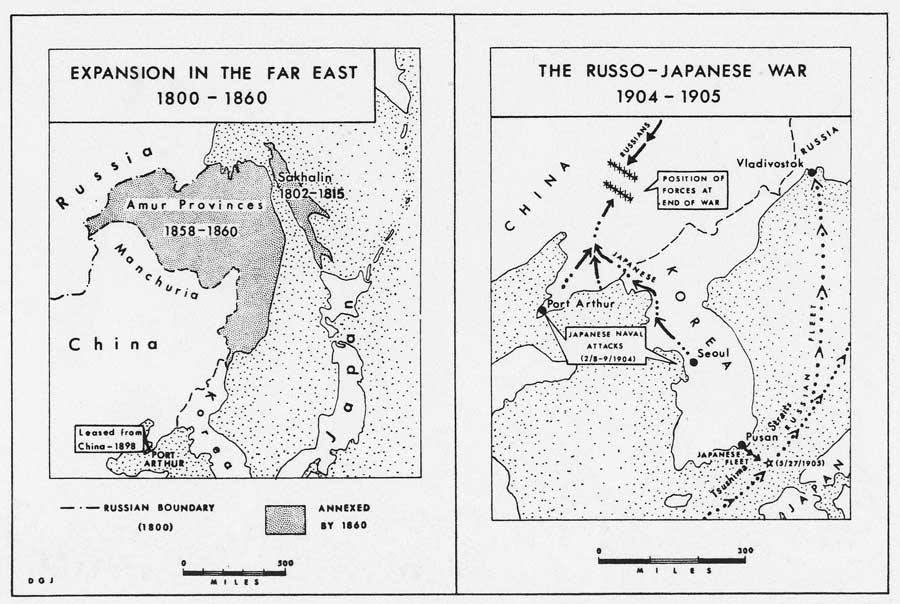

In March 1902, Russia , in order to protect the East China Railway, occupied Manchuria with its troops, pledging to evacuate it within three deadlines; the last was October 8, 1903. This obligation was not fulfilled on the grounds that the state of China did not guarantee the safety of the Russian railway line. In July 1903, a diplomatic exchange of opinions began between Russia and Japan, first concerning Korea alone, then Korea and Manchuria.

The correspondence on this matter has not been published, and its contents are known only in general terms. As far as is known, Russia agreed to recognize Japan’s protectorate over Korea, on condition that it be provided with two strongholds in Korea, Mozampo and Mokpo, necessary for securing the Port Arthur-Vladivostok communication line. Japan did not agree, believing that possession of these ports would create dominance over the Korea Strait, which was unacceptable from the point of view of Japanese interests.

Japan expressed this opinion in a note on December 21, 1903, in which it also demanded:

1) maintenance of the open door policy in Manchuria and the granting of equal rights to trade for all countries there, with Japan expressing its readiness to renounce the privileges it had enjoyed there until then; 2) recognition of the fact that Japan has interests in Korea that are preferential to other powers; 3) the evacuation of Yonampo (a city on the Yalu River), since its occupation hinders the opening of the Yalu River for foreign trade.

Then Japan, “without even waiting to receive the latest response proposals from Our Government,” the Imperial Manifesto on the declaration of war states, “notified the termination of negotiations and the severance of diplomatic relations with Russia.”

This took place on January 24, 1904, and in the note transmitted to Count Lamsdorf it was stated that, seeing no need to prolong the negotiations, which had become useless, Japan was recalling its embassy from St. Petersburg and reserving the right to resort to those “independent actions” that it considered necessary to protect its interests. Russia also recalled its embassy from Tokyo, placing responsibility on Japan for the consequences that might result from such a cessation of diplomatic relations.

In order to clarify the international position of the powers that had started the war, it is necessary to bear in mind the treaty of January 30, 1902 between England and Japan by virtue of which England is obliged to support Japan if it has to wage war with two powers at once. The answer to this treaty was the Franco-Russian declaration of March 3, 1902, which confirmed the identity of the interests of France and Russia in the East; although not directly, it follows from it that in the event of a war between Russia and two powers, France is obliged to support Russia. Thus, China, by its intervention in the war, can turn the clash between Russia and Japan into a world war.

Apparently fearing this, Japan, as early as January 7, 1904, addressed China with a reasoned exhortation to maintain the strictest neutrality in the event of a possible war between Russia and Japan. In order to determine the actual military forces of the belligerent powers at the beginning of the war, it must be borne in mind that the war was to be waged simultaneously at sea and on land. The naval forces of both opponents are easy to calculate.

In the Great Ocean:

| Russia has | Japan has | |||||

| Numbers of vessels | Tonnage | Numbers of guns | Numbers of vessels | Tonnage | Numbers of guns | |

| Squadron battleships of the 1st class. | 7 | 84028 | 526 | 6 | 85496 | 376 |

| the 2nd class | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7335 | 16 |

| Armored cruisers | 4 | 33297 | 228 | 9 | 76230 | 337 |

| Class I cruisers | 5 | 31960 | 186 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Class II | 2 | 6200 | 31 | 10 | 41089 | 302 |

| the III class | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 21640 | 147 |

A certain advantage was thus on the side of Japan, and was even more significant if we take into account the gunboats, counter-destroyers, destroyers and all sorts of auxiliary vessels; but this advantage of Japan could have turned into a significant advantage for Russia if Admiral Virenius’ squadron (the battleship Oslyabya and the cruiser Dmitry Donskoy), which had been on its way there before the start of the war but had received orders to return, or, even more so, the Russian Baltic squadron, had come to the aid of the Grand Ocean Fleet.

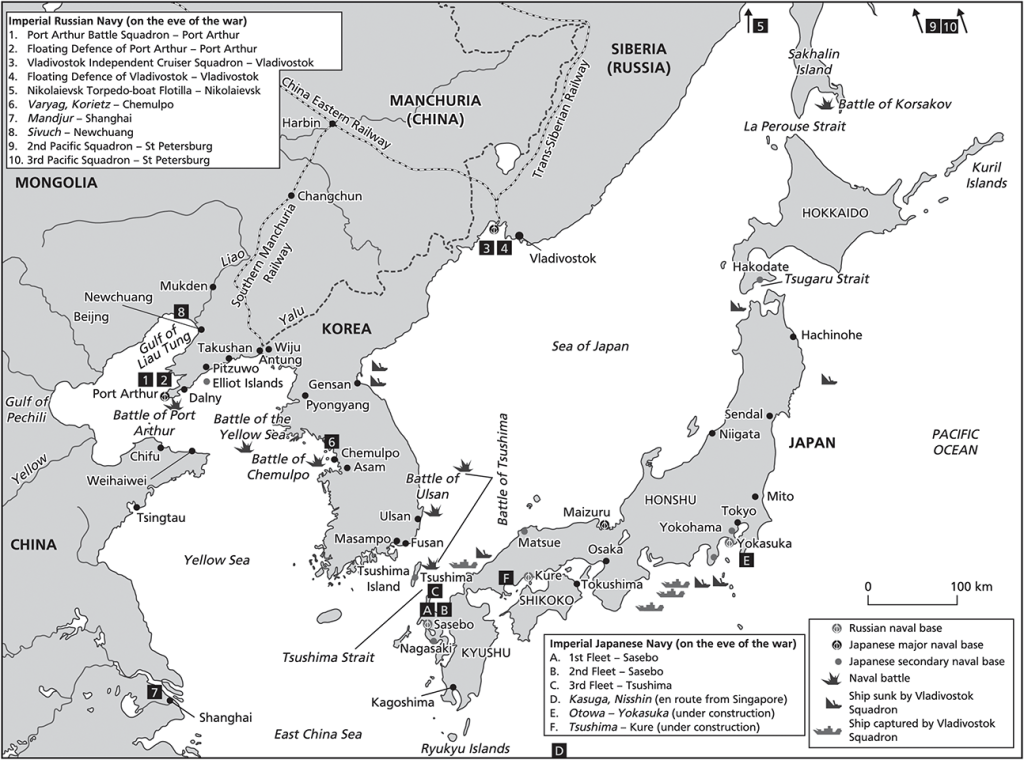

The relative weakness of the Russian squadron was increased by the fact that the war found it divided into three parts: four cruisers (Rurik, Rossiya, Gromoboy, Bogatyr), under the command of Captain (later Rear Adm.) Reitzenstein (later, with Reitzenstein’s transfer to Port Arthur, under the command of Rear Adm. Jessen) were stationed in Vladivostok, the cruiser Varyag was in Chemulpo, and the remaining ships were in Port Arthur. It is much more difficult to determine the mutual relationship of the ground forces.

The total number of the army that Russia can mobilize is several times greater than the Japanese; but Japan could transfer almost its entire army to the theater of war, and it is now impossible to say how great the carrying capacity of the Siberian railway was and how many men Russia could concentrate and feed in Manchuria, which was to become the theater of military operations. The Russian army in Manchuria before the war was no more than tens of thousands of soldiers. Japan had no troops there at all. It is difficult to determine the financial resources that Russia and Japan could have had for the war.

The Russian budget for 1904, which was not prepared for the war, showed a deficit of 195 million rubles, which had to be covered from available cash (312 million rubles). As soon as the war began, a new issue of banknotes was made for 50 million and a reduction in budget estimates was announced by 134 million (of which 75 were from loans for the construction of new railways and the improvement of old ones, 18 from loans for the improvement of waterways). The funds thus compiled could not cover the demands of wartime, since according to the most modest estimates, the war required no less than 50 million rubles. per month, and, in addition, by undermining trade and industry, it had an adverse effect on the receipt of state revenues. Therefore, in the spring of 1904, a 5% loan for 300 million rubles was concluded in Paris, and in August, the issue of a new internal loan for 150 million rubles in six series of 25 million was announced. The fee for passenger tickets in favor of the Red Cross was increased from 5 kopecks to 10 kopecks.

The war immediately had a very serious effect on the economic situation of Russia; many factories had to stop working; the oil industry suffered especially, due to the difficulty of export from the ports of the Black Sea; an exceptionally large number of free workers appeared on the labor market; trade turnover fell sharply. As far as can be judged from the published data, the finances of Russia were affected The first six months of the war were not particularly noticeable. The gold reserves in the treasury and the state bank, which amounted to 899 million on January 1, 1904, and 920 on February 1, began to decrease, but very slowly; by May 1 it had reached 843 million, and at the same time there was an increase in the bank’s liabilities due to the increase in the number of banknotes in circulation.

Then (probably due to the receipt of amounts from the loan) the gold reserves began to increase, although slowly. The amounts lying on the current account of the treasury in the state bank fluctuated, without showing a particularly obvious tendency to decrease. — The state of Japan’s financial resources was less favorable: in addition to three loans (two internal and one external, each for 100 million yen, the latter on very harsh terms: low emission rate, 6%, special guarantee of customs duties), concluded in the first six months of the war, Japan had to resort to a general increase in taxes, some by 3%, others by 5, 10, 20 and more percent. Until January 15, the stock exchange resolutely refused to believe in the imminence of war; Russian rent stood at the rate of 99-99.5 per 100, the Japanese 4% loan at 77-80 per 100.

The aggravation of relations between Japan and Russia in the last third of January produced a general panic on the stock exchange; the Japanese loan fell to 64 (later to 60), Turkish securities fell by 12-14%, even French and English ones by 2-3%; shares of Russian industrial enterprises fell sharply. The war had comparatively little effect on the Russian state rent, which fell to 93 by February 1 (it should be remembered that the South African War had already lowered English securities by 14% in 1900); winning loans fell very sharply (by 100 rubles, i.e. by 20-25%). After the first days of panic, the stock exchange strengthened, funds rose and then stood quite firmly during the first 6 months of the war.

The Russian rent stood at approximately 93 until mid-April. The battle of Tyurenchensk on April 18 led to its rapid fall, reaching 87 with a fraction at the beginning of May, but then a reverse began, and at the end of August, despite all the military failures, it stood again at 92-93. The declaration of war also affected the situation of savings banks: in February 1904, for the first time in many years, the number of savings books decreased by 13,000, and the number of deposits by 7 million (instead of the usual increase of several million). This phenomenon was explained, however, not only by panic (which affected mainly small depositors, with deposits of up to 25 rubles, and only in large cities, i.e., mainly servants, minor employees, etc.), but also by the need for people going to war (officers, doctors) to realize their funds. Already in April, the life of savings banks to some extent approached the conditions of normal times.

The commander-in-chief of all military forces of Russia in the Far East was the Viceroy of the Far East, Adjutant General Alekseyev, whose headquarters at the beginning of the war were in Port Arthur. On February 9, Vice Admiral Makarov was appointed Commander of the Naval Forces, and Commander of the Ground Forces, February 13 – Gen. Kuropatkin (previously the Minister of War); at the end of February the first and in mid-March the second arrived at the theater of military operations. Adm. Togo commanded the Japanese fleet, four land armies – by Generals and Marshals Kuroki, Oku, Nodzu, Nogi; the overall commander-in-chief was appointed only in May – Marshal Oyama. The Japanese General Staff developed a plan for the land campaign that was strikingly similar, sometimes down to the smallest detail, to the plan for the campaign of 1894, and although the resistance of the Russians to the offensive actions of the Japanese was incomparably more serious than the resistance of the Chinese, the battles in the first six months of the war took place in the same places as during the war with China.

The first period of military operations was from January 27 to April 18, 1904; a period of predominantly naval actions and preparatory land operations.

Military operations began on January 27, 1904. The Japanese squadron sailed to the harbor of Port Arthur and on the night of January 27 launched a mine attack on the Russian squadron, as a result of which the battleships Retvizan and Tsesarevich and the cruiser Palladia received holes, which, in the absence of a good dock in Port Arthur, could only be repaired by May. The response to this attack was the Imperial Manifesto of January 27, declaring war. Troops were mobilized first in Siberia, then in several military districts of European Russia. The government message of February 5 emphasized the treachery of Japan and indicated that quick successes could not be expected due to the peculiarities of this war. “The whole situation of the war forces us to patiently await news of the successes of our arms, which may not become apparent until the Russian army begins decisive actions.

Let Russian society patiently await future events, fully confident that our army will make us pay a hundredfold for the challenge thrown down to us.” On the afternoon of January 27, the Japanese squadron bombarded the fortress of Port Arthur and the Russian squadron; both responded. As a result, several Russian ships received minor holes, which were soon repaired. On the same day, January 27, a Japanese squadron of several cruisers, under the command of Admiral Uriu, having entered the harbor of Chemulpo, announced to Captain Rudnev, commander of the cruiser Varyag, about the opening of military operations and proposed that he leave the harbor; a battle began, after which the cruiser Varyag and the gunboat Koreets were destroyed by the Russians themselves; the crew, with the exception of 34 killed, moved to the foreign ships moored there. The damage to the Japanese ships in this battle has not been established with certainty (the Japanese deny it).

On January 29, the mine transport Yenisei, which was laying mines in the harbor, ran into one of them and perished, along with 96 people. Around the same time, the 2nd-rank cruiser Boyarin perished from a similar accident. Thus, the naval campaign began unhappily for us: Port Arthur was blockaded from the sea by Togo’s squadron, the Russian squadron was locked in its harbor and could not go far from the shore, since in the open sea, outside the protection of Port Arthur’s powerful coastal batteries, it was significantly weaker than the Japanese; another squadron, Captain Reitzenstein’s, which was in Vladivostok, was cut off from Port Arthur.

Throughout February, Togo continually began bombarding Port Arthur and the Port Arthur squadron, but without noticeable results, since he did not dare to approach the fortress close for fear of land batteries. Several times he also made attempts to block the entrance to the Port Arthur roadstead, sending his fire ships there and sinking them in the shallow and narrow strait; but if he sometimes succeeded in achieving his goal, then it was far from complete and for a very short time. Only once, namely on April 20, did this bring very significant benefits to the Japanese, facilitating the landing in Bitszywo.

Of the significant number of skirmishes and naval battles at Port Arthur in February and March, which ended without significant results, It is necessary to note the battle of February 26, in which one Japanese destroyer and one Russian (Steregushchiy) perished, with some of the crew of the latter being killed and some taken prisoner. In March, after the arrival of Vice-Admiral Makarova, the Russian squadron began to go out to sea further from the shore. On March 31, a significant battle took place, in which the Russian destroyer “Strashny” perished with almost its entire crew. The admiral’s battleship “Petropavlovsk” ran into a mine (judging by all the data, a Japanese one, laid by the Japanese two days before the battle, and not a Russian one, as was initially thought), exploded and sank in two minutes. Vice-Adm. Makarov, the famous artist V.V. Vereshchagin and about 700 people of the crew perished on it; Grand Prince Kirill Vladimirovich was saved. Another battleship, “Pobeda”, received a large hole in the starboard side from a torpedo, which was repaired only several months later. Vice-Adm. Skrydlov was appointed commander of the fleet in place of Makarov.

The Russian Port Arthur squadron, weakened by this event (in Port Arthur there remained three battleships capable of active operations, with a tonnage of 34,000 and 179 guns, against seven Japanese, with a tonnage of 93,000 and 392 guns), was deprived of the ability to take action for the entire month of April. Jessen’s Vladivostok squadron went out to sea several times and on April 12 sank the Japanese military transport Kinshiyu Maru off the eastern coast of Korea near the city of Genzan, having first taken off 20 officers, 17 lower ranks and non-military personnel, who surrendered; the rest (a significant) part of the crew refused to surrender and preferred to perish. Then, as in its other excursions, the Vladivostok squadron sank Japanese merchant ships, thereby harming its trade.

But this squadron was too weak to prevent the landing of Japanese troops in Korea, primarily in Chemulpo (the nearest harbor to Manchuria, which was already free of ice at the end of January). The landing was carried out under the protection of the powerful squadron of Admiral Togo, with complete safety for the Japanese. Throughout February, March, and perhaps April, the landing of the Japanese army (under the command of General Kuroki) gradually took place, consisting of 5 divisions, including one guard and one reserve (about 128,000 men, with 294 guns). These forces were concentrated in Korea, which thus became the arena of military operations.

The Russians concentrated one corps under the command of General Zasulich on the right (Manchurian) bank of the Yalu River. Only the Cossack brigade under the command of General Mishchenko was sent to Korea to meet the Japanese, which performed more reconnaissance than combat service. Numerous but minor skirmishes with the Japanese occurred between its individual detachments.

The largest of these occurred on March 15 near Chonju (in northwestern Korea) between 6 hundred Cossacks and a somewhat larger Japanese force; after several hours of skirmishing, the Cossacks retreated to the north, with a loss of 4 men killed and 14 wounded (Japanese losses, according to Japanese reports, were approximately the same). On April 12, the Japanese began, under the protection of several gunboats, to cross the Yalu River near its mouth. The crossing, accompanied by battles, lasted almost a week; on April 18, it ended with a major battle between Zasulich’s corps and significantly superior Japanese forces on the right bank of the Yalu River, near Tyurenchen. General Zasulich accepted the battle because, due to an accidental interruption in telegraph communications, he did not receive General Kuropatkin’s order to retreat in time. After stubborn resistance, the Russians retreated to Fenghuangcheng, leaving on the battlefield, according to official data, 26 officers and 564 lower ranks killed, about 700 missing (most of them were probably captured) and more than 1,000 wounded; the total losses were 2,394 people. According to Japanese reports, Japanese losses did not exceed 1,000 killed and wounded. This battle opened the land war, with its theater being transferred from Korea to Manchuria and, simultaneously, to Liaodong.

The second period of the war, mainly on land, the struggle for the Liaodong Peninsula. April 18 – June 25, 1904.

The victory at Tyurencheng gave the Japanese the opportunity to: 1) move west, in the direction of the Eastern Chinese Railway (the Gaizhou-Haicheng-Liaoyang- The second period of the war, mainly on land, the struggle for the Liaodong Peninsula. April 18 – June 25, 1904.

The victory at Tyurencheng gave the Japanese the opportunity to: 1) move west, in the direction of the Eastern Chinese Railway (the Gaizhou-Haicheng-Liaoyang-Mukden section); 2) carry out a landing on the Liaodong Peninsula itself. Naval operations faded into the background, although, in contrast to the first period of Japanese successes at sea, the second was marked by several serious failures. After the Battle of Tyurencheng, the Russians gave the city of Fenghuangcheng to the Japanese without a fight, which became General Kuroki’s headquarters.

The landing on the Liaodong Peninsula began on April 21 at Bizivou (eastern bank); the 2nd Army under the command of General Oku landed; later the 3rd (Nozu) landed near Dakushan (NE), and even later the 4th, which was commanded, it seems, by General Nogi; but soon Marshal Oyama, appointed commander-in-chief, arrived to it, and he directed its actions more than the actions of the other armies. Oku’s army moved to the southwest. On April 29, it occupied the Pulandian railway station and thus cut off from Manchuria the south of the Liaodong Peninsula, with its tip, Kwantung, and the fortress of Port Arthur located on it.

Anticipating the beginning of the siege of Port Arthur, Adjutant General Alekseyev had moved his headquarters to Mukden several days before. A long and stubborn siege of Port Arthur began from the land, accompanied by a blockade from the sea. In Port Arthur there were no wireless telegraph apparatuses or an aeronautical park, so that at first only occasional news came from it through officers and soldiers making their way past the Japanese outposts. On May 1-2, events occurred that weakened the naval blockade. On May 1, the Japanese 2nd rank cruiser Miako, while fishing for mines near the mountains of Dalniy, ran into one of them and perished (the crew was rescued). On May 2, the battleship Hatsuse also perished near Port Arthur, having run into an underwater mine; the cruiser Yoshino received a hole in a collision in the fog with the Japanese ship Kassuga, and also sank; 768 people drowned on both. The battleship Yashima received a hole and was out of action for a long time. On the same day, May 2, the Russian cruiser Bogatyr (of the Vladivostok squadron) ran aground on a reef, from which it was removed only two months later, and the hole has not been repaired to this day (August 20).

Since by May all the Russian ships damaged on January 27 or March 31 had been repaired, with the exception of the Bogatyr, the forces of the two fleets were almost equal from May onwards; the blockade of Port Arthur had become so weak that the Russian squadron under the command of Rear Admiral Vitgeft could go far out to sea, and the destroyer Lieutenant Burakov travelled from Port Arthur to Yingkou and back, bringing information about the situation of the besieged fortress and delivering military supplies to it. Admiral Kamimura’s squadron, which was supposed to monitor the activities of the Vladivostok squadron, was probably weakened by the fact that several ships had been taken from it to reinforce Togo, and therefore was completely inadequate to its task; it did not notice the Vladivostok squadron when it passed close to it, could not keep up with it or simply did not dare to engage it in battle.

Meanwhile, the Vladivostok squadron, especially since the arrival of Admiral Skrydlov (May 9), who, unable to get to Port Arthur, arrived in Vladivostok and raised his flag on the cruiser Rossiya, showed extraordinary energy. It repeatedly went out to sea under the command of Rear Admiral Bezobrazov and made bold raids right up to the shores of Japan, where it sank merchant ships and military transports.

Of greatest significance was the sinking of three transports on June 2 near Iki Island (near Kiu Siu): Itsutsi-maru, Hitachi-maru, Sado-maru with heavy guns for the siege of Port Arthur, with military supplies, with several thousand soldiers, with several million in money. On land at this time, the Japanese were moving forward toward Port Arthur. On May 13, after a stubborn battle that lasted 5 days, General Oku, having 3 divisions at his disposal, took the strong fortification of Jin-Zhou, where there was one Russian division of General Fok. The Japanese lost about 3,500 people killed and wounded, the Russians – over 500 people, 68 guns, 10 machine guns. The capture of Jin-Zhou – on a narrow isthmus connecting the Kwantung Peninsula with Liaodong and the mainland – made the siege of Port Arthur complete.

On May 17, the Japanese occupied Talienwan and Dalniy, abandoned by the Russians, without a fight. Since then, the 4th Army landed on Kwantung under the personal command of Commander-in-Chief Oyama (its numbers are determined very differently according to different sources, probably about 80,000 people), and for many months a regular siege of Port Arthur was conducted.

Meanwhile, General Oku (3 divisions, 81,000 people, 306 guns) gradually moved north, occupying the Liaodong Peninsula. At first, the Russians retreated without a fight, but later General Kuropatkin sent General Stackelberg’s corps to meet the Japanese, which on June 2 encountered General Oku, who had superior forces, at Wafangou, and after a stubborn battle was forced to retreat, having lost several thousand people and a significant number of guns. The Japanese advance northward, slowed by this battle, continued, and on June 25, after a not particularly fierce battle, they occupied the city of Gaizhou (Gaiping). Thus, the occupation of the Liaodong Peninsula was completed; only Port Arthur held out, successfully repelling attacks from land and sea.

In Manchuria, at the same time, the armies of Kuroki (5 divisions, 128,000 men, 294 guns) and Nodzu (4 divisions, 92,000 men, 182 guns) slowly, enduring a series of battles, advanced toward the railroad line. On June 12-14, Kuroki rather easily occupied the Fynshuilin, Modulin, and Motienlin mountain passes, lying on the roads to Liaoyang, Haichen, and Mukden; on June 21 and 22, he successfully repelled Russian attacks on them. He also occupied the cities of Samadzy and Syaosyr. Nodzu occupied Xiuyan. Thus, three Japanese armies, in contact with each other, occupied all of Liaodong and the entire southeast of Manchuria.

The number of forces at the disposal of General Kuropatkin is unknown especially since the arrival of Admiral Skrydlov (May 9), who, unable to get to Port Arthur, arrived in Vladivostok and raised his flag on the cruiser Rossiya, showed extraordinary energy. He repeatedly went to sea under the command of Rear Admiral Bezobrazov and made bold raids all the way to the shores of Japan, where she sank merchant ships and military transports. Of greatest significance was the sinking of three transports, carried out on June 2 near Iki Island (near Kiu Siu): Itsutsi-maru, Hitachi-maru, Sado-maru with heavy guns for the siege of Port Arthur, with military supplies, with several thousand soldiers, with several million in money.

The third period of the war. The struggle for the Liaohe River valley and for Port Arthur, beginning on June 26, 1904.

On July 4, the Russians (Count Keller) attacked the Motienlin Pass, but were repulsed, with losses of over 1,000 men; after a stubborn battle on July 5-6, in which the Russians also lost no less than 1,000 men, the Japanese captured the city of Siheyan. On July 10-11, a very important battle took place between Gaizhou and Dashiqiao, the most significant since the beginning of the war in terms of the number of forces involved (according to Japanese reports – 5 Russian divisions, 3 Japanese divisions, according to Russian news – less), surpassing in this respect the three previous major battles (Tyurenchen, Jing-Zhou, Wafangou). The enormous losses on both sides are determined differently. As a result, the Russians cleared Dashiqiao. The days of July 12-19 were a continuous battle, moving from the south (Dashitsyao – Haicheng) to the east (passes) of the Manchurian theater of military operations and back. Russian losses are estimated at several thousand people killed; Japanese losses are somewhat less. The Russians lost several guns.

On July 18, Count Keller was killed at the Yangzelinsky Pass. As a result of these battles, the Japanese occupied Newzhuang and Yingkou. The occupation of the port of Yingkou provided a very important naval base, much closer to the active army than Bizivuo and Dagushan, and therefore facilitated their movement to Liaoyang.

On July 19, Haicheng was occupied by the Japanese. In the naval battle of July 13 near Port Arthur, in which four of our first-rank cruisers took part against three Japanese first-rank cruisers and two second-rank cruisers, one of our cruisers (Bayan) and two Japanese (Itsuku-ima and Chiyoda; the first of them was repaired a week later) were disabled.

From July 13 to 15, the Japanese stormed some of the forts of Port Arthur, which were repulsed with great losses for them. At the end of July, they managed to occupy Wolf Mountains (Lunwangtian), Green Mountain and some forts; in August, several forts were taken, and in mid-August, the Japanese stood only 1.5 miles from the fortress itself. Nevertheless, the garrison of the fortress under the command of General Stessel, despite heavy losses, courageously repelled all Japanese assaults.

The possible fall of Port Arthur, which would inevitably have been followed by the death of our squadron if it had remained in the roadstead, forced the Russians to think about saving it. On July 28, the entire squadron capable of active operations under the command of Admiral Vitgeft, consisting of 6 battleships, 4 cruisers (except for the “Bayan”, which had been badly damaged on July 13), 8 destroyers and several auxiliary vessels, went to sea, intending to break through the enemy ring and join up with the Vladivostok squadron.

The goal, however, was not achieved, since in the battle that followed on the very day of July 28, the squadron was defeated, and Admiral Vitgeft, who commanded it, was killed. Five battleships, the cruiser Palladia and 3 destroyers were forced to return to Port Arthur. The remaining ships, badly damaged, broke through, but had to take refuge in neutral harbors: German Kiao Chau, Chinese Wuzong (near Shanghai), French Saigon (Indochina), where they were forced to disarm; the disarmed crew was settled on the territory of neutral states until the end of the war. The cruiser Novik successfully broke through, but on August 8 it was overtaken by Japanese cruisers off Sakhalin Island and sunk; another destroyer was lost.

The counter-destroyer Reshitelny, independently of the rest of the squadron, arrived on July 28 in Chifoo with important dispatches; in view of the Japanese readiness to attack it even in a neutral harbor, it was blown up by the Russians, however, it did not sink, and was captured by the Japanese in a damaged state. This incident gave rise to a dispute between Russia and Japan about the violation of international law. On August 1, the Vladivostok squadron, consisting of three cruisers, under the command of Rear Admiral Jessen, left to meet the Port Arthur squadron, and collided with Admiral Kamimura’s squadron (6 cruisers) off the coast of Korea. As a result of the stubborn battle, the cruiser Rurik sank, and the other two cruisers with serious holes and damaged engines and pipes took refuge in Vladivostok. Thus, the entire Pacific squadron (with the exception of two cruisers Rossiya and Gromoboy that were saved from destruction in this battle, albeit with damage, and the cruiser Bogatyr, which had been damaged earlier) either perished completely or was disarmed and, consequently, perished for the real war. The death of the squadron made it easier for the Japanese to storm Port Arthur, which, however, stubbornly resists to this day (October 15, 1904).

From August 11 to 15, a series of serious battles took place to the east and south of Liaoyang, as a result of which the Japanese occupied Anping, Anipangjian, Liandianxiang, and thus tightened the semicircle surrounding Liaoyang from the west, south, and east. On August 16, a battle began near Liaoyang itself, where General Kuropatkin’s 6 corps (about 250,000 men) were concentrated. Three armies (Kuroki, Oku, and Nozu), probably numbering about 250,000, were attacking it from three sides. After a series of bloody battles from August 17 to 20, Admiral General Kuropatkin cleared Liaoyang on August 21, which was occupied by the Japanese on August 22. The Russians’ clearing of Liaoyang was caused by the transition of Kuroki’s army to the right bank of the river on August 16. Taizykh with the aim of bypassing the left flank of the Russians and cutting off their retreat to Mukden. By August 23, General Kuropatkin’s entire army had gathered between Mukden and Telin, facing the armies of Oku and Nodzu from the south and southwest and the army of Kuroki from the east and northeast. After the Battle of Liaoyang, a lull set in in the Manchurian theatre of war.

On September 19, General Kuropatkin gave the order to advance and from September 23 to 26 moved his main forces to Yantai, while sending a strong detachment to the southeast across the Taizykh River to bypass the Japanese right flank. From September 27 to October 3, a series of fierce and bloody battles took place, fought with varying fortunes. At first, the Japanese had the upper hand, managing to knock out several regiments on the Russian right flank, capture several batteries and break through the Russian centre. On September 30, the Russians retreated to the northern bank of the Shakhe River; the outflanking of the Japanese right flank by the Russian eastern detachment was unsuccessful. In the battles of October 1-3, the Russians managed to push back the Japanese center, take two batteries and fortify part of their positions on the southern bank of the Shakhe, after which a lull set in again. Russian losses from September 23 to October 3 were about 40 thousand. The Japanese – slightly less. In early September, the formation of the 2nd Manchurian Army under the command of General Grippenberg was announced, and on October 12, General Kuropatkin was appointed commander-in-chief of all Russian land and sea forces in the Far East. At the end of September, the 2nd Pacific Squadron under the com-mand of Vice-Admiral Rozhestvensky left for the Far East.

From the point of view of military technology, the first six months of the Ya.-Russian war revealed the following phenomena: 1) the general opinion was that improved weapons of destruction would make the war especially bloody. This expectation was not justified: not a single battle in terms of bloodshed resembled Austerlitz, Borodino, Leipzig, Waterloo, Solferino, etc. The battles are fought at too great a distance, and the means of defense have improved in proportion to the attack. 2) The wounds caused by improved guns heal for the most part easily, at least with good care, in any case better than wounds inflicted by previous rifle bullets. This is explained by the small caliber of the bullets and the terrible speed of their flight (700 meters per second). Bullet wounds received at a greater distance are more dangerous than wounds received at close range. On the contrary, the effect of cannon grenades is deadly. 3) Submarines have not yet been used in real war.

During this third period the first Russian Pacific squadron perished (July 28, 1904). Communication between the Japanese army on the Asian continent and Japan became completely easy; supplies from Japan no longer presented any difficulties. The situation of the Russian army, whose communications with the homeland were hampered by the enormous distance and the low carrying capacity of the railway, was very sad. The army commander, General Kuropatkin, constantly promised victories and demanded patience from the army and from Russian society, but at the same time retreated soon after orders to the army, in which he said that “the long-desired time has come to go meet the enemy and force the Japanese to obey our will” (September 18).

The battle of September 24 – October 3 on the southern bank of the Shake River had no definite result, since both sides remained approximately in their previous positions; but in terms of the number of victims and the consequences it was more a victory for the Japanese than for the Russians. On October 12, General Kuropatkin was appointed commander-in-chief of all Russian land and sea forces in the Far East in place of Alekseyev. After the battle, a long lull set in in the northern theatre of military operations; the Japanese did not dare to go on the offensive, and the Russians therefore had no need to retreat.

The whole world followed the struggle near Port Arthur with even greater attention. Almost deprived of naval support (the ships locked in its bay were mostly damaged and, in any case, could not act) and unable to count on reinforcements from the north, besieged from land and sea by the strong land army of General Nogi and the strong fleet of Admiral Togo, this fortress was doomed to surrender, but it resisted stubbornly. In Russia and Europe, the credit for this defense was attributed to General Stoessel; but later, after the fortress had been taken, it became clear that it was General Stoessel who was responsible for the fortress being completely unprepared for defense, and for the disorder that prevailed there.

In December 1904, the military council in Port Arthur decided to surrender the fortress. According to available information, this decision was made by General Stoessel himself and carried through the military council by means of strong pressure on the officers, but not without protests. On December 20, the capitulation was signed. By virtue of this capitulation, the entire garrison of Port Arthur and the entire crew of the squadron that had landed on land were recognized as prisoners of war; the officers were allowed to return to Russia on condition that they pledged not to participate in the war; all batteries, surviving ships, ammunition, horses, and all government buildings were sur-rendered to the Japanese. The number of those taken prisoners was 70,000 people (half of whom were wounded and sick), including 8 generals and 4 admirals. The Japanese also took a significant amount of coal, provisions, and military supplies. As for the fleet, only the most pitiful remnants of it fell into the hands of the Japanese, since most of the ships in the bay and saved from the Japanese cannonade were promptly sunk by the Russians themselves. Some of them were subsequently raised from the bottom of the bay by the Japanese, repaired and entered the Japanese navy.

The capture of Port Arthur ended the third period of the war. During the first year of the war, up to 200,000 people left the Russian army killed, wounded and captured, in addition, about 25,000 were sick; 720 guns and almost the entire first Pacific squadron were lost. The Japanese losses in people were no less, but the Japanese fleet was almost not damaged, the artillery was strengthened by the capture of Russian guns.

The fourth period of the war. From the capture of Port Arthur to the destruction of the second Russian squadron at Tsushima, December 20, 1904 – May 14, 1905.

After the fall of Port Arthur, the entire Liaodong Peninsula was in Japanese hands and General Nogi’s army could be sent north to help other Japanese armies. In the north, the lull that had begun after the battle on the Shahe River was still continuing. Two formidable armies stood opposite each other; the so-called secrets of the Russians and Japanese were separated from each other in places by 150-200 paces; nevertheless, neither the Japanese nor the Russians went on the offensive.

At the end of December 1904, General Mishchenko made a bold raid on Yingkou, i.e., far into the rear of the Japanese army. This raid did not have a positive significance: Mishchenko’s detachment was discovered and pushed back to the western bank of the Liaohe River, which in the eyes of the Japanese, and even more so the Chinese, was considered Chinese territory, inviolable for war; as a result, General Mishchenko’s retreat along the right bank of the Liaohe gave the Japanese a reason to raise a protest against Russia’s violation of international law. General Mishchenko only managed to burn several Japanese warehouses. On January 12-16, a rather significant battle took place between General Grippenberg’s army and the Japanese. The former attacked the fortified village of Sandepu and entered its unfortified part, but soon had to withdraw, having lost no less than 12,000 people killed and wounded and 2,000 captured (Japanese losses are estimated at 7,000 people).

Kuropatkin accused Grippenberg of imprudence, Grippenberg accused Kuro-patkin of not supporting him at the decisive moment. Gripienberg resigned his command and went to St. Petersburg. At the end of January, near Gunchzhulin, significantly north of Mukden, far in the rear of the Russian army, a detachment of Japanese and Honghuzi was discovered. A small detachment of border guards was sent against them, under the command of Captain Le-nitsky; he encountered 6 squadrons and 4 companies of Japanese and over 2,000 Honghuzi and only with great difficulty and significant losses managed to break through. The Japanese man-aged to damage the railway bridge and the telegraph line over a significant distance. On February 11-25, 1905, a terrible battle took place near Mukden.

The Russian army, having suffered very heavy losses, was forced to retreat hastily and in disarray. In Mukden, the Japanese captured enormous food supplies, hospitals with 1,600 of our wounded, and barracks with Japanese who had been captured by us. According to official data, the losses in killed and wounded on the Japanese side were only 41,000, while according to private data, they were 50 or 60,000. The Japanese army was so exhausted that it was unable to pursue the Russians. The entire Liaohe River valley, the battle for which had begun on June 26, 1904, was in Japanese hands.

The road to Girin and Harbin was open to them. The immediate result of the battle was the resignation of General Kuropatkin from the rank of commander-in-chief, which he received on March 3. In his place was appointed General Linevich, who had commanded the 1st Manchurian Army, and Kuropatkin took his place. Around the same time, General Kaulbars was appointed in place of General Grippenberg, who commanded the 11th Manchurian Army, and the latter’s place, who commanded the 3rd Army, was first taken by General Bilderling, then, a few days later, by General Batyanov. The Japanese did not find it necessary or possible to go on the offensive, and after the Battle of Mukden, the same menacing lull began as after the Battle of Shahe. The armies stood opposite each other near Gongzhulin and were only preparing for the coming battle.

General attention was again turned to the naval theater of military operations. As early as October 1904, the second Pacific squadron under the command of Vice-Admiral Rozhestvensky left the Baltic Sea. On April 26, it was joined by the 3rd squadron, on February 2, which left Libau under the command of Rear Admiral Nebogatov. But this joining did not strengthen, but weakened Rozhestvensky’s squadron, since it consisted of old, slow and unfit for combat ships, which were a burden, slowing down the movements and activities of the second squadron. Rozhestvensky himself was decisively against sending a third squadron, but it was the result of agitation for its dispatch, raised by Novoye Vremya and in it by Captain Klado. Rozhestvensky even made an attempt to avoid a meeting with Nebogatov, but the attempt failed, the squadrons merged, and Nebogatov came under Rozhestvensky’s command.

On May 14, the combined squadrons clashed near the island of Tsushima with the squadron of Admiral Togo. As a result of the battle, which lasted several hours, most of Admiral Rozhestvensky’s ships sank, and several ships surrendered. Admirals Rozhestvensky and Nebogatov were also captured. Only one 2nd-rank cruiser, the Almaz, and two counter-destroyers managed to break through to Vladivostok. About 7,000 people died, and about 6,000 people were captured. The monetary value of the lost ships is estimated at 150-200 million rubles. The Japanese squadron got off with the loss of only three destroyers and more or less significant, but repairable damage to several battleships and cruisers. Thus, the Battle of Tsushima was a catastrophe, far surpassing Mukden in its significance.

The fifth period of the war, from Tsushima to the conclusion of peace. May 15 – August 23, 1905.

On May 26, 1905, US President Roosevelt addressed a note to Russia and Japan proposing to stop further bloodshed and begin peace negotiations. Both sides accepted the proposal. On July 20, Russian envoys, Chairman of the Committee of Ministers S. Yu. Witte and Russian Ambassador to the United States of America Baron Rosen, and Japanese envoys, Minister of Foreign Affairs Baron Komura and Minister to the United States of America Takahira, arrived in the United States.

On July 27, negotiations began in Portsmouth. Both sides initially displayed considerable stubbornness; several times it seemed that the negotiations would be broken off. Roosevelt used all his influence to persuade the parties to be more accommodating. Finally, on August 23 (O.S.), peace was signed. The Japanese renounced their original demands—a war contribution, the surrender of all Russian warships that had taken refuge from Japanese pursuit in foreign ports, the cession of all of Sakhalin, and the granting to the Japanese of full fishing rights along the Russian coasts of the Pacific Ocean.

Russia recognized Japan’s predominant political, military, and economic interests in Korea and pledged not to interfere with such measures of direction, patronage, and supervision as the Japanese government might deem necessary to take in Korea. Russia and Japan pledged to evacuate Manchuria completely and simultaneously, with the exception of the Liaodong Peninsula, which would pass into Japanese possession on the same lease basis on which it had formerly belonged to Russia.

Manchuria would be returned to China. The railroad between Kuan-chen-tzu and Port Arthur would pass to Japan without compensation, together with all its property and the coal mines developed for the benefit of the railroad. Russia and Japan undertake to exploit the railways belonging to them in Manchuria exclusively for commercial and industrial purposes, but in no way for strategic purposes; this does not extend to the railways on the Liaotung Peninsula. Russia cedes to Japan the southern half of Sakhalin up to 50° latitude.

Prisoners of war are to be mutually returned, with Russia obliged to compensate Japan for the difference between the amount of expenses incurred by Japan for the maintenance of Russian prisoners and the amount incurred by Russia for the maintenance of Japanese prisoners. The remaining articles establish a mutual obligation to respect the rights of private property, outline the commercial and fishing agreements to be concluded, and speak of the restoration of peace and friendship. Japan thus received the most valuable part of Sakhalin in full possession, the Liaodong Peninsula with Port Arthur in leasehold possession, Korea, which finally became its vassal, and a significant part of Manchuria, through which the Japanese rail-way, received without compensation, passes, in actual possession.

The war dealt a strong blow to Russia’s political power and made Japan an equal member in the concert of European and American powers and at the same time a very serious rival of the United States in the Pacific Ocean. This is the main political result of the war from the point of view of international relations. On December 22, 1905, a Japanese-Chinese treaty was concluded, which was the completion of the Russo-Japanese treaty. By virtue of this treaty, Japan was obliged to return Manchuria to China, and China recognized the transfer of Liaodong and part of the railroad into the hands of Japan and transferred to the Japanese government the very same concession for the exploitation of forests on the right bank of the Yalu, which had previously belonged to Bezobrazov’s company. The monetary cost of the war has not yet been accurately calculated. Russia’s state debt in-creased by 2 billion rubles; this is its approximate cost for Russia. For Japan it is lower.

section); 2) carry out a landing on the Liaodong Peninsula itself. Naval operations faded into the background, although, in contrast to the first period of Japanese successes at sea, the second was marked by several serious failures. After the Battle of Tyurencheng, the Russians gave the city of Fenghuangcheng to the Japanese without a fight, which became General Kuroki’s headquarters.

The landing on the Liaodong Peninsula began on April 21 at Bizivou (eastern bank); the 2nd Army under the command of General Oku landed; later the 3rd (Nozu) landed near Dakushan (NE), and even later the 4th, which was commanded, it seems, by General Nogi; but soon Marshal Oyama, appointed commander-in-chief, arrived to it, and he directed its actions more than the actions of the other armies. Oku’s army moved to the southwest. On April 29, it occupied the Pulandian railway station and thus cut off from Manchuria the south of the Liaodong Peninsula, with its tip, Kwantung, and the fortress of Port Arthur located on it.

Anticipating the beginning of the siege of Port Arthur, Adjutant General Alekseyev had moved his headquarters to Mukden several days before. A long and stubborn siege of Port Arthur began from the land, accompanied by a blockade from the sea. In Port Arthur there were no wireless telegraph apparatuses or an aeronautical park, so that at first only occasional news came from it through officers and soldiers making their way past the Japanese outposts. On May 1-2, events occurred that weakened the naval blockade. On May 1, the Japanese 2nd rank cruiser Miako, while fishing for mines near the mountains of Dalniy, ran into one of them and perished (the crew was rescued). On May 2, the battleship Hatsuse also perished near Port Arthur, having run into an underwater mine; the cruiser Yoshino received a hole in a collision in the fog with the Japanese ship Kassuga, and also sank; 768 people drowned on both. The battleship Yashima received a hole and was out of action for a long time. On the same day, May 2, the Russian cruiser Bogatyr (of the Vladivostok squadron) ran aground on a reef, from which it was removed only two months later, and the hole has not been repaired to this day (August 20).

Since by May all the Russian ships damaged on January 27 or March 31 had been repaired, with the exception of the Bogatyr, the forces of the two fleets were almost equal from May onwards; the blockade of Port Arthur had become so weak that the Russian squadron under the command of Rear Admiral Vitgeft could go far out to sea, and the destroyer Lieutenant Burakov travelled from Port Arthur to Yingkou and back, bringing information about the situation of the besieged fortress and delivering military supplies to it. Admiral Kamimura’s squadron, which was supposed to monitor the activities of the Vladivostok squadron, was probably weakened by the fact that several ships had been taken from it to reinforce Togo, and therefore was completely inadequate to its task; it did not notice the Vladivostok squadron when it passed close to it, could not keep up with it or simply did not dare to engage it in battle.

Meanwhile, the Vladivostok squadron, especially since the arrival of Admiral Skrydlov (May 9), who, unable to get to Port Arthur, arrived in Vladivostok and raised his flag on the cruiser Rossiya, showed extraordinary energy. It repeatedly went out to sea under the command of Rear Admiral Bezobrazov and made bold raids right up to the shores of Japan, where it sank merchant ships and military transports.

Of greatest significance was the sinking of three transports on June 2 near Iki Island (near Kiu Siu): Itsutsi-maru, Hitachi-maru, Sado-maru with heavy guns for the siege of Port Arthur, with military supplies, with several thousand soldiers, with several million in money. On land at this time, the Japanese were moving forward toward Port Arthur. On May 13, after a stubborn battle that lasted 5 days, General Oku, having 3 divisions at his disposal, took the strong fortification of Jin-Zhou, where there was one Russian division of General Fok. The Japanese lost about 3,500 people killed and wounded, the Russians – over 500 people, 68 guns, 10 machine guns. The capture of Jin-Zhou – on a narrow isthmus connecting the Kwantung Peninsula with Liaodong and the mainland – made the siege of Port Arthur complete.

On May 17, the Japanese occupied Talienwan and Dalniy, abandoned by the Russians, without a fight. Since then, the 4th Army landed on Kwantung under the personal command of Commander-in-Chief Oyama (its numbers are determined very differently according to different sources, probably about 80,000 people), and for many months a regular siege of Port Arthur was conducted.

Meanwhile, General Oku (3 divisions, 81,000 people, 306 guns) gradually moved north, occupying the Liaodong Peninsula. At first, the Russians retreated without a fight, but later General Kuropatkin sent General Stackelberg’s corps to meet the Japanese, which on June 2 encountered General Oku, who had superior forces, at Wafangou, and after a stubborn battle was forced to retreat, having lost several thousand people and a significant number of guns. The Japanese advance northward, slowed by this battle, continued, and on June 25, after a not particularly fierce battle, they occupied the city of Gaizhou (Gaiping). Thus, the occupation of the Liaodong Peninsula was completed; only Port Arthur held out, successfully repelling attacks from land and sea.

In Manchuria, at the same time, the armies of Kuroki (5 divisions, 128,000 men, 294 guns) and Nodzu (4 divisions, 92,000 men, 182 guns) slowly, enduring a series of battles, advanced toward the railroad line. On June 12-14, Kuroki rather easily occupied the Fynshuilin, Modulin, and Motienlin mountain passes, lying on the roads to Liaoyang, Haichen, and Mukden; on June 21 and 22, he successfully repelled Russian attacks on them. He also occupied the cities of Samadzy and Syaosyr. Nodzu occupied Xiuyan. Thus, three Japanese armies, in contact with each other, occupied all of Liaodong and the entire southeast of Manchuria.

The number of forces at the disposal of General Kuropatkin is unknown especially since the arrival of Admiral Skrydlov (May 9), who, unable to get to Port Arthur, arrived in Vladivostok and raised his flag on the cruiser Rossiya, showed extraordinary energy. He repeatedly went to sea under the command of Rear Admiral Bezobrazov and made bold raids all the way to the shores of Japan, where she sank merchant ships and military transports. Of greatest significance was the sinking of three transports, carried out on June 2 near Iki Island (near Kiu Siu): Itsutsi-maru, Hitachi-maru, Sado-maru with heavy guns for the siege of Port Arthur, with military supplies, with several thousand soldiers, with several million in money.

The third period of the war. The struggle for the Liaohe River valley and for Port Arthur, beginning on June 26, 1904.

On July 4, the Russians (Count Keller) attacked the Motienlin Pass, but were repulsed, with losses of over 1,000 men; after a stubborn battle on July 5-6, in which the Russians also lost no less than 1,000 men, the Japanese captured the city of Siheyan. On July 10-11, a very important battle took place between Gaizhou and Dashiqiao, the most significant since the beginning of the war in terms of the number of forces involved (according to Japanese reports – 5 Russian divisions, 3 Japanese divisions, according to Russian news – less), surpassing in this respect the three previous major battles (Tyurenchen, Jing-Zhou, Wafangou). The enormous losses on both sides are determined differently. As a result, the Russians cleared Dashiqiao. The days of July 12-19 were a continuous battle, moving from the south (Dashitsyao – Haicheng) to the east (passes) of the Manchurian theater of military operations and back. Russian losses are estimated at several thousand people killed; Japanese losses are somewhat less. The Russians lost several guns.

On July 18, Count Keller was killed at the Yangzelinsky Pass. As a result of these battles, the Japanese occupied Newzhuang and Yingkou. The occupation of the port of Yingkou provided a very important naval base, much closer to the active army than Bizivuo and Dagushan, and therefore facilitated their movement to Liaoyang.

On July 19, Haicheng was occupied by the Japanese. In the naval battle of July 13 near Port Arthur, in which four of our first-rank cruisers took part against three Japanese first-rank cruisers and two second-rank cruisers, one of our cruisers (Bayan) and two Japanese (Itsuku-ima and Chiyoda; the first of them was repaired a week later) were disabled.

From July 13 to 15, the Japanese stormed some of the forts of Port Arthur, which were repulsed with great losses for them. At the end of July, they managed to occupy Wolf Mountains (Lunwangtian), Green Mountain and some forts; in August, several forts were taken, and in mid-August, the Japanese stood only 1.5 miles from the fortress itself. Nevertheless, the garrison of the fortress under the command of General Stessel, despite heavy losses, courageously repelled all Japanese assaults.

The possible fall of Port Arthur, which would inevitably have been followed by the death of our squadron if it had remained in the roadstead, forced the Russians to think about saving it. On July 28, the entire squadron capable of active operations under the command of Admiral Vitgeft, consisting of 6 battleships, 4 cruisers (except for the “Bayan”, which had been badly damaged on July 13), 8 destroyers and several auxiliary vessels, went to sea, intending to break through the enemy ring and join up with the Vladivostok squadron.

The goal, however, was not achieved, since in the battle that followed on the very day of July 28, the squadron was defeated, and Admiral Vitgeft, who commanded it, was killed. Five battleships, the cruiser Palladia and 3 destroyers were forced to return to Port Arthur. The remaining ships, badly damaged, broke through, but had to take refuge in neutral harbors: German Kiao Chau, Chinese Wuzong (near Shanghai), French Saigon (Indochina), where they were forced to disarm; the disarmed crew was settled on the territory of neutral states until the end of the war. The cruiser Novik successfully broke through, but on August 8 it was overtaken by Japanese cruisers off Sakhalin Island and sunk; another destroyer was lost.

The counter-destroyer Reshitelny, independently of the rest of the squadron, arrived on July 28 in Chifoo with important dispatches; in view of the Japanese readiness to attack it even in a neutral harbor, it was blown up by the Russians, however, it did not sink, and was captured by the Japanese in a damaged state. This incident gave rise to a dispute between Russia and Japan about the violation of international law. On August 1, the Vladivostok squadron, consisting of three cruisers, under the command of Rear Admiral Jessen, left to meet the Port Arthur squadron, and collided with Admiral Kamimura’s squadron (6 cruisers) off the coast of Korea. As a result of the stubborn battle, the cruiser Rurik sank, and the other two cruisers with serious holes and damaged engines and pipes took refuge in Vladivostok. Thus, the entire Pacific squadron (with the exception of two cruisers Rossiya and Gromoboy that were saved from destruction in this battle, albeit with damage, and the cruiser Bogatyr, which had been damaged earlier) either perished completely or was disarmed and, consequently, perished for the real war. The death of the squadron made it easier for the Japanese to storm Port Arthur, which, however, stubbornly resists to this day (October 15, 1904).

From August 11 to 15, a series of serious battles took place to the east and south of Liaoyang, as a result of which the Japanese occupied Anping, Anipangjian, Liandianxiang, and thus tightened the semicircle surrounding Liaoyang from the west, south, and east. On August 16, a battle began near Liaoyang itself, where General Kuropatkin’s 6 corps (about 250,000 men) were concentrated. Three armies (Kuroki, Oku, and Nozu), probably numbering about 250,000, were attacking it from three sides. After a series of bloody battles from August 17 to 20, Admiral General Kuropatkin cleared Liaoyang on August 21, which was occupied by the Japanese on August 22. The Russians’ clearing of Liaoyang was caused by the transition of Kuroki’s army to the right bank of the river on August 16. Taizykh with the aim of bypassing the left flank of the Russians and cutting off their retreat to Mukden. By August 23, General Kuropatkin’s entire army had gathered between Mukden and Telin, facing the armies of Oku and Nodzu from the south and southwest and the army of Kuroki from the east and northeast. After the Battle of Liaoyang, a lull set in in the Manchurian theatre of war.

On September 19, General Kuropatkin gave the order to advance and from September 23 to 26 moved his main forces to Yantai, while sending a strong detachment to the southeast across the Taizykh River to bypass the Japanese right flank. From September 27 to October 3, a series of fierce and bloody battles took place, fought with varying fortunes. At first, the Japanese had the upper hand, managing to knock out several regiments on the Russian right flank, capture several batteries and break through the Russian centre. On September 30, the Russians retreated to the northern bank of the Shakhe River; the outflanking of the Japanese right flank by the Russian eastern detachment was unsuccessful. In the battles of October 1-3, the Russians managed to push back the Japanese center, take two batteries and fortify part of their positions on the southern bank of the Shakhe, after which a lull set in again. Russian losses from September 23 to October 3 were about 40 thousand. The Japanese – slightly less. In early September, the formation of the 2nd Manchurian Army under the command of General Grippenberg was announced, and on October 12, General Kuropatkin was appointed commander-in-chief of all Russian land and sea forces in the Far East. At the end of September, the 2nd Pacific Squadron under the com-mand of Vice-Admiral Rozhestvensky left for the Far East.

From the point of view of military technology, the first six months of the Ya.-Russian war revealed the following phenomena: 1) the general opinion was that improved weapons of destruction would make the war especially bloody. This expectation was not justified: not a single battle in terms of bloodshed resembled Austerlitz, Borodino, Leipzig, Waterloo, Solferino, etc. The battles are fought at too great a distance, and the means of defense have improved in proportion to the attack. 2) The wounds caused by improved guns heal for the most part easily, at least with good care, in any case better than wounds inflicted by previous rifle bullets. This is explained by the small caliber of the bullets and the terrible speed of their flight (700 meters per second). Bullet wounds received at a greater distance are more dangerous than wounds received at close range. On the contrary, the effect of cannon grenades is deadly. 3) Submarines have not yet been used in real war.

During this third period the first Russian Pacific squadron perished (July 28, 1904). Communication between the Japanese army on the Asian continent and Japan became completely easy; supplies from Japan no longer presented any difficulties. The situation of the Russian army, whose communications with the homeland were hampered by the enormous distance and the low carrying capacity of the railway, was very sad. The army commander, General Kuropatkin, constantly promised victories and demanded patience from the army and from Russian society, but at the same time retreated soon after orders to the army, in which he said that “the long-desired time has come to go meet the enemy and force the Japanese to obey our will” (September 18).

The battle of September 24 – October 3 on the southern bank of the Shake River had no definite result, since both sides remained approximately in their previous positions; but in terms of the number of victims and the consequences it was more a victory for the Japanese than for the Russians. On October 12, General Kuropatkin was appointed commander-in-chief of all Russian land and sea forces in the Far East in place of Alekseyev. After the battle, a long lull set in in the northern theatre of military operations; the Japanese did not dare to go on the offensive, and the Russians therefore had no need to retreat.

The whole world followed the struggle near Port Arthur with even greater attention. Almost deprived of naval support (the ships locked in its bay were mostly damaged and, in any case, could not act) and unable to count on reinforcements from the north, besieged from land and sea by the strong land army of General Nogi and the strong fleet of Admiral Togo, this fortress was doomed to surrender, but it resisted stubbornly. In Russia and Europe, the credit for this defense was attributed to General Stoessel; but later, after the fortress had been taken, it became clear that it was General Stoessel who was responsible for the fortress being completely unprepared for defense, and for the disorder that prevailed there.

In December 1904, the military council in Port Arthur decided to surrender the fortress. According to available information, this decision was made by General Stoessel himself and carried through the military council by means of strong pressure on the officers, but not without protests. On December 20, the capitulation was signed. By virtue of this capitulation, the entire garrison of Port Arthur and the entire crew of the squadron that had landed on land were recognized as prisoners of war; the officers were allowed to return to Russia on condition that they pledged not to participate in the war; all batteries, surviving ships, ammunition, horses, and all government buildings were sur-rendered to the Japanese. The number of those taken prisoners was 70,000 people (half of whom were wounded and sick), including 8 generals and 4 admirals. The Japanese also took a significant amount of coal, provisions, and military supplies. As for the fleet, only the most pitiful remnants of it fell into the hands of the Japanese, since most of the ships in the bay and saved from the Japanese cannonade were promptly sunk by the Russians themselves. Some of them were subsequently raised from the bottom of the bay by the Japanese, repaired and entered the Japanese navy.

The capture of Port Arthur ended the third period of the war. During the first year of the war, up to 200,000 people left the Russian army killed, wounded and captured, in addition, about 25,000 were sick; 720 guns and almost the entire first Pacific squadron were lost. The Japanese losses in people were no less, but the Japanese fleet was almost not damaged, the artillery was strengthened by the capture of Russian guns.

The fourth period of the war. From the capture of Port Arthur to the destruction of the second Russian squadron at Tsushima, December 20, 1904 – May 14, 1905.

After the fall of Port Arthur, the entire Liaodong Peninsula was in Japanese hands and General Nogi’s army could be sent north to help other Japanese armies. In the north, the lull that had begun after the battle on the Shahe River was still continuing. Two formidable armies stood opposite each other; the so-called secrets of the Russians and Japanese were separated from each other in places by 150-200 paces; nevertheless, neither the Japanese nor the Russians went on the offensive.

At the end of December 1904, General Mishchenko made a bold raid on Yingkou, i.e., far into the rear of the Japanese army. This raid did not have a positive significance: Mishchenko’s detachment was discovered and pushed back to the western bank of the Liaohe River, which in the eyes of the Japanese, and even more so the Chinese, was considered Chinese territory, inviolable for war; as a result, General Mishchenko’s retreat along the right bank of the Liaohe gave the Japanese a reason to raise a protest against Russia’s violation of international law. General Mishchenko only managed to burn several Japanese warehouses. On January 12-16, a rather significant battle took place between General Grippenberg’s army and the Japanese. The former attacked the fortified village of Sandepu and entered its unfortified part, but soon had to withdraw, having lost no less than 12,000 people killed and wounded and 2,000 captured (Japanese losses are estimated at 7,000 people).

Kuropatkin accused Grippenberg of imprudence, Grippenberg accused Kuro-patkin of not supporting him at the decisive moment. Gripienberg resigned his command and went to St. Petersburg. At the end of January, near Gunchzhulin, significantly north of Mukden, far in the rear of the Russian army, a detachment of Japanese and Honghuzi was discovered. A small detachment of border guards was sent against them, under the command of Captain Le-nitsky; he encountered 6 squadrons and 4 companies of Japanese and over 2,000 Honghuzi and only with great difficulty and significant losses managed to break through. The Japanese man-aged to damage the railway bridge and the telegraph line over a significant distance. On February 11-25, 1905, a terrible battle took place near Mukden.

The Russian army, having suffered very heavy losses, was forced to retreat hastily and in disarray. In Mukden, the Japanese captured enormous food supplies, hospitals with 1,600 of our wounded, and barracks with Japanese who had been captured by us. According to official data, the losses in killed and wounded on the Japanese side were only 41,000, while according to private data, they were 50 or 60,000. The Japanese army was so exhausted that it was unable to pursue the Russians. The entire Liaohe River valley, the battle for which had begun on June 26, 1904, was in Japanese hands.

The road to Girin and Harbin was open to them. The immediate result of the battle was the resignation of General Kuropatkin from the rank of commander-in-chief, which he received on March 3. In his place was appointed General Linevich, who had commanded the 1st Manchurian Army, and Kuropatkin took his place. Around the same time, General Kaulbars was appointed in place of General Grippenberg, who commanded the 11th Manchurian Army, and the latter’s place, who commanded the 3rd Army, was first taken by General Bilderling, then, a few days later, by General Batyanov. The Japanese did not find it necessary or possible to go on the offensive, and after the Battle of Mukden, the same menacing lull began as after the Battle of Shahe. The armies stood opposite each other near Gongzhulin and were only preparing for the coming battle.

General attention was again turned to the naval theater of military operations. As early as October 1904, the second Pacific squadron under the command of Vice-Admiral Rozhestvensky left the Baltic Sea. On April 26, it was joined by the 3rd squadron, on February 2, which left Libau under the command of Rear Admiral Nebogatov. But this joining did not strengthen, but weakened Rozhestvensky’s squadron, since it consisted of old, slow and unfit for combat ships, which were a burden, slowing down the movements and activities of the second squadron. Rozhestvensky himself was decisively against sending a third squadron, but it was the result of agitation for its dispatch, raised by Novoye Vremya and in it by Captain Klado. Rozhestvensky even made an attempt to avoid a meeting with Nebogatov, but the attempt failed, the squadrons merged, and Nebogatov came under Rozhestvensky’s command.

On May 14, the combined squadrons clashed near the island of Tsushima with the squadron of Admiral Togo. As a result of the battle, which lasted several hours, most of Admiral Rozhestvensky’s ships sank, and several ships surrendered. Admirals Rozhestvensky and Nebogatov were also captured. Only one 2nd-rank cruiser, the Almaz, and two counter-destroyers managed to break through to Vladivostok. About 7,000 people died, and about 6,000 people were captured. The monetary value of the lost ships is estimated at 150-200 million rubles. The Japanese squadron got off with the loss of only three destroyers and more or less significant, but repairable damage to several battleships and cruisers. Thus, the Battle of Tsushima was a catastrophe, far surpassing Mukden in its significance.

The fifth period of the war, from Tsushima to the conclusion of peace. May 15 – August 23, 1905.

On May 26, 1905, US President Roosevelt addressed a note to Russia and Japan proposing to stop further bloodshed and begin peace negotiations. Both sides accepted the proposal. On July 20, Russian envoys, Chairman of the Committee of Ministers S. Yu. Witte and Russian Ambassador to the United States of America Baron Rosen, and Japanese envoys, Minister of Foreign Affairs Baron Komura and Minister to the United States of America Takahira, arrived in the United States.

On July 27, negotiations began in Portsmouth. Both sides initially displayed considerable stubbornness; several times it seemed that the negotiations would be broken off. Roosevelt used all his influence to persuade the parties to be more accommodating. Finally, on August 23 (O.S.), peace was signed. The Japanese renounced their original demands—a war contribution, the surrender of all Russian warships that had taken refuge from Japanese pursuit in foreign ports, the cession of all of Sakhalin, and the granting to the Japanese of full fishing rights along the Russian coasts of the Pacific Ocean.

Russia recognized Japan’s predominant political, military, and economic interests in Korea and pledged not to interfere with such measures of direction, patronage, and supervision as the Japanese government might deem necessary to take in Korea. Russia and Japan pledged to evacuate Manchuria completely and simultaneously, with the exception of the Liaodong Peninsula, which would pass into Japanese possession on the same lease basis on which it had formerly belonged to Russia.

Manchuria would be returned to China. The railroad between Kuan-chen-tzu and Port Arthur would pass to Japan without compensation, together with all its property and the coal mines developed for the benefit of the railroad. Russia and Japan undertake to exploit the railways belonging to them in Manchuria exclusively for commercial and industrial purposes, but in no way for strategic purposes; this does not extend to the railways on the Liaotung Peninsula. Russia cedes to Japan the southern half of Sakhalin up to 50° latitude.

Prisoners of war are to be mutually returned, with Russia obliged to compensate Japan for the difference between the amount of expenses incurred by Japan for the maintenance of Russian prisoners and the amount incurred by Russia for the maintenance of Japanese prisoners. The remaining articles establish a mutual obligation to respect the rights of private property, outline the commercial and fishing agreements to be concluded, and speak of the restoration of peace and friendship. Japan thus received the most valuable part of Sakhalin in full possession, the Liaodong Peninsula with Port Arthur in leasehold possession, Korea, which finally became its vassal, and a significant part of Manchuria, through which the Japanese rail-way, received without compensation, passes, in actual possession.

The war dealt a strong blow to Russia’s political power and made Japan an equal member in the concert of European and American powers and at the same time a very serious rival of the United States in the Pacific Ocean. This is the main political result of the war from the point of view of international relations. On December 22, 1905, a Japanese-Chinese treaty was concluded, which was the completion of the Russo-Japanese treaty. By virtue of this treaty, Japan was obliged to return Manchuria to China, and China recognized the transfer of Liaodong and part of the railroad into the hands of Japan and transferred to the Japanese government the very same concession for the exploitation of forests on the right bank of the Yalu, which had previously belonged to Bezobrazov’s company. The monetary cost of the war has not yet been accurately calculated. Russia’s state debt in-creased by 2 billion rubles; this is its approximate cost for Russia. For Japan it is lower.

Autore: Vasily Vasilyevich Vodovozov (Василий Васильевич Водовозов

Fonte: Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary 1908 (Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона)

Lascia un commento