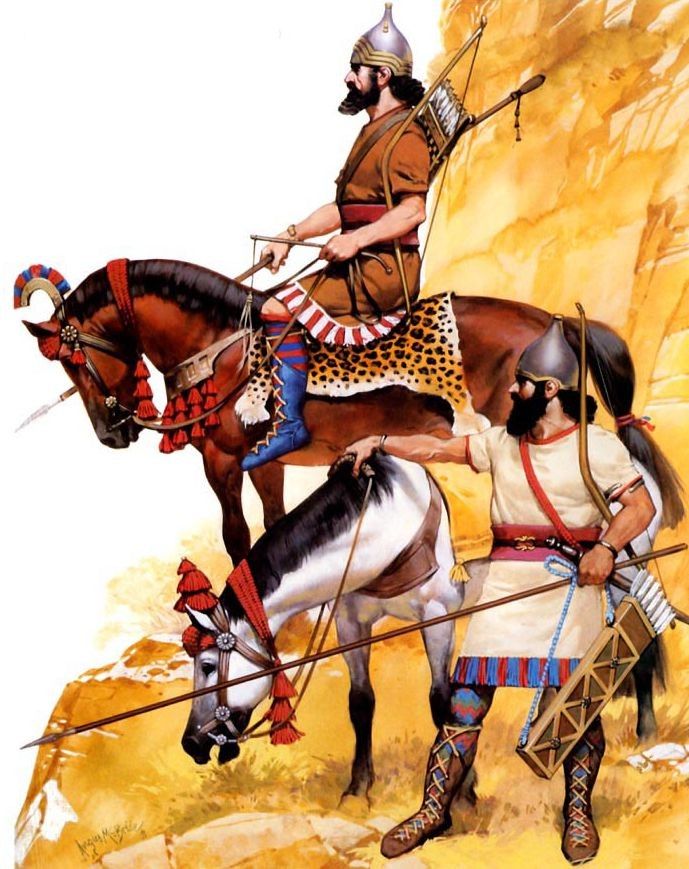

Assyrian bas-reliefs from the mid-8h century BCE onward (contemporary with the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III and his later successors such as Sennacherib) also display significant changes to the armor of cavalry and charioteers (Dezső 2012, p.256, 260-261). This generation of Assyrian cavalrymen are seen with sleeve-less scale cuirasses (covering the torso up to the waist arca), iron conical helmets (Healy 1991, 15, 61) and fighting with spears and lances.By the time of Sennacherib the Assyrian army had become a highly professional force efficiently combining its infantry, chariot and cavalry forces in a combined arms fashion (Gat 2008, 354). The southwest palace of Sennacherib displays battle scenes between cavalrymen (notably Room I, slab 20) depicting large numbers of Iranian cavalry lancers (without helmets or armor) supported by chariots (Dezső 2012, 34). Another battle scene depicts Sennacherib’s cavalry in pursuit of Mede lancers. Assyrian cavalry are now seen fighting in the nomadic style, controlling their horses independently and engaged in combat (horse archery, deploying spears/lances, etc.). The method of combat by the Assyrian cavalry spearmen (holding the spear over the shoulder) as displayed in slab 12, room VII of Sennacherib’s palace (Nadali 2010, 148) may be an indication that these were infantry spearman retrained to fight on horseback against the Mede cavalry (Eadie 1967, 161).Just five years after the onset of his reign Sennacherib attacked the Elamites. in 700 BCE capturing a number of Elamite cites. The Elamite king Halludish-In-shushinak II (r. 699-693 BCE) however struck back in 694 BCE by launching an attack into Babylon and capturing Sennacherib’s son.

Sennacherib retaliated successfully by defeating the combined Elamite-Babylonian army in 693 BCE. Then in 692 BCE, Babylon allied with Elam as well as the Parsuash (Persians). The Iranian military element (notably the cavalry and chariots) was the nucle-us of the Elamite-Babylonian army. The hard-fought battle, joined near modern-day Samarra, proved inconelusive with the Assyrians failing to achieve vie-tory with the allied armies also having suffered heavy losses (Dandamacv and Lukonin 1989, 48). Two years later in 689 BCE Sennacherib succeeded in cap-turing Babylon.These Assyrian military distractions in southwest Iran and Babylon allowed the Medes to continue consolidating their strength. Much like the previous campaigns of Sargon II and Tiglath-Pileser III, Sennacherib proved ultimately unsuccessful in subduing the Iranian cavalry.

Nevertheless while nomadic Iranian cavalry were adept in equestrian warfare, these lacked the organizational prowess and professional nature of their Assyrian adversaries. Put simply, there was not, at this time, a unified Iranian military with distinct units of fighting arms capable of operating in a coordinated fashion. A critical weakness was that many of the Iranian tribes had yet to politically unify into a single kingdom, despite the original efforts of Deioces. Lack of political unity translated into military weakness which was du-ly exploited by the Assyrians.While the Assyrians had already equipped their cavalry with older scale armor technology in their battles against the Medes (Eadie 1967, 161), a new develop-ment by the 7th century BCE was the use of lamellar armor (rectangular metal strips woven onto a fabric or leather base) by Assyrian cavalry as well regular infantry, slingers and foot archers (Healy 1991, 21-23). Mede and Assyrian horses of the 7th century BCE are also seen wearing breastplates (Winter 1980, p.4) with the Assyrians also using a type of thick fabric for protecting the torsos of their horses (Anderson 2016, 6). Lamellar armor technology was well known in Iran prior to the Mede and Persian arrivals. A key example of this is the find at the 14th century BCE Elamite site of Choqa Zanbil in southwest Iran (Dezső 2004, 320). Also existent in Iran from the second millennium BCE (prior to the Mede and Persian arrivals) was scale armor technology (Robinson 1975, 153).

Nevertheless, despite the existence of scale and lamellar technology in Iran, these types of armor were very costly for the Medes and Persians to produce on a massive scale in order to equip large bodies of troops. This resulted in such types of armor being mainly confined to the Iranian warrior elites (Gat 2008, 186). In contrast, the Assyrians, thanks to their sophisticated and efficiently organized state apparatus and economy, were evidently capable of equipping large numbers of their troops, especially cavalry, with scale and lamellar armor. Nevertheless, the Assyrian military was not be based on its cavalry arms like the future Iranian armies of the Parthians (c. 250 BCE-224 CE) and Sassanians (224-651 BCE).

From phraortes to the scythian invasions of the near and middle east

Following the end of Deioces’ rule by the Assyrians, the Mede king was suc-ceeded by his son Phraortes (r. 647-625) who was a vassal under Assyrian king Essarhadon (r. 681 669 BCE) and his successor Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 ВСЕ). Phraortes launched an offensive the Assyrians but was defeated by Ashurbani pal with Phraortes himself killed in battle (possibly during the siege of Nineveh) in 625 BCE. This led to renewed Assyrian military campaigns against the Medes as well as the Persians. Interestingly by the time of Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE) the lighter 2-man battle chariots had been apparently phased out of the Assyrian army in favor of heavier vehicles manned by three and/or four-man crews (Anderson 2016, 5). Assurbanipal’s palace reliefs illustrate larger eight-spoked wheeled chariots, with the entire crew equipped with armor. Excepting the driver, the rest of the crew are armed with swords, shields and archery (Dezső 2016, 145). Cavalry continue to be featured in Assurbanipal’s north Palace at Nineveh (Nadali 2010, 152).

The hard-pressed Medes also had to contend with another formidable foe: invading Iranian-speaking Scythians (now predominant in the northern Caucasus and Ukraine regions) who were linguistically and culturally kindred to the Persians and Medes (Channon and Hudson 1995, 18). The original impulse leading to these developments was the earlier Scythian expansion into the Crimea and southern Ukraine regions resulting in the elimination of its resident Cimmerian population(5). Those Cimmerians who survived fled southwards into the Caucasus, where they confronted and defeated the Urartian kingdom sometime in 710 BCE. A portion of the Seythians engaged in hostile pursuit of the Cimmerians who fled into the Near East, finally settling in Anatolia’s Phrygian and Cappadocian regions. As the Scythians reached the southern Caucasus by the late 6th/early 7th centuries BCE, they invaded through Urartu as evidenced by the excavation of Scythian bronze arrowheads from Armenia’s (Urartian) palace of Karımir Blur.The Scythians then attacked northwest Iran’s Manna and Lake Urmia regions, reaching the Assyrian marches by circa 650s BCE.

The Scythian arrivals into north-west Iran appear to have coincided with the rule of Phraortes’ successor Cyaxares (г. 625 585 ВСЕ). King Išpakaia of the invading Scythians soon allied with the Mannaeans which led to Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 680-669 BCE) launching military attacks into northwest Iran. Achieving success by c. 679-677 BCE, Esarhaddon defeated Išpakaia’s Scythian-Mannaean army, to then campaign into Iran with Assyrian armies once again reaching Mount Bikni (Heidel 1956, 9-37). With these military successes, Esarhaddon’s diplomacy resulted in a military alliance with the new Scythian king Bartatua (who had succeeded Išpakaia) (Frye, 1984, pp.70-72). This proved to be of utility as the Medes led by Cyaxares soon launched a successful attack into the Assyrian empire sometime in 644 BCE, thrusting all the way to Nineveh which was besieged (Anderson 2016, 8). The Scythians led by Madyas (Bartatua’s successor) came to the military aid of the Assyrians by attacking and defeating the Medes(6). Classical sources variously report the dominance of the Scythians over the Medes as having lasted as long as 28 years(7) or at just 8 years(8). In the meantime, Scythian raiders had reached as far as Egypt and ancient Israel by the 630s BCE.

It is generally agreed that Scythian dominance in Iran was overthrown by Cyaxares with Herodotus narrating that the latter had Scythian no-blemen slain during a banquet(9). Contemporary scholarship describes Cyaxares as having rebuilt the Mede army with which he re-asserted Mede authority to overthrow the Scythians to then (re)conquer the Persians (Middleton 2015, 595). While it is believed that many of the Scythians returned to eastern Europe, a significant number remained in Iran under Mede rule.

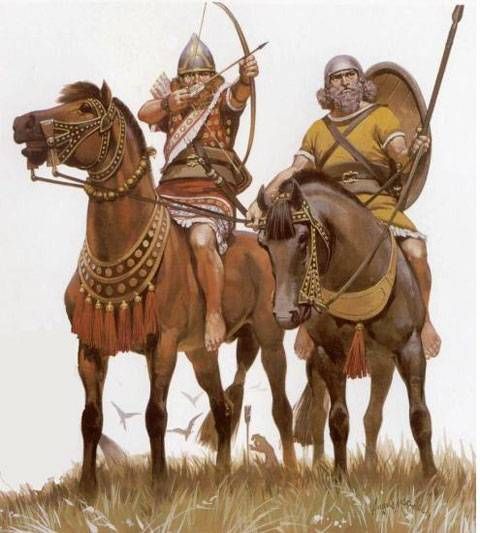

Despite fighting predominantly (like the Medes and Persians) as lightly-armored cavalry the Scythians improved the construction of scale armor. This was done by overlapping the seales (which were bound onto the leather (or cloth) vest) in a fish pattern. The overlapping scales in turn protected the lappets against spear and sword strikes (Cernenko 1989, 7). This new technology was to spread west-wards from the Scythian homelands into mainland Europe. Another Scythian innovation was the application of their new scale armor technology upon belts, shields, helmets and thigh-leg guards (Anderson 2016, 8). Archaeological excavations also reveal that this new type of cavalry, like the Medes and Persians, was also armed with a plethora of close-quarter combat weaponry such as daggers, swords, spears, javelins, maces, axes and even slings for longer range targets (Scholtz 2012, 82). The main drawback with this type of cavalry was the expense in producing these new types of armors on a large scale, thus confining these types of formations to limited numbers of prosperous elites. The develop-ment of new military technologies (notably fish-scale armor) and more heavily armed and armored cavalry were not confined to the Scythians as parallel developments were also to take place among Iranian-speaking peoples in Central Asia (Anderson 2016, 12-13). The general consensus is that the period of Scythian domination in Iran significantly influenced the development of cavalry war-fare among the Medes and the Persians (Nefedkin 2006, 6). It was these developments that were to continually evolve in the later armies of the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanian dynasties of Iran.

Rise of the mede military, obsolescence of the chariot and downfall of assyria

The first critical military reforms for the armies of the Medes are believed to have been implemented by Cyaxares during the latter part of the 7th and early 6th centuries BCE. It may be safely surmised that the principal motivation for these8 Pompeius Trogus, Justinus: Epitome of Pompeius Trogus, II, 5.1-7.9 Histories, 1, 106; IV, 12.KAVEH FARROKH Military Interactions between the Neo-Assyrian Army and Ancient…155.military reforms were the longstanding battle experiences of the Medes against Assyria’s methodically organized armies. Cyaxares now applied an effective or-ganization upon the Mede military, clearly dividing the troops into distinct corps of Rsika (spearmen), Pasti (infantry), θαnuvaniya (archers), Asabari (cavalry or “horse bearers”) and a single siege warfare battalion (Diakonoff 1956, 136)(10).

Cyaxares had finally addressed two primary weakness of the Mede armies: (1) lack of organization and (2) separate bodies of troops (e.g. cavalry, spearmen, etc.) fighting as one disorganized body. Speidel has argued that prior to these reforms the Me-des had often engaged in Beserker-style warfare in which the Medes would battle fiercely but in a disorganized fashion against the wellorganized armies of the Assyrians (2002, 257, 270, 277).The enhancement of Iranian military effectiveness as a result of Cyaxares’ or-ganization of the Mede army and advances in cavalry warfare was concomitant with the decline of the chariot as a battlefield weapon by the 7-6th centuries BCE.

As noted by Diakonoff, the Asabari (Mede cavalry) had become a highly effective battle arm as a result of Cyaxares’ reforms (1956, 136). In the wider military context, cavalry formations by the 7-6th centuries BCE had superior mobili-ty and tractability in battle environments as well as being less costly to maintain than chariots. As observed by Kradin, chariots had become obsolete by the late 7th century BCE (2016, 1). Iranian horse archery at the time of Cyaxares had also become more effective against the Assyrians. Xenophon notes that Mede horse archers were now pressing their attacks with a high level of effectiveness against the Assyrian cavalry, engaging in their pursuit and inflicting heavy casualties up-on them(11)”. This may be an indication that the Medes had now also introduced newer and more effective battle tactics, a process (at least in part) due to Scythian influence. It was with this enhanced army that Cyaxares formed his military alliance with the Neo-Babylonian king, Nabopolassar (r. c.626-605 BCE) which effectively destroyed the Assyrian Empire in 616-609 BCE. The Scythians who had remained behind in Iran after the reassertion of Mede authority, also provided their contingents in support of the Cyaxares-Nabopolassar alliance during the siege and capture of Nineveh in 612 BCE.

With the destruction of the Assyrian army, Cyaxares proceeded to expand the Mede kingdom into history’s first Irani-an empire which soon encompassed a large landmass stretching from the marches of Babylon in Mesopotamia and the borders of Lydia in Anatolia to eastern Iran facing Central Asia.

Notes:

4 Herodotus, Histories, I, 103-104

5 Herodotus, Histories, I, 102-104.

6 Herodotus, Histories, I, 103-106, 130; IV, 1-4, 12.

7 Herodotus, Histories, 1, 103-106, 130; IV, 1-4, 12.

8 Pompeius Trogus, Justinus: Epitome of Pompeius Trogus, II. 5.1-7.

9 Histories, 1, 106; IV, 12.

10 Herodotus, Histories, 1, 103.

11 Cyropedia, 1, 4.23-24.

Bibliography:

Autore: Kaveh Farrokh

Fonte: History of Antique Arms

Categorie:

Tags:

Lascia un commento