Official War Department doctrine called for tanks to be used as dose support weapons for the infantry, thus the wartime practices for the employment of tanks would continue. A board of officers convened by the War Department in 1919 to study tank tactics recognized the value of tanks as an adjunct to the infantry but declared them incapable of in-dependent action. To emphasize further the association of tanks and infantry the board maintained that the “Tank Service should be under the general supervision of the Chief of infantry and should not constitute an independent service.” Their recommendation that tanks be under Infantry control broke with the wartime arrangement by which the Tank Corps retained autonomy from branch authority. Peacetime exigencies gradually pushed the War Department into placing tanks under the control of the Chief of infantry.

Ultimately the question of a separate Tank Corps can be held before Congressional committees holding hearings on the reorganization of the Army. The question raised in these committees was not over the value of tanks but over the necessity for a separate service. General Peyton C. March, the Chief of Staff, said that American military authorities were fully convinced of the offensive value of tanks. March himself believed the Tank Corps was “technical enough and important enough to keep it as a separate arm.” Disagreeing with March, General Per-shing expressed the belief that tanks should be under the control of the Chief of Infantry; they were an adjunct to that arm. For Congress the question of a separate tank service became one of economic.

Could the government afford an independent tank organization in view of the reduced postwar military budgets? Congressman Harry E. Hull of Iowa presented the problem as follows: “I can see how perhaps in the case of war there some need of a separate organization for tanks might be, but I am unable absolutely to set any reason during peacetime for the creation of the overhead that would have to be established to give you a separate organization.” Evidently the majority of Congress agreed with Mr. Hull. Section 17 of the National Defense Act, as amended by Congress on June 4, 1920, assigned all tank units to the Infantry.

In tactics as well as organization, the reorganization of 1920 had a tremendous impact on tank development. Under Infantry control, tanks naturally had to conform to infantry tactics which meant continuing the dose support mission of World War I. Independent tank attacks had no place in infantry doctrine. A conference was held by the General Service Schools at Fort Leavenworth. Kansas in October and November 1921 discussed the organization and tactics of infantry tanks. The conference report together with comments elicited from other officers and included in the report indicate post-1920 thought on the use of tanks.

To secure dose cooperation between tanks and infantry the report proposed assigning light tank companies as organic components of infantry divisions. Additional tank units would compose a GHQ reserve. This would ensure the maximum use of a limited number of tanks. GHQ thanks. distributed in depth, would be allotted to the corps delivering the main assault. Terrain and the mission of the assault divisions dictated the distribution of available tanks. Departing from established doctrine, the conference suggested the allotment of additional machineguns to each tank company. In a defensive situation these units could serve as machinegun companies. Again, departing from normal doctrine, the conference maintained that in certain situations tanks might successfully assist horse cavalry in performing its missions.

Criticism of this report carne from severals War Department sources. On 9 December 1921 the Tank Board met at Fort Meade to consider the report of the General Service Schools conference. This board criticized the proposal for using tank companies as machinegun units. Tankers required additional training, equipment, and manpower in order to carry out any dual missions. The board maintained that tanks were offensive weapons.

According to the Infantry Board the number of tanks available during wartime would not be sufficient to maintain division tank companies as well as GHQ tank units. Furthermore, divisions might not operate in terrain suitable for the employment of tanks. Tank companies organic to infantry divisions might prove more of a burden than an asset. Writing to the Commandant of the General Service Schools, the Adjutant General charged that instructors at the conference failed to deal with existing organization, units and arms. Instead, they made unauthorized assumptions regarding the tank ser-vice. The Adjutant General caid that uniformity of tactical doctrine cannot exist unless all schools based their teachings on existing organization. Tactically, tanks served as an auxiliary of the infantry. According to the Adjutant General, any discussion of tank tactics had to begin with that premise.

Even before the reorganization the Army took steps to ensure closer cooperation between tanks and infantry. Early in 1920 the Secretary of War, in response to a request by the 1st Division commander, General Summerall, assigned one tank company to each infantry division and assigned one battalion of tanks to the Infantry School at Fort Benning. Alter the reorganization the units retained at Camp Meade included the 16th Tank Battalion (Light), the 17th Tank Battalion (Heavy), and a maintenance company. Meade was also the location of the Tank School and the hub of postwar tank activities. In the event of war Meade would have become a mobilization, training, and replacement center for tank units. Four light tank companies and six separate light tank platoons were the remaining tank units assigned to Regular Army posts. In addition. the National Guard had fifteen light tank companies located throughout the United States. All tank organizations, National Guard and Regular Army, were organic to infantry divisions.

Lack of funds restricted but did not halt the postwar activities of American tank units. For fiscal year 1921 Congress appropriated only $79,000 for use by tank units. During the war, tank crews operated their machines for the entire day, but peacetime budgets dictated that tanks be drawn for a few hours at most because of a lack of funds to buy gasoline. Despite the inconvenience caused by tight budgets, tank units conducted important training and attempted to stimulate interest in tanks. A letter from First Lieutenant Eugene F. Smith, platoon leader of the 1st Platoon, 9th Tank Company at Fort Devens

Massachusetts, to now Colonel Rockenbach aptly reflected the difficulties and nature of tank training during the twenties.

Smith’s platoon moved from winter quarters to Fort Devens between 12 and 17 May 1924. Upon arriving at their training area, they constructed a tank park to house and protect their vehicles. Beginning on 9 June and continuing for three weeks the tanks helped in felling trees and clearing land for a drill field. This was a valuable experience because it gave all hands an opportunity to drive the tanks under difficult conditions. Alter completing the preparation of their training area, the platoon held a test mobilization on 3 July. Despite only 24 hours’ notice the test went well. From 7 to 9 July two tanks of the platoon assisted the 5th Infantry in conducting demonstrations for an Elks convention in Boston. During the second and third weeks of July the platoon assisted in the summer training of the 26th Tank Company of the Massachusetts National Guard. Several reserve tank officers trained with the platoon from 21 July until 2 August.

Tactical exercises with infantry regiments constituted the unit’s primary activity in the latter part of July. On 15 and 16 July the unit participated in field problems with the 13th and 5th Infantry Regiments; these were part of the regiments’ annual tactical inspections. During both of the exercises the tanks moved about eight miles under their own power and impressed the infantry officers present with their ability to keep up with the march column.

On 24, 28, and 31 July, Smith’s platoon participated in the tactical inspection of the 18th Infantry Brigade which was observed by the I Corps commander and some War Department officials. To advertise the mobility and strength of tanks the platoon conducted a demonstration for the visiting dignitaries. One tank crossed a trench system, drove across a bridge, knocked down a tree, and then returned to thc starting point. Smith noted, “We received some very good publicity in the Boston papers because of it.” The platoon held a demonstration of tank-infantry coordination in an attack for ROTC and Organized Reserve Corps personnel on I August. Following this exercise several officers expressed their surprise that tanks could move so rapidly and assist the attacking infantry so well. More than just training his own men, Smith attempted to publicize the tank and impress other officers with its possibilities. The performance of the tanks in these summer maneuvers convinced many officers that they could rely upon tanks in any combat situation. Smith concluded his letter to Rockenbach. “They don’t have to know that on one problem we had to stop and put a new fan belt on one tank, a new water pipe from the pump to the radiator on another and stop every half mile and fill the radiator on another because it sprang a bad leak.”

The most important tank activity of the twenties was the Tank School at Fort Meade. Among its more important functions the school trained personnel for tank units such as Lieutenant Smith’s platoon. Although the enlisted men received instruction only in their specialties, the officers took a more comprehensive course. Included in the officers’ program was instruction on motors, ignition systems, battery maintenance, vehicle chassis, light tanks, heavy tanks weapons, tank marksmanship, tank combat practice, tank history, tank organization, tank tactics, reconnaissance, intelligence, and chemical warfare. The courses were a balance between theory and practice.

The National Guard and Reserve officers course began in March of each year and continued for three months. The Regular officers course was of ten months’ duration. Specialty schools for enlisted men lasted for about three months. After graduation the officers served a tour for several years with a tank unit. Most of the enlisted students came from one of the units at Meade and they returned to their former units upon graduation. But the type of training received by the men created some problems. The skills developed at the school were valuable in a society becoming rapidly motorized and many Tank School graduates left the service to take higher paying civilian jobs. In order to retain trained personnel, the Army began to assign students to the school who had at least two years remaining on their enlistments.

Another activity located at Meade and closely associated with the school was the Tank Board. Originally organized in 1919 as the Tank Corps Technical Board, this body conducted tests, undertook studies, and made recommendations about tanks, tank equipment, tank unit transportation, and similar technical matters. Following the reorganization in 1920 the board disbanded until 1924. In October of that year the Commandant of the Tank School, with the approval of the Chief of Infantry, appointed four permanent members of the Tank Board. This board cooperated with the Tank School, tin Ordnance Department, and other agencies concerned with improving tank development. Army Regulations 75-60 of 30 April 1926 reorganized the board. Rather than four permanently assigned officers, the board now consisted of the Commandant of the Tank School. three officers designated by the Chief of Infantry, and one officer representing the Chief ot Ordnance. In 1929 the Chief of Infantry, upon recommendation of the president of the board, named a recorder and two other members. Similar to the Infantry Board, the Tank Board became a pan of the Office of the Chief of Infantry.

For initial equipment requirements the Tank Board prepared performance specifications. Upon request of the Chief of Infantry, the proper supply facility procured the item and sent it to the board for tests. The board exercised a coordinating role between the tank troops and the supply agencies. Following the conclusion of tests, the board issued a report on the acceptability of the particular piece of equipment. Among the items considered by the Tank Board were communications systems, maintenance equipment, accompanying guns for tanks, a trench digging tank, tank machineguns, and development of new tank models. Members of the board and the test officers worked on projects individually. At frequent meetings the board as a whork reviewed and reported on the individual projects.

The postwar years were both a time of transition and a period of stagnation for American tank development. Although the 1920 reorganization changed the organizational structure of the Tank Corps, small postwar military budgets limited activities. Among other things, this hindered production of new, improved tanks. But a number of officers retained an interest in tanks. They wrote for military periodicals, tried to impress their fellow officers with the capabilities of tanks, and like Lieutenant Smith, attempted to “advertise” tanks. By the end of the decade the Army was contemplating more positive steps for improving the American tank service.

The Experimental Mechanized Forces

By the latter part of the twenties, as the mechanical capability of the tank increased, military officials became more far-sighted about its use. increased mobility and heavier firepower enabled tanks to assume a more independent role.

The Chief of Infantry, and thus the officer having operational control over American tanks, Major General Robert H. Allen wrote in 1927, “My studies at the General Service Schools at Fort Leavenworth have convinced me that the tank was the only new ground weapon born during the World War that would, in future wars, play a noise as conspicuous as the airplane, being the only weapon that could be relied on to overcome the machinegun and prevent a recurrence of the stabilized condition of ‘trench warfare’ similar to the Western Front.”

Even the cavalry saw possibilities for tanks. In 1927 Major General Herbert O. Crosby, the Chief of Cavalry, recommended incorporating tank units into cavalry divisions and assigning antitank weapons to cavalry regiments. Colone) Samuel Rockenbach, commander of the infantry tank service, proposed that the cavalry and other branches, as well as the infantry, contribute to tank development. He said, “I submit that the recent developments by the British will have an effect in modifying our ideas in regard to tanks and that the role of tanks is no longer a special weapon for infantry, but that it is just as important to cavalry divisions, corps, and the Army.” The British efforts, not the proddings by the Americans, precipitated an important change in American tank development.

In early 1927 Secretary of War Dwight Davis witnessed the maneuvers of the British Experimental Mechanized Force at Salisbury Plain. This force, composed largely of tanks and other cross country mechanized vehicles, impressed him so much that later in the year he ordered the organization of a similar American unit to serve as a military laboratory. Including troops from all branches, infantry, cavalry, tanks, artillery, air, ordnance, and supply, the force would be self-sufficient. Davis authorized the commanding officer to ignore existing regulations concerning organization, armament, and equipment. By conducting tests, the War Department sought to develop proper equipment and correct doctrine for the mechanization of additional units. General Charles P. Summerall, then Chief of Staff, ordered the Operations and Training Section (G3) of the General Staff to undertake a study of mechanization which would serve as the basis for the organization of a temporary Experimental Mechanized Force. On 30 December 1927 Summerall approved a preliminary G3 report for the organization of that force. Elements of the Mechanized Force would organize and train at their permanent stations and then assemble at Fort Meade during the summer of 1928.

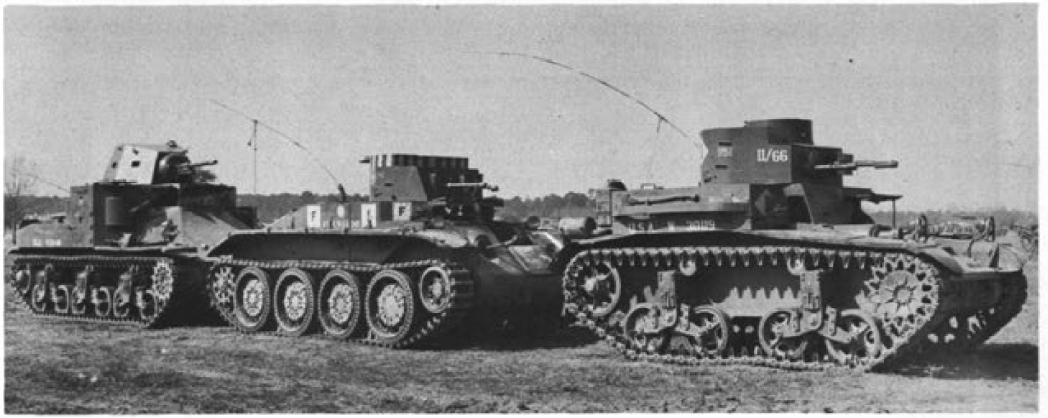

An infantry tank officer and former Commandant of the Tank School, Colonel Oliver Eskridge, commanded the Fort Meade force. Units assigned to the Experimental Mechanized Force included the 16th and 17th Tank Battalions, one separate tank platoon, one battalion of the 34th Infantry, an armored car troop, one battalion of the 6th Field Artillery, an engineer company, a signal company, a medical detachment, the lst Ammunition Train, a chemical warfare platoon, an ordnance maintenance platoon, and a provisional motor repair section. By 3 July 1928 the entire force had assembled.

Major Douglas T. Green, Plans and Training officer for the unit, outlined the program of instruction, training, and tactical exercises. From 9 to 14 July training would consist of instruction on equipment, inspection by the commanding officer, and instruction in short route marches to determine proper methods and procedures for road travel. Following this pre-liminary training, the entire organization would make a five-day march to Aberdeen Proving Ground and Carlisle Barracks and then return to Meade. Such an exercise would give valuable experience in determining proper grouping in march columns, economical rates of march, means of command, supply, and reconnaissance while on the march, and methods of conducting night marches. During the latter part of July and into August the unit would conduct tactical training for offensive operations. From 27 August until 15 September the schedule called for the solution of field problems to test the tactics taught during the preceding training period.

Although the unit generally followed the training program, difficulties arose. Obsolete wartime equipment, which often broke down, proved the greatest handicap. Insufficient equipment and improper balance made the force a poor demonstration unit. Colonel Eskridge requested that the War Department cancel a proposed visit by foreign military attachés because he feared that a poor performance by his troops might embarrass the entire Army. Despite its imperfections, the Experimental Mechanized Force could not be considered a failure. Botti Eskridge and the Assistant Chief of Staff G3, Brigadier General Frank Parker, agreed that the unit provided useful technical and tactical information. By the end of September 1928, the force had accomplished its mission. Therefore, on 19 September, Parker recommended to the Chief of Staff that the unit be disbanded as originally planned. General Summerall approved this on the twentieth. After 1 October all the component units of the Experimental Mechanized Force returned to their home stations.

In the spring of 1928, while plan progressed for the organization of the experimental unit, the War Department began planning for a long-range mechanization program. General Parker submitted a report in March 1928 which emphasized the necessity of firepower and mobility to achieve success in modem warfare. Parker regarded tanks as a means of restoring the power of decision to baule. During World War I and after, tanks were tied to the infantry thus reducing their mobility and shock effect. Instead of this, Parker believed that they should drive forward and attack hostile reserves and rear installations. Not adopting an extreme pro-mechanization position, he considered entirely mechanized armies inconceivable. They were prohibitively expensive; logistical support would be difficult; machines could not operate in all kinds of terrain and weather. But mechanized units were valuable additions to any offensive operation.

The potential user of mechanized units outlined in Parker’s report included operating as the spearhead of an important attack, as a counterattack force, and as the advance or flank guard of strategic formations. Proper organization was necessary for any mechanized force. mese required sufficient striking power to penetrate the enemy’s defense and disorganize his reserves. But mechanized units could not be so large as to become unwieldy. Tank companies comprised the principal striking power of any mechanized force. As envisaged in Parker’s report, light tanks, the leading element in an assault, attacked weak points in the defense; enemy flanks were particularly vulnerable. Self-propelled artillery and medium tanks supported the advance by overcoming strong points and widening gaps in the enemy’s fine. Infantry, brought forward in mechanized vehicles, consolidated the ground captured by the tanks. Supply, maintenance, and other support elements were mechanized in order to keep up with the advance.

In concluding his report, Parker made several specific recommendations for the long-range development of mechanization in the United States Army. He proposed that procurement of equipment for mechanized units, including light and medium tanks, a reconnaissance car, cross-country vehicles for infantry and support units, and self-propelled artillery, commence during the 1930 fiscal year. Congress had to pass the necessary legislation to establish one permanent mechanized unit during fiscal 1931. This unit would use both modem and obsolete equipment. During 1931 and 1932 the obsolete equipment would be progressively phased out. Secretary of War Davis approved Parker’s report as the basis for future development and organized a board of General Staff officer to prepare the details for future action.

Among those appointed to this board was Major Adna R. Chaffee, Jr., a cavalryman and a member of the G3 section of the War Department General Staff. From the time of his assignment to G3 in lune 1927 until his death in the summer of 1941, Chaffee remained one of the leading American advocates of mechanization. Before 1927 Chaffee knew nothing about tanks. Realizing that G3 was beginning studies on mechanization, Chaffee learned all he could about the subject. At Rochester he witnessed the demonstration of a new tank, capable of 18 miles per hour, built by James Cunningham and Sons. Chaffee also saw a test of the Christie tank which could go 42 miles per hour.

These demonstrations convinced him that tanks should not be tied to the infantry, advancing at a walking pace. The maneuvers of the British mechanized units also aroused his interest. At this time a friend of Chaffee’s, Charles G. Mettler, was serving as military attaché to Great Britain. When Mettler visited Washington in 1927 Chaffee questioned him about British efforts in mechanization. Some years later Mettler recalled, “He loaded me with a terrible list of things he wanted to know and expected me to find out for him when I returned to London.” His own observations and information received from sources such as Mettler stimulated Chaffee to promote mechanization. Although not immediately the moving force in American mechanization (he ranked sixth in seniority on the Mechanization Board appointed in 1928) Chaffee’s influence gradually increased and his interest never waned. But the development of mechanization cannot be attributed to any one person. Progress was slow and the result of the efforts of many officers.

Initially the eleven man Mechanization Board met on 15 May 1928 in Room 346 of the State, War, and Navy Building. Thereafter, it met from time to time as work demanded. Members of the board, who were from all branches of service, witnessed demonstrations of new tank models and the exercises of the Experimental Mechanized Force. In their final re-port, issued in October 1928, the board reached conclusions about mechanization similar to General Parker’s report. The group also outlined a tentative program for future development. The board recommended the organization of a unit similar to the recently disbanded Experimental Mechanized Force to serve as a technical and tactical laboratory. A force of 131 officers and 1896 men would be organized into a headquarters, one light tank battalion, two mechanized infantry battalions, one field artillery battalion, an engineer company, and a medical detachment.

In order that tactical doctrine would keep pace with mechanical development, the board proposed supplying the force with the latest equipment. Although not recommending formation of a separate branch, the board emphasized the necessity of forgetting branch rivalries and traditions in order to make progress in the field of mechanization. With one exception, all of the branch chiefs concurred in the report. On 31 October 1931 the Secretary of War approved the recommendations but because of budgetary considerations postponed organizing a mechanized force from fiscal 1930 until fiscal 1931.

Major General Stephen O. Fuqua, the Chief of Infantry, was the exception among the branch chiefs concurring in the report. Earlier he had disagreed with the conclusions of General Parker’s report on mechanization. Fuqua’s criticism was based strictly on branch rivalry; exactly the son of thing the Mechanization Board wanted to avoid. A separate mechanized force threatened the complete control over tanks which the infantry had had sine 1920. Fuqua protested to Parker, “The tendency in this study to set up another branch of the service with the tank as its nucleus is heavily opposed. It is as unsound as was the attempt by the Air Corps to separate itself from the rest of the Army. The tank is a weapon and as such it is an auxiliary to the infantryman, as is every other arm or weapon that exists.” According to Fuqua, the authority for tank development should remain where it was—with the Chief of Infantry. De-spite the General’s protests, the War Department proceeded with its plans for mechanization.

In his 1930 annual report, the Chief of Staff, General Summerall, reaffirmed the Army’s commitment to proceed with the formation of a mechanized force. He declared, “From being an immediate auxiliary of the infantry the tank will become a weapon exercising offensive power in its own right.” Recognizing the importance of a suitable tank force, Summerall ordered that the proposed Mechanized Force become a permanent unit, not a temporary or experimental organization. But the development program, so carefully planned, ran into unexpected difficulties.

The inability of the Ordnance Department to produce a tank acceptable to the Tank Board and the lack of funds delayed the organization of the mechanized force. Failure to produce a suitable tank was particularly crucial because tanks formed the nucleus of the force. Everything else might disappear and the tanks could still accomplish at least pan of the mission; but without tanks the remainder of the force was useless. Until the late twenties the Army used surplus wartime equipment. As the experience of the Experimental Mechanized Force indicated, this equipment was obsolete. Unfortunately, the advent of the Great Depression paralleled the decline of wartime materiel. Retrenchment and stabilization of military budgets made modernization and reequipment program difficult. The War Department had to determine how best to maintain the Army with limited funds. And availability of funds often affected policy. Ordnance Department estimates for fiscal year 1932 reflected this trend. Priorities for the submitted Ordnance budget of $2.4 million were for limited service test and procurement of semi-automatic rifles, 3-inch antiaircraft guns, and as many tanks as possible with the remaining money.

When the final War Department budget directive reduced the amount to $1 million, the General Staff, which determined priorities, decided to use the money for the highest priority items: the rifles and only a few tanks. The Staff decided that progress in tank development warranted the purchase of only a few tanks to test tactics and keep up with the latest technology. Because of these decisions, the Mechanized Force, when finally organized at Fort Eustis in November 1930, used unsuitable, obsolete equipment. On 24 November 1930 Colonel Edward O. Croft, the Acting Assistant Chief of Staff, G3, selected units for the force.

Company A of the 1st Tank Regiment, equipped with six World War Renaults, five modernized Renaults, and four TIE 1 tanks, formed the nucleus of the unit. One armored car troop of ten vehicles served as the reconnaissance element. One battery of the 6th Field Artillery, equipped with obsolete service trucks, not self-propelled guns as the War Department studies advocated, provided fire support. Equipment problems also plagued the engineer company assigned to the force as its transportation initially consisted of horse-drawn wagons. Fifteen light tanks, 10 armored cars, seven tractors, 66 trucks, 22 automobiles and less than 600 men composed the Mechanized Force.

General Summerall selected Colonel Daniel Van Voorhis as commander of the unit. Van Voorhis, a career cavalry officer and recent (1929) graduate of the Army War College, had no previous experience with tanks. As executive officer, Summerall picked Major Sereno E. Brett, a former wartime commander of the 304th Tank Brigade. During September 1930 Van Voorhis, Brett, and Chaffee, now head of the G3 Troop Training Section, visited Aberdeen Proving Ground, Holabird Quartermaster Depot, and Fort Eustis. They conferred with officers at these posts relative to the equipment and organization of the Mechanized Force. The Chief of Staff based the tactical and training missions of the force on the findings of these officers. In combat the Mechanized Force would execute missions presenting an opportunity for tactical and strategical mobility and quick, hard striking power. The training mission of the unit was to determine the proper tactics involved in the operation of fast tanks with other mechanized and motorized arms.

From 1 November until 31 December the force would organize and conduct individual training. Unit training and combined drills to perfect teamwork followed. Beginning in March and continuing until the end of the fiscal year in lune, the unit planned to hold field exercises and maneuvers with troops of other arms. During the period from 1 November 1930 until 31 lune 1931 the Mechanized Force carried out its proposed training schedule. The 34th Infantry (Motorized) and the Air Corps Tactical School assisted in some of the maneuvers. Operations consisted of command post exercises, field problems, maneuvers, demonstrations, and ceremonies. Among the exercises were night tactical and strategic marches, offensive combat against entrenched infantry, offensive operations against another mechanized force, attacks involving wide turning movements, seizure of key positions, and operations as a covering force for a larger unit.

All of the missions executed by the Mechanized Force emphasized its mobility. Traditionally, cavalry was the branch of mobile warfare. But during the twenties the cavalry had done little in the field of mechanization. Recognizing these facts, General Douglas MacArthur, who became Chief of Staff on 21 November 1930, ordered the Mechanized Force disbanded and directed all branches, in particular the cavalry, to mechanize so far as possible. This decision affected the development of American mechanization down to the organization of the Armored Force in 1940.

Refernces:

The author used several sources. Foremost were records in the National Archives. Departmental memos, reports from the various conferences considering tanks, and some personal correspondence were found in Record Group 94 (The Adjutant General’s File) and Record Group 177 (The Chiefs of Arms File). Other primary sources included Congressional documents such as the Hearings Before the House Military Affairs Committee, Vol. I (1919) and the Reorganization of the Army Hearings, Vol. I (1919); both of these volumes were published from the records of the 66th Congress, 1st Session. War Department Annual Reports also provided valuable facts and figures about tank units.

Three Infantry Journal articles furnished information on tank activities during the twenties: William E. Speidel, “The Tank School,” June 1925; “The Tank Board,” August 1926; Ralph E. Jones, “The Tank School and Tank Board.” The Farago biography of Patton and Eisenhower’s At Ease! (1967) gave useful insights into the activities of these officers. Material at the National Archives also constituted the primary source for Chapter III. Memos by branch chiefs, the Assistant Chiefs of Staff, and the AG were found in the Adjutant General’s File, Record Group 94. Operations reports of the mechanized units and the report of the Mechanization Board were also in this file. Additional material was found in RG 177, the Chiefs of Arms File. General Chaffee’s obituary in the April 1942 West Point Assembly, written by Charles G. Mettler, provided some useful information. “The Impact of the Great Depression on the Army, 1929-36,” an unpublished dissertation from Indiana University by John W. Killigrew, was also very good. War Department Annual Reports contained data on tank development and outlined overall policy..

Autore: Timothy K. Nenninger

Fonte: ARMOR Jul-Dec 1969

Lascia un commento