To begin with, during the era of the Republic in Rome itself and other large cities, there were many workshops that produced weapons and armor. It was they who supplied the army, which was initially quite small – two legions and a few more turm cavalry, moreover, most often recruited from the allies. Everything changed with the beginning of the Principate, when the center of arms production moved from Rome to the outskirts of the state. A large number of small and medium-sized workshops were now operating here, located in many, if not all, permanent military camps. Well, state workshops were opened by the end of the IIIrd century throughout the empire. The scale of the work of such real arsenals was larger than that of the old local workshops, since they had to serve the needs of vast territories; some of them specialized, which undoubtedly allowed them to supply large quantities of uniform weapons when needed. In fact, only one Latin writer, a contemporary of Diocletian, Lactantius, whose text was no doubt copied in the sixth century by the Byzantine chronicler Malalas, indicated that all these innovations were carried out by this particular emperor.

Some arsenals may have functioned earlier, but since the second half of the third century they have increased significantly. These were already real factories with a division of labor and a wide use of “machines” (for example, water-lifting, mechanical hammers, etc.) and the simplest mechanisms. The factories in Aquincum, Carnuntum, and Lauriacum did not seem to have started from scratch, but developed from pre-existing workshops in legionary camps in various locations. But their heyday, so to speak, came from the second half of the IIIrd century A.D

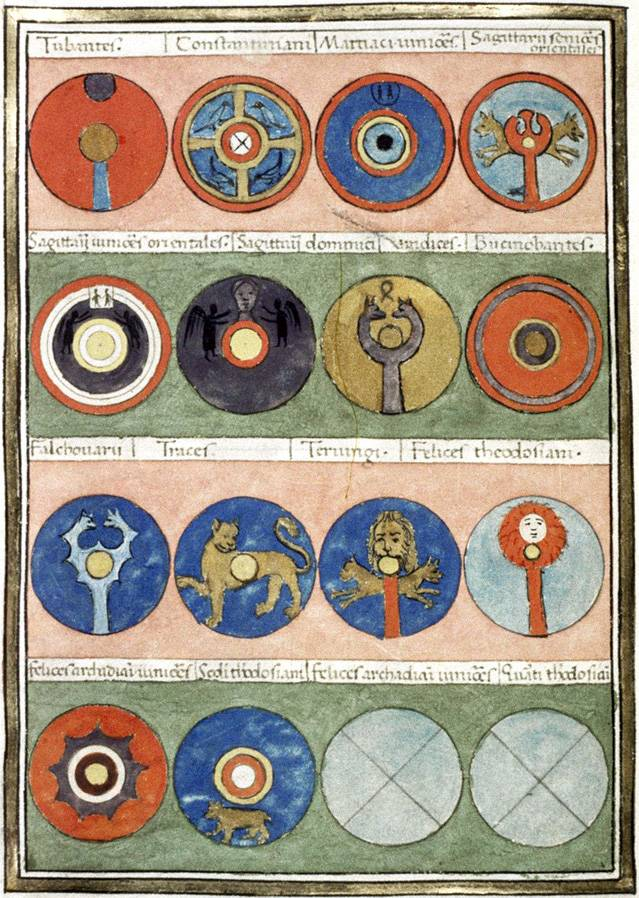

A page of a medieval copy of the Notitia Dignitatum depicting the shields of the Magister Militum Praesentalis II, from a list of Roman military units

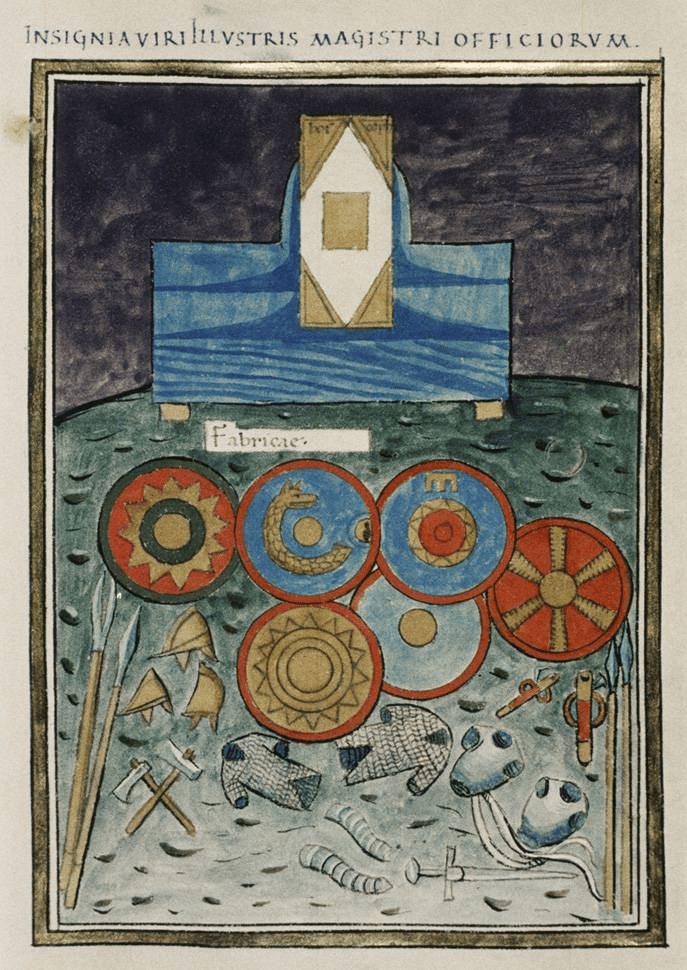

The best documentary source on the new system of manning the army is the official document describing the economic and administrative organization of the late empire – Notitia Dignitatum. Modified during the IVth century and compiled at the beginning of the Vth century and later (chapter XI (East) and chapter IX (West)), they list about forty different large enterprises and almost always what they produce. If we add to this information information gleaned from other sources (secondary texts, inscriptions), we get the following list:

Shields – Augustodunum and Aquincum Kamuntum, Lauriacum Cremona, Marg’s arsenal (in Illyria);

Shields, swords – Amiens;

Shields, saddle covers and various weapons – Sirmium;

Shields and other weapons – Antioch, Damas, Edessa, Nicomedia, Sardis (in Lydia), Adrianopolis Marcianopolis, Verona;

Armor – Loriki – Mantua;

Armor – Klibanari (heavily armed horsemen) – Augustodunum, Antioch, Caesarea of Cappadocia, Nicomedia;

Swords – Luke and Reims;

Spears – Irenopolis in Cilicia;

Luke – Titinum (Pavia);

Arrows – Concordia, Matisko;

Artillery — Trier, Augustodunum;

And other weapons – Thessalonica, Naiss, Ratiaria, Salon, Argentomagus (Argenton-sur-Croesus, Susions, Ravenna (?)), Constantinople (since the time of Justinian)

The location of these factories was not chosen by chance. Some of them were already known for their local raw materials and skilled labor, and some were located at a safe distance from the border and still had good connections with both border camps and Rome. Other factories undoubtedly arose out of the workshops already held by the legion. Danube factories are an example of this. The main question, however, will be: what was the reason for such a reorganization under Diocletian? Why was the semi-autonomous organization, with each legion receiving weapons either from their own workshops or from local civilian craftsmen, replaced by an extensive industrial network throughout the empire?

Historians, writes Michel Fegere, were initially surprised that the Roman state suddenly needed to create workshops, although the previous system worked very well until the middle of the IIIrd century. The commissioning of new factories should reflect the specific needs of society, right? The reason, according to a number of historians, could be that the entire provincial society of the IIIrd century was already very disorganized and that such changes were vital. Many craftsmen in both civilian and military workshops lost their jobs, and small workshops located in camps along the Rhine and Danube, as well as on the Euphrates, could no longer guarantee production and even the safety of their warehouses, which could fall into the hands of the enemy. Moreover, the collapse of the monetary system due to successive devaluations made private investment impossible, even in areas far from war zones. In short, the needs of the army had to be met at any cost, and only the state could plug the resulting “gap”. It is possible that the nationalization of production centers carried out by Diocletian with their subsequent consolidation was only a formal recognition of the current state of affairs caused by the difficult situation in the provinces.

Although the imperial arms factories and mints were staffed mainly by slaves, their labor was not dominant, and factory workers enjoyed privileges. Free people were hired there like militia in the army, and had the same status with them, and the years spent in factories were counted as years of military service. There is no doubt that many of these workers were simply transferred from the workshops of the legionnaires to the imperial workshops. However, despite the status of workers, the nationalized workshops could not maintain the high standards of past centuries when it came to the production of often complex and sometimes fragile and beautifully decorated items: especially cavalry helmets.

While examples from the mid-IIIrd century still show great craftsmanship, helmets from the early IVth century become strictly functional industrial pieces. Previous helmets had a one-piece forged bowl; the new ones began to represent two hemispheres riveted along the seam, and these hemispheres themselves could now consist of only three triangular plates fastened with rivets. It seems clear that these new helmets reflect new manufacturing methods and can be manufactured faster and in significantly larger quantities than previous designs. Moreover, their manufacture did not require skilled labor. So the increase in the number of troops under the command of Diocletian led to a significant simplification of the protective Roman weapons.

Surprisingly, at the same time, abundantly decorated helmets appeared, for example, a helmet made of iron plates covered with gilded silver leaf, discovered in 1910 in Dörna (North Brabant). The embossed decor and silver rivets create an impression of luxury and good taste, and besides, it has two inscriptions, one of which mentions a certain M. Titius Lunamis, whose name is followed by the weight. Perhaps this is the name of the controller responsible for checking the amount of silver used in the construction of this helmet. Did such a helmet come out of the walls of the new factory? Or was it custom-made by a gunsmith in the Legion’s workshop? Unknown.

A Roman helmet (sometimes called the “Luxurious Helmet”), found during excavations at Berkasovo in Serbia. Consists of four parts, 3 mm thick and plated with 2 mm gilded silver. The helmet is adorned with large imitations of precious stones: emerald, onyx, chalcedony – in fact, the stones are made of glass paste. The helmet is decorated with chased patterns and silver rivets. There is an inscription in Greek above the left protective cheek plate (the Roman elite used Greek, which indicates the high status of the owner): “Dizzon, wear it in good health. Made by Avitus”. Judging by the name, the owner of the helmet was from Dacia or Illyria. Vojvodina Museum, Novi Sad, Serbia

The Romans called chain mail lorica hamata, and they made it from iron rings (flat or round), called khami, intertwined in various ways and having an outer diameter of 3 to 10 mm. Lorica could have anywhere from 10 to 000 rings; some of them, according to the finds, could be tinned or gilded. The weight ranged from 30 to 000 kg. The rings of early chain mail were usually pulled together. But it was easy to fix them! But some lorics had welded rings interspersed with riveted khami – a rather rare manufacturing option for Rome.

Another graffito, STABLESIA.VI., Is associated with Legion VI mentioned in Notitia Dignitatum. Other finds, such as “helmets from Berkasovo,” Budapest, present the problem of how military production was organized during this period. It is hard to believe that highly skilled craftsmen did not continue to work in the army into the 476, even though the bulk of the products were now produced in factories. In Gaul, the factory system probably did not survive the fall of the empire i. But in the East (as well as in Italy in a modified form), a number of different legal sources prove that state arsenals not only continued to exist, but also expanded, at least until the VIth century.

Beyond helmets, the impact of the new system on various weapons is not easy to see. In addition, not all weapons production was carried out in a factory way. Bows and arrows, for example, were produced by the only bow manufacturer listed in the Notitia Dignitatum was in Ticinum in northern Italy, while arrows were made in Macon and Concordia. Obviously, the needs of the Dacian, Persian and Numidian archers were met by local suppliers, so these local archers did not need a state factory. Yes, its power would simply not be enough for all of them!

It seems that body armor was used much less frequently in the IVth century, which is why the historian Vegetius complains about the risk that infantrymen are exposed to, unprotected from arrows and attacks of opponents. However, it echoes a popular literary cliché at the time, as writers of the time often and nostalgically recalled the bravery, skill and high training of ancient armies. It is difficult, however, to agree that in the IVth century the Roman soldiers completely abandoned such weapons. Several archaeological finds show that chain mail, in particular, was still used in the IVth century. And its reappearance at the beginning of the Middle Ages shows quite clearly that it did not disappear completely from the military tradition, even if its use in the Late Empire was not as widespread as in the early Principate.

Vegetius informs us that the shield resembled its predecessors, and that it was covered with monotonous symbols of cohorts and legions. Attempts were made to identify military units from the illustrations in Notitia, but careful examination showed that its scribe was clearly tired as the work progressed, and his images could not be used for this purpose. Although you can get a general impression of the drawings on the shields. In terms of physical characteristics, the fourth century shield, even for infantry, was larger than previous versions, and had an oval or even circular shape, judging by modern memorials and paintings.

As for swords, 20 burials in northern Gaul have been found to contain spatha specimens typical of this period. Partially descended from the Lauriacum type, they were 70-90 cm long and have a wider blade (5-6 cm) than their predecessors. In this way, their designs came closer and closer to the design of the Merovingian swords, which followed them. Since the end of the XNUMXth century, there has been a damaging of the blades, which ultimately increased the reputation of the weapon of the Middle Ages. The handles, well preserved in the Scandinavian swamps, may be wood, cattle bone, or ivory, and are always three-piece with a threaded shank. The central part of the handle is straight (often grooved laterally), the guard is usually a simple oval plate.

A new type of sword appears next to the Germanic one, which has a rounded edge, and can be clearly seen on sculptures: for example, in the depiction of swords by the Tetrarchs in Venice; and on the tombstone of Lepontius in Strasbourg. The rectangular end of the scabbard is simply bound with metal. It is clear that this new system greatly simplified the manufacture of the scabbard, and perhaps it was an innovation in factories. Likewise, it can be noted that the attachments for hanging the scabbard, although similar to the old models, have a simplified design.

The nibs have become larger in size, but are now more difficult to classify than previous designs, with the exception of the “winged point” nib, which developed impressively in the early Middle Ages. First appearing in Gaul in the IIInd century as a hunting weapon, it was adopted by the army at the end of the IVth century.

“Artillery”, that is, throwing machines, after the innovations of the Dacian wars, developed very slowly in Rome. And what was the point of developing it, when every conceivable perfection within the framework of the then level of technology was achieved? True, apparently, there was a general tendency to simplify and facilitate the use of these weapons. However, the finds show that the throwing machines of that time are not much different from the earlier ones. Here we see one of those rare cases – admittedly of very limited significance due to the specific nature of this weapon itself, when, outside the general tendency of simplification, some of its samples continued to be manufactured exclusively by highly qualified craftsmen, and factories did not try to change its design in order to increase the scale its production.

Autore: Vyacheslav Shpakovsky

Fonte: Topwar.ru

Lascia un commento