The Special Operations Executive (SOE) in Singapore-Malaya during the Pacific War has consistently been a focal point of scholarly attention. In the existing academic and literary spheres, there is a plethora of research and retrospective works on SOE, which can be viewed from three perspectives.

The first perspective focuses on the cooperation between the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and SOE, utilising memoirs and other materials from MCP affiliates. The second perspective is from the Western angle, where studies primarily utilise British archives and oral sources to discuss the organisation of SOE by the British and through the works of scholars such as Charles Cruickshank (1983) and Douglas Ford (2006). The third perspective is from the KMT angle, where works primarily utilise KMT archives to reconstruct the collaboration between the KMT and SOE. Examples include the works of Ma Zhendu & Qiu Jin (2006) and Y. X. Chen (2019).

Certainly, in addition to these three perspectives, some scholars have focused on significant Chinese participants within SOE, such as Lim Bo Seng and Chuang Hui Tsuan (Tang, 2014; Wong, 2022). Overall, these studies have made significant contributions to the understanding of SOE and its activities in Singapore-Malaya during the Pacific War. However, compared to studies from the perspectives of the MCP and the Western angle, research on SOE from the KMT perspective remains relatively scarce, with many historical details still unclear. In light of this, this article will utilise archival materials collected by the KMT, combined with British HS series archives. Building upon existing research, the aim is to further clarify the collaboration between KMT agencies and SOE.

Establishment of SOE and the Oriental Mission in Singapore-Malaya

In July 1940, Britain decided to establish an organisation to conduct Resistance Movements in response to the needs of the European battlefield, recruiting personnel from occupied or soon-to-be-occupied countries by the enemy. These recruits would infiltrate occupied areas to harass the enemy and coordinate actions when the Allied forces launched attacks with the ultimate aim to annihilate the enemy. Formed in July 1940, the SOE was a subordinate unit of the Ministry of Economic Warfare, which was to implement economic blockades against the European continent. The operational tasks of the SOE were directly issued from London, not by the commanders on the battlefield. However, the SOE in each theatre of operations would coordinate with the military commanders on the battlefield. The SOE was initially composed of three organisations: the first was Section D established by Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) in 1938, responsible for sabotage and investigation activities in enemy territory; the second was Military Intelligence (Research) (MI(R)), established by the War Office in November 1938, and responsible for guerrilla training and research; and the third was the Propaganda Department located in Electra House, which operated under the Foreign Office (Kenneison, 2019).

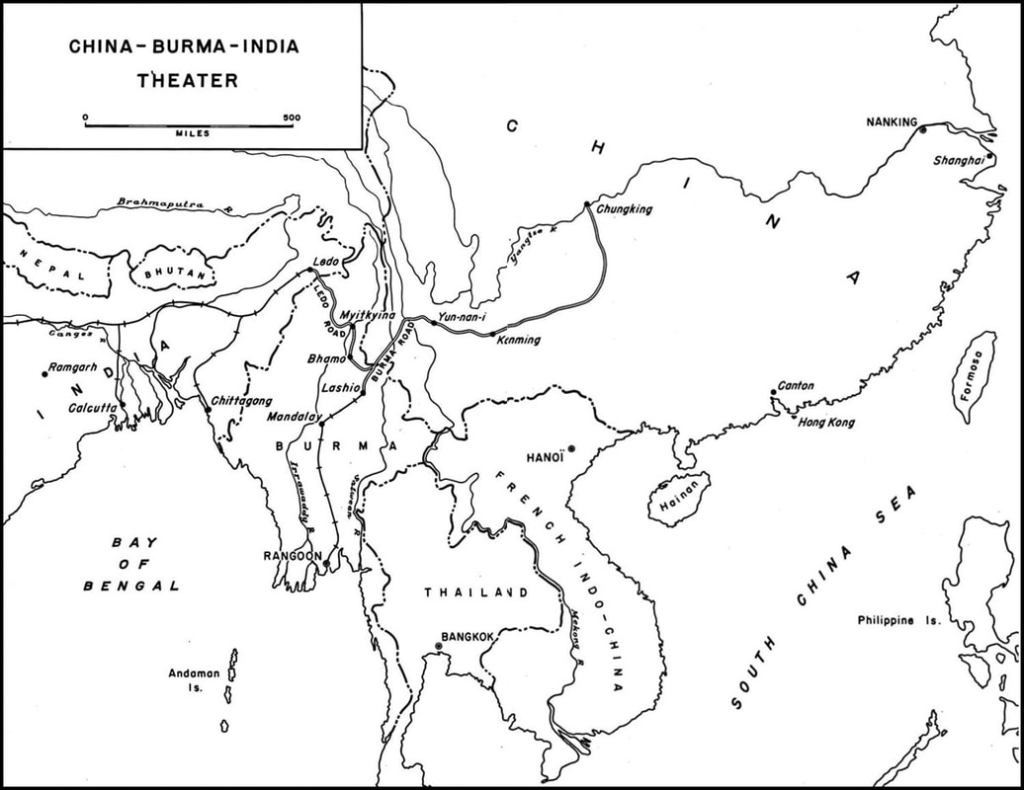

During the Second World War, “Europe First” was consistently regarded as Britain’s primary strategic principle, which was also manifested in the activities of the SOE. Asia remained on a lower priority order in the SOE’s operational objectives. With Japan’s frequent military activities in Indochina, the British Ministry of Economic Warfare considered launching the Oriental Mission in Burma, Siam, the Indochina Peninsula, Singapore, Malaya, Hong Kong, and coastal areas of China. On 26 November 1940, the British Cabinet agreed to operate in Asia in the form of the SOE. On 24 January 1941, the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Shenton Thomas, was formally notified that the SOE’s Oriental Mission would be established under the command of the Far East Command. Lieutenant Colonel St. J. Killery and his deputy, Basil Goodfellow, arrived in Singapore between April and May 1941 to commence the Oriental Mission. In February 1941, Killery recruited young officer Captain Jim M. L. Gavin to participate in the mission. To ensure safety and secrecy, Killery disguised himself in civilian clothing to conceal his military identity. In mid-1941, with the assistance of his deputy Goodfellow, Major Killery established a special training school called the “No. 101 Special Training School” (101 STS) on a piece of land at Tanjong Balai on the western coast of Singapore (Shennan, 2007). This school was specifically designed to train personnel for guerrilla warfare, intelligence gathering, and sabotage activities behind enemy lines. The 101 STS had a total staff of approximately 150 persons, divided into three groups: Administrative Group, Recruitment and Liaison Group, and Regional Group. At that time, 101 STS was the earliest secret training school established outside of the British. The school’s curriculum included training in small arms, explosives, communication equipment usage, and boat handling. Personnel from the Oriental Mission across various Asian locations were assigned to this school for training. The trainees were categorised into two groups based on regions: the Burma/China group led by Steve Cummins and the Siam/Indochina group commanded by Spenser Chapman.

In August 1941, the Oriental Mission devised plans for guerrilla operations in the event of the fall of the Malay Peninsula, but these were dismissed by the Far East Command, the British government, and the Straits Settlements government, deeming them impractical and unnecessary (The National Archives of (U. K.) May 1941-March 1942). The prevailing belief at the time anticipated Japanese invasions in Indochina and the Dutch East Indies, while official stance held that Malaya was safe from attack by relying on Britain’s naval and air power to deter Japan, and assuming that Japanese aircrafts from Indochina would not reach Malaya on bombing missions. Thus, the Oriental Mission was instructed in early 1941 that no preparations were warranted in Malaya. Goodfellow and associates were cautioned that any readiness for resistance in Malaya might incite civilian panic, signalling imminent war. Moreover, the British colonial administration opposed arming and training the Chinese populace, citing distrust of the Chinese (Kenneison, 2019).

Japan’s surprise attack on 8 December, 1941, prompted a shift in strategy. British military and political leaders, faced with Japan’s formidable offensive, overcame their distrust of the Chinese. Shenton Thomas, the Governor of the Straits Settlements, and Percival, the British Commander-in-Chief of Malaya, who had long opposed training the Chinese, ceased their objections (Kenneison, 2019).

The British SOE Choice of Partners

When the British SOE decided to collaborate with the Chinese, it was members of the MCP who were selected to undergo training at 101 STS, rather than the KMT, which had established cooperation eight months ago. In early 1941, given the critical international situation, SOE dispatched G. Findlay Andrew to Chongqing to advance matters concerning intelligence cooperation with the KMT, and engage with Wang Puhng-Shung [王芃生], the head of the Institute of International Relations (IIR) (Aldrich, 2000). In mid-April 1941, Chiang Kai-shek approved the cooperation between IIR and SOE on Japanese intelligence, leading to the establishment of the Research and Investment Institute (RII) headquartered in Chongqing. This institute established an intelligence network covering Northeast China, South China, North China, Southwest China, extending to Korea, Indochina, and Rangoon, Burma. This marked the beginning of intelligence cooperation between the KMT and SOE (The National Archives (U. K.), 15 October, 1942)

Following this, in August 1941, SOE collaborated with the Chinese intelligence organisation Bureau of Investigation and Statistics (BIS) [军统] to establish a China Commando Group aimed at conducting sabotage operations in enemy-occupied areas of China (Academia Historica in Taipei, 16 December, 1941,). However, intelligence cooperation between the KMT and SOE did not extend to Singapore-Malaya, though it had in fact a vast intelligence network in these territories. According to Tan Chee Seng (2005), before the Pacific War, the BIS had already established a substantial intelligence network in Malaya-Singapore, with approximately 200 intelligence officers and radio stations in place. The activities of these personnel in Singapore-Malaya were conducted covertly, with public professions serving as cover. Even after collaborating with SOE on the Chinese mainland in April and August 1941, they kept their intelligence network in Singapore-Malaya under wraps (Tan, 2005). Given the KMT’s strict confidentiality regarding its intelligence network in the Singapore-Malaya, along with the urgency brought about by the Japanese invasion, the MCP became the collaborator of choice for SOE in the Malaya-Singapore. On the side of the MCP, they also adjusted their longstanding anti-British stance. At that time, the MCP lacked experience in leading wars, military cadres, and weapons. Therefore, they accepted the proposal advocated by the prominent overseas Chinese leader Tan Kah Kee to unite Malaya against Japan and jointly resist the Japanese with the British (Malayan Communist School, 1985). On 17 December, 1941, during the second meeting of the Central Executive Committee of the Seventh Expanded Central Committee of the MCP, a resolution was passed that stated: “The initiation of adventurous wars by international fascism poses a serious threat to human survival.” Therefore, one of the party’s main tasks was to “unite and mobilize all forces to become the support of the British government and overthrow Japanese fascism” (Malayan Communist Party, 17 December, 1941).

In order to cooperate with MCP, the British decided to release all political prisoners associated with the party and recruited 165 members of the MCP for training at the 101 STS and then deployed them to conduct disruptive activities behind enemy lines (Hara, 2006; Kenneison, 2019). The objective was to delay the advance of Japanese forces by two to three weeks, allowing the British to fortify their defences (Chin, 2004). The MCP’s Chinese trainees were organised into four groups: the first batch comprised 15 individuals from Singapore, the second included 30 from Perak and Singapore, the third consisted of 60 from Selangor, Perak, Pahang, and Singapore, while the fourth recruited 60 from Johor and Singapore (Quek, 1999). Initially, the first batch intended to operate in northern Malaya, but upon reaching Serendah north of Kuala Lumpur and facing the rapid fall of Kuala Lumpur, they established themselves there with support from local Communist organisations. More than 100 individuals were formed into the officially established First Independent Brigade of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army in early January 1942. However, the growing intensity of the war frustrated the attempts of the other three batches to reach their planned destinations. The second batch managed to reach Negeri Sembilan, the third batch made it to the northern part of Johor, and the fourth batch stopped in southern Johor. Notwithstanding their efforts, the Oriental Mission struggled to impede the Japanese forces following the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941. Although the leaders of the 101 STS and the trained Chinese personnel established rear bases in the forests in Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Johor, and other areas, the mission was ultimately disbanded due to communication loss with its London headquarters. Consequently, British personnel associated with the mission gradually withdrew from Singapore-Malaya (Cruickshank, 1983).

Cooperation between the KMT and SOE

In January 1942, British personnel from the SOE Oriental Mission evacuated from Singapore, with some relocating to India, others to Burma, a few to China, and a handful to Java (The National Archives (U. K.), May 1941-March 1942). Those retreating to India formed a larger entity known as Force 136. This designation emerged officially emerged in March 1944, though its precursor was the Southeast Asian branch of the SOE, including the Malaya Branch. Before the formal establishment of Force 136, Goodfellow and others who retreated to India were dissatisfied with the failure of the Oriental Mission. In July 1942, they relaunched the “Indian mission,” with most of the participants from the original Oriental Mission joining the Indian Mission instead. The Indian Mission was divided into two parts: one aimed to prevent Japanese spies from infiltrating India, while the other was to utilise Dutch submarines to attack enemy warships and merchant vessels in the Malacca Strait. The establishment of Force 136 had received assistance from the Royal Dutch Navy and Air Force (Trenowden, 1983).

Under Goodfellow’s leadership, British colonial police officer John Davis [1] John Davis was born in Sutton in 1911. At the end of 1930, he embarked on a journey that led him to connect with Malaya. He was selected as a probationer in a group of ten young men to serve in the Federated Malay States and the Straits Settlements Police. Following six months of training in Kuala Lumpur and temporary assignments in Selangor, John’s career began in earnest in February 1932. In December 1940, upon receiving notice of his transfer from the Federated Malay States Police Service, he was reassigned to the Straits Settlements Police. In July 1941, he was scheduled for transfer to the Special Branch. In May 1941, John Davis embarked on his journey with the Oriental Mission(Shennan, 2007, pp. 7-8, 24).] and civil administrator Richard Broome, who had previously participated in the Oriental Mission in Singapore, also rejoined the Indian Mission. John Davis was appointed as the head of the Malaya Branch. Their plan was to use Dutch submarines to transport personnel into Malaya for gathering intelligence behind enemy lines and establishing contact with local anti-Japanese forces in preparation for counterattacks in Singapore-Malaya.

At that time, there were mainly two anti-Japanese armed forces active in Singapore-Malaya: one was the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army led by the MCP, and the other was the Overseas Chinese Anti-Japanese Army formed by members of the KMT and Chinese Freemasons guerrilla units (Shin Min Daily News, 5 October, 1994). Due to the attention drawn by Western faces and the language barrier with the local Chinese community, they hoped to cooperate with KMT for intelligence purposes, sending Chinese agents to conduct operations behind enemy lines in Singapore-Malaya.[2] The British were willing to cover all expenses, while China only needed to provide personnel (KMT Party History Museum, September 1942).

In September 1942, Lim Bo Seng, who served as the Chief Administrative Officer of the Chinese Seamen’s Wartime Service Corps in India,[3] received a visit from Goodfellow. Goodfellow instructed Lim Bo Seng to convey to the KMT leaders that Britain intended to collaborate with China on intelligence work in Malaya.[4] Before the fall of Singapore, Lim Bo Seng was a prominent patriotic overseas Chinese figure in Singapore-Malaya. Before the Pacific War, he had participated extensively in anti-Japanese patriotic movements in the region. After the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937, Lim Bo Seng orchestrated the “non-cooperation movement,” encouraging workers at Japanese-operated mines in Singapore-Malaya to go on strike (Wong, 2022). Moreover, when Japan attacked Singapore and Malaya, Lim Bo Seng actively rallied Chinese organisations to form volunteer forces to assist the British Army in combat (Shin Min Daily News, 29 August, 1996).

Goodfellow had hoped that Lim Bo Seng could convey the British side’s cooperation request to the KMT. Subsequently, Lim Bo Seng conveyed the British cooperation intention to Wu Tieh-ch’eng [吴铁城], the Minister of the Overseas Department of the KMT. Wu agreed and telegraphed Central Bureau of Investigation and Statistics (CBIS) Director Hsu En-tseng [徐恩增] to draft a cooperation plan (KMT Party History Museum, 10 and 18 September, 1942). In September 1942, the Overseas Department of the KMT dispatched Li Hung-ming [李鸿鸣] to hold consultations on KMT-British intelligence cooperation. On October 4th, Li Hung-ming and Goodfellow initiated negotiations regarding intelligence cooperation in Malaya. After negotiation, Li and Goodfellow agreed to conduct intelligence cooperation in the Singapore-Malaysia, with KMT providing personnel and the British providing funds and supplies (KMT Party History Museum, 4 October, 1942).

Recruitment and Training of Kuomintang Agents

In July 1942, alongside the establishment of missions in India, the SOE set up a Guerrilla Training Unit at Kharakvasla in Poona, India, to train personnel for behind-the-enemy-lines operations. With the priority of gathering intelligence from the Far East occupied areas, the guerrilla training department was reorganised into the Eastern Warfare School (India), serving as a base for selecting personnel for Far Eastern behind-the-enemy-lines operations.

In May 1943, the British established the School for Eastern Interpreters near River Hooghli in Calcutta, providing a six-week course in intelligence, telecommunications, reconnaissance, propaganda, and other subjects. Additionally, the Royal Air Force established the Air Landing School for parachute training near Chakala in northern India, close to Rawalpindi. The Advanced Operation School was established in Trincomalee, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), offering courses similar to those at the Far East War School’s Indian campus. Trincomalee was also the location of a British submarine base. As for signal training, initially overseen by the Chief Signals Officer in Meerut, northeast of Delhi, new telegraphists were required to undergo a four-month basic telegraphy course at the Advanced Operation School and Eastern Warfare School (India). Meerut served as the radio practice ground (Cruickshank, 1983).

After the signing of the Kuoomintang-British intelligence cooperation agreement in October 1942, Lim Bo Seng left the Chinese Seamen’s Wartime Service Corps in India and returned to Chongqing to prepare for the upcoming intelligence cooperation between China and Britain. At Lim Bo Seng’s arrangement, Singaporean overseas Chinese and Vice-Chief Administrative Officer of the Chinese Seamen’s Wartime Service Corps in India, Chuang Hui Tsuan [庄惠泉], were also transferred to work in the SOE’S Malaya Branch. Lim Bo Seng was initially responsible for recruiting agents, and later Chuang took over when Lim Bo Seng departed on a different mission. Priority was given to selecting overseas Chinese students returning from Southeast Asia.

The Malaya Branch originally had five Malayan Chinese recruited by the British. In January 1943, Lim Bo Seng led the first batch of Malayan personnel recruited from China to India. They were sent to the guerrilla training department in Poona, arranged by the British, for training, which later became the Advanced Operation School and Eastern Warfare School (India). Lim Bo Seng stated in his report to Wu Tieh-ch’eng that the number of students at the Advanced Operation School and Eastern Warfare School (India) exceeded 1,000, including personnel from China, Britain, Arabia, Persia, Afghanistan, Burma, Siam, Annam, and the Dutch East Indies. After their training, these students would be dispatched to various locations in the Far East and the Middle East to engage in behind-the-enemy-lines operations. The students at the school were divided into classes based on nationality or ethnicity, and classrooms were kept far apart to prevent any horizontal relationships between students (KMT Party History Museum, 20 March, 1943).

The first batch of students recruited by Lim Bo Seng from China (code-named “Dragon One”) underwent joint training with the five Malaya Chinese recruited by the British. The Chinese class instructor was F. W. Kendall, a Canadian who had previously been involved in intelligence work in Hong Kong. After the fall of Hong Kong on 25 December, 1941, Kendall escaped with Chan Chak, the head of the KMT’s branch in Hong Kong. [5]In addition to Kendall, there were seven other British instructors in the class. Lim Bo Seng was responsible for translation, while also serving as the liaison officer and the leader on the KMT side. The school’s curriculum included physical fitness, organisation of the Fifth Column, clandestine communication, intelligence, assassination, guerrilla warfare, arson, and explosive techniques. The daily schedule was very tight, with study time from 7:30 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. Apart from mealtimes and short breaks, the rest of the time was spent in classes and field exercises. As for the allowance of Chinese personnel, during the training period, the British side provided meals, clothing, and related items. Additionally, a monthly allowance was provided, with 300 dongs for district chiefs, 200 dongs for deputy district chiefs and telegraph operators, and 150 dongs for other personnel. When departing for tasks in Malaya, besides allowances, the British would also give special fees at their discretion, and those with excellent performance might receive bonuses (KMT Party History Museum, March 1943).

Not all trainees recruited by KMT underwent the same training. In addition to general guerrilla warfare training behind enemy lines, a specialised radio unit was also established specifically for training in radio communication. In January 1943, Dragon One trainees such as Tham Sien Yen [ 谭显炎], Wu Chye Sin [吴在新], Loong Chiu Ying [龙朝英] and others, upon arriving in India, were assigned to undergo special agent training near Poona at Singarh. This training included tasks such as demolishing railways and bridges, ambushes and guerrilla tactics, night marches, disrupting enemy camps, using compasses and maps to infiltrate designated areas by boat, and gathering intelligence.

After completing the training course, Tham Sien Yen was arranged by the British to infiltrate major cities like Mumbai, where he assumed various roles on different occasions to gather intelligence and undertake secret courier missions, practising the various skills he had learned. Subsequently, the Dragon One trainees were transferred by the British to coastal areas to learn sailing and the techniques of operating two-person rubber landing craft. Meanwhile, radio trainees like Liang Yuan Ming [梁元明] and others went to the Meerut military camp near Delhi in February 1943 to receive training at the Signal School. After completing their training at the end of March, they returned to Poona for practical training. In May 1943, after completing a series of training sessions, Tham Sien Yen, Li Hakwong [李汉光], Loong Sow Ying, Wu Chye Sin, Ah Piu [阿彪] and the head of enemy operations in Malaya, John Davis, were transferred to Ceylon. From there, they boarded a Dutch submarine and infiltrated Malaya to carry out their missions (You, 2015).

The curriculum for each batch of trainees varied according to the actual circumstances. According to the recollection of Dragon Two trainee Chang Teh Cheok [张德爵], based on their understanding of the situation in Malaya and military affairs, and in accordance with the trainees’ backgrounds, British instructors adjusted the course duration and content. The curriculum included overviews of Japanese military weapons, military maps of the Malaya, Japanese communication methods, secrecy skills, intelligence gathering, and the use of weapons and explosives (Chang, 1984). Dragon Two trainees such as Chang Teh Cheok received consecutive military training and internships in various locations including Calcutta, Poona, and Ceylon. Subsequently, to adapt to the situation in Malaya, additional training such as parachuting, receiving airdropped supplies, and advanced communication skills were added to the curriculum for later batches of trainees.

Additionally, the British arranged for trainees to go on educational outings. Dragon Three trainee Chen Yi Yue [陈义育] recalled that the 21 trainees of his batch, while traveling from Calcutta to Ceylon, were arranged to visit airports, munitions factories, steel mills, and weapon repair factories to broaden their knowledge. (Chen, 1984).

The Construction and Demise of the Intelligence Network

The “Dragon Group” agents, who entered Malaya via Dutch submarines, not only made contact with the MCP but also established an intelligence network locally. The process of establishing an intelligence network by KMT agents is as follows: After landing, Dragon One member Loong Sow Ying, under Davis’s command, began establishing an intelligence network in Lumut, Perak. Loong Chiu Ying began to work in a fellow Hainanese’s coffee stall. With the help of the stall owner, Loong Chiu Ying obtained identification documents (Chapman, 1963). With the help of the coffee stall owner, Loong Chiu Ying rented a stall in Lumut to sell cigarettes and fruits, serving as a liaison point. Wu Chye Sin, also a member of Dragon One,” was employed by local Chinese to plant after descending from the mountains. Shortly after, Wu Chye Sin met the manager of a local paper established by the Japanese. Born into a wealthy business family in Guangzhou, Wu Chye Sin utilised his business acumen to swiftly establish a business network in Lumut and befriended Japanese officers. With the assistance of these officers, Wu Chye Sin commenced importing and wholesaling Thai rice in Lumut through a franchising deal. Wu Chye Sin also befriended Chen Ji Non [郑菊农] in Ipoh. In collaboration with Chen, he opened the Jian Yik Jian Store in Ipoh. With this, KMT Agents had also established an intelligence point in Ipoh. Meanwhile, Wu Chye Sin handed over the rice import business in Lumut to Tan Chong Tee [陈崇智] (Chapman, 1963).

Li Hakwong established a maritime transportation line on the Island of Pangkor near Lumut, used for ferrying the landing personnel and equipment brought by submarines. Li Hakwong was a Chinese overseas immigrant in Singapore. During the resistance against the Japanese invasion, he was summoned to enter the KMT’s Central Military Academy for training and was later recruited by Lim Bo Seng into the Malaya Branch of Force 136. After infiltrating into Pangkor Island, and through a Chinese coffee shop owner, he met Chua Koon Eng [蔡群英] who ran a seafood and grocery business on the island. Li Hakwong used smuggling opium and gold as excuses to recruit Chua Koon Eng and promised if he provided the boats, he would receive a third of the profits from smuggling operation. With the boat, along with two Hainanese boatmen, Li Hakwong was able to transport members of the Dragon Group until the middle of 1944 to help KMT agents to established an intelligence network (Chapman, 1963).

After establishing various intelligence stations, Tan Chong Tee served as the liaison between these stations. According to agreements, each time a Dutch submarine arrived, it would bring a sum of operational funds, possibly in U.S. dollars or gold. These funds were not to pass through the hands of the MCP but were to be directly transported to Ipoh and handed over to Wu Chye Sin for allocation. Tan Chong Tee’s primary task was to transport the supplies received from Li Hakwong on the submarine from Pangkor to Ipoh for delivery to Wu Chye Sin. To facilitate transportation, Tan Chong Tee collaborated with Loong Sow Ying and purchased a black Austin car from a second-hand car dealership. To ensure the safe transfer of intelligence and materials, a compartment was created in the floor and other modifications were made to the car.

Unfortunately, the intelligence network established by Chinese infiltrators in Malaya was soon destroyed by the Japanese military police known as Kempeitai. Since 15 February, 1942, after Japan occupied Singapore, the Kempeitai became highly vigilant towards potential espionage activities that might be conducted by the British following their defeat. On 24 February, 1942, the Japanese-sponsored Zhao Nan Ri Bao” [昭南日报] warned that anyone who collaborated with the British or Chongqing government, whether by spying on Japanese military intelligence or carrying out actions favourable to the enemy of the Japanese army, shall all be considered as targets for execution (Zhao Nan Ri Bao, 24 February, 1942). The Kempeitai in Singapore (also known as the Onishi.

Kuomintang Agents and British SOE in Singapore-Malaya

Detachment) was under the jurisdiction of the Legal Affairs Department of the Japanese Southern Expeditionary Army, with its headquarters located at the current site of the National University of Singapore. It had jurisdiction over all Japanese military police in the Singapore-Malaya region, with the captain holding the rank of lieutenant colonel and subordinates were military officers holding the rank of lieutenant. The Kempeitai was commanded by Ōnishi Satoru, mainly to deal with communists, insurgents, and anti-Japanese elements in Singapore-Malaya (Hsu, & Chua,, 1984). The Onishi Detachment was established in May 1942 with approximately 53 members, including 4 officers, 49 soldiers, as well as several translators and local ethnic informants. At its peak, the Detachment comprised 71 members.[6]

The Onishi Detachment was mainly divided into two parts: operational and logistics. The operational group was further divided into the intelligence collection unit and the arrest investigation unit, while the logistics group consisted of the administrative unit and the legal affairs unit. The arrest and investigation units were the largest within the military police force, with up to 9 squads at its peak. Each squad consisted of two to three Japanese military police officers, led by a sergeant. During the Japanese Occupation, the Japanese authorities would employ local Chinese as translators and informants (The National Archives of Malaysia, 17 February, 1945). The primary task of local agents was to infiltrate the civilian population and gather intelligence. Until January 1943, several squads from the Onishi Detachment had been dispatched to various regions in Malaya, mainly to Kota Tinggi, Kulai, Kluang, Muar, and Segamat in Johor. Due to limited actionable intelligence, Onishi Satoru’s first action was to search for records of anti-Japanese activists maintained by the British in Malaya. Subsequently, they rounded up prominent members of the British police force and Special Branch detectives, which led to the discovery of several pre-Occupation anti-Japanese activists from Singapore. They persuaded these individuals to become double agents, including the Secretary-General of the MCP, Lai Teck (Choon, 1995).

In May 1943, when the KMT agents landed in Malaya, the Japanese immediately noticed them and began a secret investigation. The Japanese specifically brought in a counter-espionage unit from Singapore Kempeitai to deal with the landing KMT agents operatives. Leading the charge was Sergeant Major Ishibe Toshiro.[7] The Zhao Nan Shipyard in Pangkor Island was the location where Ishibe Toshiro monitored Tan Chong Tee and Li Hakwong. The initial intelligence for the Japanese came from Malays near Teluk Intan, who reported to the Japanese that armed British and Chinese forces were passing through at night, heading towards Ipoh. The Japanese then began intercepting them along the route, leading to encounters between the Japanese army and Davis and others along the route.

Later, the Kempeitai received reports that camps were set up on the hills of Segari, and rubber boats used by KMT agents landing personnel were also discovered. The various clues indicated that Allied agents were successfully landing in Malaya via submarines. The Kempeitai, by tracing the movements of KMT agents, deduced that their objective was to rendezvous with the MCP guerrillas operating in the Central Mountains, and therefore deployed agents for secret reconnaissance. The Kempeitai soon noticed the presence of KMT agents operating in Pangkor Island but refrained from immediate action against agents such as Li Hakwong and Tan Chong Tee. The purpose was to ascertain the Allied agents’ method of landing and spy network, with the ultimate aim of dismantling the KMT agents intelligence network.

After prolonged surveillance, the Kempeitai moved to arrest Loong Sow Ying, who was active in Pangkor, on March 22, 1944. However, Loong Sow Ying had already evacuated a day earlier and thus evaded arrest. Subsequently, Li Hakwong, who was also in, was captured. Likewise, Tan Chong Tee, Lim Bo Seng, Yu Tian Song, and Wu Chye Sin, who were active in the urban areas, were arrested. Only Li Hakwong managed to make his escape. Lim Bo Seng ultimately perished in the prison at Batu Gajah at the age of 35 (United Evening News, May 20, 1991). The harassment by the Kempeitai led to the disruption of the maritime communication channel between KMT agents and the headquarters of Force 136 in India.

Conclusion

Before the outbreak of the Pacific War, Britain’s misjudgement of the potential Japanese attack on Singapore-Malaya led to insufficient preparations by the SOE in the region. Although the KMT maintained an intelligence network of approximately 200 personnel in Singapore-Malaya, the organisation’s secrecy and the sudden outbreak of war on 8 December, 1941, created a dire situation. Consequently, the SOE opted to cooperate with the MCP, recruiting 165 MCP members for the Oriental Mission. These recruits underwent training in the 101 STS with plans for conducting sabotage activities in enemy territory.

However, due to the rapid progress of the war beyond expectations, Singapore-Malaya fell into Japanese hands in less than a hundred days, rendering the collaboration between SOE and MCP ineffective. After the conclusion of the Oriental Mission, SOE members such as Davis and Goodfellow, who retreated to India, participated in the Indian Mission. Through contacts with Lim Bo Seng, they established cooperation with the KMT, recruiting and training KMT agents to infiltrate Malaya via submarines for intelligence gathering operations.

Despite extensive efforts, KMT agents successfully established an intelligence network in Malaya in the late 1943. However, due to the complex situation behind enemy lines, the intelligence network formed by KMT Agents was quickly dismantled by the Japanese Kempeitai, and maritime supply lines were disrupted.

Additionally, damage to radio stations during the same period resulted in KMT agents who infiltrated into Malaya losing contact with the Indian Force 136 headquarters for a year, until early Malaya

1945 when communication was reestablished. Subsequently, a large number of KMT agents were airdropped into Malaya to serve as liaison officers and interpreters for the Allied Forces. Overall, the collaboration between KMT agents and the British SOE involved immense hardships and efforts, particularly noteworthy were the contributions made by Chinese individuals such as Lim Bo Seng, who returned from Southeast Asia to join the cause, greatly contributing to the eventual victory in the war.

Note:

1] John Davis was born in Sutton in 1911. At the end of 1930, he embarked on a journey that led him to connect with Malaya. He was selected as a probationer in a group of ten young men to serve in the Federated Malay States and the Straits Settlements Police. Following six months of training in Kuala Lumpur and temporary assignments in Selangor, John’s career began in earnest in February 1932. In December 1940, upon receiving notice of his transfer from the Federated Malay States Police Service, he was reassigned to the Straits Settlements Police. In July 1941, he was scheduled for transfer to the Special Branch. In May 1941, John Davis embarked on his journey with the Oriental Mission (Shennan, 2007).

2] Since the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, the KMT’s intelligence operations in Singapore-Malaya have been nearly completely dismantled. Agents were arrested by the Japanese, radio stations destroyed, rendering intelligence work impossible (Tan, 2005)

3] The Chinese Seamen’s Wartime Service Corp was an ad-hoc organisation established in Kolkata, India by China and British after the outbreak of the Pacific War. Prior to the war, four British shipping companies – Blue Funnel, Anglo-Saxon, Silver, and Ben Line – employed a large number of Chinese sailors. With the outbreak of the Pacific War, approximately 4,000 Chinese sailors working for British shipping companies found themselves stranded in Kolkata, India. In April 1942, to manage these stranded Chinese sailors, a joint effort between China and Britain led to the formation of the Chinese Seamen’s Wartime Service Corp. The British provided facilities funding, while China dispatched officials to India to organize and train the Chinese sailors (Tang,, 2014b).

4] Goodfellow sought cooperation with Lim Bo Seng because the two were old acquaintances. In December 1941, as Japan approached the southern part of Malaya, Singapore faced imminent danger. The Governor of the Straits Settlements requested the establishment of the Singapore Overseas Chinese Anti-Enemy Mobilization Association by prominent overseas Chinese leaders. On 31 December 31, Lim Bo Seng began serving as the Director of the Labor Service Department of the Anti-Enemy Mobilization Association, responsible for recruiting civilians to engage in defence construction work. On 13 February 13, 1942, while en route from Singapore to India before the retreat, Lim Bo Seng traveled together with Goodfellow (Lianhe Zaobao, 28 June 1994).

5] Chan Chak [陈策] is also known as the “One-Legged General.” When the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, Chan Chak served as the commander of the Guangdong Humen Fortress. In 1938, during the war against the Japanese, Chan Chak sustained an injury to his left foot and subsequently travelled to Hong Kong for medical treatment, where he underwent an amputation surgery. During his recuperation in Hong Kong, Chan Chak was appointed as the full representative of the KMT Government in Hong Kong. In 1942, Chan was awarded a medal by the British for assisting British personnel in evacuating from Hong Kong.

6] Oonishi Detachment’s biggest hit to the MCP was the “9-1” incident that occurred on 1 September 1, 1942. On September 1, 1942, senior MCP leaders held a meeting of senior cadres in the “Batu Caves” (黑风洞) area (attendees included the highest leader of the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army, senior members of the MCP State Committees, or state secretaries), which was betrayed by the then MCP Secretary-General Lai Teck, resulting in the MCP senior cadres attending the meeting being surrounded by the Onishi Detachment, leading to intense gunfights, and ultimately resulting in heavy losses for the MCP (Chin,, 2004, 73). 7 Ishibe Toshiro (石部藤四郎) was the trusted assistant of Onishi Satoru, the head of the Japanese military police in the Singapore-Malaya. After the Japanese attacked Singapore on 15 February, 1941, Ishibe Toshiro participated in the execution of the Sook Ching which resulted in the wrongful deaths of countless Chinese civilians.

7] Ishibe Toshiro (石部藤四郎) was the trusted assistant of Onishi Satoru, the head of the Japanese military police in the Singapore-Malaya. After the Japanese attacked Singapore on 15 February, 1941, Ishibe Toshiro participated in the execution of the Sook Ching which resulted in the wrongful deaths of countless Chinese civilians.

Autore: Shuaishuai Guo, Kee-Chye Ho and Tek-Soon Ling

Lascia un commento