What is the army rear?

Every state in a war with another puts up huge armies to defend its borders, in the ranks of which there are hundreds of thousands and millions of fighters. All this huge mass of people must be clothed, fed, properly armed. This requires a huge amount of food, fodder, uniforms – clothes, shoes, weapons: rifles, machine guns, cannons, armored cars, airplanes, wire and various building materials for trenches, etc.

To this we must add that during battles, countless quantities of metal are produced and spoiled, i.e. cartridges, shells, bombs, grenades, etc.

Of course, every state must prepare for war in advance. Before the war, it must prepare the necessary supplies for the war, bring them somewhere closer to the border and store them in well-equipped warehouses and stores, so that the army has them at hand in case of war. If this or that state does not do this, then its cause will be lost. In the first days of the war, the army will be left without ammunition, weapons and bread. It will not be able to fight and will have to surrender to the mercy of the winner. Therefore, during the war, all factories and plants producing military equipment, weapons, ammunition, work even harder than in peacetime.

But producing is not enough. Everything produced must be distributed, and most importantly, transported to the fronts and supplied to the troops in time. Therefore, it is clear what a huge importance railways have during a war. The more of them are built to the border of that state, the sooner it will be possible to transfer all the reinforcements and cargo necessary for the troops, and therefore, the better these troops will be supplied and armed. Such an army, which does not need anything, will fight steadfastly, bravely and will defeat the enemy. All this work on preparing everything necessary for the war and on delivering it to the front is what is called the work of the rear. The correct and successful work of the front depends on the correctness, precision and continuity of this work – from the commander to the fighter.

The army, stretched for hundreds of thousands of miles along the front, is led by headquarters – military institutions that are connected with the troops by telegraph, telephone, and radio. By telegraph and telephone, army headquarters quickly issue orders and receive reports on everything that is happening at the front. The headquarters also manage the army’s supplies and the necessary warehouses for the most essential military equipment. The headquarters, with their entire network of institutions, with all their communications, constitute the so-called immediate rear of the front, the head of the front, its brain. And therefore it is especially important that their work proceeds calmly, confidently, and without interference.

Thus, both the front and the rear during war represent a single whole, and any damage or malfunction of the rear is reflected at the front, and a penalty at the front is often reflected in the work of the rear.

How to understand a cavalry raid

Due to this importance of the rear, it is clear that to destroy the enemy’s rear or to disrupt its continuous work for at least a few days often means to disarm the enemy. That is why in almost all wars each of the warring parties takes great care of its rear and at the same time tries to spoil the work of the enemy’s rear.

Various means of damaging this work are now being used. Entire squadrons (detachments) of airplanes can be sent into the enemy’s rear, where they destroy railway stations, bridges, and warehouses with bombs. There were individual brave partisans (volunteers), acting at their own risk, deeply devoted to the cause of their state, who secretly made their way into the enemy’s rear and blew up railway tracks and warehouses there, delaying and complicating the work of the enemy’s rear.

However, the enemy vigilantly guards its rear. At each station, especially where there are warehouses, at each railway bridge, at each large military headquarters there is always a strong guard, there are special guns for shooting at airplanes. If individual partisans managed to cause some destruction and an airplane to drop several bombs on one place, then it had little significance. The enemy quickly dealt with this destruction, strengthening its guard and defense in places dangerous to it.

In order to truly disarm the enemy, it is necessary to cause as much destruction as possible, and to do it over a large area. Only cavalry can do this task.

Cavalry, with its mobility and strength, can suddenly break through the enemy’s front or bypass one of his flanks into his deep rear, stay in his rear for several days, or even a week, and step by step destroy enemy headquarters, ammunition and food depots, railway bridges, air stations, telegraphs, etc. along the way. At the same time, it can fight with the enemy’s defense, with his troops and artillery, which neither airplanes nor individual partisans can do.

An enemy army with a destroyed rear over a large area cannot resist for long. Without control, the supply of everything necessary, expecting an attack from the rear by enemy cavalry at any moment, such an army quickly disintegrates and turns to flight.

Such actions of cavalry in the enemy’s rear are called a raid or a foray. For the greatest clarity of understanding of what a raid is, we will give several examples from our civil war of 1918-1920 and other wars.

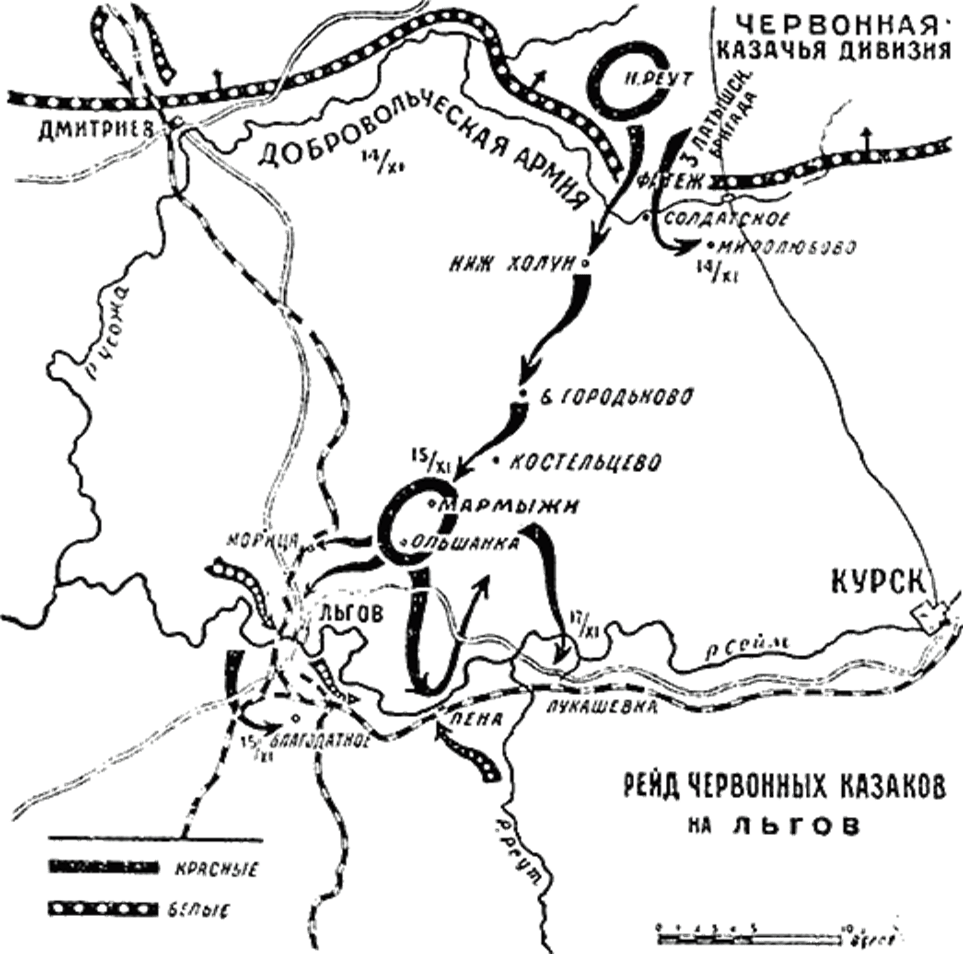

Raid of the 8th Red Cavalry Division (Figure 1)

In early November 1919, General Kutepov’s White Guard corps fortified itself along the line of the Vozy-Fatezh station and the Usozh-Dmitriev rivers (Figure 1). Our infantry units, despite stubborn fighting, could not dislodge the Whites. The Whites went on the offensive and began to push back our infantry units.

Then the commander of the 14th Red Army orders the commander of the 8th Red Cossack Division to break through to the area of the city of Fatezh and destroy the railway junction in the city of Lgov with a quick strike. The White Guards brought everything they needed for the battle through this junction and therefore guarded it well. To destroy Lgov meant to disarm the corps of General Kutepov.

On November 14, at dawn, our rifle units launched an offensive and broke through the White front in the area of the village of Soldatskoye. The 8th Cavalry Division slipped through this gap unnoticed in a severe snowstorm and quickly moved toward Lgov.

It was difficult to move because a strong snowstorm was raging, covering the road and blinding the eyes. However, this snowstorm was also to the advantage of the red cavalry, since it covered all tracks and hid the cavalry’s movement from the enemy. The division moved in one column along one road. Passing through the villages, the red cavalrymen spread the rumor that the whites were defeated, that they had little time left to live.

The village picked up these rumors about the defeat of the Whites and reported them to the entire White army. These rumors frightened the soldiers and officers. Unrest began in the remote villages. The peasants, counting on the imminent arrival of the Red Army, began to kill individual White Guard officers and destroy entire small detachments.

And the Red Cavalry went – regiment after regiment – deeper and further into the enemy’s rear, overcoming mountains, descents, ascents. The Red Army soldiers themselves pulled out the guns on the ascents by hand. On one ascent, a gun, which had been pulled almost to the top of the mountain, suddenly rolled down and pulled the Red Army soldiers along with it.

A huge lump of men and steel rushed down a steep icy mountain. With a roar, the entire mass fell to the bottom of the ravine. Several people were badly bruised, one had his legs cut off. But new platoons were rushing to replace them, and the gun was dragged up the mountain by another route, through broken fences and vegetable gardens.

The division moved on. The road was difficult. The men and horses were exhausted. The storm did not subside. The division, despite having many reliable and loyal guides, lost its way several times. However, these difficulties did not dampen the courage and vigor of the fighters.

The division advanced boldly and confidently and by the morning of November 15 occupied the villages of Olshanka, Marmyshi, and Kosteltsevo. That same day, the division covered 50 km. In the village of Olshanka, a supply train and a machine gun crew of 100 white men, 8 Maxim tanks, and 40 carts were captured without resistance from the unexpected appearance of the Red enemy. The officers were drunk and did not quickly understand what was going on. From the officers, the division chief, Comrade Primakov, learned that General Mai-Maevsky’s army headquarters and many echelons (trains) with property were located in the city of Lgov.

The appearance of the Red cavalry in the rear of the Whites was a complete surprise; therefore, Comrade Primakov decided to immediately capture Lgov station. At 9 a.m. on November 15, on his orders, the division launched an attack on Lgov from different sides. The snowstorm was getting worse. But the 2nd brigade of the division under the command of Comrade Krityak, approaching Lgov station, instead of immediately taking it by air, opened artillery fire. The locomotives immediately began to smoke, and General Mai-Maevsky’s headquarters left the station. The shooting was a mistake that allowed Mai-Maevsky to escape.

After a short artillery preparation, the brigade broke into the city and began to cut down the enemy infantry crowded in the street. The latter tried to resist, but it was too late. Lgov was taken. Two railway bridges and a station were destroyed, up to 200 wagons of property, uniforms, a large convoy, 800 prisoners, and 5 guns were captured.

The enemy units that were at the front knew nothing about the Red raid, that they were already in their rear, and the loss of communication with Lvov was explained by the storm that was still raging at that time. The Whites’ only routes of retreat were through Lgov. Therefore, Comrade Primakov decided to give the division a rest in the Lgov area and at the same time lie in wait for the Whites’ retreat. In order to keep an eye on the Whites, patrols were sent to the front to instill more fear in the enemy and to definitely take prisoners.

Indeed, the patrols accomplished their tasks: they captured prisoners and made such a noise that the enemy, frightened by the appearance of the Red cavalry in the rear, tried only to escape as quickly as possible. But these attempts were in vain.

Having settled in the Lgov-Marmyshi area, the 8th Cavalry Division intercepted retreating units, defeated them and captured them.

In this struggle, on November 17, a platoon of red cavalry encountered an enemy battalion during reconnaissance. The Whites were heading for Kosteltsevo and, not expecting an attack from anywhere, they put their weapons, rifles and machine guns on peasant carts. The carts were half a mile behind and were moving with little cover. The platoon commander decided to try his luck and capture the convoy.

The platoon rode up to the wagon train. The platoon commander, wearing the shoulder straps of a captain, which he had put on so that the Whites would not recognize him, started a conversation with the cover commander, a young ensign. The platoon prepared for battle and then, shouting “Hurray!”, rushed at the Whites. The cover was cut down. There were 400 rifles in the wagon train. Thus the White battalion was disarmed.

A snowstorm covered up the traces of this disarmament and drowned out the cries of battle. The White battalion did not know that its weapons had already been taken away, and safely arrived in Kosteltsevo without weapons, where by evening the entire 2nd White Regiment had grouped, of which one battalion was without rifles. The regiments of the 8th Cavalry Division, having opened fire on them, attacked the enemy from three sides; the village was occupied. Up to 1,000 prisoners and 2 guns were captured.

On November 18, the division cut off 5 armored trains retreating to Lgov from Kursk.

Thus the 8th Cavalry Division smashed the rear and the retreating Whites, and thanks to the raid the enemy was finally defeated along the entire front and retreated in disarray 150 kilometers to the south.

During the entire raid, the cavalry captured 17,000 prisoners, 36 guns, 5 armored trains, 200 wagons with uniforms, up to 50 machine guns, and up to 500 people were killed.

Raid on Fatezh – Ponyri (Figure 2)

In the autumn of 1919, Denikin’s forces defeated the Red Army on the banks of the Don and pursued it from Kharkov to Orel [1] . The Red Army units, disorganized, exhausted, and tired, retreated north. In the rear, everything had been destroyed by General Mamontov’s cavalry, the railways were undamaged, and the warehouses with food supplies had been burned. Some Soviet commanders from among the former officers, thinking that the Reds had been completely defeated, betrayed them and went over to the White camp. Mistrust of their commanders grew among the Red Army soldiers. And, as is well known, an army without commanders or with traitorous commanders cannot hold out for long.

The Red Army was going through a difficult time. The Whites had already captured Orel and were preparing to march on Moscow. It was necessary to gather the last of their forces and at all costs repel the enemy. For this purpose, the Latvian Division, together with the cavalry brigade of Comrade Primakov, was ordered to take Orel. The Latvian Division, together with the cavalry, accomplished this. With a dashing blow, the Whites were driven out of Orel. The enemy suffered heavy losses and retreated to the line of the villages of Eropkipo – Retyazh – Lamovets – Chern – Dmitriev (see Figure 2).

However, the victory did not come cheap. The Latvian division lost about two thousand fighters killed and wounded. Meanwhile, the enemy recovered and went on the offensive.

The Red units were exhausted in the unequal struggle. The head of the Latvian division asked the army commander for help. The situation became very serious, and therefore the army commander himself, comrade Uborevich, and the member of the Revolutionary Military Council, comrade Ordzhonikidze, arrived at the scene of the battle.

At the commanders’ conference they said: “The enemy is getting stronger, and the Red units are weakened and tired; the best command staff has been knocked out of action; if help is not quickly provided, the enemy will take Orel again.” The army commander acquainted the commanders with the general situation at the front, saying that it was impossible to provide help now. It was necessary to fight and win with the forces that were available.

Then Comrade Primakov, who at that time commanded a cavalry brigade, made the following proposal: break through the enemy front and send a cavalry brigade through it on a raid in order to destroy the enemy rear and help our units defeat the Kornilov and Drozdov divisions from the front: Comrade Primakov’s proposal was accepted.

At the same time, it was decided to begin an offensive from the front – at the Dyachaya station, where the enemy headquarters and warehouses were located (see figure 2).

The infantry was supposed to break through the White front in the area of the village of Chern-Chernodye and thereby pave the way for the cavalry to the rear.

The division commander of the 8th Red Division explained the situation and the task to the Red Army soldiers: “Don’t be afraid of encirclement – sabers will cut through any ring. Pass yourself off as General Shkuro’s White Division, remove the stars, put on shoulder straps and call the commanders by rank, explain to the peasants along the way that we are Shkuro’s men, retreating from the front and that the Reds will soon arrive and there will be Soviets everywhere.”

The Red Army soldiers were all burning with the desire to liberate Ukraine, their homeland, from the Whites. “Give us Ukraine!” they shouted.

Early in the morning of November 3, the riflemen approached the village of Chern-Chernodye unnoticed by the enemy without firing a shot, and drove the enemy out with one bayonet strike. The Red Division rushed through this gap into the enemy’s rear. The division went through a forest and a field without roads to hide its movement from the enemy. Along the way, the division captured supply trains, separate small units of the Whites, and blew up bridges across rivers. The Red Army soldiers explained to the residents: “We are the Shkurovites, we are retreating, the Reds are coming after us.” From here, the division sent regiments to various points and destroyed the Ponyri and Vozy stations, captured Fatezh and destroyed the White units there, took up to 100 prisoners, 2 guns and 2 tanks.

On November 3–4, the division covered 130 miles, destroyed 6 White companies, an artillery convoy, 2 guns, 2 armored tractors, 1 echelon with uniforms, and destroyed the Orel–Kursk railways in 16 places. This rout of the White rear by daring cavalry raids caused panic among the enemy troops at the front. The Whites began to retreat hastily. A rumor was spread among the troops that there were 10,000 Red cavalrymen in the rear.

On November 5, the Red Division moved from Olkhovatka to the Dyachaya station to help the Latvian riflemen defeat the Whites from the rear. On the way, reconnaissance reported that the headquarters of the 1st Kornilov Regiment with a small cover was located in the village of Tagin. The division commander ordered an attack on the village of Tagin. The first cavalry regiment approached the village in mounted formation. The Red cavalrymen captured the village with a dashing attack. In the village of Tagin, the office of the 1st Kornilov Regiment was captured, the adjutant was killed, 260 infantrymen were hacked to pieces. The regiment commander with the banner, under the cover of an officer company, managed to escape into the forest.

The division stopped to spend the night after the battle at the Tagin station. Patrols were sent out, which established contact with their infantry.

After this, the cavalry division, together with the riflemen, pursued the whites.

On November 6, in the village of Saburovka, the Kornilov officer regiment was surrounded and destroyed; 7 guns were captured.

Thus, the raid of the 8th Cavalry Division corrected the difficult situation at the front. The Boyka of the 14th Red Army took heart and went on the offensive. The enemy retreated 100 kilometers deep in fear. During this time, the cavalry captured 9 guns, 1,200 prisoners, and destroyed many parts of the supply train.

Raid of Comrade Budyonny’s cavalry (Figure 3)

In the autumn of 1919, the Whites were already approaching Tula and were almost certain that they would soon take Moscow. In order to besiege the presumptuous enemy, the commander of the southern front of the Red Army decided to strike at the enemy’s rear in the direction of Voronezh-Kharkov-Rostov. To carry out this task, Budyonny’s 1st Cavalry Corps, the future Cavalry Army, was assigned, which had by that time been transferred to Voronezh.

Budyonny’s cavalry defeated the cavalry corps of General Shkuro and then Mamontov in turn, after which it rushed into the enemy’s rear towards Kursk (see figure 3).

At the same time, the Red Army went on the offensive from the front; the enemy, pressed from the front and rear, began to retreat in disarray to the south, to the sea.

During these continuous actions of the 1st Cavalry Corps in the rear of Denikin’s forces, 11 thousand prisoners, 33 guns, 170 machine guns and 7 tanks were taken. Many white divisions, such as Markov’s, were almost entirely destroyed.

But the most important thing is that the White Guards cleared the Donets Basin, which was so necessary for the industry of Soviet Russia.

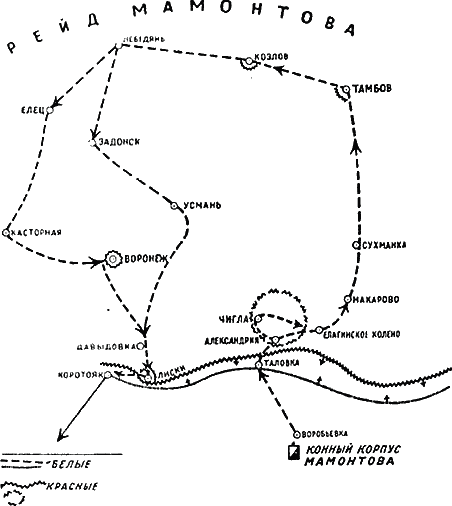

Raid of Mamontov’s Corps (Figure 4)

Cavalry raids lead to great successes. However, these successes and victories of the cavalry in raids will only be useful when they are supported by an offensive from the front. If this is not the case, then the enemy’s rear can be greatly destroyed, and they can be thrown into disarray, but there will be little benefit from this. The enemy will quickly repair everything that has been destroyed, repair the railways and bring in everything they need – ammunition, weapons, reinforcements of military units, food – and go on the offensive. This is how General Mamontov’s raid in August 1919, which, fortunately for us, was not supported by an offensive from the front, ended without any benefit for the White generals.

In the summer of 1919, the Red Army retreated under pressure from the White Guards. The Whites, in order to finally defeat the Red Army, decided to send General Mamontov’s cavalry corps to the rear.

The corps was given the task of destroying railway stations and warehouses around Tambov and Kozlov, Yelets and Voronezh, destroying headquarters and raising a peasant rebellion against Soviet power. For this purpose, the corps was transferred to Uryupinskaya station. The corps had 9,000 horsemen with 12 guns and several armored vehicles.

On August 7, the corps moved toward Novokhopyorsk, broke through the Red front at Talovaya Station, and headed deep into the Red lines toward Tambov. Along the way, General Mamontov’s corps did not encounter strong resistance. Only near Tambov did a battle with the Red units occur. However, the rear units of the Red Army, most of which were not yet trained, were incapable of stubborn defense, and so Tambov was taken by the Whites. In the battles near Tambov, General Mamontov captured many units, including more than 10,000 reserves. They were all sent home. In Tambov itself, the White Guards carried out a large-scale robbery and pogrom. They robbed everyone: government institutions and civilians.

Robberies, violence, and shootings of workers and peasants in the city caused indignation and hatred among the population towards the White Guards.

Continuing to move further, the Mamontovites fought a battle with the Red units on the way to the city of Kozlov. The Red regiments, however, were defeated and scattered due to their small numbers. Kozlov was occupied. The headquarters of the southern front of the Reds left the city in due time. In Kozlov, the Cossacks did not spare a single Soviet institution, a single school, or a single hospital. The city was guarded by the Whites from former officers who assisted General Mamontov in robberies, searches of civilians, and executions of all those suspected of sympathizing with the Soviet government.

After taking Kozlov, the White Corps moved to the Lebedyan station, and from there by two roads: the main forces went through Zadonsk, Usman and Davydovka, and the 10th White Division was sent through Yelets, Kastorvaya and Voronezh. However, the Red command at this time was already convinced that Mamontov’s cavalry was acting completely without communication with the rest of the White Guard front, which did not support the White general’s raid in any way. Therefore, it was decided to cut off his retreat to his own, and Red units began to gather near Voronezh. Strong resistance was put up against the Whites approaching Voronezh. They were repulsed, and their attempt to blow up the railway bridge here failed. Then Mamontov’s men rushed to the station. Here too, the Liskis tried to destroy the station and bridges, but were also repulsed by the already approaching Red units, and in the battle the White corps suffered heavy losses and retreated in disarray to Korotoyan, where it joined up with its front, missing more than half of its original complement and exhausting its entire horse complement.

Mamontov’s raid caused enormous destruction in the rear of the Red armies. Railroad bridges and warehouses were destroyed and burned; reserve troops that were preparing for the front were dispersed. Soviet institutions were destroyed, and many responsible officials and workers were shot. But the White Guards did not take advantage of the success of their cavalry. Due to their weakness, they could not go on the offensive with the cavalry. The Red front was unshakable, although the rear was destroyed. The peasants and workers of the cities and villages through which General Mamontov passed, burning everything in his path and shooting thousands of innocent people, understood what the Whites wanted and firmly stood up for the defense of Soviet power.

The rear was soon restored, and the Red Army went on the offensive.

Cavalry raids are difficult and extremely dangerous affairs. Only a detachment whose fighters are brave, courageous and have boundless trust in their commander can successfully carry them out.

The cavalry commander in a raid is of great importance in itself: he must not only be brave and courageous but also have a good understanding of military affairs. For every mistake made by a cavalry detachment commander, he will have to pay with the blood of his soldiers. The Red Army cavalry had great success in raids because it had such leaders as comrades Budyonny, Kotovsky, Primakov, etc.

The Whites also had their own experienced horsemen-leaders, which is why they had great success in raids. Where the cavalry commanders were out of place, the raid was unsuccessful.

In addition, it is necessary to ensure that the horse train is in good condition and is ready for long marches. If 50-70 km in a raid is considered normal marches for cavalry in a day, if the cavalry in a raid has to cover hundreds of miles in 5-7 days without rest, then it is clear that commanders and soldiers need to very carefully prepare their horses for a long road full of dangers.

All horses must be shod, and the sick ones must be separated from the detachment, otherwise they will only hinder the speed of the cavalry. And the success of the raid depends on this.

Thanks to its mobility, the cavalry can appear unexpectedly for the enemy, where it wants, and conduct any battle. For this purpose, the cavalry is given technical means: artillery, armored vehicles, but in such quantities that all this does not hinder the mobility of the cavalry. The convoy with food and forage is usually not taken, and the cavalry feeds at the expense of local residents. Of course, all the food must be paid for, otherwise discontent and even peasant uprisings against the detachment may arise.

A cavalry raid is carried out according to a specific, pre-developed plan. What is the essence of the plan? A raid plan, as in any business, comes down first of all to outlining the raid’s goals and routes of movement. The immediate goals of a raid, as we already know, are: the destruction of the enemy’s rear and the raising or supporting of a rebellion of the population, if it is dissatisfied with the existing government.

The routes of movement must be chosen so that they are the shortest and hidden from the enemy. Since the objectives of the raid on the way to them lie through the enemy front, the plan must also develop the following question: how to get to the enemy rear. Is it necessary to break through the enemy front, where and how?

All these questions of the plan can be developed only when we know the enemy well, where and how he is located, what is in his rear.

Where can one get such information? Intelligence serves these purposes: military, air and agent (secret messengers to the enemy camp). Secret intelligence is especially difficult, through sending loyal and brave people to the enemy camp. And such people did exist. Often during the civil war, Red Army soldiers were called in, who, disguised as peasants, on a cart or with only a whip, got into the enemy’s rear and found out everything they needed about him. When White Guards they met asked: “Where are you going or going?” – the brave men always answered: “I’m going home, I was in the baggage train” or “I’m going to look for a horse taken by some soldier.”

Based on detailed information about the enemy, a raid plan is drawn up.

The development of the plan is carried out in the strictest secrecy, for which the order for the raid is usually given just before the action, or during the campaign. The secrecy of the preparation of the plan is one of the most important conditions for its success. Failure to observe secrecy, the talkativeness of commanders and Red Army soldiers can ruin the whole thing. Let us give an example of how not to prepare a raid.

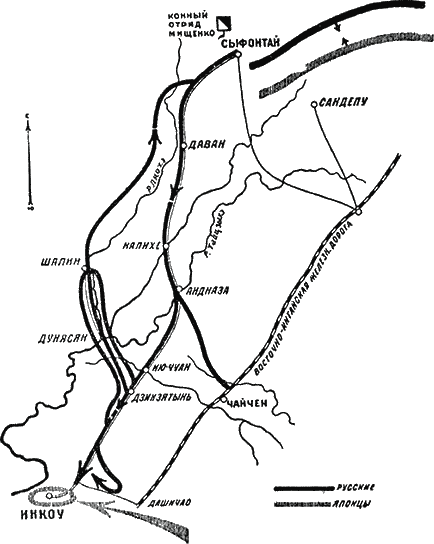

Raid of General Mishchenko’s detachment on Inkou during the Russo-Japanese War in December 1904 (Figure 5)

After the battle between the Russian army and the Japanese on the Shahe River, there was a lull at the front. At that time, the Japanese took Port Arthur and therefore General Nogi’s army was transferred from there to help its main forces by rail through Liaoyang. It is clear that this was not in the interests of the Russians. It was necessary to prevent this transfer at all costs.

How to do this? It was necessary to destroy the railway going to Liaoyang.

But the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian army, General Kuropatkin, did not understand this and decided to destroy not the railway, but the port (sea pier) of Yinkou. The port of Yinkou was of no importance at that winter time, since it was freezing, and the Japanese had not brought anything through it for a long time. There had been no warehouses there for a long time. There was nothing to destroy. This was General Kuropatkin’s mistake. Thanks to it, a raid on a city that had no importance was appointed, and a detachment of General Mishchenko was appointed to the raid. The detachment included 69 hundreds, approximately 8 thousand horsemen (sabres), 22 guns and 4 machine guns. In addition, the detachment was given a huge transport, 1,500 packs with forage and food. This transport was completely unnecessary. There was plenty of forage and food in this area without it, and the captured pack transport only tied the detachment hand and foot.

The preparation of the detachment for the raid was not hidden by anyone. They talked about it several months before and wrote to Petersburg. Long before the performance, farewell parties and farewell dinners began to take place. Priests held farewell prayers. It is quite clear that the Japanese learned about such preparations and immediately removed all their supplies from Yinkou, and strengthened the security there.

On December 26, General Mishchenko’s detachment approached the Syfontai area, on the right flank of his army. From here, the detachment set out along the road to Dawan-Kalihe, New-Chuan, and Inkou. The detachment’s movement was very slow, because the transport was constantly lagging behind, and the detachment had to stop, wait for its supply trains, and pull them up. Along the way, the detachment was constantly engaging in battle with small Japanese units, which further delayed the movement. The distance to Inkou was small—125 miles. But since the cavalry detachment moved at a speed of 20–30 miles, Mishchenko only approached Inkou on December 30, i.e., the march to Inkou lasted 3 days. The detachment fought very sluggishly in the battle for Inkou. Instead of immediately attacking the city and capturing it, General Mishchenko arranged a 3-hour rest 10 miles from the station. The railway was not cut off in time, so the Japanese had the opportunity to bring in reinforcements and repulsed all Russian attacks. The detachment retreated after intense artillery fire. It did not fulfill its mission: the railway, along which the Japanese transported their troops to help the front, remained intact.

This example serves as proof of how not to carry out a raid. There was no secret to the preparation of the raid, the detachment was overworked by transport, which delayed the movement, so the Japanese managed to transfer troops to fight the Russian detachment, and the raid ended in vain.

From the examples given, it is clear that cavalry can only penetrate into the enemy’s rear by breaking through his front. In order to preserve the strength and freshness of a detachment going on a raid, it is better for infantry or units not participating in the raid to break through the enemy’s front. The breakthrough is made suddenly and decisively. Sluggish actions will only prolong the battle and give the enemy a chance to bring up reinforcements, which is the same as immediately disrupting the planned raid. As soon as a breakthrough is formed, the cavalry must immediately slip through these gates and move into the enemy’s rear. The cavalry in the rear must move as quickly and covertly as possible. To this end, the cavalry will have to choose remote roads, often at night, in order to hide its movement from airplanes. Night marches are dangerous because you can lose your way or – even worse – run into a stronger enemy. To avoid this, detachments must have guides and reliable security. In occupied points, each fighter must maintain the strictest discipline. Drunkenness and plundering of the population is the death of a cavalry unit. There are many examples of this. Thus, during the civil war of the North American states, one of the units of the northerners, having penetrated into the rear of the enemy (the southerners), plundered wine warehouses, and the fighters began to drink. Thanks to this, the unit of the southerners overtook them and captured them without any resistance.

We saw the same thing in General Mamontov’s raid. General Mamontov wanted to raise a peasant rebellion against the Soviet power in the rear of the Reds. But the executions and robberies of the population by the Cossacks in Tambov, Kozlov, Yelets, etc. only embittered the peasants. After such a visit, the peasants not only did not rebel against the Soviets, but on the contrary, they were burning with the desire to take revenge on the Whites. When Comrade Trotsky issued an appeal to the population, telling the peasants to gather themselves against the Whites, the peasants themselves began to form detachments against Mamontov.

In our units during the civil war, robberies and violence were strictly punished. Thus, during a raid by our 8th cavalry division, one of the commanders committed violence in one village. This unworthy act caused indignation among the peasants. Then the division commander, Comrade Primakov, held a meeting where he explained the inadmissibility of such an act and shot this commander in front of the peasants and troops. This calmed the population. The residents understood that the Reds would punish for such acts.

Every Red Army soldier on a raid must be an agitator, i.e. he must educate the peasants and workers of those villages and towns in which the detachment stops, the Red Army soldier must not rob or oppress the residents, but on the contrary, explain what Soviet power is, what it is fighting for. The residents will always understand the simple language of the same peasant, which the Red Army soldier is, and will become his friends.

Raids cause great harm to both troops and civilians. General Mamontov and the Cossacks destroyed not only Soviet government institutions, but the Cossacks mercilessly robbed and shot the civilian population. From this it is clear that raids must be fought not only by troops, but by the entire population. Usually, a cavalry detachment is sent out to pursue an enemy detachment that has penetrated into the rear. But it is almost impossible to detect the movement of enemy cavalry, and therefore it is very difficult to destroy it. Such cases are rare. The population itself, where the cavalry passes, can be of great help in the fight against raids. More than a hundred years ago, during the war of 1812 with the French, it is known how peasants, when the French appeared, drove their cattle into the forests and hid grain. The French army suffered a great shortage of food. Peasant volunteer detachments also caused a lot of harm to the French. Hiding in the forests, peasants, armed with guns, clubs, pitchforks, and others, attacked and destroyed them. Thus, the fight against raids depends largely on the population itself.

What should the workers and peasants of the Soviet Union do when they are attacked by enemy cavalry?

The answer to this was especially well stated by the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic during Mamontov’s raid in the following appeal.

“ON THE WAVE”

The White Guard cavalry has broken through to the rear of our troops and is bringing disorder, fear and devastation wherever it appears. The task of the White Guard cavalry is to frighten our southern troops pressing on Denikin and to force them to retreat. But this hope is in vain. The Red regiments on the southern front have maintained unshakable firmness and are successfully advancing in the most important areas. The front line confidently tells the Red fighters: continue your work: the rear will cope with the raid of Denikin’s bandits.

And this is now the sacred duty of the rear, especially in the Tambov province.

The task is clear and simple: to surround Denikin’s cavalry, which had broken away from its depots, with a strong raid and tighten the lasso with a confident hand.

For this it is necessary that the worker-peasant masses, under the leadership of their councils and communist organizations, rise to their feet as one man against the white raiders. It is necessary to make the landlords’ mercenaries feel that they have found themselves in a worker-peasant country, i.e., a country hostile to them.

Danger must lie in wait for white bandits from every corner, from behind every hill, from behind every ravine. When they approach, peasants must promptly steal horses, cattle, carts, take away grain and all kinds of food. What they do not manage to take away must be destroyed. Soviet power will cover all losses incurred. Woe to the peasant who voluntarily helps the landowner’s troops in any way.

Communists, to the front lines! In all villages, volosts, districts, cities of Tambov province and neighboring districts of other provinces, communist organizations must ask themselves the question: how and by what means can we now directly harm the raiders and make things easier for the regular units.

Reconnaissance must be carried out superbly. Information must be collected on every enemy patrol, followed, and, having taken them by surprise, destroyed or captured. Wherever the Whites decide to spend the night, they must be awakened by a fire. Their cavalry must run into barbed wire where the path had been clear the day before.

Woe to the executive committee that leaves its place without extreme necessity, without causing Denikin’s forces all the harm it is capable of.

A pack of Denikin’s predatory wolves has burst into the territory of the Tambov province, slaughtering not only peasant cattle, but also working people. To the raid, workers and peasants! With weapons and clubs. Do not give the predators any time or term, drive them out from all ends. At the whites! Death to the butchers!”

.

Autore: Popov V. I. (Попов В. И.)

Lascia un commento