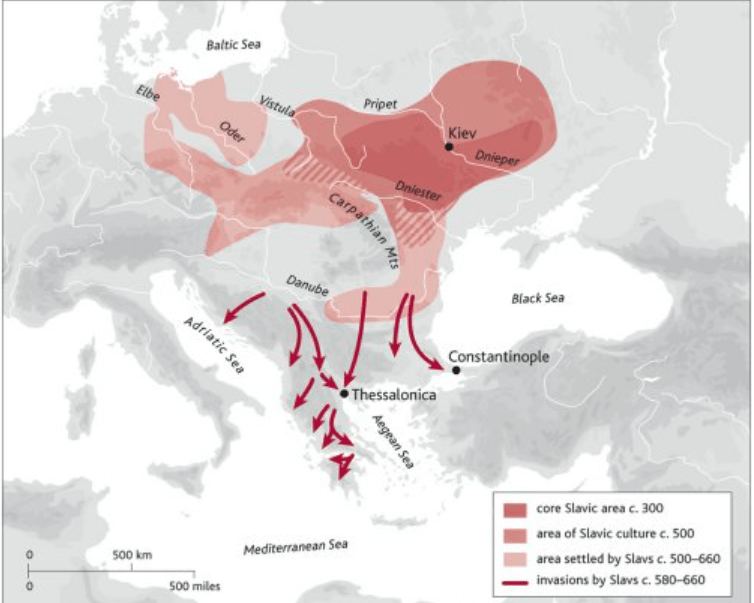

Beginning in the 1st century AD, Slavic tribes participated in the struggle against the Roman Empire. Ancient sources mention East Slavic tribes that fought against the Roman conquerors. More detailed information about the wars of the Slavic tribes dates back to the 6th–8th centuries, when the Slavs fought against the Eastern Roman Empire, in which feudal relations were developing at that time, which determined its transformation into the Byzantine Empire.

By the beginning of the 6th century, the onslaught of the Slavic tribes from across the Danube had become so intense that the Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius was forced in 512 to build a line of fortifications stretching 85 km from Selimvria on the Sea of Marmara to Derkos on Pontus (the Black Sea). This line of fortifications was called the “Long Wall”. One of its contemporaries called it “a banner of impotence, a monument to cowardice”. The “Long Wall” was located 60 km from the capital.

In the second quarter of the 6th century, Justinian, preparing for the fight against the Slavs, strengthened his army and built defensive structures. On the Danube, old fortresses were restored and new large ones were built; to the north of the Balkan ridge, a second defensive line was built, consisting of 75 fortifications; to the south of the ridge, a third defensive line was created (100 fortifications); in the central part of the Balkan Peninsula, Procopius counted 244, and in its western strip 143 fortifications. All these defensive works placed a heavy burden on the population, which caused great discontent and negatively affected the political and moral state of the garrisons of the fortifications.

The first information about the Slavic campaigns across the Danube dates back to the last decade of the 5th century. In 499, the Slavs invaded Thrace. They were opposed by the Master of the Eastern Roman army with a 15,000-strong army and a convoy of 520 wagons. The battle took place on the river Cutra. The Master’s army was defeated. The details of this battle have not reached us, it is only known that the Master lost four thousand people killed and drowned.

In 517, large forces of Slavs with significant cavalry invaded the Eastern Roman Empire, passed through Macedonia and Thessaly and reached Thermopylae; in the west, they penetrated into Old Epirus. Almost the entire Balkan Peninsula fell into the hands of the Slavs.

When Justinian came to power, he appointed, according to Procopius, Chilbudius as the head of the Ister River guard, who successfully defended the Danube line from attacks by Slavic tribes for three years in a row. Chilbudius crossed the Danube every year, penetrated deep into the territory occupied by the Slavs, and carried out devastation there. In 534, Chilbudius crossed the river with a small detachment. The Slavs “all opposed him. The battle was fierce; many Romans fell, including their leader Chilbudius.” After this victory, the Slavs freely crossed the Danube to invade deep into the Balkan Peninsula.

Thus, the fortifications themselves did not block the Slavs’ path to the Balkans; reliable protection was provided by the border troops, led by an experienced military leader, who actively defended the Danube line. Successes in the fight against the Slavs contributed to the fact that Hilbudius overestimated his forces and underestimated the enemy’s forces. Therefore, he crossed to the left bank of the river at the head of a small detachment, which the Slavs easily destroyed.

In 547, the Slavic army again crossed the Ister River and captured all of Illyria as far as Epidamnus. “Even many of the fortifications that had been there in the past seemed strong, since no one defended them, the Slavs managed to take…”. The commander of Illyria with a 15,000-strong army followed the Slavs. Before his eyes, the Slavs captured the fortifications, but he did not dare to engage in battle, since he did not have sufficient forces.

In 551, a detachment of Slavs numbering over 3,000 people crossed the Istra River without encountering any resistance. Then, after crossing the Gevr (Maritsa) River, the detachment split into two detachments. The Roman commander, who had large forces, decided to take advantage of this advantage and destroy the disparate detachments in open battle. But the Slavs forestalled the Romans and defeated them with a surprise attack from two directions. This fact demonstrates the ability of the Slavic commanders to organize the interaction of their detachments and carry out a sudden simultaneous attack on an enemy with superior forces and acting offensively.

Following this, regular cavalry under the command of Asbad, who served in the bodyguard of Emperor Justinian, was sent against the Slavs. The cavalry unit was stationed in the Thracian fortress of Tzurula and consisted of excellent horsemen. One of the Slavic units attacked the Roman cavalry and put it to flight. Many Roman horsemen were killed, and Asbad himself was captured. From this example, we can conclude that the Slavs had cavalry that successfully fought the Roman regular cavalry.

Having defeated the regular field troops, the Slavic troops began to besiege the fortresses in Thrace and Illyria. Procopius reports quite detailed information about the capture of the strong coastal fortress of Toper by the Slavs, located on the Thracian coast 12 days’ journey from Byzantium. This fortress had a fairly strong garrison and up to 15 thousand combat-ready men – residents of the city.

The Slavs decided first of all to lure the garrison out of the fortress and destroy it. For this purpose, the greater part of their forces laid in ambush and hid in difficult places, and a small detachment approached the eastern gate and began to shoot at the Roman soldiers. “The Roman soldiers who were in the garrison, imagining that there were no more enemies than they saw, took up arms and immediately went out against them all. The barbarians began to retreat, pretending to the attackers that, frightened by them, they had turned to flight; the Romans, carried away by the pursuit, found themselves far ahead of the fortifications. Then those who were in ambush rose up and, finding themselves in the rear of the pursuers, cut off their ability to return back to the city. And those who pretended to retreat, turning their faces to the Romans, put them between two fires. The barbarians destroyed them all and then rushed to the walls.”

Thus the garrison of Topera was destroyed. This episode testifies to the good organization of the interaction of two Slavic detachments, attacking the Romans from the front and from the rear. The Roman commander, having no information about the enemy, decided on a general sortie with the forces of the entire garrison, without providing it with either a reserve or the organization of reconnaissance and security.

The Slavs moved to storm the fortress, which was defended by the city’s population. The first attack, insufficiently well prepared, was repelled. The defenders threw stones at the attackers, poured boiling oil and resin on them. But the success of the townspeople was temporary. Slavic archers began to shoot at the wall and forced the defenders to leave it. Following this, the attackers put ladders to the walls, penetrated the city and captured it.

Procopius showed the techniques of capturing a fortress, in which the interaction of archers and assault troops is characteristic. The Slavs were accurate archers and therefore were able to force the defenders to leave the wall.

The campaign of the three-thousand-strong detachment of Slavs demonstrates their combat capability and skillful tactics both in field combat and in capturing a fortress. The Slavs are characterized by skillful organization of tactical interaction between several detachments. During this entire campaign, the detachment of Slavs inflicted defeats on superior enemy forces.

In 552, a large army of Slavs crossed the Ister and invaded Thrace. Justinian learned from captured prisoners that the Slavs had decided to first besiege and take Thessalonica and the cities around it. Having received this information, the emperor ordered the already prepared campaign in Italy to be postponed and sent a large army under the command of his nephew Herman against the Slavs.

The Slavs learned from the prisoners that Herman was preparing to repel their attack with a large army. Therefore, the campaign against Thessalonica was interrupted, the Slavic army turned back and, having passed through the mountains across Illyria, retreated to Dalmatia. Herman soon died. The Slavs decided to take advantage of this and implement their previously outlined plan. Having strengthened their army with a newly arrived detachment, which successfully crossed the Ister, the Slavs again invaded the borders of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Procopius notes that the Slavic army was divided into three parts and advanced in three directions. Without encountering serious resistance, the Slavs occupied a significant territory, where they settled, “wintering here, as if in their own land, without fear of the enemy.”

To fight the Slavs, Justinian allocated a select army with five of the best commanders, appointing Scholasticus as commander-in-chief. Near Adrianople, which was five days’ journey from Byzantium, Scholasticus met a large detachment of Slavs, who set up camp on a mountain and prepared for battle.

The Romans settled down on the plain, a little further away, and for a long time did not dare to engage in battle. Soon, the army of Scholasticus began to feel a shortage of food, the soldiers began to express discontent. Under pressure from the soldiers, a decision was made to give battle to the Slavs. In this battle, the Roman army suffered defeat.

Then the Slavs moved towards Byzantium and approached the “Long Walls”. The Roman army, having recovered from the defeat at Adrianople, followed the enemy and suddenly attacked the Slavs not far from the “Long Walls”. As a result of the victory at Adrianople, the Slavs’ vigilance weakened, and therefore the Romans’ sudden attack was successful and forced the Slavs to retreat beyond the Istra.

There is every reason to consider the campaign of the Slavic detachment in 551 and the large campaign of large Slavic forces in 552 in connection. In this case, the campaign of the three-thousand-strong detachment and its siege of the city of Toner was, by its nature, a strategic reconnaissance mission, which was a test of the combat capability of Justinian’s field troops and the resistance of his fortresses. Having obtained all the necessary information, the Slavs organized a large campaign in 552, which significantly weakened the Eastern Roman Empire.

Studying the campaign of 552 allows us to establish some features of the military art of the ancient Slavs. First of all, it is worth noting the ability of the Slavic commanders to assess the situation – to determine the balance of forces and take into account the quality of the enemy’s command. This is why the Slavs were able to make the right decision – to avoid battle and retreat to Dalmatia.

Strengthened by the arrival of a new detachment (possibly this detachment was called in) and having received information about the death of Herman, the Slavs, having divided into three detachments, went on the offensive, which significantly complicated the Romans’ defense. Near Adrianople, a large Slavic detachment occupied a strong position, from which the Romans did not dare to attack it. The Slavs’ defensive method of action in this situation contributed to the weakening of the enemy troops.

The Roman army, forced into battle, suffered a defeat. The Slavs began to develop their success in the direction of Byzantium, but, having lost their vigilance, were suddenly attacked and retreated beyond the Istre.

In general, it should be noted that the Slavs skillfully used offensive and defensive methods of warfare and combat.

The invasion of the Slavs into the Eastern Roman Empire did not cease. To fight the Slavs, Emperor Tiberius entered into an alliance with the Avars around 582. At the same time, large campaigns were undertaken against the Slavs. In 584, the Slavs were pushed back beyond the Balkans. But already in 586, Slavic troops appeared again near Adrianople. Emperor Mauritius (582–602) undertook several new campaigns to push the Slavs back beyond the Istra River.

Of interest to the history of military art is the campaign in 589 of Peter, the commander of Mauritius, against a strong Slavic tribe led by Pyragast. Theophylact Simocattes reports interesting details of the Slavs’ defense of river borders.

The Emperor demanded quick and decisive action from Peter. Peter’s army left the fortified camp and reached the area where the Slavs were in four marches. Peter’s detachment had to force the river. A group of 20 soldiers was sent out to reconnoiter the enemy, moving at night and resting during the day. Having made a difficult night march and crossed the river, the group settled in the thickets to rest, and did not post a guard. The soldiers fell asleep and were discovered by a Slavic cavalry detachment. All the Romans were taken prisoner. The captured scouts told about the plan of the Roman command.

Piragast, having learned of the enemy’s plan, moved with large forces to the place where the Romans were crossing the river and there secretly positioned themselves in the forest. The Roman army approached the crossing. Peter, not supposing that there might be an enemy at this place, ordered the river to be crossed in separate detachments. When the first thousand people crossed to the other bank, the Slavs surrounded them and destroyed them. “Having learned of this, the commander ordered the army to cross the river without dividing into small detachments, so that, crossing the river little by little, they would not become an unnecessary and easy victim of the enemy. When, in this way, the Roman army had lined up their ranks, the barbarians in turn lined up on the river bank. And so the Romans began to strike the barbarians from their ships with arrows and spears.” Clouds of arrows and spears forced the Slavs to clear the bank. Taking advantage of this, the Romans landed their large forces. Pyragast was mortally wounded, and the Slavic army retreated in disarray under the onslaught of the Romans. Peter, due to the lack of cavalry, was unable to organize a pursuit.

The next day, the guides who were leading the army got lost. The Romans had no water for three days and quenched their thirst with wine. The army could have perished if not for a prisoner who pointed out that the Helicabia River was nearby. The next morning, the Romans approached the river and rushed to the water. The Slavs, who were in ambush on the opposite high bank, began to defeat the Romans. “And so the Romans, having built ships, crossed the river to engage the enemy in open battle. When the army found itself on the opposite bank, the barbarians immediately attacked the Romans in their entirety and overpowered them. The defeated Romans fled. Since Peter was utterly defeated by the barbarians, Priscus was appointed commander-in-chief, and Peter, relieved of command, returned to Byzantium.”

The Slavs actively defended water borders. If the enemy began to cross in small detachments, the Slavs destroyed them immediately after landing. Simocattes says that the Slavs “lined up on the river bank”, i.e. used a battle formation. This message refutes the assertion of Mauritius that the Slavs “do not recognize military formation, are incapable of fighting in a proper battle”. Only data on the nature of the battle order of the Slavs is missing, but the fact of the formation for battle is repeatedly noted by ancient authors. If the Slavs managed to inflict significant losses on the enemy during his crossing of the river, they prepared and carried out a general counterattack at the moment when the enemy found himself on the opposite bank and did not have time to line up for battle. John of Ephesus correctly notes that the Slavs “learned to wage war better than the Romans”. Reconnaissance, offensive and defensive actions of the Slavic army are characterized by skillful organization and their skillful execution.

The information provided by Bishop John of Thessalonica about the siege of this city by the Slavs in 597 is interesting. John described the siege equipment of the Slavs. The siege engines consisted of stone throwing tools, “turtles”, iron rams and hooks. The stone throwing tools had a quadrangular shape, a wide base and a narrow top, where thick wooden cylinders covered with iron were attached. The throwing machine was covered with thick boards on three sides. This protected the soldiers operating it from enemy arrows. The throwing machines threw large stones. The “turtles” were initially covered with dry skins, but this could not protect them from hot resin, so the dry skins were then replaced with fresh skins from freshly killed bulls and camels.

Having installed the siege engines, the Slavs, under cover of throwing machines and archers, moved the “turtles” close to the fortress wall and began to shake it with iron rams and destroy it with hooks. This is how breaches were made for the assault columns.

The siege of Thessalonica lasted six days. The garrison made several sorties, which, however, did not affect the course of the siege. On the seventh day, the besiegers abandoned their camp and all siege equipment and retreated to the mountains. Thus, the Slavs in the 6th century had siege technology that was perfect for its time and skillfully used it.

During the reign of Emperor Heraclius (610–641), Byzantium continued to wage a difficult struggle with the Slavs. At this time, the military reform known as the “fem system” was completed in the empire, carried out with the aim of strengthening the army.

Themes were initially called detachments of troops, and then the areas of their deployment. Warriors received plots of land and lived off the income from them. Power in the farm was concentrated in the hands of the military leader. In an effort to strengthen the army, the Byzantine emperors objectively contributed to the development of feudal relations by reforming the “fem system”. A characteristic feature of the purely military content of the reform was the borrowing of military art from the Slavs. Even Mauritius recommended introducing Slavic methods of warfare and combat into the Byzantine army. Moreover, the Byzantine emperors sought to strengthen their army with Slavic detachments and invited Slavic leaders to serve them.

Some historians consider wars with the Arabs to be the main reason for the introduction of the feudal system. But wars with the Arabs did not threaten the existence of the empire at that time. At the turn of the 7th century, the main enemy of Byzantium were the Slavs, the struggle with whom caused the need for military reform.

In the 8th century, military and naval laws were developed that determined the organization of the army and navy. Byzantium had a strong navy equipped with advanced technology. The navy was intended to protect Constantinople from the sea, and powerful fortifications provided it with protection from land. During the campaigns of the Byzantine army, the navy interacted with it or carried out landings.

The Byzantine army in the 9th century numbered up to 120 thousand people. It was mainly cavalry. Over the course of 300 years after the reign of Justinian, the Byzantine infantry as a branch of the military finally lost its significance. At the beginning of the 10th century, Emperor Leo VI noted that it was impossible to find people who knew how to use a bow. He believed that it was necessary for one third, or even half, of the infantry to consist of archers with 30 to 40 arrows. But this was an unrealistic desire. The authors of that time do not mention hand-to-hand combat of the infantry at all. The infantry was located in the last line of the battle formation and did not influence the outcome of the battle, although it was often numerous. The infantry was viewed as a burden that hindered the actions of the cavalry.

The cavalry was the main branch of the Byzantine army. The bulk of the cavalry were federates who served for good pay and often went over to the enemy if it was advantageous to them. The Byzantine cavalry made up the first line of the battle formation and fought in compact formations. The usual depth of its formation was no less than five and no more than ten ranks. The battle formation of the cavalry was divided along the front and in depth: part of it acted in loose formation, another, the main part, was in close formation and had to support the first, the third part was intended to envelop the flank of the enemy, the fourth pinned down the other flank of the enemy.

The so-called “Greek fire”, which preceded the advent of gunpowder, was widely used in the army and navy of Byzantium. As early as 673, “Greek fire” was successfully used in the defense of Constantinople; it burned the Arab fleet.

The Byzantine Emperor Leo III (717–740) describes a fire trireme that had a tube on its bow for throwing fire at an enemy ship. He also mentions hand-held tubes with “Greek fire” that were thrown at the enemy, and attempts to use “Greek fire” in the actions of war chariots. Along with the description of explosives, there is a mention of “liquid fire” (probably oil), which was thrown at enemy ships in barrels, tubes, and balls. Leo VI wrote in his “Tactics” (early 10th century):

“Following custom, one should always have a copper-lined pipe on the bow of the ship to throw this fire at the enemy. Of the two oarsmen on the bow, one should be a piper.”

Here is one of the 12th century recipes for producing “Greek fire”: one part rosin, one part sulfur, six parts saltpeter in finely ground form were dissolved in linseed or laurel oil, then placed in a pipe or a wooden trunk and lit. The second recipe for “flying fire” is as follows: one part sulfur, two parts linden or willow charcoal, six parts saltpeter, all crushed in a marble mortar. Until the 12th century, Byzantium retained a monopoly on the use of “Greek fire” in naval combat, and then it became the property of all European nations.

By the beginning of the 7th century, many Slavic tribes had firmly established themselves on the Balkan Peninsula, thus creating a base for more distant campaigns. A number of Slavic sea campaigns were recorded during this period. Thus, in 610, the Slavs besieged Thessaloniki from the sea and from land. In 623, a Slavic flotilla appeared off the coast of Crete and successfully landed its troops there. In 626, when Emperor Heraclius and his army left for Asia Minor to fight the Persians, the Slavs, in alliance with the Avars, attacked the capital of the Byzantine Empire.

In June, the Slavic fleet approached Byzantium and landed troops. The “Long Wall” was bypassed. The capital was blockaded from the sea and from the land. In one week, the allies prepared to storm its fortress walls. A large number of throwing machines were made and 12 large assault towers were built, the height of which reached the height of the walls

Autore: Evgeniy Andreevich Razin (Евгений Андреевич Разин)

Lascia un commento