REASONS FOR OUR REVERSES

The minor part played by the fleet—The small carrying capacity of the Siberian and Eastern Chinese Railways—Absence of any diplomatic arrangements to permit of the unhampered dispatch and distribution of our forces—Delay in mobilization of reinforcements—Disadvantages of “partial mobilization”—Transfer during the war of regulars from military districts in European Russia into the reserve—Delay in the arrival at the front of drafts—Weakening of the disciplinary powers of commanders as to the punishment awarded to private soldiers—Delay in promoting those who distinguished themselves on service—Technical shortcomings.

After a succession of great battles,[76] our army retired fighting on to the so-called Hsi-ping-kai positions in March, 1905, and remained there, increasing in strength, till the conclusion of peace. This peace, which was as unexpected as it was undesired by the troops, found them putting the finishing touches to their preparation for a forward movement. Later on, in its proper place, will be described the high state of readiness to which we had arrived in August 1905—a pitch of efficiency never before known in the history of the Russian army.

General Linievitch was awaiting the arrival of the 13th Army Corps—the last to be dispatched—before commencing decisive operations. The leading units of this corps had arrived at Harbin and its rear had passed through Cheliabinsk, and the army, now 1,000,000 strong, well organized, with war experience to its credit, and with established reputation, was making ready to continue the bloody struggle; while the enemy, so we learned from reliable reports, was beginning to weaken both in strength and spirit. The resources of Japan appeared to be exhausted. Amongst the prisoners we began to find old men and mere youths; more were taken than formerly, and they no longer showed the patriotic fanaticism so conspicuous among those captured in 1904. We, on the other hand, were able to free our ranks to a great extent of elderly reservists by sending them to the rear and to perform non-combatant duties; for we had received some 100,000 young soldiers, a great portion of whom had volunteered for the front. For the first time since the commencement of hostilities the army was up to its full strength. Some units—the 7th Siberian Corps, for instance—were over strength, so that companies could put more than 200 rifles into the firing-line after providing for all duties. We had received machine-guns, howitzer batteries, and a stock of field railway material which made it possible to transport to the army the supplies which had been collecting for some months. We possessed telegraphs, telephones, wire and cable, tools—everything. A wireless installation had been put up and was in working order; the transport units were up to strength, and the medical arrangements were magnificent. The force was in occupation of the strongly fortified Hsi-ping-kai positions, between which and the Sungari River there were two more fortified defensive lines—Kung-chu-ling and Kuang-cheng-tzu. There is little doubt that we could have repulsed any advance of the enemy, and, according to our calculations, could have assumed the offensive in superior force. Never in the whole of her military history has Russia put such a mighty army in the field as that formed by the concentration of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Manchurian Armies in August, 1905.

Such were the favorable conditions existing when we suddenly received the fatal news that an agreement had been come to with Japan at Portsmouth.

It is clear, therefore, that the war ended too soon for Russia, and before Japan had beaten the army which was opposed to her. After defending every yard, we had retired to Hsi-ping-kai, and were, after a year’s fighting, still in Southern Manchuria. The whole of Northern Manchuria, including Harbin and part of Southern Manchuria, with Kirin and Kuang-cheng-tzu, was still in our hands, and the enemy had nowhere touched Russian territory, except in Saghalien. Yet we laid down our arms, and besides ceding half the Island of Saghalien to the enemy, literally presented them—what was strategically far more important—with the Hsi-ping-kai and Kung-chu-ling defensive lines, together with the fertile districts which had fed our hosts, and it was with mixed feelings of shame and bewilderment that we withdrew in October, 1905, into winter quarters on the Sungari River. None of the many misfortunes which had befallen us had such an evil effect on our troops as this premature peace. Upon assuming command, I had assured the army that not a man would be allowed to return to Russia until we were victorious, that without victory we would all be ashamed to show our faces at home, and the men had really become imbued with the idea that the war must be continued till we won. This was even recognized by the reservists, many of whom said to me: “If we return home beaten, the women will laugh at us.” Such a sentiment is, of course, not as valuable as a wave of patriotism and a display of martial spirit before hostilities; but under the conditions in which this war had to be conducted, the mere acknowledgment by the whole army that without victory a return to Russia was impossible augured well for any future fighting. Such, then, being the conditions, the future historian must admit that, although unsuccessful in the first campaign, our land forces had grown in numbers, had gained experience, and had acquired such strength at last that victory was certain, and that peace was concluded before they had been really defeated. Our army was never fully tested; it had been able to concentrate but slowly, and, consequently, suffered in detail from the blows of a more ready enemy. When, after enormous sacrifices, it was eventually able to mass in strength and was furnished with everything requisite for a determined campaign, peace was concluded.

It cannot be truly said that the Japanese land forces had defeated ours. At Liao-yang, on the Sha Ho, and at Mukden, a comparatively small portion of our army was opposed to the whole armed might of Japan. Even in August and September 1905, when almost all our reinforcements had been collected in the Manchurian theatre of operations, we had only put about one-third of all our armed forces in the field. Our navy was almost entirely destroyed at Port Arthur and in the battle of Tsushima, but our army in the Far East was not only not destroyed, but had been gradually strengthened by the reinforcements received, and, after the battle of Mukden, by the expansion of the three-battalion East Siberian Rifle Regiments to four-battalion regiments, and the formation of the 10th East Siberian Rifle Division. These measures alone added seventy-six battalions of infantry to its strength. We must, therefore, look further afield than to our numerical strength for the causes of our disasters. Why was it that right up to March 1905, our troops were unable to win a battle? It is difficult to reply to this, because we do not yet know the strength of the enemy in the principal battles. We know approximately the numbers of battalions of the peace army which were in the field, but not the number of reserve battalions at the front, and, consequently, the actual number of rifles. In war the issue is not decided by the number of men present, but by the number of rifles actually brought into the firing-line.

It is quite possible that when a trustworthy history of the war compiled from Japanese sources is published, our self-esteem will receive a severe blow. We already know that in many instances we were in superior strength to the enemy and yet were unable to defeat them. The explanation of this phenomenon is simple. Though they were weaker materially than we were, the Japanese were morally stronger, and the teaching of all history shows that it is the moral factor which really counts in the long run. There are exceptions, of course, as when the side whose moral is the weaker can place an absolutely overwhelming force in the field, and so wear out its opponents. This was the case of the Federals as compared with the Confederates in America, and of the British against the Boers. It is indeed a lucky army which, starting a campaign with the weakest moral, is able to improve in both spirit and numbers at the same time.

This was the case with us. Between the battle of Mukden and the end of the war our army almost doubled in numbers, had taken up a strong position, and was quite ready to advance. The strength of the Japanese, on the other hand, was exhausted (they were reduced to filling up their ranks with their 1906 recruits), and many things pointed to a weakening of their spirit. As Japan was pre-eminently a naval Power, our principal operations should have been on the sea; and had we destroyed the enemy’s fleet, there would have been no fighting on Chinese territory. As I have already pointed out, our fleet scarcely assisted the army at all; for while taking shelter in Port Arthur, it did not attempt to prevent the enemy’s disembarkation. Three Japanese armies—those of Oku, Nodzu, and Nogi—landed unhindered on the Liao-tung Peninsula; the forces of Oku and Nogi actually landed close to where our squadron was lying. Though we possessed an excellent base at Vladivostok, our main fleet was collected at Port Arthur—in a naval sense a very inferior place, for it possessed no docks nor workshops, and no protection for the inner basin.

As regards our naval strength, I am unable to refer to official figures, for I write from the country,[77] but I quote from an article published in the Ruski Viestnik in 1905 by M. Burun, as much of what he says agrees with what I had previously known. Our fleet began to increase after the Chino-Japanese War, the naval estimates reaching £11,200,000 in 1904. At the outbreak of hostilities it consisted of 28 sea-going and 14 coast-defence battleships, 15 sea-going gunboats, 39 cruisers, 9 ocean-going destroyers, 133 smaller destroyers, and 132 auxiliary vessels of less importance. Between 1881 and 1904 we had spent £130,000,000 in the creation of this fleet. The naval estimates of the two nations for the years preceding the war were, in millions of pounds:

| 1899. | 1900. | 1901. | 1902. | 1903. | |

| Russia | 9 | 9⋅6 | 10⋅8 | 11⋅2 | 12⋅0 |

| Japan | 6 | 4⋅5 | 4⋅1 | 3⋅2 | 3⋅2 |

The Japanese fleet consisted of:

| Sea-going battleships | 6 |

| Coast-defence battleships | 2 |

| Armoured cruisers | 11 |

| Unarmoured cruisers | 14 |

| Destroyers | 50 |

| Gunboats | 17 |

At the commencement of war our Pacific Ocean Squadron consisted of:

| Sea-going battleships | 7 |

| Large cruisers (4 were armoured) | 9 |

| Small cruisers and minor ships | 4 |

| Destroyers | 42 |

Our fleet was neither ready nor concentrated. Four cruisers were at Vladivostok, one at Chemulpo, and the greater part of the Port Arthur Squadron lay in the inner roads. A few days before the attack of February 9 it moved out into the outer roads to carry out steam trials, but proper precautions were not observed, even though diplomatic relations had already been broken off.

As far back as 1901 our Headquarter Staff had estimated that in the event of war our Pacific Ocean Fleet would be weaker than Japan’s, but within two years of that date Admiral Alexeieff, the Viceroy, stated in the scheme for the strategical distribution of our troops in the Far East[78] that the defeat of our fleet was impossible under existing conditions.

In their night attack of February 9 the Japanese put several of our best ships out of action; but, serious as the damage was, it could have been speedily repaired had we possessed proper facilities in Port Arthur. Though we had expended many millions in constructing docks and quays at Dalny, Port Arthur was without a dock, and repairs could only be executed slowly. Still, our Pacific Ocean Squadron revived when Admiral Makharoff arrived, and for a short time its chances of success were much increased. After Makharoff’s death the command passed to Admiral Witgeft, who, upon receiving instructions to force his way through to Vladivostok, put to sea and engaged Togo’s squadron. Witgeft was killed, and the fleet inflicted some damage on Togo’s squadron, and returned to Port Arthur without the loss of a single ship. The battle of August 10 was indecisive, though our blue-jackets fought gallantly the whole day against a numerically superior enemy, and beat off numerous attacks by destroyers. After returning to Port Arthur the fleet finally assumed its passive role, and was gradually disarmed—as in the Siege of Sevastopol—in order to strengthen the land defense of the fortress, where our sailors did most excellent work. What it might have accomplished on its own element can be gauged from the performances of the gallant little cruiser squadron under Admiral Essen, which made a daring sally from Vladivostok to the coasts of Japan. Not only did Essen’s success cause considerable consternation in Japan, but it resulted in action of practical value to the army, for one vessel sunk by the squadron was conveying siege material for use against Port Arthur. On October 14, 1904, Admiral Rozhdestvenski’s fleet, consisting of 7 battleships, 5 first-class cruisers, 3 second-class cruisers, and 12 destroyers, with a complement of 519 officers and 7,900 men, left Libau for the Pacific Ocean, and Admiral Nebogatoff’s squadron left to join it on February 16, 1905. The latter consisted of 1 sea-going battleship, 3 coast-defence battleships, and 1 first-class cruiser, with a complement of 120 officers and more than 2,100 men. Rozhdestvenski’s squadron had to steam 16,400 miles to reach Vladivostok. In spite of the lack of coaling stations en route, and in the face of extraordinary difficulties, it eventually succeeded in reaching the Sea of Japan, where it was utterly destroyed on May 27 and 28, 1905, off Tsushima. In twenty-four hours we lost 30 pennants sunk or captured out of 47, and 137,000 from a total tonnage of 157,000. The light cruiser Almaz and 2 destroyers—the Grozni and Bravi—alone reached Vladivostok. According to Admiral Togo’s reports, he lost only 3 destroyers, while his casualties amounted to 7 officers and 108 men killed, 40 officers and 620 men wounded. Many gallant exploits were performed by our sailors in the fight: the battleship Suvaroff continued firing until she sank, and of the Navarin’s complement only two men were saved; while the small ironclad Ushakoff replied to the Japanese summons to surrender with a broadside, and foundered with the whole of her crew. M. Burun closes his remarkable article in the following words:

“Undoubtedly many tactical mistakes were among the contributory causes of the Tsushima catastrophe: our initial error in allowing transports to be with the fleet, the unseaworthiness and the conspicuous colour of our ships, and many such details; but the real cause was the unreadiness of our fleet for war, and the criminal short-sightedness of our Administration. Such a contingency as war was never contemplated, and the fleet was kept up entirely for show.

“Our crews were of the best material in the world; they were brave and capable of learning, but besides being unversed in the use of modern implements of war (such as automatic gun-sights, etc.), they were not accustomed to life at sea. Our officers were possessed of a strong sense of duty, and thoroughly appreciated the immense importance of the task before them; but they were new to the crews and to the ships, which they had suddenly to command against a fleet trained in the stern school of war. Born sailors, the Japanese seamen never left their ships, while our vessels had neither permanent nor full crews. Even in the last eight months of the cruise of our fleet our captains were unable, owing to the shortage of ammunition, to put their crews through a course of gunnery, or to test their training. The ships only carried enough ammunition for one battle. Yes, we lost our fleet because the most important element—the personnel—was unprepared. We lost the war, and lost our predominance on the Pacific Ocean, because, even while preparing to celebrate the anniversary of the gallant defence of Sevastopol, we quite forgot that the strength of a navy is only created by the spirit of every individual member belonging to it.

“But can it be that there is no one left of all those gallant sailors who so proudly sailed under the Cross of St. Andrew who possesses the secret of training men? If so, then our Navy Department will never succeed in creating a fleet. However many the milliards spent, it will only succeed in constructing a collection of ships such as now rest at the bottom of the Sea of Japan. Mere ships do not make a fleet, nor do they form the strong right arm of an empire, for the strength of a nation does not lie in armour, guns, or torpedoes, but in the souls of the men behind these things.”

Far from assisting our army, Rozhdestvenski brought it irreparable harm. It was the defeat of his squadron at Tsushima that brought about negotiations and peace at a time when our army was ready to advance—a million strong. As at Sevastopol in 1855, the only assistance given by our fleet to Port Arthur, except at Chin-chou, was to land blue-jackets and guns.

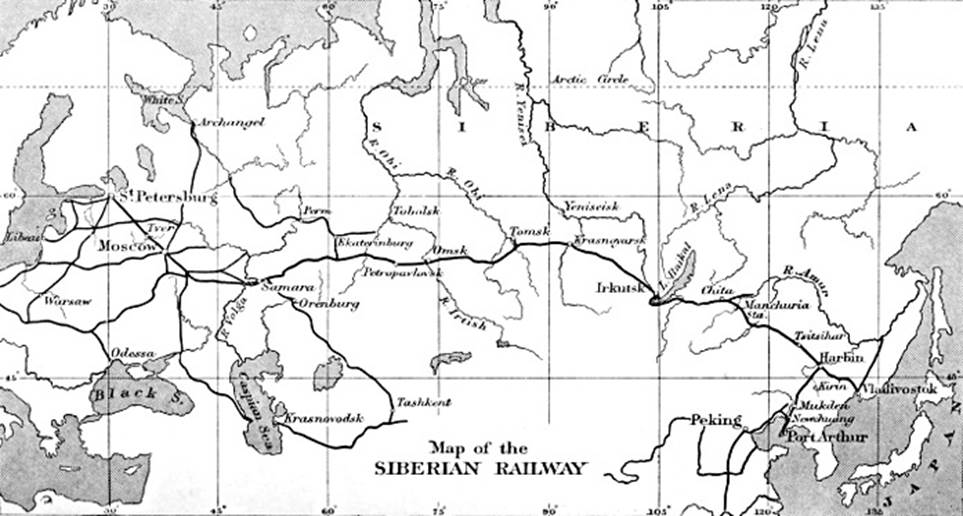

Next to the absence of a Russian fleet, the most important factor to assist the Japanese in their offensive strategy and to impede us was the condition of the Siberian and Eastern Chinese Railways. If these lines had been more efficient, we could have brought up our troops more rapidly, and, as things turned out, 150,000 men concentrated at first would have been of far more value to us than the 300,000 who were gradually assembled during nine months, only to be sacrificed in detail. In my report upon the War Ministry in 1900 (before Japan had completed her armaments), I wrote that she could mobilize 380,000 men and 1,090 guns, about half of which could be transported across the sea; that there were immediately ready only seven divisions, with a war strength of 126,000 rifles, 5,000 sabers, and 494 guns. In March, 1903, before visiting Japan, I calculated that if the views then held by our naval authorities as to the comparative strength of the two fleets were correct, we ought to be ready, in the event of war, to throw an army of 300,000 into Manchuria. In the battles of Liao-yang and the Sha Ho we only had from 150,000 to 180,000. If we had had a better railway, and had been able to mass at Liao-yang the number specified, we should undoubtedly have won the day, in spite of our mistakes.

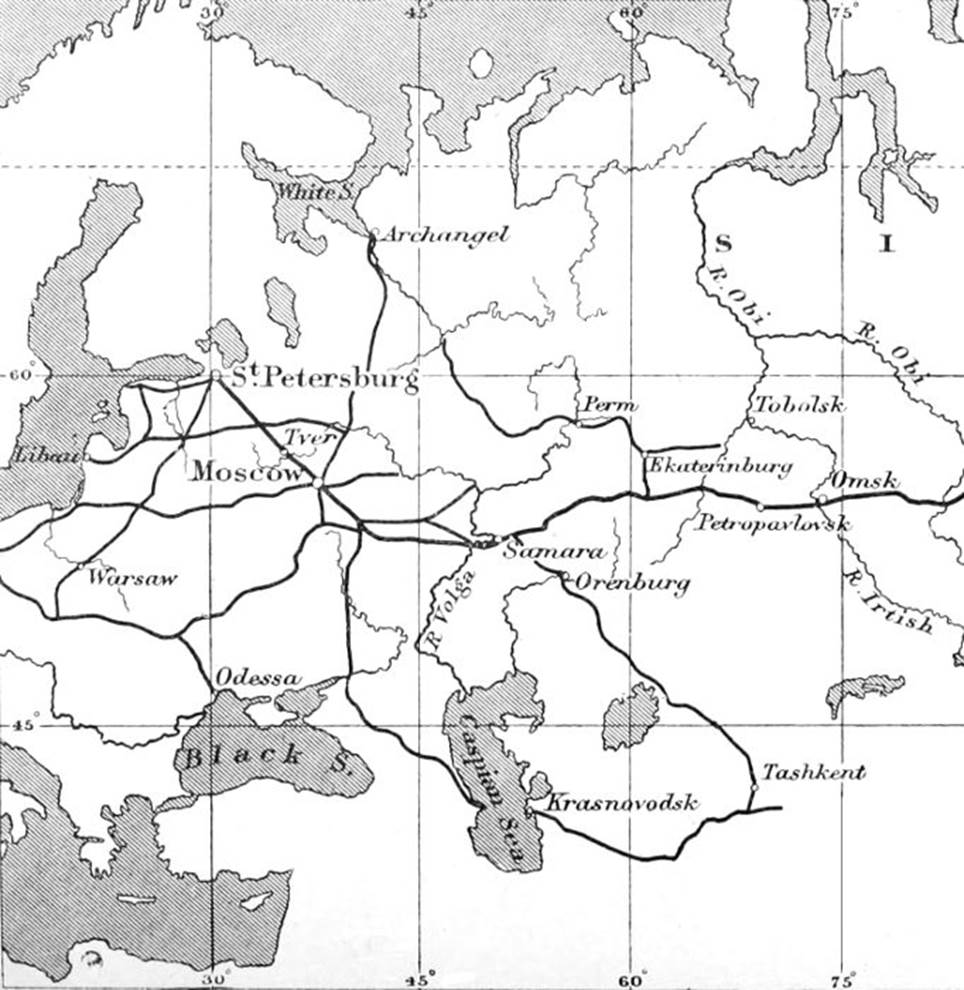

Map of the siberian railway.

The siberian railway: western line.

The siberian railway: eastern line.

As regards the railway problem, we counted, in August, 1901, on having for military transport purposes on the Eastern Chinese Railway 20 wagons running in the twenty-four hours, while in the summer of 1903 we calculated we should have 75. We were promised from January 1, 1904, five pairs[79] of military trains of 35 wagons each, or 175 wagons each way; and it was supposed at the same time that the Siberian Railway would be in a condition to run seven pairs of military trains in the twenty-four hours, but these hopes were not realized. Let us see what actually did happen.

In 1903 we were only able to reckon on four through military trains on the Siberian line, and on three short trains on the Eastern Chinese. Towards the end of that year relations with Japan became strained; it seemed as if, having made all her preparations, she was seeking a pretext for war, and was therefore meeting all the concessions we made by fresh and quite impossible demands. Our unreadiness was only too plain, but it seemed at that time that we should be able, with two or three years’ steady work, so to strengthen our position in the Far East and improve the railway, the fleet, the land forces, and the fortresses of Port Arthur and Vladivostok, that Japan would have small chance of success against us. It was proposed, in the event of trouble, to send out, to begin with [in addition to the troops already in the Far East], reinforcements consisting of four army corps (two regular and two reserve) from European Russia. Owing to the unreadiness of the railways, and the uncertainty as to the time it would take to improve them, it was impossible to draw up concentration time-tables with any accuracy. According to these tables, 500 troop trains and a large number of goods trains would be necessary to transport from European Russia the drafts for the Far East, the 3rd Battalions of the East Siberian Rifle Regiments, several batteries, local units and ammunition parks for the East Siberian Rifle Divisions, the 4th Siberian Corps, and the two army corps from Russia (10th and 17th). Moreover, upon mobilization, the Siberian Military District would require local transport for a very considerable distance. This would add about three weeks to the time required for through transport of the above reinforcements.

As I have said, we expected that from January 1904, the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines would be able to give us daily five trains each way; but the concentration of one-half of the reinforcements to go to the Far East actually took five months from the declaration of war. One of the most important of the War Minister’s tasks, therefore, was to get the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines into a more efficient state as rapidly as possible. My scheme was to improve them at first up to a capacity of seven trains each way in the twenty-four hours, and on the southern branch of the Eastern Chinese (along which movements would have to take place through Harbin from both sides, from Pri-Amur and Trans-Baikal) to fourteen pairs of trains. My proposal was approved by the Tsar, who noted against the figure fourteen the words, “Or even up to twelve pairs of military trains.” In the middle of January, 1904, he appointed a special committee to consider the questions of the money and time required for the immediate improvement of the railways as suggested. This committee, consisting of the Ministers of War, Ways and Communications, Finance, and the State Comptroller, was under the presidency of General Petroff, of the Engineers. It was instructed to ascertain what should be done to enable seven pairs of military trains to be run on the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines, and twelve pairs on the southern branch (from Harbin to Port Arthur).

On January 29, 1904, the Viceroy wrote of the state of the Eastern Chinese Railway as follows:

“According to my information, there is reason to doubt the official figures as to the carrying capacity and the ability to cope with increased traffic of the Eastern Chinese Railway. Rolling-stock is deficient, and many engines are out of order. The water-supply is so uncertain that the officials have recently been forced to refuse to accept goods for transport. The soldiers are the only reliable portion of the subordinate railway staff, and on this account some alarm is already felt by the higher officials. But the most serious want is that of a sufficient fuel reserve. The bulk of the coal is stocked at Dalny, whence 1,000 tons have to be distributed over the line daily, of which amount only half goes to increasing the reserve, the other half being required for current consumption. To transport the whole of the reserve by rail from Dalny would take about twenty-five days, but the railway would even then be able to cope with the increased traffic for a period of three months only. In war we can scarcely count on the large railway demands being met, as the coal is sea-borne.”

An official statement, prepared to show the then position of the railway, was laid before the special committee at a sitting held four days before the commencement of hostilities. According to the Minister of Ways and Communications (Prince Khilkoff), the Siberian line could only run six pairs of through trains, of which four were military, one was passenger, and one service (for the railway); owing to the scarcity of rolling-stock, only three of the four military trains could carry troops, the fourth being given up to goods (trucks). But the War Department representative in charge of Transport, who was at the meeting, pointed out that on the portion of the Trans-Baikal line, between Karim and Manchuria station, only three trains altogether, whether of troops or goods, could be run. The official information furnished by the Ministry of Ways and Communications thus differed from that of the military railway representative. The representative of the Eastern Chinese Railway stated that it would soon be possible to run a total of five pairs of trains on that line, while he calculated on working up by April to a running capacity of six pairs along the main line and seven pairs on the southern branch. On going into details as to the work that would be necessary before this could be done, it was discovered that, owing to the very inferior equipment of the different branches of the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines, the necessary additions to rolling-stock and the construction of sidings, crossings, and water-supply would absorb a very large sum. The workshops on the Eastern Chinese line were poorly equipped, and there were not nearly enough engine depots, while the large amount of rails, fish-plates, sleepers and ballast necessary would have to be conveyed while the transport of troops was going on. On March 9 I wrote to General Sakharoff, then in charge of the War Department, and pointed out that, owing to what I had heard as to the deficiency of engine depot in the Viceroyalty, and in order to facilitate concentration, I considered it essential that, up to Manchuria station, not more than one train a day should be taken up for goods, the remainder being reserved for troops.

Lake Baikal was the great obstacle on the Siberian Railway. The ice-breaker did not work regularly, and progress on the construction of the Circum-Baikal line was slow. Prince Khilkoff conceived and carried out the idea of laying a temporary line across the ice of the lake, and so passing the wagons over. He also proposed to dismantle the locomotives, take the parts across by horse traction, and reassemble them on the eastern side. On February 16 I received the following letter from him:

“I have returned from inspecting the Trans-Baikal line. The line will be able immediately to run six pairs of trains of all kinds. I have started work building sidings for nine pairs, but this number will not run until the warm weather sets in and we get rolling-stock. Almost all the rivers now are frozen solid. Thirteen temporary water-supplies are now under construction. I will write again about the warm weather and the increase up to twelve pairs of trains. Khorvat, whom I saw in Manchuria, tells me that the following numbers of military trains can be run on that line[80]: three pairs on the western portion, five on the southern. The further traffic acceleration depends almost exclusively on the receipt of rolling-stock. Heavy snowstorms have somewhat delayed the laying of the line across Lake Baikal; but I have hopes of success. Arrangements are being made at Manchuria station for the temporary accommodation of 4,000 to 6,000 men in hut barracks.”

It is clear from this letter that when we entered upon hostilities we had for mobilization, concentration, and the carriage of supplies only three military trains in the twenty-four hours, for the carrying power of the western branch of the Eastern Chinese line from Manchuria station to Harbin fixed the capacity of the line throughout its whole length from Europe to Harbin. Thus, in the first period of the war, Lake Baikal was not the only obstacle to rapid transit. The freezing of the rivers in Trans-Baikalia was also a serious difficulty, and necessitated the improvisation of water-supply at numerous stations. But what was most wanted was an early delivery of rolling-stock for the Trans-Baikal and Eastern Chinese lines, where the running capacity was considerable, but the carrying capacity was limited—owing to the shortage of rolling-stock—to three military trains in the twenty-four hours. Under normal conditions we should have been compelled to wait for the opening of Lake Baikal in the spring before commencing the transport of rolling-stock eastwards from it, which would have meant that we should have had to be content with three pairs of trains till the middle of March. The ability and immense energy of Prince Khilkoff, however, rescued us from this serious plight. Though in very bad health, he took the matter in hand personally, regardless of the climate and all other difficulties. On March 6 I received the following message from him:

“On the 17th [February] we began to send rolling-stock across the ice [Lake Baikal]. More than 150 wagons have been sent across, and about 100 are now on their way over. If the weather is favorable, I shall start sending engines over.”

On March 9 I received another message, recounting the difficulties that were caused by the frequent great changes of temperature, for the ice on the lake cracked badly, and it was often necessary to relay the line just put down. He asked me to help him with fatigue-parties from the army, which I gave him.

What had to be done in order to improve, to some extent, the Manchurian line, is recorded in the report of the special committee submitted to me on March 9, 1904. The officials of the Eastern Chinese Railway calculated that to increase the carrying capacity of its main line up to seven, and of the southern branch to twelve, pairs of military trains, would entail an expenditure of £4,424,000. With this sum the following improvements in actual traffic might be made: On the main line, up to 7 pairs of troop trains, 1 pair of passenger, 1 pair service; total, 9 pairs; running capacity, 10 pairs; water-supply for 10 pairs. On the southern line, up to 12 pairs troop trains, 1 passenger train, and 2 service; total, 15; running capacity, 16; water-supply for 16. Among the chief items were the laying of eighty odd miles of sidings, which necessitated the delivery and distribution along the line of between 9,000 and 10,000 tons of rails, sleepers, and fish-plates, and the construction of 224 engine-sheds, 373,400 square feet of workshops, and 265,600 square feet of platforms. For the construction of dwelling-houses £400,000 was necessary. The water-supply of the southern branch was to be increased by 60 per cent., and rolling-stock, of the value of £2,300,000, including 335 engines, 2,350 covered wagons, 810 trucks, and 113 passenger coaches, were to be supplied. This increase in traffic to seven pairs of military trains on the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines and twelve on the southern branch was, of course, only a first instalment of what was required. Orders were issued in June, 1904, when I was in Manchuria, for the respective lines to be brought up to the above capacity.

Before my departure to take over command of the army in the Far East, I submitted a statement to the Tsar on March 7, showing what was most urgently required to enable us to fight Japan successfully. This was endorsed by the Tsar himself, and sent to the War Minister, General Sakharoff. The following is an extract from it:

“I have the honor to report that the following are the measures which, in my opinion, are most urgently required:

1. Improvement of the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines so as gradually to work up to fourteen pairs of military trains in the twenty-four hours over the whole length, and eighteen pairs on the southern branch. Every additional pair of trains will not only shorten the time for concentration, but will at the same time help the supply services. Great difficulties will be encountered in carrying out what I recommend, especially in increasing the running capacity on the Central Siberian and Trans-Baikal lines. Once these difficulties are overcome, the necessary increase of traffic can easily be attained by means of a loan of rolling-stock from other lines. I venture to assert that of all urgently pressing questions, that of improving the railway communication between Russia and Siberia is the most important. It must therefore be taken up at once in spite of the enormous cost. The money expended will not be wasted; it will, on the contrary, be in the highest sense productive, inasmuch as it will shorten the duration of the war.

2. … Together with the carriage of troops and goods by rail, a transport service must be organized on the old Siberian road and on that alongside the Eastern Chinese Railway. For a successful concentration and the rapid transit of supplies, we ought to have thirty troop trains in the twenty-four hours. Even when the measures I suggest are carried out, we shall only have a total of fourteen pairs—less than half of what are really required. Our present precarious position, therefore, can be realized, as the total number of military trains we are able to count upon between Baikal and Harbin is four pairs!”

When I travelled over the Siberian and Manchurian lines in March, 1904, I was accompanied by M. Pavlovski, who was in charge of the Siberian line. He told me that if he were given rolling-stock on loan, he would be able that year to increase the number of military trains to ten, and later on to fourteen, pairs, at a cost of £650,000. On receiving his report, I sent on March 19 the following message to General Sakharoff:

“With this I am telegraphing to Secret Councillor Miasiedoff Ivanoff as follows:

“ ‘I earnestly request you to arrange for the early improvement of the running and carrying capacity of the Siberian Railway. Engineer Pavlovski, in charge of the Siberian line, informs me that he has already represented that, in order to work up the number of trains on the western portion to thirteen, in the central to fourteen, and in the hilly portion fifteen (of which nine, ten, and eleven will be military) during the summer, an expenditure of £650,000 is absolutely necessary. Please arrange as soon as possible to credit him with this amount and an equal sum for the Trans-Baikal line. I have informed the Tsar as to my opinion of the necessity of eventually working up the whole line from the Volga to Harbin to fourteen trains, though it be only twelve at first. Pavlovski considers it desirable and possible to get seventeen pairs of through trains. I cannot hope to act energetically unless the railway to Harbin is improved to the extent I recommend. From Harbin onwards it is absolutely necessary eventually to have eighteen, and temporarily fourteen, pairs of trains. I earnestly beg you to support this request.’ ”

By the middle of March Prince Khilkoff succeeded in sending across the ice-line on Lake Baikal sixty-five dismantled locomotives and 1,600 wagons. [When I met him he was very ill, but had succeeded in accomplishing a tremendous work, which it is to be hoped the country will appreciate.] Echelons[81] of troops marched twenty-nine miles over the ice in the day, every four men having a small sledge to carry their kit, etc. When I passed across the lake not more than four echelons were crossing in the twenty-four hours. The Trans-Baikal line was working very badly, and together with the lake was a great cause of delay.

In order to expedite the troop moves in Southern Manchuria, I telegraphed to the Viceroy on March 16, emphasizing the necessity of improvising road transport on the many roads between Harbin and Mukden for the carriage of units and supplies from the former place, and of not taking up more than one train in the day on the southern branch for goods. At the same time I drew attention to the fact that the troops should not be allowed to take with them more than their field-service scale of baggage. I had noticed that the 3rd Battalion of the East Siberian Rifles, which I had inspected on the way to the front, were taking as much baggage as if moving in the course of ordinary relief. On March 27 I reached Liao-yang, where the weary wait for the arrival of reinforcements began. The first troops to arrive were the 3rd Battalions for the seven East Siberian Rifle Brigades, at first one and then two in the day. These were followed by the artillery units and drafts for the brigades of the 31st and 35th Divisions. Meanwhile the money required for the improvement of the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines had not been allotted as quickly as it should have been. On May 19 I received from the Ministry of Finance a telegram forwarding a copy of another to the Viceroy, dated 15th. From this it appeared that the question of bringing the carrying capacity of the Eastern Chinese Railway up to seven pairs of trains, and that of the southern branch to twelve pairs, had been thoroughly gone into at numerous meetings of the special committee, and that the necessity for dispatching the following to the line was recognized: 190 miles of rails with joints, 770 sets of crossings, 355 engines, 88 passenger coaches, 2,755 goods vans and trucks. In addition to these, Admiral Alexeieff asked for 30 miles of rails, 265 sets of crossings, and 1,628 vans. The Finance Minister stated that it would be necessary, in order to improve and develop the line, to provide it with 3,000 truck-loads of various stores. But as it had only been found possible to send 200 trucks in April and 201 in May, or a total of 401, he was of opinion that “the whole amount could not possibly be guaranteed earlier than the autumn.” The extent to which the despatch of these was delayed is evident from the fact that out of 1,000 vans, only 60 had been sent off by May 18, and out of 355 engines, only 105. By July 30, 120 more engines had been sent, but it was not proposed to forward the remaining 130 till a good deal later.

Owing to three regiments of the 1st Siberian Division being detained in Harbin during the whole of April, the Manchurian army was not augmented by a single battalion. Meanwhile we had been defeated on May 1 at the Ya-lu, and on the 6th Oku’s army had begun to disembark at Pi-tzu-wo.

Though the 2nd Siberian Division reached Liao-yang in the second half of May, we were still very weak. On May 23 General Jilinski brought me a letter from the Viceroy, in which Admiral Alexeieff wrote that the time had come for the Manchurian army to advance towards the Ya-lu or Port Arthur. In spite of my opinion as to our unreadiness for any forward movement, in spite of the fact that out of twelve divisions of reinforcements only one had arrived, in spite of the inefficiency of the railway, an advance with insufficient numbers was ordered and carried out. The result was the disaster on June 14 at Te-li-ssu. The leading units of the 10th Corps did not reach Liao-yang till June 17; thus it took more than three months from the beginning of hostilities for our troops in the Far East to receive reinforcements from European Russia. During this prolonged and particularly important period the burden and heat of the campaign was borne by five East Siberian Rifle Divisions, whose two-battalion regiments had been expanded into three-battalion regiments as late as March and April; the 4th Siberian Corps, which arrived in May, did not take part in any fighting. Taking advantage of our inferiority in numbers, and especially the inaction of our fleet during these three months, the enemy disembarked their three armies on the Liao-tung Peninsula and in Kuan-tung. The 1st Army, under Kuroki, moved from Korea into Southern Manchuria, and Japan won three battles on land—at the Ya-lu, Chin-chou, and at Te-li-ssu. Had the railway only been ready at the beginning of hostilities, even to run only six through military trains, we should have had three army corps at Te-li-ssu—namely, the 1st and 4th Siberians and the 10th Army Corps, instead of only the 1st Siberian Corps. The issue of this battle would have been different, and this would undoubtedly have affected the whole course of the campaign, for we should have secured the initiative.

The arrival of the first units of the 10th Army Corps was more than opportune, but events did not permit us to await the concentration of the whole of it. Kuroki’s army was advancing, and the line Sai-ma-chi, An-ping, Liao-yang, on which he was moving in force, was only covered by our cavalry and one regiment of infantry. Consequently, as soon as the leading brigade of the 9th Division arrived at Liao-yang, it was sent off in that direction. Similarly, troops of the 17th Army and 5th Siberian Corps went straight into action from the train without waiting the concentration of their corps. It was only on September 2—i.e., after seven months—that the three army corps (10th, 17th, and 5th Siberian), sent from Europe to reinforce the field army, were all concentrated in the Manchurian theatre. During the decisive fighting at Liao-yang, the 85th Regiment was the only unit of the 1st Army Corps which had arrived, and it went straight from the train into the battle. If, at the beginning of the war, we had had only one more military train a day, we would have had present at the battle of Liao-yang the 1st Army Corps and 6th Siberian Corps, and with these sixty extra battalions must certainly have defeated the enemy. But the railway fatally affected us in other ways, for while we were feeding our army with fresh units as reinforcements, we were unable at the same time to find carriage for the drafts for the advanced troops, which had suffered heavy losses in killed, wounded, and sick. For example, in the fighting of five long months, from May 14 to October 14, the Manchurian army lost in killed, wounded, and sick, over 100,000 men, to replace which, during that period, it only received 21,000. The enemy, on the other hand, were making good their casualties quickly and uninterruptedly.

By the beginning of October the 1st Army Corps and the 6th Siberian Corps had arrived. Taking advantage of these reinforcements, I ordered an advance. In the bloody battle on the Sha Ho, where we lost about 45,000 men, killed and wounded, neither side could claim a decisive victory. During the four months immediately preceding the February (1905) battles the army received drafts to replace wastage, and was reinforced by the 8th and 16th Corps, besides five brigades of Rifles, but in that month it was still short of its establishment by 50,000 men—i.e., two whole army corps. In other words, as regards numbers, the 8th and 16th Corps might be said merely to have made up the wastage in the others. It is true these corps brought us additional artillery; but looking at it purely from the point of view of their fighting value, I should have preferred to have received them in the shape of drafts; I could then have incorporated them in the battle-tried corps, instead of having them as separate inexperienced units. Even with these considerable reinforcements our position in February, 1905, was worse than before, for the fall of Port Arthur enabled the Japanese to be augmented by Nogi’s army. Immediately after the 16th Corps the field army was to have received two Rifle brigades, one Cossack infantry brigade, and the 4th Army Corps; but their despatch was delayed for more than a month, in order to allow a quantity of stores which had collected on the line to be railed up. It was only on March 5—i.e., five weeks after the arrival of the last units of the 16th Army Corps—that the leading battalions of the 3rd Rifle Brigade (the 9th and 10th Regiments) reached Mukden, and they at once went into action. But for this break we should have had at the battle of Mukden a main reserve of more than sixty battalions, which, even allowing for our mistakes, might have turned the balance in our favor. In a full year, from the beginning of March, 1904, till the beginning of March, 1905, we railed up eight army corps, three Rifle brigades, and one reserve division to the front. Thus each corps on the average required, roughly, one and a half months to perform the journey. These figures indicate the peculiar disabilities under which we laboured in massing superior numbers. Owing to our far too slow concentration, our forces were bound to be destroyed in detail, as we were obliged to accept battle. With the transit of troops, the materials necessary for the work of improving the railways had to be railed up, and from August onwards the progress made in this work was remarkable. In October, 1904, I received a message from General Sakharoff to the effect that, according to the Minister of Ways and Communications, the Siberian main line would have a carrying capacity, after October 28, of twelve pairs of military trains. But this promise was not carried out for almost a year, though the traffic in October and November was heavy. Altogether, in one and a half months (forty-seven days), from October 28 to December 14, there arrived in Harbin 257 military, 147 goods (commissariat, artillery, red cross, and railway service), and 23 hospital trains (total, 427), which gives an average of nine pairs in the twenty-four hours, of which only five and a half carried troops. In ten months of war the railway had increased its traffic from three military trains to nine, so it took on an average more than one and a half months to add one pair of trains to the traffic. Finally, in the summer of 1905, after sixteen months of war, the railways worked, I believe, up to a rate of twelve pairs of military trains on the main line and eighteen on the southern branch—i.e., on the main line we did not even then get so high as the number (fourteen pairs) which I had asked for on March 7, 1904, when leaving for the front.

From all I have said it must be amply clear what a decisive factor the railway was. Every extra daily train would have enabled us to have at our disposal one or two corps more in the decisive battles. Thus a very great responsibility—that of not losing a single day in improving the lines—lay with the Ministries of Ways and Communications, of Finance, and, to a certain extent, with the Ministry of War. Looking back to what was done by these departments, it must be confessed that the results attained were very great, and that the railway employés did magnificent service. By the end of the war we had within the limits of the Viceroyalty an army of 1,000,000 men, well supplied with everything necessary for existence and for fighting. As this army was conveyed while work was being simultaneously carried out on the railway-line, the result, though largely attained by forced labour, was, for a badly laid single line of railway, somewhat striking. By means of good lines of railway, mobilization and concentration are very quickly effected nowadays. Germany and Austria can throw about 2,000,000 soldiers on to our frontiers in from ten to fourteen days, and their rapid concentration will enable them to seize the initiative. Our forces reached the front, so to speak, by driblets, which resulted in paralysis of all initiative on our part.

Thinking that the information with regard to the railways, sent by the War Minister in October, 1904 [which reached me on November 8], meant the realization of my recommendations of February, 1904, I considered it time to submit to the Tsar my views as to the necessity for further work, for I considered it most necessary that the line should be at once doubled over its whole length. I expressed my opinion on this question in a letter to the Tsar, dated November 12, 1904. As there is nothing in this letter that can be regarded as secret, I will quote it literally:

“YOUR MAJESTY,

“Before leaving to join the army, I was permitted to give my opinion as to our principal requirements to insure success in the war. My opinion was submitted in a memorandum dated 7th March, and was marginally annotated by Your Majesty. Eight months ago I expressed in this memorandum the opinion that, for a successful concentration and rapid transport of all the supplies necessary to an army in the field, the running of 30 pairs of military trains in the 24 hours was essential. As a first step I considered the improvement of the Siberian and Eastern Chinese lines should be taken in hand, so as to bring up the number of trains to 14 pairs in the 24 hours along the main line, and 18 pairs along the southern branch. Against the words ‘up to 14 pairs in 24 hours’ Your Majesty was pleased to note, ‘Very necessary.’ In a message reaching me on the 8th November the War Minister has informed me that from the 28th October the Siberian and Trans-Baikal lines will have a carrying capacity of 12 pairs of trains in the day, and that it is proposed further to work up the Siberian main line to 14 pairs, and that the Minister of Finance[82] has been approached with regard to the urgency for improving the Eastern Chinese lines so as to correspond with the Siberian. Thus, we have not, in eight months, reached the number indicated as necessary in my former memorandum. I now earnestly request that as a first step the whole Siberian main line and the Eastern Chinese line as far as Harbin should be worked up to a carrying capacity of 14 pairs, and on the southern branch to 18 pairs. I know that this is no easy matter, but it is absolutely essential and admits of no delay. These 14 pairs will by no means supply all our requirements. The larger number of men in the field has increased the demand for transport. It is calculated that, to supply the army with everything necessary, and to carry back what is not required, not 30 pairs of trains, but 48, are essential. This is not exaggerated; it is the minimum under normal conditions. Each Manchurian army should have its own line (like the Bologoe-Siedlce)[83] giving 48 pairs of trains in 24 hours. We must bow, of course, to the impossible, but we shall have to pay in human life and in money for a prolonged war. The urgency of every extra train can easily be seen. If we had had one more pair of trains available at the beginning of the war, we should have had 2 extra army corps—the 1st and 6th Siberian Corps—in the August fights at Liao-yang, and our success would practically have been assured. This one extra train could have brought in drafts during September and October an extra 50,000 men, of which we are now in such urgent need.

“In the future, every month will increase the necessity of strengthening the line still more. When the field army was small, we drew our supplies almost entirely from local sources (wheat, barley, hay, straw, fuel, and cattle), but these will soon be exhausted, and the provisioning the army will depend on supplies from Europe. When we move forward our position will become worse, for we shall be moving into a part of Manchuria already devastated by war, and into a hilly tract which was never rich in supplies. The daily transport of provisions (flour, groats, oats, hay, and meat) for our present establishment takes up 5 trains, and we soon shall have to provide carriage for live-stock. But the army cannot live from hand to mouth. A quantity of supplies must be collected, sufficient to form a reserve for the force for some months, besides satisfying current requirements, and this must be distributed in the advance and main depôts. It will take 5 additional trains a day for one month to collect one month’s reserve. Only by having a large number of trains can we organize our advance depôts with necessary rapidity, and move them to fresh points. The demand for trains is greatest on those days when fighting is in progress. A number of urgent demands—amounting sometimes to hundreds during two or three days—are made, not only for supplies, but for the carriage of military and engineer stores, troops, parks, and the transport of drafts and of wounded. The needs of an army in war are so varied and so vast that it is considered necessary in Europe to have for each army corps a special line of rails (single track), capable of running 14 to 20 pairs of trains in the 24 hours. For our 9 army corps we have only one single line of rails running (in the last few weeks) from 8 to 10 pairs of trains. The inability of the line to cope with the necessities of the war is the main reason for the slow and indecisive nature of the campaign. Our reinforcements arrive in driblets. Supplies despatched from Russia in the spring are still on the Siberian line. Waterproofs sent for the summer will arrive when we want fur coats; fur coats will be received when waterproofs are wanted. But so far, during all these months that we have been in contact with the enemy, have fought and have retired, we have not been hungry, because we have been living on the country. The situation is now altogether changed, for local resources will last only for a short time longer. Our horses will soon have to be fed on hay and straw, and if we do not make extraordinary efforts to improve the railway and concentrate a large quantity of supplies at the advanced base, our men, who are concentrated in great numbers on small areas, will, after the horses, begin to suffer hardship and hunger, and will fall sick. Any accidental damage to the railway will be sorely felt.

“I am expressing my firm conviction with complete frankness as the officer in command of three armies, that, for their successful operations, we must at once start laying a second track throughout the whole Siberian trunk line and on the Eastern Chinese Railway. Our army must be connected with Russia by a line capable of running 48 pairs of trains in the day.

“I have some experience of my profession, and was for eight years in charge of the management of the Trans-Caspian Railway, and I am convinced that all these difficulties can be overcome if Your Majesty is pleased to order it. Possibly the war will be finished before we shall have laid the second line of rails over more than a fraction of the whole distance; on the other hand, it may continue so long that only a double track will save the situation. Only with a double line also shall we be able at the end of the war to send back rapidly all the troops which came from Russia and to demobilize. We are living in the midst of events of immense importance on which depends the future, not only of the Far East, but, to a certain extent, that of Russia. We must not shirk sacrifices that will insure victory and subsequent peace in the Far East. Neither a conquered Japan nor a sleeping China will permit such peace unless Russia possesses the power to despatch army corps to the Far East more rapidly than she can at present. A double line alone will enable this to be done. While keeping this as our main ultimate object, we should make every effort now to work the railways up to a traffic capacity of 14 pairs of trains as far as Harbin, and 18 beyond.

“Having set to work to double the line, we must try to arrange that one section will give us 18 pairs of military trains a day (perhaps it will be best to begin from the hilly portions). As the second line is laid, we shall be able to work up to a running and carrying capacity along the whole line to Harbin and southwards of at first 24 pairs of trains, then 36, and eventually 48.”

Upon receipt of this letter from me, the first thing that the St. Petersburg authorities did was to work out the details of the preliminary arrangements for doubling the line. They tried to formulate some scheme whereby the necessary construction material could be carried on the railway without cutting down the number of troop trains. It was suggested that the rails should be sent via the Arctic Ocean, and apparently some attempt to do this was carried out, but later all idea of doubling the line during the war was abandoned. It was a pity, for the earth-work might have been carried out without interfering with the traffic. Had we carried out this important measure, we should have made our position in the Far East far stronger than it is now.

While they were making ready for war with us, the Japanese concluded a treaty with Great Britain, by which they were assured of the non-interference of any other Power. We, on the contrary, had not only made no preparations for war in the east, but did not even consider it possible to weaken to any great extent our frontiers on the west, in the Caucasus, or in Central Asia. Our diplomats neither steered clear of war with Japan, nor insured against interference in the west. The result was that, while Japan advanced against us in her full strength, we could only spare an inconsiderable portion of our army in European Russia to reinforce the Far East. We had to fight with one eye on the west. The army corps stationed in Western Russia were in a much higher state of preparation than those in the interior as regards the number of men in the ranks and the number of guns, horses, etc., and they were armed with quick-firing guns. We, however, took corps that were on the lower peace footing (the 17th and 1st), and gave them artillery from the frontier corps; while the efficiency of some of the units we took, which had companies from 160 to 100 strong in peace-time, varied a great deal. It was due to this quite natural fear for our western frontier that of five army corps sent to the Far East, three were composed of reserve divisions. We had to keep troops back for the maintenance of internal order; Japan did not have to do this. Our picked troops—the Guards and Grenadiers—were not sent to the front; on the other hand, the Japanese Guards Division was the first to attack us at the Ya-lu. Thus, though we had a standing army of 1,000,000 men, we sent reserve units and army corps on the lower establishment to the front, and entrusted the hardest work in the field, not to our regular standing army, but to men called up from the reserve. In a national war, when the populace is fired with patriotism, and everything is quiet in the interior of the country, such a course might be sound; but in the war with Japan, which was not understood, and was disliked by the nation, it was a great mistake to throw the principal work on to the reserves. In the summer of 1905 we corrected this mistake, and filled up the army with young soldiers, with recruits of 1905, and drafts from the regular army. These young soldiers arrived at the front cheerful and full of hope, and in a very different frame of mind to that of the reservists. It was a pleasure to see the drafts of regulars proceeding by train to the front—they were singing and full of spirit. The majority of them were volunteers, and they would undoubtedly have done magnificently if they had had a chance, but more than 300,000 of them saw no service owing to the hasty peace.

In her war with France in 1870, Prussia, assured of our neutrality, had nothing to fear from us, and was able to leave only an inconsiderable number of men on our frontier and to enter upon the struggle with all her strength. Similarly, Japan was able to throw her full strength into the struggle from the very commencement. We, on the other hand, considered it advisable to keep our main forces in readiness in case of a European war, and only a small part of the army stationed in European Russia was sent to the Far East. Not a single army corps was taken from the troops in the Warsaw Military District, our strongest garrison. Even my request to send the 3rd Guards Division to the front from there was not granted, while our numerous dragoon regiments were represented by a single brigade. We kept our dragoons on the western frontier, and sent to the war the 3rd Category regiments of the Trans-Baikal and Siberian Cossacks, consisting of old men mounted on small horses. They reminded one more of infantry soldiers on horseback[84] than of cavalry. In my report to the Tsar on March 7, 1904, I requested that the reinforcements from Russia might be mobilized simultaneously and immediately after the Easter holidays, and I gave the following reasons:

“By this measure the units, especially the reserve ones, will get time to settle down. It will also be possible to put them through a course of musketry and some military training, and it will give time to organize the transport, parks, and hospitals.”

I considered it important that units detailed for the Far East should have as long as possible to shake down, and to receive some training before starting for the front.

The above memorandum, with the Tsar’s remarks on it, was sent to the War Minister for his guidance; but General Sakharoff either did not carry out some of the important recommendations I had emphasized most, or altered them, and carried them out too late. As regards the date of mobilizing the reinforcements, he did not share my view (1) as to the necessity for a simultaneous mobilization, and (2) as to the necessity for mobilizing immediately after Easter. In a memorandum drawn up by him, dated March 18, 1904, he asked permission to mobilize the reinforcements in three lots instead of at once. Six Cossack regiments were first of all detailed for mobilization in the end of April, then the 10th Army Corps on May 1, the 17th Army Corps on May 1 or a little later, and four reserve divisions of the Kazan Military District at the end of June. In a second memorandum (July 31) the question was again raised whether all the reinforcements should be mobilized simultaneously or at different times. The Headquarter Staff preferred the latter alternative. Besides the poor carrying capacity of the Siberian Railway, the reason given was that—“… The political horizon might become so clouded as to make the simultaneous mobilization of all the troops mentioned in the statement inadvisable.”

Notes:

[76] [On March 10, 1905, the battle of Mukden, which had lasted for several days, ended with the retreat of the Russians and the occupation of Mukden by the Japanese. On the 16th the Japanese entered Tieh-ling, and on the 21st Chang-tu Fu. The latter represents the furthest point reached in the northerly advance of their main armies.—Ed.]

[77] [General Kuropatkin’s country estate in Russia.—Ed.]

[78] “Scheme for the Strategical Distribution of Troops in the Far East in the Event of War with Japan,” November 18, 1900 (Port Arthur).

[79] [Being a single-line railway, the number of trains in one direction depended on those travelling in the opposite direction; they are, therefore, alluded to in pairs. A pair of trains implies two trains, one each way.—Ed.]

[80] [? Eastern Chinese Railway.—Ed.]

[81] [An échelon of troops consisted of the troops from a certain number of trains.

[82] [The Eastern Chinese line was under the Minister of Finance.—Ed.]

[83] [A strategic line of railway in European Russia, some 700 miles long.—Ed.]

[84] [General Kuropatkin does not refer to mounted infantry.—Ed.]

Autore: Alekseĭ Nikolaevich Kuropatkin

Fonte: The Russian Army and the Japanese War, Vol. I (Chapter VIII)

Lascia un commento