Abstract: Broken treaties, mutual aid agreements, imperial expansion, and the thirst for economic expansion all come to mind when thinking about the great world wars of 1914 and 1941, but they, in fact, occurred 158 years before. The great imperial powers of the day mustered great armies, deployed strong fleets, and hired mercenaries to prosecute their objectives from the humidity of far-off India to the heat of Africa and the sprawling forests of North America. The Seven Year’s War would see all of the facets of a global war come to bear in the struggle for supremacy and thus effectively become World War Zero.

The wide-ranging conflagration now known as the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) saw combatants from nearly a dozen nations or confederations engage in hostilities spread over five continents and numerous oceans and seas. Often cited by historians as the first truly global war in which belligerent nations poured the entirety of their countries’ resources into the conflict, the war saw the major powers of the day lead the way into the fog of war. The Seven Years’ War would see the primary nations of Great Britain, France, Prussia, and Austria engage in a war that would span the globe, irrevocably change their societies, and establish its place in the pantheon of military history for its far-reaching consequences.

Origins of the Seven Years’ War

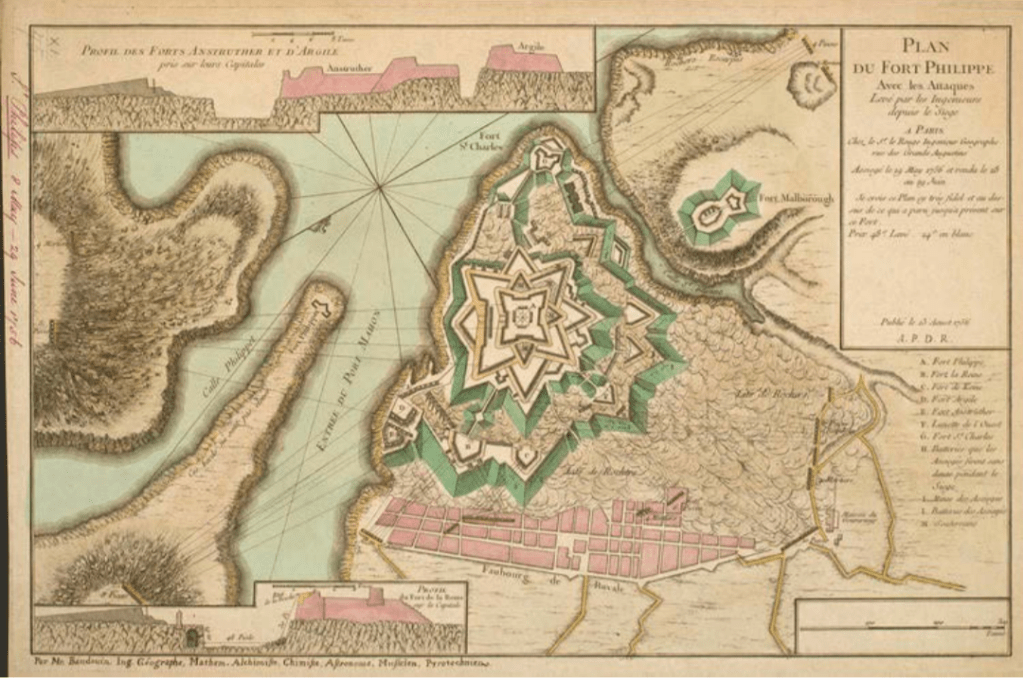

As is the case with many conflicts, the origins of the Seven Years’ War can be traced back to an earlier conflict whose treaty did little to address the under-lying resentments that festered. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle in 1748, also known as the Treaty of Aachen, ended the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748) that was centered around Maria Theresa’s (1717–1780) ascension to the Austrian throne. The treaty effectively returned things to the way they were before the fighting started but subsequently did not address the grievances and underlying animosities, such as Austria recognizing (but not accepting) Prussia’s conquest of Silesia from the first two Silesian Wars (1740–1742 and 1744–1745) and its sovereign, Frederick II’s (1712–1786) growing military power. It also involved simmering hostilities over North American territory and resources. Imperial power, prestige, and economic well-being were at stake, and while the nations did not actively seek another war, they did little to assuage one. The Seven Years’ War outbreak was not the direct result of one inci-dent, but rather of two that lead to official declarations of war. Firstly, Anglo-French colonial rivalry came to a head in 1756. That year in North America, the French—under the Marquis Louis Joseph de Montcalm (1712–1759)—arrived with reinforcements of over 1,000 troops and six ships of the line to bolster their military presence, which they used to attack and destroy the British fort at Oswego in New York.(1) North America was the disputed prize for both countries, and both sought to dominate and claim its bountiful resources.The formal declaration of war between France and Britain came because of a French invasion of the small Mediterranean island of Minorca in April 1756. Here the British had established a major naval port at Port Mahon, with 2,000 troops on the island and dozens of ships patrolling between Minorca and Gibraltar.

(This map depicts French siege plans for Fort St. Philips, Minorca, 8 May-29 June 1756 at Port Mahon during the Seven Years’ War. Etching and engraving; printed on paper; hand-coloured | Scale: 1:2,950 approx. Royal Collection Trust #RCIN 731075. https://militarymaps.rct.uk/the-seven-years-war-1756-63/st-philips-1756-plan-du-fort-philippe-avec-les).

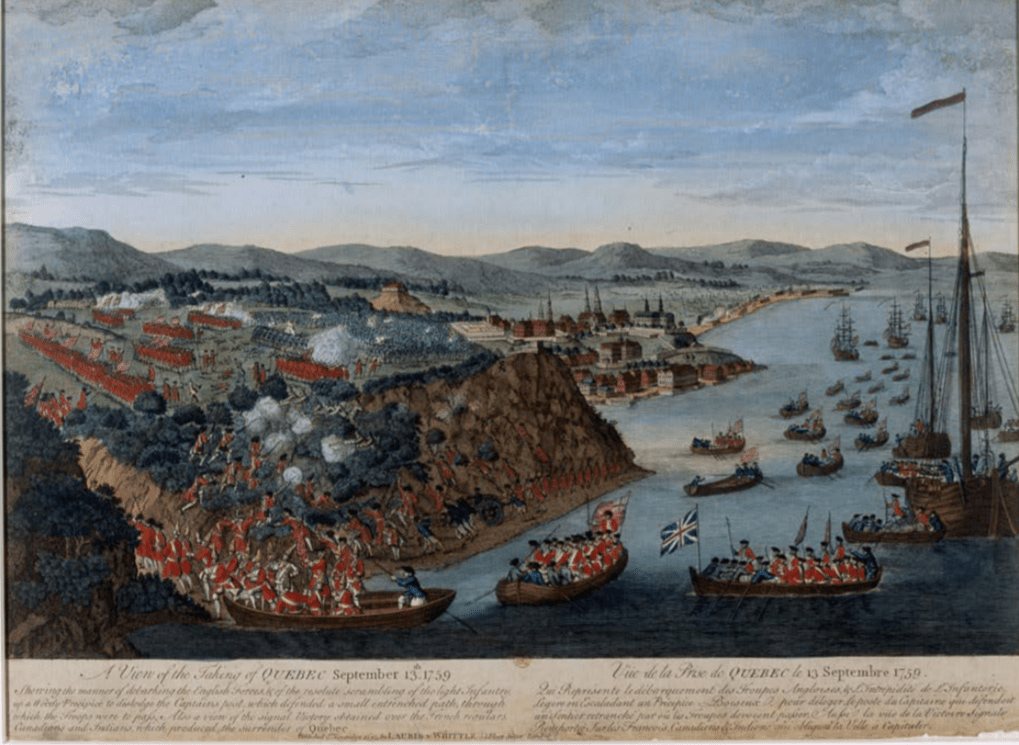

(The taking of French-controlled Quebec on 13 September 1759 by British General James Wolfe would be the death knell for the French domination of North America. Though a pyrrhic with Wolfe having been mortally wounded during the battle, the British would effectively control most of North America. National Army Museum, London, UK).

A French invasion force of 12 ships and 15,000 soldiers landed on the island in April and, by May 1756, had begun firing on the British and their defensive positions at Port Mahon.(2) News of the invasion made its way to the politicians in London, who refused to stand idly by declaring war on France on 17 May 1756. In less than two weeks, on 28 May, after a failed naval engagement to break the siege, the British surrendered the island to the French. The powder keg had exploded. The second impetus was on the European continent; Frederick II and Prussia took the initiative and pushed into Saxony to beat the Austrians to the punch. Having heard reports for months of an Austrian buildup, as well as a possible offensive alliance with Russia to attack Prussia, Frederick pre-emptively launched his army in August of 1756. Facing a grand alliance of Austria, France, and Russia, Frederick felt that the three had conspired against him and therefore felt justified, for the sake of Prussia’s very survival, in striking first. Frederick said that:

Hostilities should not be confused with aggression. The one who makes the first plan to attack his neighbor breaks the engagements that he has undertaken for the peace, he plots, he conspires; this is in what true aggression consists. The one who has learned of it and who does not take the initiative is a coward; the one who foresees [the plan of] his enemy commits the first hostilities, but he is not the aggressor(3).

Leading his Prussian army of 29,000 into Saxony, Frederick hammered the Saxon army into submission on 17 October 1756, while simultaneously beating back an Austrian relief army of over 40,000 under Marshall Maximilian Ulysses von Browne (1705–1757). Prussia was now engaged in a war of survival on the continent, and her only ally, Great Britain, was focused on France and her contest for colonial possessions and could offer no effective military support. However, Britain’s king, George III (1738–1820), realized the importance of securing their continental territory of Hanover and therefore provided Prussia with financial support in the hundreds of thousands of pounds and material support. George knew that if Hanover was lost to France or its allies, Britain would be forced to return any seized territories in future negotiations in exchange for it, so Prussia’s war on the continent served his own purpose in beating back.

France and the others and by extension, protecting Britain’s interests. The European continent was now engulfed in its next conflict—the European theater of the Seven Years’ War. The reach and influence of the key belligerents stretched beyond just that of the Americas and Europe. In fact, the hostilities would extend far to the east into India, where a proxy war within a proxy war would break out as part of the contest of empires between Great Britain and France. India was never a theater of direct focus, so it would never garner the amount of attention or resources that were seen in North America or Europe. Still, this extension of the Seven Years’ War was one founded on the commercial interests of both the English and the French. Though as of 1754, the totality of English trade imports from the Orient (including India) amounted to only 6% and exports of 13%, as compared to 30% and 40% respectively, from the Western Hemisphere, India was still an important colonial holding with huge commercial potential that both Great Britain and France would not give up easily.(4) The establishment of trade posts and trade colonies in the sixteenth cen-tury by the Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French gave Europeans a foothold in India. By the eighteenth century, Great Britain and France were the effective commercial powers in India, whose influences were exerted through their respective East India Company. Of the two, the English East India Company was far and away the most viable and solvent, having applied a dynamic approach to financial capitalization that allowed them to produce trade that was nearly four times higher than their French counterparts while keeping their shipping and military costs below those of the French as well.(5) By the time word of hostilities between their host countries had reached the Indian subcontinent in 1756, the various East Indian Companies had already been engaged in fight-ing in one fashion or another, as proxies in a struggle between Indian princes for control of various territories. This new round of fighting “officially” allowed the French and British to actively engage each other’s trade in the Indian Ocean as well as their respective settlements, which included those in Carnatic, Awdh, Deccan, and Bengal, as “the land revenue was vital to the companies and the princes to meet the immediate costs of prosecuting the Seven Years’ War in India.”(6)The Indian Theater saw the French and their proxy forces under Governor-General Joseph Dupleix (1697–1763) face off with his English rival and Governor of Calcutta, Robert Clive (1725–1774). It was during this period that saw the infamous event, the Black Hole of Calcutta, occur when the French-backed Siraj-ud-daula (1733–1757) captured and imprisoned up to 60 English traders in the cramped confines of Fort William, where as many as 40 perished from heat exhaustion. The English under Clive and the English East India Company exacted their revenge and the beginning of their dominance in India with their victory at Plassey on 23 June 1757.

The British East India Company and, by default, Great Britain had effectively defeated the French and established political, military, and economic control over India by 1761. The impetus in India for the fighting and strife was once again a matter of commercial interests and how the revenues from India would help finance their hosts efforts in larger domains. The successful conflict in India was so impactful for the British that historian Brooks Adams (1848–1927) said: “Possibly since the world began, no investment has ever yielded the profit reaped from the Indian plunder, because for nearly fifty years Great Britain stood without a competitor.”(7)

The diplomatic failures by both the British and the French certainly fired the blood of their respective war hawks, but at its core, the entire conflict blew up out of a colonial Game of Thrones for the possession of North America. The British, French, and their Native allies and proxies engaged over three disputed areas: Acadia-Nova Scotia, the boundaries between Canada, New York, and New England, and the important Ohio River Valley.(8) In this North American theater, the two colonial superpowers took a slow-burn approach to the coming conflict, initially paying the continent relatively no mind. In all three of the contested areas, there had been acceptable incursions and minor conflicts by both sides. Ever-escalating and more serious provocations by both parties had sent them both on the path to formal outright war by 1754. The call for outright action is summed up in a correspondence between the English crown and the governor of Massachusetts, William Shirley (1694–1771), over French incursions, in which he states, “His majesty extremely approves the Resolution which has been taken by the Assembly of your province in Consequence of the Proposal recommended by you to drive the French from the River Kennebec [modern Maine].”(9) Colonial brinksmanship, territorial peril, commercial interests, and at its heart, control of North America were all underlying root causes for conflict that spanned ocean to ocean, east to west.

Ramifications of World War Zero

The fallout and consequences of what were effectively three wars—the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the Third Carnatic War (1756–1763), and the Third Silesian War (1756–1763)—all under the umbrella of the Seven Years’ War, were both immediate and lasting. In the immediate sense, the scale of the death toll was enormous. Record-keeping was sporadic or nearly nonexistent at the time, with muster rolls and military accounting being the closest semblance of such data that could be gleaned. This fails to consider the greatest loss of life—suffered by the civilian populations, from the indigenous Native Americas in the Western Hemisphere to the simple farmers of Prussia and Saxony to the tribal people of India. Some estimates place total civilian causalities from all the collective fighting from America, Europe, and India at nearly 1.5 million deaths, with—ironically—military deaths being a collective fraction of this.

The loss level is best stated with Prussia, who at the beginning of the Seven Years’ War had a population of 4.5 million but by its end in 1763, saw that drop by 500,000, as 11 percent of its citizens had died in the war.(10) These deaths resulted from various factors, from direct military action to starvation. Still, the largest proportions can be attributed to disease, which also took the lives of more soldiers at the time than combat did. Prussia’s rival for context, Austria, suffered an even larger loss of population, as by war’s end, its population dropped by one million citizens or roughly 15 percent of its population, from nearly six million in 1754. The financial costs of conducting and waging a total war over vast distances proved nearly fatal and catastrophic to all involved. Britain’s national debt doubled to £133 million, which put them near bankruptcy by year’s end, as the total tax revenue in 1756 was no more than £30 million.(11) Their fiscal dire straits forced them to make dramatic cuts to their 100-plus regiments, ranging from disbanding many units to putting others only halfway for an indefinite period. It took decades before Britain recovered and rebuilt its army.The situation was even worse in France, where King Louis XV (1710–1774) faced near insolvency. French finances were so affected and with no credit being granted, that the king was forced to reduce the proud French army to no more than 100,000, effectively making them the national guard of France with no funding for conducting offensive operations, let alone fight another war. The depressed financial situation in Austria forced Maria Theresa to borrow tens of millions of pounds to stay afloat while the Swedish government and its finances collapsed. Ironically, the financial survivors proved to be Prussia and Russia. Frederick II utilized a combination of currency manipulation, increased taxes, and war plundering to effectively pay for his war efforts, even after spending over £31 million defending his Silesian conquest from Austria.(12) Russia’s weathering of the economic tsunami from the Seven Years’ War can be attributed to her short time participating in it. The ascension of Czar Peter III (1728–1762) to the throne of Russia upon the death of Czarina Elizabeth (b. 1709) in January of 1762 proved fortuitous for both Russia and Prussia; pro-Prussian Peter denounced their previous treaty with Austria and agreed to leave Prussian lands as part of the Prussian-Russo Treaty of St. Petersburg on 5 March 1762.(13) The lasting effects of the Seven Years’ War cannot be understated, as it was directly responsible for the coming American Revolution that up-ended the entire world. The massive cost of fighting such a global war had nearly emptied the coffers of Great Britain, so King George III (1738–1820) decided to use his newly won colonies in North America as a source of revenue. It was from this basis of the North American colonies being used as nothing more than an early ATM of sorts for the British crown, along with escalating taxation and general indifference to its citizens, that would lead to the outright revolution in 1775. This effectively changed the course of the world.In French society, the burden of increased taxes, combined with substantial battlefield and colonial losses, created an environment ripe for change. This came to a head with the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, when oppressive taxes to rebuild the military from the Seven Years’ War, combined with needed military and governmen-tal reforms, backed by civil rights, encouraged France to reinvent itself and rise once again to martial glory under the auspices of a man from Corsica who became France’s first emperor.Prussia, under Frederick, emerged from the war as a dominant player in Europe and became the dominant German state within the next 100 years. Prussian military success and prestige changed Prussian society by elevating it from a backward out-of-touch society to one of dominance and respect. This was further cemented in the supreme power that the soldier-king Frederick espoused when he said, “The sovereign is the foremost judge, general, financier, and minister of his country, not merely for the sake of his prestige.”(14) His leadership further changed Prussian society and became the hallmark of future German leaders.

The Seven Years’ War Place in the Context of Military History

The Seven Years’ War has a unique and ubiquitous position in military history for two distinct reasons—the first is regarding the nature and scope of the war itself, and the second is that of its ending through a series of treaties and their long-term consequences.The Seven Years’ War was the first true world war, vast in scale—encompassing multiple continents, differ-ent hemispheres, almost a dozen belligerent parties, naval engagements, and proxy wars. The totality of the conduct of the war—from the sacrifices of its citizens to focus on the militarization of society, to the putting to sea of large contingents of naval assets for trade protection and military engagement as with the British, to massed Austrian conscriptions to field large armies for offensive operations—all occurred on a scale not seen before in human conflict. Diverse facets of the war played out in the widest geographical terms, from the heavy forests of North America, naval engagements in the Mediterranean Sea, urban warfare, and massed armies in continental Europe to the proxy armies of the various East India Company and their supporting Indian native troops. No other conflict in history up to that point had ranged so far and wide. When placed in the context of total war that each of the participating nations had invested themselves in, it also set a precedence as to the collective human, material, and economic devastation. Colonial interests, shifting alliances, professional and auxiliary armies, and native contingents of troops, in conjunction with widespread naval engagements, spread and carried the fighting throughout the colonies of the main powers, often dragging others in, affecting more societies in the process. The collective human toll, both military and civilian, was on a scale not seen or experienced before this, ranging well over one million casualties, which by this fact alone, warrants it a place in the halls of military history.The long-term consequences of the ending of the war are the second and most lasting impact of the Seven Years’ War. The war came to an effective end, not with the signing of one treaty, though the Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended fighting between the two largest parties of Great Britain and France, but rather with four treaties. These in to-tal, include St. Petersburg, Hamburg, Paris, and Hubertusburg (five if you include the Treaty of Long Island-on-the-Holston in 1761, which ended the Anglo-Cherokee conflict).(15) The treaties saw France ceding territory and colonial possessions from Canada, east of the Mississippi, to India, thus turning Great Britain into the first real-world superpower. Backed by her dominance of the oceans, thanks to the power of the Royal Navy, she was unmatched in naval supremacy—this strength continued into the twentieth century. These new colonial possessions became the breeding ground for American independence, while France’s failures on the battlefield precipitated a coming revolution that changed the future of Europe. The most far-reaching consequence of the Seven Years’ War was the survival, establishment, and growth of the five major powers that came out of it—Great Britain, France, Prussia, Austria, and Russia. These countries went on to control the power structures of the Eurocentric world, which came to a head with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The consequences of the Seven Years’ War changed the dynamic in Europe at the time with its enormous toll on lives lost, financial destruction, and the scale of military operations. More importantly, it sowed the seeds of revolution in America and France that changed the world. Prussia’s success in the war gave rise to her military dominance and monopoly as the key German state within 100 years while also setting up the groundwork for two world wars that eclipsed the carnage wrought by the Seven Years’ War in every possible fashion. The Seven Years’ War has a rightful place in military history as the first truly global war that spanned much of the known world, disrupted, and changed societies from one hemisphere to another, while its very ending set up sequences of events that profoundly changed not only countries but the entire world.

Notes:

1 Daniel Marston, The Seven Years’ War (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2001), 26.

2 Ibid., 26.

3 Robert B. Asprey, Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma (New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields, 1986), 425.

4 Mark H. Danley and Patrick J. Speelman, The Seven Years’ War: Global Views (Leiden: BRILL, 2012), 73, ProQuest Ebook Central.

5 Ibid., 73-74.

6 Ibid., 76.

7 J F C Fuller, A Military History of the Western World, vol. II (New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1987), 242.

8 Higonnet, Patrice Louis-René. “The Origins of the Seven Years’ War.” The Journal of Modern History 40, no. 1 (1968): 58.

9 Ibid., 59.

10 Robert B. Asprey, Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma (New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields, 1986), 563.

11 Daniel Marston, The Seven Years’ War (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2001), 83.

12 Mark H. Danley and Patrick J. Speelman, The Seven Years’ War: Global Views (Leiden: BRILL, 2012), 527, ProQuest Ebook Central.

13 Ibid., 520.

14 Frederick II, “Frederick II: Essay on Forms of Government,” trans. J. Ellis Barker, Ford-ham University, accessed February 16, 2022, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/18fred2.asp.

15 Mark H. Danley and Patrick J. Speelman, The Seven Years’ War: Global Views (Leiden: BRILL, 2012), 519, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources

Asprey, Robert B. Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma. New York, NY:

Ticknor & Fields, 1986.

Fuller, J F C. A Military History of the Western World Vol. II. New York, NY: Da

Capo Press, 1987.

Danley, Mark H., and Patrick J. Speelman. The Seven Years’ War: Global Views.

Leiden: BRILL, 2012. Accessed February 16, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Marston, Daniel. The Seven Years’ War. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2001.

Autore: Michael G. Stroud

Fonte: militaryhistorychronicles.org

Categorie: Moderna Strategia e Dottrina Campagne Battaglie

Tag: Art of war Military History Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) Military Thinking Military Analysis

Lascia un commento