ABSTRACT:

At the height of the Thirty Years War, news from South America, West Africa and the Caribbean was widespread and quickly distributed in the central European peripheries of the early modern Atlantic world. Despite the German retreat from sixteenth-century colonial experiments, overseas reports sometimes appeared in remote southern German towns before they were printed in Spain or the Low Countries. This article explains the vivid German interest in Atlantic news and examines how correspondents designed their overseas reports for a specifically German news market by connecting them to the European political and military situation, using a rhetorical frame of global conflict. While the domestic importance of American news was sometimes overstated by German newsmakers, its dissemination helps us understand how a sense of global connectedness emerged in a new print genre and created a discourse that supported the spatial and temporal integration of events around the globe.

The temporal and geographical boundaries of the Thirty Years War as a historiographical unit have been critically discussed and re-examined since mid-twentieth-century scholarship argued that this conflict was ‘never exclusively, or even primarily, a German affair but concerned the whole of Europe’.[1] While the wider European significance of the war has since then been fully acknowledged, historians have only recently started to situate it in a global context by integrating its various Atlantic side stages more systematically into their analyses.[2]

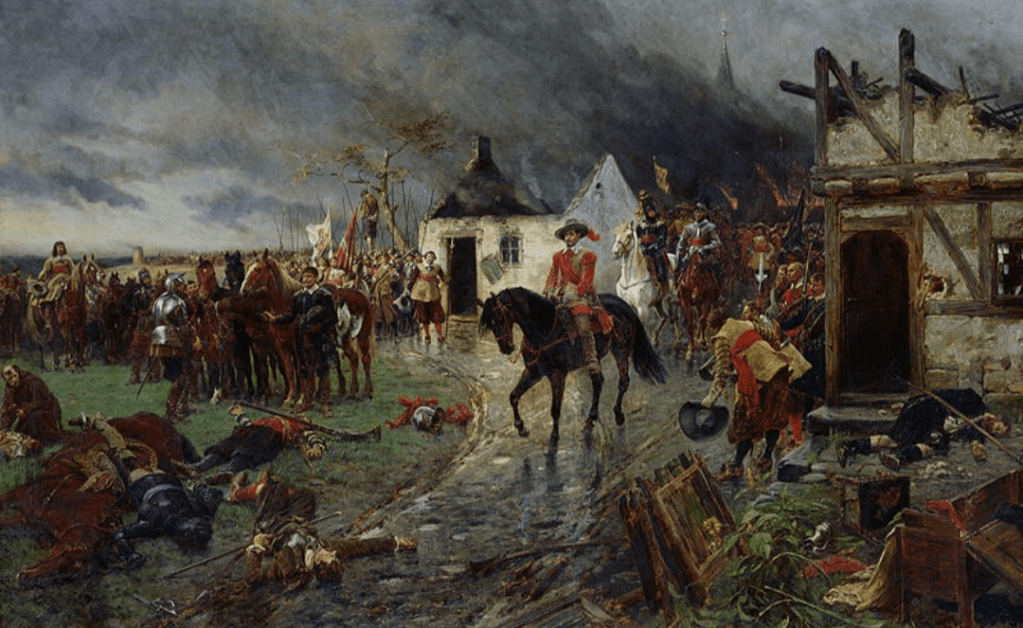

For contemporaries the global dimension of the Thirty Years War was a far less outlandish idea than for historians who later reconstructed and narrated its events in predominantly national frameworks. In the early 1640s, Volkmar Happe, chronicler and counsellor at the small court of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen in Thuringia, looked back at the events that ‘led to the bloody Bohemian War that lasted continually for many years, crawling through virtually the entire world and devastating all the lands’.[3] Like other chroniclers of his time, but in retrospect, Happe also mentioned the famous comet that appeared between November 1618 and early 1619 and foreshadowed ‘war, uproar, bloodshed, pestilence and dearth in all the world’.[4] While the phrase ‘all the world’ might also be understood in a metonymical sense, ‘crawling through virtually the entire world’ is at least an indirect allusion to geographical reality. Happe’s chronicle was not the only one that widely expanded the scope of the Thirty Years War and situated it in a world-historical setting. In a similar yet more tabular fashion, other manuscript chronicles such as the Diarium belli Bohemici by Ratzeburg cathedral canon Otto von Estorf or the diaries of Christian II of Anhalt-Bernburg documented the ‘Bohemian war’ by extensively referring to overseas events such as local revolts in Mexico, Dutch attacks on Portuguese Brazil and the arrival of Peruvian silver in Seville. In December 1628, Christian II dedicated no fewer than six pages to the Dutch capture of the Spanish treasure fleet in Cuba and commented on the possible impact of this event on the payment of troops in Europe.[5]

Read in the context of seventeenth-century German news culture, such perceptions of the Thirty Years War’s assumed global dimension seem less idiosyncratic than later historiographical definitions of this conflict suggest, and—at least in Estorf’s case—it is evident that periodical news media were among the sources of such chronicles. Newspapers, bi-annual news compilations and pamphlets that reported on recent military campaigns and political negotiations categorized these events according to ordering patterns different from those of later historiography. Contemporary news media presented links, causalities and correlations between German and international events that did not find their way into canonical narratives. In the crucial years of the Thirty Years War, several German newspapers chose to report extensively on overseas events such as the struggle for Brazil, the course of the annual Spanish silver fleet or battles off the coasts of West Africa. This article examines how news correspondents and editors related these events to domestic affairs and created a vision of a global war in which the fate of Germany was decided not only in Central Europe but also in the Atlantic Ocean and, more specifically, the Americas.

Studies that situate the seventeenth-century Holy Roman Empire in a global historical context are often founded on the assumption that the Thirty Years War threw Germany back into a state of relative isolationism and cut many of its older ties to Atlantic and Asian trade networks.[6] In the second half of the sixteenth century—after the collapse of the South German merchant empires of the Welser and Fugger families—the German presence in the American Habsburg colonies was already in decline, a process that was only intensified by the political and military turmoil on the eve of the Thirty Years War.[7] Cultural and media historians have therefore long assumed that German interest in the non-European world continuously dropped, a process that seemed to be confirmed by a gradual decline of German travel writing and geographical literature, genres that had flourished in the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century German book market.[8]

Focusing on the German news market of the first half of the seventeenth century, this article argues that the retreat of Germans from the Atlantic World and the political disintegration of the Holy Roman Empire had in fact the opposite effect on interest in the world beyond continental Europe. The quantity of overseas news reports and their embeddedness in domestic contexts challenge the notion of German isolationism between the heyday of the Welser and Fugger trading houses and the Brandenburg experiments in Atlantic trade in the second half of the seventeenth century.[9] In the reports of early German newspapers, domestic problems did not simply overshadow global developments but laid the foundation for an increasing reception of overseas events. Observing the war from a horizontal perspective and lacking the temporal distance that might allow for a more comprehensive interpretation of present events, publishers turned to transoceanic news to make sense of the great conflict of their time. As their correspondence with news writers all over Europe suggests, war on the scale witnessed between 1618 and 1648 could best be understood by situating local events in the context of global developments.

To explore the emergence of such a discourse of global connectedness, this article focuses on a selection of five well-preserved newspapers from the bi-confessional towns of Öttingen and Nördlingen, from Protestant Strasbourg and Stuttgart and from the Catholic city of Munich and adds a smaller number of comparative examples from northern Germany, the Rhineland and the Low Countries[10] After a short overview of the rise of German periodical newspapers in the context of the Thirty Years War and the ways in which the interplay between news correspondents and editors could shape political messages, I will address the news reception of the Dutch struggle in Brazil, the yearly course of the Spanish silver fleet and the attempts of international trade agents to incorporate Germany into new Atlantic trade experiments. These observations allow for a re-evaluation of the position of early modern Germany’s media cultures in a global historical setting.As the presented cases show, the frequent dissemination of transoceanic news and its integration into domestic developments brought about a qualitative change in the early modern European imagination of the global. While earlier European print media such as travel reports, news pamphlets or political broadsheets also connected local and global developments and even used foreign events to make domestic political arguments, as for example in the anti-Hispanic Black Legend, they did so by presenting their objects in the marvellous and otherworldly light of a different historical and geographical order.[11] What the weekly printed newspapers added was a new discourse of connectedness that brought about a sense of synchronicity and immediacy that integrated transoceanic history both spatially and temporally.

I. THE THIRTY YEARS WAR AND THE RISE OF THE NEWSPAPER

The invention of the printed newspaper was a less spectacular media revolution than its later history might suggest, and it emerged from, and coexisted with, a number of other news media, such as handwritten newsletters and pamphlets and the bi-annual news compilations that were known as Messrelationen. The latter had been sold at the spring and autumn fairs in Frankfurt and Leipzig since the 1580s and recounted the most memorable events of the past six months.[12] In 1605, Strasbourg printer and book dealer Johann Carolus requested permission from the city council to publish his weekly news manuscripts in print. His format—a booklet of eight quarto pages—and the short indications of date and place for the reports would become the model for German newspaper throughout the seventeenth century. Even though Carolus probably did not see his new business idea as fundamentally different from earlier handwritten newspapers—except that he was able to produce faster and more cheaply—his innovation can be considered the first periodical newspaper in print.[13]

While Carolus found a substantial number of imitators between 1609 and 1618, the start of the Thirty Years War saw the rapid growth of this medium, with a wave of new weekly newspapers between 1619 and 1623. In the 1620s, some publishers started to print their papers twice a week and the Swedish entry into the war in 1630 led to a second surge in new titles. The spectacular rise of the newspaper in Germany is widely seen as a direct result of the political and military escalation and the growing demand for quick and trustworthy information about the course of the war.[14] Not only the military events themselves but also the political disintegration of the Empire and its territorial structure shaped the diverse and highly differentiated news landscapes of seventeenth-century Germany.[15] In contrast to centralizing states like England and France, where governments were able to manage the circulation of news more effectively, imperial control of the news market in the various territories was virtually non-existent.

German news publishers in the first half of the seventeenth century were not journalists in the modern sense. They relied on correspondence networks that provided them with incoming reports from all major European cities. These news reports were collected and then printed with an indication of the original date and place. Every newspaper had its own system for ordering the various reports. Southern German papers often filled their front pages with news from the Netherlands or Spain, while Hamburg publishers started with news from the southern parts of the Empire or from the Mediterranean.[16] As a result, older scholarship has taken these news sheets as rather unfiltered collections of incoming correspondence that did not add context.[17] However, their appearance as raw and unedited news compilations was part of their business model, as it suggested uncorrupted authenticity and protected them from conflicts with local magistrates or territorial rulers. The principle of relata refero, or the publication of ‘what has been related to me’, was indeed widely accepted and offered news publishers in German cities the possibility of operating without excessive government interference.[18] Publishers like Carolus were therefore eager to assure their audiences that they published their correspondence ‘without any additions and not otherwise than in the manner in which it has been written and received’.[19]

Such claims of neutrality and impartiality require some explanation. While some original reports were certainly published simply as they had been received, there is ample evidence that at least some of Germany’s early newspapers were strongly edited. As Wolfgang Behringer has demonstrated in the case of the aforementioned Carolus, even the first German newspaper did not strictly follow the relata refero-principle, and it seldom published its incoming reports without any editorial changes.[20]Other publishers, such as Johann Weyrich Rößlin or Lucas Schultes, sometimes even used the same incoming reports to fill two separate issues, even though the editorial changes were rather modest in such cases.[21] Other newspapers added specific confessional messages to their reports: one Hamburg paper consistently spelled Jesuits as ‘Jesuwider’, literally ‘antagonists of Jesus’, a Protestant sneer that had already been used in sixteenth-century anti-Catholic pamphlets.[22]

As Jörg Jochen Berns has argued, even when newsmakers published reports without any editorial changes, the apparent ‘subjectlessness’ of the publisher does not imply ‘that the newspaper he produces is itself impartial.’[23] In such cases, the reports still contained the specific perspective of a newspaper’s informants and subsequently the publisher had decided which reports to include in the printed paper. Despite their appearance as raw and sometimes inaccessible collections of dry reports, early newspapers did not offer a neutral perspective on contemporary events but often followed editorial strategies to present the news in at least rudimentary narrative structures.[24] Alongside the complex interactions between correspondents and editors all over Europe and the resulting multiperspectivity of the published newspapers, it is thus possible to detect editorial choices, for example with regard to the events and geographical regions that were covered. Thus until the second half of the seventeenth century, German newsmakers commented only reluctantly on the events they recounted, but they were already directing their readers’ attention by highlighting certain reports or connecting them to their coverage of other events.

The turn to events in the Atlantic world and their incorporation into an imagery of global warfare was one such choice, and one prevalent in southern Germany. Even when several newspapers received identical reports, some chose to highlight information about Atlantic events, for example the aforementioned Schultes and Rößlin, while Hamburg and Munich papers tended to be rather brief on these topics. Nonetheless, the focus of the news coverage remained Europe in all studied cases. Even in weeks when news about Dutch Brazil or the Spanish treasure fleet appeared on the first pages of a newspaper, the vast majority of all reports still concerned European events, and information about the Atlantic World was primarily incorporated in order to interpret and contextualize political developments at home.[25]

II. WAR IN GERMANY AND THE SOUTH ATLANTIC

Transoceanic news had travelled through the communication networks of all of western and central Europe since the sixteenth century, when it was transferred in handwritten newsletters between merchants and diplomats.[26] However, the scale of its dissemination would drastically change with the emergence of printed periodical newspapers: while even prominent news writers in sixteenth-century Germany often had no more than ten to fifteen permanent subscribers, printed newspapers typically had a circulation of several hundred copies.[27] In addition, the focus on the non-European world increased during the 1620s and 1630s. Some publishers highlighted transoceanic news in their printed newspapers: Öttingen (later Nördlingen) printer Lucas Schultes always put news from Brazil, Cuba or Mexico on the first page of his bi-weekly newspaper Continuation der Augsburger und Nürnberger Zeitung. Only in months when spectacular continental military events dominated the European news landscape, such as the sieges of Bois le Duc and Magdeburg in 1629 and 1630/31 respectively, did he turn to less distant news reports to fill his front pages. While news publishers in the Northern Netherlands had obvious reason to issue reports on the Dutch East India Company and Dutch West India Company on a regular basis, the hunger for overseas news in towns like Stuttgart, Öttingen, Nördlingen, Munich or Strasbourg was less self-evident. Yet the coverage of developments in the Atlantic world was enormous in these towns: in 1630 Schultes published no fewer than 114 reports that covered one or more Atlantic news events, and in the years before he had issued between three and four overseas reports per month. The weekly Zeittungen of Schultes’ Stuttgart colleague Rößlin included even more reports on Atlantic events. While none of Rößlin’s issues for 1628 to 1630 have survived, the amount of news from South America in the previous years is spectacular: in 1624, Rößlin published 121 news reports that referred to events in the Atlantic world—roughly 12 per cent of the entire news coverage in that year.[28] In the following years, the newspaper included respectively 103, 76 and 40 Atlantic reports, and also news from Asia.

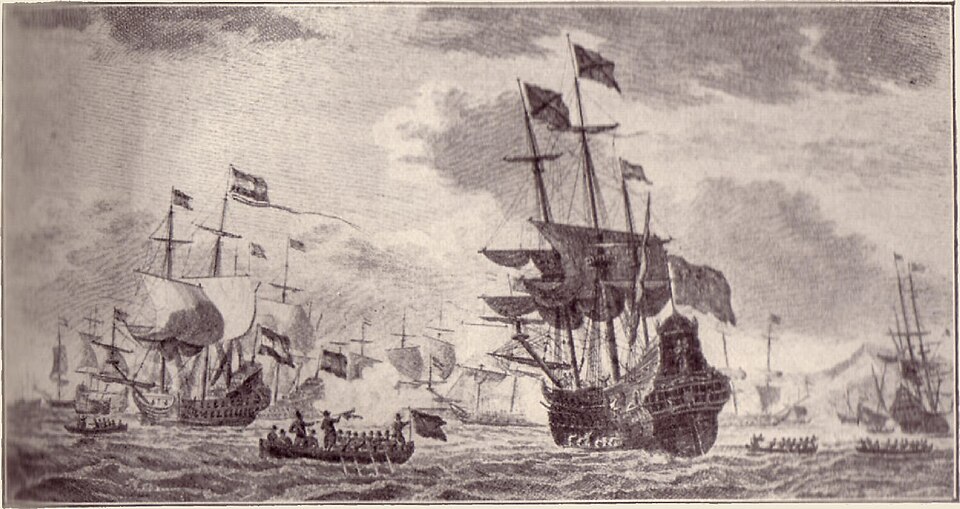

Rößlin and Schultes as well as their Catholic counterpart Adam Berg in Munich tried to bring their news from the various Atlantic regions as quickly as possible. On 24 February 1630, Schultes issued an account that described the safe arrival of the Spanish silver fleet in Cape Verde and was based on a report written in Rome on 9 February.[29] A day or two later, Berg’s Wochentliche Ordinari Zeitung brought a shorter version of this account.[30] Berg’s and Schultes’ relative proximity to the news hubs of Italy sometimes provided them with quicker access to Atlantic reports than had the seaports of the Low Countries: Antwerp saw the same reports almost three weeks later than Schultes, on 15 March.[31] A year later, in 1631, Schultes’ account of the arrival of the silver fleet, based on sources from Milan, appeared earlier than the Amsterdam reports that covered this topic. The inclination to report news from the Americas as soon as possible also had its pitfalls, and southern German newspapers were prone to reporting unfounded rumours they had received from their correspondents in Italy and the Low Countries. In 1630 Schultes and Hamburg publisher Martin Schumacher announced the Dutch conquest of Pernambuco before Dutch soldiers had even set foot on the Brazilian coast.[32] Amsterdam publishers were more careful and waited until they deemed the incoming reports credible enough for publication.[33] In this case, Schultes’ and Rößlin’s reports were primarily based on rumours and their own interpretation of the strategic context, which made a Dutch victory likely. Despite the potential unreliability of their news—Rößlin and Schultes were typically more careful than in the aforementioned examples—their hasty publication of Atlantic news reports reflects an eagerness to learn immediately about developments in these regions, especially on the South American coasts. Apparently Rößlin expected his readers to be waiting for overseas news: in 1624 he sought to explain the lack of reports, relating that pirates from Dunkirk had caught Dutch ships and thereby cut off the flow of Atlantic information to the Dutch seaports.[34]

While the annual course of the Spanish silver fleet was covered by German news media throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, information about the incoming bullion was primarily disseminated in manuscript newsletters. [35] It was only after 1624 and the Dutch assault on Bahia de Todos los Santos in Portuguese Brazil that a consistent interest in American news began to grow among wider audiences. This event was celebrated not only in the cities of the Northern Netherlands but also in the Protestant territories of the Holy Roman Empire, where it was disseminated in a wide range of media: news pamphlets, broadsheets, newspapers and in the aforementioned Messrelationen.[36] The Dutch military success, initially short-lived as Bahia was recaptured only one year later, raised hopes of a Protestant counterbalance to the Spanish and Portuguese dominance in South America. Rößlin’s newspaper put particular emphasis on this event: while Atlantic news consistently outweighed his reports on Asia, in 1624, of his 122 reports on ‘the Indies’, 121 addressed South America.

Even though the Dutch West India Company had investors in Augsburg and Strasbourg, the massive appeal of the news from Brazil in the south and south-west of Germany can best be understood in the context of the military developments in the previous years and their coverage in contemporary media. Between 1620 and 1622, the Spanish Army of Flanders under the command of Ambrosio Spinola and the troops of the count of Tilly had invaded the Palatinate and taken all of its major Protestant cities. While news coverage of the Americas had not yet reached the scale of the late 1620s and early 1630s, the attention to the Spanish overseas connection was already developing. News reports from The Hague and Amsterdam often related the seizing of Spanish ships in the Caribbean and the Atlantic and explicitly addressed the strategic importance of maritime war for the anti-Habsburg struggle at home.[37] This aspect was even more pronounced in reports from Cologne, which because of its large contingent of immigrants from the Southern Netherlands had long been an important hub for news from the Low Countries.[38] The Cologne correspondents of southern German newspapers added an extra layer of interpretation to maritime events and prepared them for a specifically German news market by highlighting their relevance for the political situation within the Holy Roman Empire.[39] Occasionally the war in Brazil was even directly linked to specific military campaigns in Germany: in December 1624, Rößlin reported that Tilly had had to send part of his troops to the Low Countries because the Spanish Army had shipped too many soldiers to Brazil and now lacked manpower in Europe.[40] As he suggested, the Dutch struggle for Bahia could have immediate consequences for the Spanish strategy in Germany.

The 1624 news about a spectacular Protestant victory in the South Atlantic reached the German media landscape at a moment when Spanish superiority seemed largely unchallenged, at least from a southern German perspective. During the Iberian Union that lasted from 1580 and 1640, contemporaries often regarded Spain and Portugal as one singular complex of power, although Brazil was formally governed by the Council of Portugal. The conquest of Bahia promised a weakening of Habsburg imperial dominance, and Rößlin’s newspapers highlighted the financial blow to the Spanish Crown.[41] In addition, the taking of Bahia both promised access to the rich sugar territories of Brazil and sparkled Dutch hopes for expansion into South America. Another Dutch maritime campaign, led by Admiral Jacques l’Hermite, raised such expectations further. L’Hermite and the so-called Nassau fleet had sailed around Cape Horn to attack Spanish territories from the other side of the South American subcontinent and even though news from this expedition was infrequent, newspapers did their best to follow its course. Although L’Hermite had died in early June 1624 in Peru and his fleet had set off for Indonesia, German newsmakers continued to publish news of spectacular Dutch victories on the South American west coast until early 1625.[42] For the German news market, reports of Dutch military success proved the catalyst for a steady diet of reports from the South Atlantic. From now on, South American, Caribbean and, to a lesser extent, African news was reported on a regular basis, even in years with fewer newsworthy events.[43] In that sense, the Dutch attack on Bahia prepared the ground for a German news culture of which transoceanic information was a stable component.

Throughout the entire period of the Thirty Years War, Brazil would continue to play a key role in Atlantic news coverage, and German newspapers reported not only actual events in Pernambuco or Bahia but also their public reception in the Netherlands and, to a lesser extent, the Iberian Peninsula.[44] The Dutch surrender in Bahia in 1625 was covered as closely as had been their surprising victory in 1624. News about the outcome of the Dutch-Portuguese battle was initially mistrusted, and a mass of incoming reports described smaller skirmishes and rearguard actions in detail. As one Cologne correspondent reported, bets about the final outcome were placed not only in Amsterdam but also in the German Rhineland.[45] After news of the Spanish and Portuguese victory had been confirmed, Rößlin’s paper extensively covered the public reaction in the Northern Netherlands, and his reports from Amsterdam, The Hague and Cologne sketched angry responses from both the authorities and the urban community. On 10 September, he reported that someone had nailed a sign at the doors of the West India House that read, ‘This house is for rent and can be moved into immediately. It is understood that the Dutch will no longer be bringing in there anything from the West Indies.’[46] While the place and date of this particular source were not indicated, which was rather unusual, Rößlin issued a second report, written in The Hague on 2 September, which confirmed that the situation was even worse and that an angry mob had looted the building and smashed its windows and doors.[47]

In the following months, reports concerning responsibility for the defeat circulated. As Rößlin and others related, commanders were dragged out of their beds and taken into custody in the night, soldiers blamed their superiors and rumours about torture and executions spread.[48] Dutch Bahia was not only a short-lived distant colony but also a key issue in fierce domestic debates.[49] From a German perspective, it was crucial to understand these debates in order to anticipate Dutch designs, and newsmakers frequently reported on the strategic visions of the Dutch West Indian Company and their effect on diplomatic negotiations for peace in Europe. Five years later, when the Dutch launched a second campaign in Brazil, a Cologne report in Lucas Schultes’ newspaper straightforwardly proclaimed, ‘the attack on Pernambuco has smashed the entire bottom out of the barrel of a much-desired truce agreement’.[50]

III. AMERICAN BULLION, GERMAN BLOOD

Even more closely linked to the political and military situation in Germany was another Atlantic topic: the yearly flow of South American silver and gold to Spain. In the early 1620s, when Spanish troops occupied the Palatinate, and in the mid-1630s, when the Spanish Crown supported the emperor’s troops financially, Spanish liquidity became an important factor for the course of Thirty Years War.[51] The Habsburg dependency on riches from the Americas was a recurring theme in the German newspapers, especially in the context of the war. Since the early 1620s, German news correspondents had added information about Spanish money to their war reports, especially news writers from Cologne, whose letters often merged incoming information from various places. In their accounts of the developing campaigns of Habsburg army commanders in Westphalia and Brabant, the Cologne reports frequently evaluated the chances of success by referring to the arrival of South American silver.[52] Reports that suggested such direct connections only increased in subsequent years.In 1628, the Dutch admiral Pieter Pieterszoon Heyn landed a spectacular coup by capturing the Spanish treasure fleet in the Bay of Matanzas in Cuba, an episode that received great attention in German, and especially Protestant, newspapers. While the event had taken place in September 1628 and was first reported in late November, it filled the first pages of Schultes’ newspaper until early April 1629.

His Continuation der Augsburger und Nürnberger Zeitung reported new details every week and sometimes used the same reports to highlight various aspects of Heyn’s victory.[53] Once this news cycle was exhausted, Schultes turned to the effect of the capture of the treasure fleet on the war in Europe and reported on recruitment and the concerns about mutiny among Spanish soldiers who could no longer be paid. The coverage of Heyn’s coup, celebrated as a Protestant victory over the Spanish Habsburg enemy, reflects the agency of individual newsmakers and shows how loosely the relata refero principle was applied. While Schultes did his best to put every grain of information into his paper, and his reports and lists of captured goods often filled several pages, his colleagues in Catholic Munich, who largely based their coverage on the same sources, published only fragments of what Protestant newsmakers related and mentioned the Spanish defeat as briefly as possible. In 1629, when the strategic city of Bois-le-Duc was besieged and eventually captured by Frederick Henry of Orange-Nassau, German newsmakers noted that money from the ships captured in Cuba supported his army. The repercussions of Heyn’s victory were felt far into the Holy Roman Empire: in Wroclaw, far in the east, news writers reported on deliberations in Baltic and eastern European cities about reconsidering peace and trade negotiations as the European balance of power was shifted by the recently filled Dutch war chest. As magistrates in Danzig and elsewhere calculated, Spanish-funded campaigns against the Swedish were now severely undercut: the Spanish loss of silver would reverse the military situation in the Baltic and give Protestant and anti-Imperial powers all over Europe a new boost.[54]

The flow of American bullion to Europe and its use for the war in Germany, the Netherlands and Italy were controversial issues in news cultures in several European countries, and reports on the coining of Spanish silver in England and its transfer to the European continent even played a role in the temporary ban of English newsbooks between 1632 and 1638.[55] While incoming gold and silver were indeed crucial for the financing of the war in Europe, German newsmakers often exaggerated the immediate impact of the silver fleet’s arrival on local events. As Rößlin recounted, Cologne and surrounding cities commissioned repair works on their military fortifications in anticipation of receiving funds from Spain, a rather speculative prospect. After a Swedish campaign in the winter of 1632 had left strategic defensive fortifications in the Rhineland in a desolate state, Cologne news writers asserted that the arrival of the silver fleet had led to massive rebuilding efforts in Deutz.[56] Even if Spanish financial support for rearmament and rebuilding was more than uncertain, news of the silver fleet served for rough calculations of future military developments. Reports about the fleet were frequently annotated with anticipatory comments about the renewed morale of soldiers and the prospects of new campaigns. Correspondents not only in Cologne but also in The Hague, Antwerp and Rome commented on the silver shipments with short remarks like ‘The Spaniards are walking with their heads high again’ or ‘This will produce willing soldiers.’[57] News about American bullion shipments was thus also news about the war at home.

In the course of the first half of the seventeenth century, the link between the Thirty Years War and American silver and gold became a commonplace of the German media landscape. Poets like Martin Opitz and Friedrich von Logau stressed the suffering of European civilians in this context and, in addition, addressed the economic impact of silver shipments on European societies. In several of his poems, Logau contrasted the ‘New World’ with the ‘Old’ and identified the flow of gold as both a cause of inflation and a catalyst of war in Germany: not only did the riches from America drive Europe into collective ‘insanity’, they also were the very reason that the ‘Old World’ was now ‘entirely covered in blood’.[58] Even in media genres in which the Americas typically served as the otherworldly object of European imagination and projection, factual politics and economic realities had made an entry: the two continents were now tied together in a union that resulted in a nightmarish new world of violence and bloodshed on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean—not only in the colonized parts of South America but also on the battlefields of Germany.

IV. THE HEILBRONN LEAGUE AND THE RHETORIC OF GLOBAL WARFARE

The dense news coverage of transatlantic events and developments in relation to the Thirty Years War was soon discovered as an opportunity by overseas trade agents and used for specific political purposes. In 1633, Willem Usselincx, self-proclaimed founder of the Dutch West India Company and agent in the service of the Crown of Sweden, launched a media campaign in Germany to attract German investors for the Swedish South Company. Usselincx, a native of Antwerp and fervent Reformed Protestant, was already famous for his agitating anti-Catholic and anti-Spanish pamphlets, and his polemical skills were now displayed to a German audience. With long years of experience in international long-distance trade as well as in lobbying and petitioning for new economic enterprises, Usselincx used several communication channels to approach potential German investors on behalf of the Swedish government. In 1630, he travelled from Emden to the Baltic, where he contacted German merchants, magistrates and nobles and wrote advertising letters to southern German cities. In the following years, Usselincx authored several short treatises that explained the necessity of participation in Atlantic and Asian trade to a German audience. Enthusiasm for investment in the Swedish South Company, founded in 1626, remained modest: while entrepreneurs in cities like Augsburg, Frankfurt and Strasbourg had invested substantially in the Dutch and English East and West India trading companies since the 1620s, the viability of this new Swedish company was not widely accepted.[59]

In 1632, Usselincx took a more immediate approach and decided to direct his efforts at an imminent military alliance between Sweden and most of the Protestant princes in the south and south-western Empire. In November 1632, Gustavus Adolphus II invited these German rulers to meet in Heilbronn the following spring. The negotiations were continued by Swedish chancellor Axel Oxenstierna after the king’s death at the battle of Lützen and resulted in the foundation of the Protestant Heilbronn League in 1633, a military alliance that was intended as a counterbalance to the dominant Imperial and Spanish forces in Germany. Usselincx had great hopes for this new Protestant union: in the months before the meetings, he prepared and collected a number of texts to advertise the scheme that were compiled and published under the title Argonautica Gustaviana and presented to the princes in Heilbronn.[60] Usselincx offered the Protestant estates not only German participation in the Swedish South Company, but also the opportunity to establish their own German chambers within the trade organization. He argued that Germany’s geographical location was far better suited for long-distance trade than was the Swedish coastline beyond the Oresund. Concentrating the Swedish trade platforms on the north-western German seaports would give both Sweden and Germany better access to trade around the globe.

In Heilbronn, Usselincx had himself represented by Hector Mithobius, a Lutheran clergyman with connections to the dukes of Württemberg, a decision that was undoubtedly informed by Usselincx’s suspect reputation as a radical Calvinist. Mithobius put particular emphasis on the vital importance of overseas trade for the course of the war in Germany.[61] This rhetorical strategy was not surprising in the context of overseas news coverage in Germany: in this crucial period of the Thirty Years War, strictly economic arguments were not enough to attract investors in the circles of Imperial princes. Mithobius and Usselincx insisted that the war could not be won in Germany itself, as the overseas resources of the Spanish and Imperial forces were virtually inexhaustible. It was therefore essential not only to establish secure Protestant access to colonial riches but also to cut off the enemy from his resources.[62]

Presenting the war in Germany as part of a global conflict reflected the discourse of contemporary Protestant newspapers. Princes like the dukes of Württemberg, who not only read Rößlin’s newspaper but even had their secretaries oversee its publication, were already familiar with this rhetoric, and Usselincx had reason to expect they would respond to his ideas.[63] By explicitly addressing the downside of the Dutch Brazilian project, Usselincx revealed that he assumed his German audience would be well-informed about the most recent geopolitical developments. He noted that the timing and the strategy of the Brazilian design had been far from ideal and that the situation would have even been worse had Brazil not been such an extraordinarily rich colony.[64]

He also claimed that he had warned the Dutch States General as early as 1624—had they only listened to his advice, Bahia might still be Dutch and the northern parts around Recife could then be exploited in a far more profitable way. With his knowledge and experience, he continued, Sweden and the German Protestants would be able to outperform the Dutch overseas projects and use the riches they could expect to acquire to win the war in Europe. Ironically, referring to recent Dutch failures in Brazil proved an ill-chosen strategy: only months after the Heilbronn meeting and on until 1635, the Dutch were able to substantially expand their territory there, a development that was soon reported and celebrated in Dutch and German news media.[65] Dutch Brazil reappeared as a success story and the need to look for alternative locations for investment in colonial trade was thereby vitiated.

Usselincx’s German media campaign did not only adopt existing news discourses—it became a news event in itself. In the autumn edition of the 1633 Frankfurt Messrelationen, the plans to found German chambers were broadly reported and the publisher, at that time Anna Latomus, offered Usselincx a wide platform for his ideas. Latomus’s coverage of the Swedish proposal and of the discussion of Atlantic and global trade at the Heilbronn meeting was disproportional, especially for this specific medium. The bi-annual Messrelationen selected and structured their reports in a much more topical and coherent way than the weekly newspaper could, and they only covered the most relevant events of the last six months. During the Thirty Years War, this print genre largely focused on decisive battles, sieges and political negotiations. Yet the second issue of 1633 opened with the Heilbronn meetings and reserved the first thirty pages for this topic, largely focusing on Usselincx’s proposal for German Protestant participation in the Swedish South Company. In addition to a report on the course of the negotiations in Heilbronn, Latomus included no fewer than fifteen pages with original documents from the Argonautica Gustaviana and again highlighted the vital significance of global commerce for the Protestant cause in the German war.[66] The prospective participation in a Swedish-led trading company outweighed other news, which included the Protestant victories in the Battle of Oldendorf and the siege of Landsberg. As Latomus reported it, the Protestant princes had indicated their support for Usselincx’s and Oxenstierna’s plans. These plans, however, were never realized: while the South Company was able to attract some individual investors, the German chambers failed to materialize in the chaotic years between 1633 and 1635. The subscription term set by Usselincx was short and the gloomy image of Dutch Brazil that was deployed to attract investors for a Swedish alternative to the Dutch West India Company was disproven by newer reports. In addition, the German seaports that were deemed necessary were not available for this project. The magistrates of Hamburg made clear that the city could not afford to endanger its trade with Spain by opening its ports to the new company, while smaller seaports like Emden were even more afraid of an open confrontation with the Spanish-Imperial powers.[67] When most Protestant rulers signed a peace treaty with the emperor in 1635, Sweden was left politically isolated in Germany, bringing a definitive end to Usselincx and Oxenstierna’s plans. Direct German involvement in colonial overseas trade did not materialize until the foundation of the Brandenburg trading companies in the 1680s.

V. CONCLUSION

In October 1624, Otto von Estorf noted in his chronicle: On 15 October, the Countess Palatine has given birth to a young prince and has now six sons and 2 daughters.Tilly has taken the castle of Cassel as his headquarters and his army shall now move to the Netherlands to support Spinola.Commander Van Dordt has been shot through the head with an arrow by an Indian at the fortification of … [sic] in the West-Indies, which left him dead.[68]Estorf recorded these three unrelated events in the dry and tabular manner also found in the newspapers of his time. The death of Van Dordt is reported by Rößlin very similarly and, curiously, the name of the fortification where the Dutch officer was shot is lacking in both texts: while Estorf left a lacuna in his chronicle, the name is crossed out in the only surviving copy of Rößlin’s paper for that week.[69] While other contemporary print media that addressed events in the ‘New World’ often indulged in spectacular and marvellous descriptions of people, customs and landscapes, all such discourse is absent from the newspaper. Monstrous births, miracles or prodigious comets were not uncommon in early modern news media, but they were typically reported from rural areas in Germany, Poland or Italy and only very rarely from more distant places. Events in South America and India had become political facts of the same order as the birth of a prince in The Hague or the latest military campaign of a famous general in Germany. No longer functioning as the setting of either cannibalistic excesses or Spanish atrocities as had been the custom in the sixteenth century, the overseas world was now integrated into European political, economic and military realities. Neither the chronicler Estorf nor the critical reader of Rößlin’s newspaper was satisfied with ambiguity, whether about the name of the Brazilian fort where Van Dordt had died or the place where General Tilly had set up his headquarters: they left a lacuna until fuller information could be received, regardless whether that information was about central Germany or coastal Brazil.The immediacy of events in the Americas and their rather dry and factual rendition incorporated them into the discourse of political contemporaneity in Europe and enabled contemporaries to situate overseas and domestic issues in the same global contexts. Newsmakers designed reports with the particular interests of their readership in mind. Notwithstanding German investments in the Dutch and English trading companies, the focus of the German coverage of overseas news was primarily not economic but geopolitical. While claims of neutrality and impartiality were prerequisites for early German newspapers, publishers selected and edited their reports according to a news culture that was dominated by the Thirty Years War and the need to make sense of the chaotic reality of changing strategies and alliances. The publication of reports from all over the globe promised a fuller and more comprehensive understanding of domestic affairs and an evaluation of their significance in global geopolitics.While the coverage of non-European events in German newspapers increased, the focus on Europe prevailed throughout the seventeenth century. Short-lived bi-weekly newspapers with exclusively Asian news appeared later, in the 1680s, as an experiment that also provided the reader with ethnographical information about China, Moghul India or Persia.[70] During the Thirty Years War, however, such distant news was thought relevant only for its impact on Germany and more widely in Europe. While scholarship on the early modern global imagination and on interconnectedness is still often characterized by a focus on empire-building and imperial expansion, these observations suggest that at least in the case of Central Europe, a global consciousness could exist outside an imperial context.[71] Paradoxically, it was the political disintegration of the Empire itself that stimulated a sense of global connectedness in military and economic terms. While elsewhere in Europe imperial structures and centralizing states managed the flow of information to control public discourse, the largely self-organizing and decentralized news web in the German territories generated a media landscape shaped by attempts to make sense of a chaotic political reality.[72] Newsmakers eagerly collected transoceanic news in order to identify and comprehend global factors behind the war at home. As Sebastian Conrad has argued, it is not so much the links and interconnections between countries and continents that allow for a truly global historical approach as the impact of these connections on existing social and cultural structures.[73] The transoceanic exchange of information and its medial dissemination in Germany clearly had such a transformative impact. While sensational accounts of faraway places and marvellous travel narratives were available throughout the later Middle Ages and the early modern period, the periodical flow of information in a new medium integrated Atlantic developments into the geographical and historical continuum of German courtly and urban society. The representation of the Americas was no longer dominated by discourses of marvel and wonder but became part of European contemporaneity.[74] Simultaneously, military and economic developments in the Atlantic world served as an interpretive framework for European politics, and domestic affairs could no longer adequately be comprehended without reference to transcontinental geopolitics. While the circulation of distant news reports in itself cannot account for a ‘globalization’ in cultural and economic terms, understanding the war in Germany as part of a global conflict implied understanding Germany itself in global terms.

Notes:

1 S. H. Steinberg, ‘The Thirty Years’ War: A New Interpretation’, History, 32 (1947), pp. 89–102, here pp. 89–90. For an extended and more detailed account of this argument, see N. M. Sutherland, ‘The Origins of the Thirty Years’ War and the Structure of European Politics’, English Historical Review, 107, 424 (1992), pp. 587–625. For a critique of Steinberg’s chronological argument, see G. Mortimer, ‘Did Contemporaries Recognize a “Thirty Years War”?’ English Historical Review, 116, 1 (2001), pp. 124–36, here pp. 124–5, 135–6.

2 J. K. Thornton, ‘The Kingdom of Kongo and the Thirty Years’ War’, Journal of World History, 27, 2 (2016), pp. 189–2013; G. Parker, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century (2nd edn, New Haven, 2017; 1st edn, 2013), pp. 169–97; S. Richter, ‘A Peace for the Whole World? Perceptions and Effects of the Peace Treaty of Münster (1648) and the World outside Europe’, in O. Asbach and P. Schröder (eds), The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years’ War (London, 2014), pp. 319–39; W. Behringer, ‘Der erste Weltkrieg: marodierende Heere und die Machtspiele europäischer Herrscher setzten Deutschland im letzten Jahrzehnt der Kämpfe fürchterlich zu’, in D. Pieper and J. Saltzwedel (eds), Der Dreißigjährige Krieg: Europa im Kampf um Glaube und Macht, 1618–1648 (Munich, 2012), pp. 173–85; P. Wilson, The Thirty Years’ War: Europe’s Tragedy (London, 2009), pp. 116–31, 368–9. For an earlier contextualization of the Thirty Years War in a global historical context, see G. Parker, The Thirty Years’ War (London and New York, 1984).

3 Volkmar Happe, Chronicon Thuringiae, ed. H. Medick, N. Winnige and A. Bähr, n.d., http://www.mdsz.thulb.uni-jena.de/happe/quelle.php, part 1, fol. 23v: ‘[…] der blutige Böhmische Krieg […], der viel Jahr continue aneinander gewehret, fast die gantz Welt durchkrochen und alle Lande verderbet’ (italics mine).

4 Happe, Chronicon Thuringiae, part 1, fol. 24v: ‘Den 3. November 1618 ist ein schrecklicher Compet [sic] am Himmel erschienen, […] darauf in aller Welt Krieg, Aufruhr, Blutvergießen, Pestilentz und theure Zeit und unaussprechlich Unglück erfolget.’ For other chroniclers and pamphleteers who mention this comet, see A. Bähr, Der grausame Komet: Himmelszeichen und Weltgeschehen im Dreißigjährigen Krieg (Reinbek, 2017); J. van de Löcht, ‘“Krieg/ groß Sterben/ vnd Hungers pein/ Bringt mit sich der Cometen schein”: publizistische Folgen der Kometen von 1607 und 1618/19 im Vergleich’, Daphnis, 47, 1–2 (2019), pp. 85–112; Mortimer, ‘Did Contemporaries Recognize a “Thirty Years War”?’, p. 128

5A. E. E. L. von Duve (ed.), ‘Des Schwerinschen Dompropsten und Ratzeburger Domherrn, Otto von Estorf, Diarium belli Bohemici et aliarum memorabilium (vom 23. Mai 1618 bis zum 10. März 1637), nebst einer Vorerinnerung des früheren Besitzers dieses Manuscripts’, Archiv des Vereins für die Geschichte des Herzogthums Lauenburg, 6, 2 (1900), pp. 1–52, here pp. 34–5, 38–9; Landesarchiv Sachsen-Anhalt, Dessau, Z 18 A 9b Nr. 14 I–XIV, Christian II. van Anhalt-Bernburg, ‘Tagebücher’, 7; 20 and 24 Dec. 1628. On American and Asian events in manuscript chronicles during the Thirty Years War, see also H. Berg, Military Occupation under the Eyes of the Lord: Studies in Erfurt during the Thirty Years’ War (Göttingen, 2010), pp. 322–7.

6See e.g. E. Schmitt, ‘The Brandenburg Overseas Trading Companies in the Seventeenth Century’, in L. Blussé and F. Gaastra, Companies and Trade (Leiden, 1981), pp. 159–76; J. Pohle, Deutschland und die überseeische Expansion Portugals im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert (Münster, 2000), pp. 255–82; C. Ebert, Between Empires: Brazilian Sugar in the Early Atlantic Economy, 1550–1630 (Leiden and Boston, 2008), pp. 26–32; K. Weber, ‘Deutschland, der atlantische Sklavenhandel und die Plantagenwirtschaft der Neuen Welt’, Journal of Modern European History, 7 (2009), pp. 37–67, here p. 43. Weber nuances the German retreat from Atlantic trade in the first half of the seventeenth century by pointing at German investments in Dutch and English overseas trade companies during the 1620s. On German intellectual and economic engagement with the Americas and its gradual decline in the late sixteenth century, see C. Johnson, The German Discovery of the World: Renaissance Encounters with the Strange and Marvelous (Charlottesville, 2008), pp. 17, 187–95, 204; R. Pieper, Die Vermittlung einer neuen Welt: Amerika im Nachrichtennetz des habsburgischen Imperiums, 1493–1598 (Mainz, 2000), pp. 282–4.

7For a nuanced discussion of the transformation of the Fugger trading activities between the second half of the sixteenth century and the Thirty Years War, see M. Häberlein, The Fuggers of Augsburg: Pursuing Wealth and Honor in Renaissance Germany (Charlottesville, 2012), pp. 99–124.

8For an overview on the evolution of this argument, see W. Neuber, Fremde Welt im europäischen Horizont: zur Topik der deutschen Amerika-Reiseberichte der Frühen Neuzeit (Berlin, 1991), pp. 276–82. On Americana on the sixteenth-century German book market see also Pieper, Die Vermittlung einer neuen Welt, pp. 44–9.

9 For a broader discussion of the engagement of scholarship on early modern Germany with global historical approaches, see R. Dürr, R. Po-Chia Hsia, C. Johnson, U. Strasser and M. Wiesner-Hanks, ‘Globalizing Early Modern German History’, German History, 31, 3 (2013), pp. 366–82.

10 Continuation der Augsburger und Nürnberger Zeitung, published by Lucas Schultes in Öttingen and from 1632 until 1634 in Nördlingen (hereafter: Schultes); Zeittungen, published by Johann Weyrich Rößlin (father and son) in Stuttgart (hereafter: Rößlin); Relation, published by Johann Carolus in Strasbourg (hereafter Carolus); Wochentliche Ordinari Zeitung, published by Anna Berg and her son Adam in Munich (hereafter: Berg) and Ordentliche Wochentliche Postzeitungen, published by Johann Lucas Straub, also in Munich (hereafter: Straub). For more bibliographical details on these newspapers, see E. Blühm and E. Bogel, Die deutschen Zeitungen des 17. Jahrhunderts: ein Bestandsverzeichnis mit historischen und bibliographischen Angaben (Bremen, 1971), part 1, pp. 64–7; 37–9; 1–4; 73–5; 77–80. The titles of these newspapers are not consistent across every issue and I indicate only the name of the publishers to avoid confusion.

11 B. Schmidt, Innocence Abroad: The Dutch Imagination and the New World, 1570–1670 (Cambridge, 2001), pp. 291–305; M. van Groesen, The Representations of the Overseas World in the De Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634) (Leiden and Boston, 2008), pp. 149–57, 320–1; P. Schmidt, Spanische Universalmonarchie oder ‘teutsche Libertet’: das spanische Imperium in der Propaganda des Dreißigjährigen Krieges (Stuttgart, 2001), pp. 273–97.

12 For an overview of Europe’s news media in the early modern period, see A. Pettegree, The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know about Itself (London, 2014). On the German Messrelationen, which are often considered predecessors of the printed newspaper, see E. B. Körber, Messrelationen: Geschichte der deutsch- und lateinischsprachigen ‘messentlichen’ Periodika von 1588 bis 1805 (Bremen, 2016); J. Jacoby, ‘The Frankfurt Messrelationen, 1591–1595’, Print Quarterly, 32, 2 (2018), pp. 131–59.

13 J. Weber, ‘Strassburg, 1605: The Origins of the Newspaper in Europe’, German History, 24, 3 (2006), pp. 387–412.

14 J. Weber, ‘Der große Krieg und die frühe Zeitung: Gestalt und Entwicklung der deutschen Nachrichtenpresse in der ersten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts’, Jahrbuch für Kommunikationsgeschichte, 1 (1999), pp. 23–61; H. Böning, ‘Dreißigjähriger Krieg und Öffentlichkeit: Zeitungsberichterstattung als erste Rohfassung der Geschichtsschreibung’, Daphnis, 47, 1–2 (2019), pp. 25–67; W. Behringer, ‘Veränderung der Raum-Zeit-Relation: zur Bedeutung des Zeitungs- und Nachrichtenwesens während der Zeit des Dreißigjährigen Krieges’, in B. von Krusenstjern and H. Medick, Zwischen Alltag und Katastrophe: der Dreißigjährige Krieg aus der Nähe (Göttingen, 1999), pp. 39–81.

15 J. J. Berns, ‘Zeitung und Historia: die historiographischen Konzepte der Zeitungstheoretiker im 17. Jahrhundert’, Daphnis, 12, 1 (1983), pp. 87–110, here p. 95.

16Schultes always put Dutch and Spanish news on the first pages, while Rößlin was less consistent in ordering his material but typically started with correspondence from western Europe, for example from the Low Countries, France, Spain or England. Hamburg publishers, by contrast, tended to start with Central Europe.

17 Weber, ‘Strassburg, 1605’, p. 392. For a critical discussion of this assumption, see W. Behringer, Im Zeichen des Merkur: Reichspost und Kommunikationsrevolution in der Frühen Neuzeit (Göttingen, 2002), p. 369.

18 Berns, ‘Partheylichkeit and the Periodical Press’, pp. 131–2.

19 Weber, ‘Strassburg, 1605’, p. 393.

20 Behringer, Im Zeichen des Merkur, pp. 368–9.

21 See e.g. Schultes, 1628, nos. 15 and 16; 17 and 18; Rößlin, 1625, 10 and 17 Dec.; 1627, 27 Oct. and 3 Nov.

22 See e.g. Wochentliche Donnerstags Zeitung, 1628, no. 50 (Venice, 3 Sept.); 1630, no. 36 (Augsburg, 18 Aug.) 1631, no. 36 (Regensburg, 27 Aug.). That this polemical sneer also appears in the newspaper’s reports from Catholic Venice suggests that this spelling was chosen not by the correspondents but by the Hamburg editor, Martin Schumacher.

23 J. J. Berns, ‘Partheylichkeit and the Periodical Press’, in K. Murphy and A. Traninger (eds), The Emergence of Impartiality (Leiden and Boston, 2013), pp. 87–139, here p. 132.

24 On narrativity and the production of ‘eventfulness’ in news reports on the Thirty Years War, see N. Detering, ‘Ereignishaftigkeit und Narrativität in der deutschen Publizistik des Dreißigjährigen Krieges’, Scientia Poetica: Jahrbuch für Geschichte der Literatur und Wissenschaften, 22 (2018), pp. 257–69.

25 See for examples the issues of Schultes’ Continuation der Augsburger und Nürnberger Zeitung between September 1628 and early 1629. It is in fact rather difficult to systematically separate European and non-European news in seventeenth-century German newspapers since most reports about the Americas also contained news from Europe. Reports from Amsterdam, for example, related events in the Netherlands but they included maritime news from the Americas and Asia. For a systematic overview of places of correspondence in the earliest printed newspapers, see J. Hillgärtner, German Newspapers 1605–1650: A Bibliography, 2 vols (forthcoming).

26 For an extensive discussion of American news in handwritten newsletters in sixteenth-century Germany, see Pieper, Die Vermittlung einer neuen Welt, esp. pp. 18–34, 128–38, 238–41.

27 S. Barbarics and R. Pieper, ‘Handwritten Newsletters as a Means of Communication in Early Modern Europe’, in F. Bethencourt and F. Egmond (eds), Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe, vol. 3: Correspondence and Cultural Exchange in Europe, 1400–1700 (Cambridge, 2007), pp. 53–79, here p. 63.

28 The total number of Rößlin’s news reports in 1624 was 958. The 121 reports that contained Atlantic news did not exclusively focus on the Americas but typically included both European and American maritime news.

29 Schultes, 1630, 14/24 Feb. The bi-confessional town of Öttingen used both the Julian and Gregorian calendar systems simultaneously and Schultes’ newspaper always indicated both dates. I use only Gregorian dates in the main text. In the footnotes, I follow the original dates as indicated in the newspapers.

30 Berg, 1630, no. 7. Berg did not date his news sheets and only indicated the dates of the incoming reports. Other Munich publishers were more reluctant to report the unconfirmed news about Brazil and waited until May to bring any reports about Brazil. See Straub, 1630, XX (Amsterdam, 27 Apr.).

31 Abraham Verhoeven, Wekelijcke Tijdinghe, 1630, 15 Mar. On the chronology of the Brazilian reports in the Low Countries, see M. van Groesen, ‘(No) News from the Western Front: The Weekly Press of the Low Countries and the Making of Atlantic News’, Sixteenth Century Journal, 44, 3 (2013), pp. 739–60.

32 First rumours were already being spread in January and were then confirmed in February, even though the attack on Pernambuco only started on 14 February: Schultes, 1630, no. 3 (The Hague, 15 Jan.); no. 4 (The Hague, 15 Jan.); no. 6 (The Hague, 5 Feb.); no. 7 (The Hague, 5 Feb.); Wochentliche Donnerstags Zeitung, 1630, no. 11 (The Hague, 29 Feb.).

33 Amsterdam publisher Jan van Hilten reported the Dutch victory in Pernambuco no sooner than 27 April—three months later than Schultes. See Courante uyt Italien, Duytslandt, &c., 1630, 27 Apr.

34 Rößlin, 1624, 7 Aug. (Cologne, 4 Aug.): ‘Und von Antorff hat man, daß die Donkircher Schiff ein sehr reich beladen Holländisch Jagtschiff aus Indien kommend, zu Donkirchen eingebracht haben, dahero die Staden keine Aviso von ihren Schiffen haben.’35On the sixteenth-century news coverage of the Spanish treasure fleet, see Pieper, Die Vermittlung einer neuen Welt, pp. 213–35. On the perceived geopolitical impact of American silver on Europe, see F. Ambrosini, ‘Venetian Diplomacy, Spanish Gold, and the New World in the Sixteenth Century’, in E. Horodowich and L. Markey (eds), The New World in Early Modern Italy, 1492–1750 (New York, 2017), pp. 47–58, there pp. 51–2.

35 On the sixteenth-century news coverage of the Spanish treasure fleet, see Pieper, Die Vermittlung einer neuen Welt, pp. 213–35. On the perceived geopolitical impact of American silver on Europe, see F. Ambrosini, ‘Venetian Diplomacy, Spanish Gold, and the New World in the Sixteenth Century’, in E. Horodowich and L. Markey (eds), The New World in Early Modern Italy, 1492–1750 (New York, 2017), pp. 47–58, there pp. 51–2.

36 On the intermedial connections in the German news coverage of this event, see M. Schilling, Bildpublizistik der frühen Neuzeit. Aufgaben und Leistungen des illustrierten Flugblatts bis um 1700 (Tübingen, 1990), pp. 113–15; Schmidt, Spanische Universalmonarchie, pp. 377–8.

37 See e.g. Rößlin, 1622, 12 and 19 Jan.; 19 Apr.; 4 May; 1623, 31 May; 28 June.

38 J. Hillgärtner, ‘Netherlandish Reports in German Newspapers, 1605–1650’, Early Modern Low Countries, 2, 1 (2018), pp. 68–87; A. Stolp, De eerste couranten in Holland: Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der geschreven nieuwstijdingen (Haarlem, 1938), pp. 35–48.

39 Rößlin, 1623, 8 Feb. (Cologne, 29 Jan.); 31 May (Cologne, 29 May); 28 June (Cologne, 25 June).

40 Rößlin, 1624, 4 Dec. (Geneva, 20 Nov.).

41 Rößlin, 1624, 5 June (London, 11 May).

42 See e.g. Carolus, 1624, no. 1 (Amsterdam, 23 Sept. 1623); Rößlin, 1624, 14 Aug. (Antwerp, 5 Aug.); 18 Sept. (The Hague, 9 Sept.); 25 Sept. (The Hague, 16 Sept.); 2 Oct. (The Hague, 23 Sept.); 9 Oct. (30 Sept.); 20 Nov. (Amsterdam, 12 Nov.; The Hague, 13 Nov.); 27 Nov. (Cologne, 27 Nov.); 4 Dec. (Amsterdam, 24 Nov.); 1625, 29 Jan. (Amsterdam, 19 Jan.); 5 Mar. (Paris, 17 Feb.). On Jacques l’Hermite’s expedition and its Dutch reception, see B. Schmidt, ‘Exotic Allies: The Dutch-Chilean Encounter and the (Failed) Conquest of America’, Renaissance Quarterly, 52, 4 (1999), pp. 440–73.

43 For reports that stress the strategic importance of the coasts of West Africa, see e.g. Rößlin, 1624, 31 Jan. (Rome, 13 Jan.); 2 Oct. (The Hague, 23 Sept.); 11 Dec. (Paris, 19 Nov.); 1633, 1 June (The Hague, 23 May); 8 June (The Hague, 28 May); Einkommende Wochentliche Zeitungen, 1638, no. 8 (Amsterdam, 2 Jan.); no. 28 (Antwerp, 30 Jan.).

44 See e.g. Schultes, 1625, i (Amsterdam, 7 Oct.); Rößlin, 1625, 10 Sept. (The Hague, 2 Sept.); 15 Oct. (The Hague, 6 Oct.); 22 Oct. (The Hague, 13 Oct.); 29 Oct. (Amsterdam, 18 Oct. and The Hague, 20 Oct.); 5 Nov. (Cologne, 26 Oct.).

45 Rößlin, 1625, 30 July (Cologne, 27 July); 27 Aug. (Cologne, 24 Aug.). On bets on Brazil, see also M. van Groesen, Amsterdam’s Atlantic: Print Culture and the Making of Dutch Brazil (Philadelphia, 2017), p. 68.

46 Rößlin, 1625, 10 Sept. (‘Extract unterschiedlicher Schreiben’): ‘Diß Haus stehet zu verleihen, und gleich darein zuziehen. Verstehet sich, die Stadische werden aus WestIndien nichts mehr darein bringen.’

47 Rößlin, 1625, 10 Sept. (The Hague, 2 Sept.).

48 Schultes, 1625, i (Amsterdam, 7 Oct.); Rößlin, 1625, 15 Oct. (The Hague, 6 Oct.); 22 Oct. (The Hague, 13 Oct.); 29 Oct. (Amsterdam, 18 Oct. and The Hague, 20 Oct.); 5 Nov. (Cologne, 26 Oct.); 1626, 25 Mar. (The Hague, 12 Mar.; 17 Mar.).

49 On Brazil as a point of debate in Dutch print and media culture, see Van Groesen, Amsterdam’s Atlantic, pp. 44–71.

50 Schultes, 1630, no. 19 (Cologne, 5 May): ‘Die eroberung Fernambuco [sic] stoßt dem verhofften Treves den Boden auß […].’ For more examples, see ibid., 1630, no. 27 (Amsterdam, 19 June); no. 39 (The Hague, 23 Sept.); Berg, 1630, no. 40 (The Hague, 28 Sept.). The Cologne reports in Schultes’ newspaper also link the arrival of goods from south-east Asia to the probability of future peace or truce negotiations. See e.g. Schultes, 1629, no. 50 (Cologne, 9 Dec.). On Brazil as an obstacle for peace and truce negotiations, see also J. Israel, The Dutch and the Hispanic World, 1606–1661 (Oxford, 1982), pp. 223–47.

51 On the impact of American bullion for the financing of Spanish troops in the Thirty Years War, see C. Kampmann, Europa und das Reich im Dreißigjährigen Krieg: Geschichte eines europäischen Konflikts (Stuttgart, 2008), p. 122; Wilson, The Thirty Years’ War, pp. 116–20. On newspapers as a source of information on early modern bullion flow from the Americas, see M. Morineau, Incroyables gazettes etfabuleux metaux: Les retours de tresors americains d’apres les gazettes hollandaises (XVI–XVIII siecles) (Cambridge, 1985).

52 See e.g. Rößlin, 1623, 8 Feb. (Cologne, 29 Jan.); 31 May (Cologne, 29 May); 28 June (Cologne, 25 June). Carolus’s Relation brought similar reports from The Hague. See e.g. Carolus, 1626, no. 34 (The Hague, 17 Aug.).

53 See e.g. Schultes, 1629, nos. 4; 5; 6; 7.

54 Schultes, 1629, no. 2 (Wroclaw, 2 Jan.): ‘[…] scheinet auch/ weiln die Holländer die Silberflotta bekommen/ etliche Potentaten und Stätte anders sinns werden möchten.’

55 J. E. E. Boys, London’s News Press and the Thirty Years’ War (Rochester, 2011), pp. 227–30. For more information on the English newsbook genre, see, see J. Raymond, The Invention of the Newspaper: English Newsbooks, 1641–1649 (Oxford, 1996); on other factors that informed the so-called Star Chamber Decree, see pp. 92–4.

56 Rößlin, 1633, 17 Aug. (Cologne, 11 Aug.): ‘Weil die Spannische Flotta 14. Millionen reich, in Sevilia angelangt, als werben hiesige Geistliche starck, wirdt auch an Bevestigung Deutz starck gearbeitet, und sein etlich Metalline Stück auß der Statt dahin, wie auch auff hiesige Bollwerck gelegt worden.’

57 Schultes, 1628, no. 1 (Antwerp, 30 Dec. 1627); no. 7 (Rome, 5 Feb.); Rößlin, 1633, 31 Aug. (The Hague, 15 Aug.).

58 Friedrich von Logau, Das Gold auß der Neuen Welt, cited in Gottlob Ephraim Lessing (ed.), Friedrichs von Logau Sinngedichte. Zwölf Bücher (Leipzig, 1759), p. 293: ‘Dann das Gold der neuen Welt macht, daß alte Welt sehr narrt/ Jene macht wol gar, daß alte Welt ganz in ihrem Blute starrt.’

59 Weber, ‘Deutschland, der atlantische Sklavenhandel und die Plantagenwirtschaft’, p. 43. On German investors among the nobility and urban elites, see R. Hildebrandt (ed.), Quellen und Regesten zu den Augsburger Handelshäusern Paler und Rehlinger: Wirtschaft und Politik im 16./17. Jahrhundert (Stuttgart, 2004), vol. 2, pp. 20–4, 205, 270. For a broader overview of German investments in the overseas and slave trade, see H. Raphael-Hernandez and P. Wiegmink, ‘German Entanglements in Transatlantic Slavery: An Introduction’, Atlantic Studies: Global Currents, 14, 4 (2017), pp. 419–35.

60 Willem Usselincx, Argonautica Gustaviana, Das ist nothwendige Nachricht von der neuen Seefarth und Kauff-handlung (Frankfurt, 1633).

61 C. Lichtenberg, Willem Usselinx (Utrecht, 1914), p. 169.

62 Usselincx, Argonautica Gustaviana, p. 29.

63 On Rößlin’s relationship with the Württemberg court, see J. Weber, ‘Kontrollmechanismen im deutschen Zeitungswesen des 17. Jahrhunderts: ein kleiner Beitrag zur Geschichte der Zensur’, Jahrbuch für Kommunikationsgeschichte, 6 (2004), pp. 56–73, there p. 66. The editorial comments of Württemberg court secretary Johann Jacob Gabelkover can hardly be characterized as strict censorship and most of his remarks concerned factual or spelling errors. In some cases, Gabelkover even supplied Rößlin with news, for example about the silver fleet. See e.g. Rößlin, 1624, 3 July; 24 July.

64 Usselincx, Argonautica Gustaviana, pp. 43–51.

65 Van Groesen, Amsterdam’s Atlantic, pp. 87–8.

66 Relationis Historicae Semestralis Continuatio: Jacobi Franci Historische Beschreibung aller denckwürdigen Geschichten (Frankfurt: Latomus, 1633), pp. 6–15: ‘Newe Schiffarth nach den Ost- und West Indien/ und andern frembden Landen von I. Köngl. May. zu Schweden angerichtet’; 15–18: ‘Erweiterung der Privilegii über die Newe Schiffarth nach beyden Indien’; pp. 18–20: ‘Vornembste Ursachen/ warum die Newe Suder Compagny in Teutschland anzustellen.’

67 Lichtenberg, Willem Usselinx, p. 178.

68 ‘15. Ocbtr. hatt die Pfalzgräfin einen jungen Prinzen geboren, hat nun 6 Söhne vnd 2 Töchter. / Tilli hat sein Hauptquartier vnd soll sein Volk nun zur Hülfe zum Spinola ins Niederland ziehn. / Der Herr von Dortt ist in Westindia vor der Festung … [sic] von einem Indianer mit 1 Pfeil vor den Kopf geschossen, davon er todt geblieben’ (Estorf, Diarium, p. 35).

69 Rößlin, 1624, 23 Oct. (Amsterdam, 13 Oct.): ‘Der Herr von Dordt ist in Brasilien, als er das Castel … [sic] hat besichtigen wollen, ob es nöhtig zu bewähren, oder abzubrechen, von den Indianern, mit einem Pfeil durch den Kopff geschossen, und todt bliben.’ The handwritten editorial comments on Röslin’s newspaper were added by Württemberg court secretary and archivist Johann Jacob Gabelkover; see Weber, ‘Kontrollmechanismen im deutschen Zeitungswesen’, p. 66.

70 Both known examples, the Ausländischer Potentaten Krieges- und Stats-Beschreibung, focussing exclusively on Asia, and the Türckischer Estats- und Krieges-Bericht, which only brought Ottoman news, appeared in the Hamburg publishing house of Thomas von Wiering. See also J. Hillgärtner, ‘Die erste illustrierte deutsche Zeitung? Thomas von Wierings Türckischer Estats- und Krieges-Bericht’, in S. Geise et al., (eds) Historische Perspektiven auf den Iconic Turn: die Entwicklung der öffentlichen visuellen Kommunikation (Cologne, 2016), pp. 96–114.

71 For a discussion of empire-dominated approaches to early modern globalization, see A. Strathern, ‘Global Early Modernity and the Problem of What Came Before’, in C. Holmes and N. Standen (eds), The Global Middle Ages, supplement 13, Past & Present (2018), pp. 317–44, here p. 340.

72 On strategies of information management and overseas news in the Spanish Empire, see C. Borreguero Beltrán, ‘Philip of Spain: The Spider´s Web of News and Information’, in B. Dooley (ed.), The Dissemination of News and the Emergence of Contemporaneity in Early Modern Europe (Farnham, 2010), pp. 23–50; D. Rault, ‘La información y su manipulación en las relaciones de sucesos. Encuesta sobre dos relatos de batallas navales entre españoles y holandeses (1638)’, Criticón, 86 (2002), pp. 97–116.

73 S. Conrad, What Is Global History? (Princeton, 2016), pp. 73–80.

74 See Dooley, Emergence of Contemporaneity. Curiously, engagements with non-European news are virtually absent from this volume.

Autore: Johannes Müller

Fonte: Academia.edu

Categorie

Tag

Lascia un commento