Warfare exists in the realm of both art and science – as a phenomenon in which sensing and intuition (in other words, art) play a complementary role to education and training (science). Just as a painter must have more than one color on his pallet, the practitioner of warfare must understand more than one form of warfare to be effective on the battlefield. However, the emphasis on maneuver warfare in current U.S. Army doctrine, at the expense of other forms of warfare, limits Armor and Cavalry leaders’ ability to be true artists in warfare by not fully educating and training them on the realities of warfare, thus negatively influencing their ability to sense and apply intuition in battle. Doctrine’s focus on maneuver warfare lies at the heart of this conundrum.

The term maneuver is regularly misapplied throughout U.S. Army doctrine, diluting the true intent of the concept, creating misconceptions about its utility and role in warfare. Furthermore, it can be argued that a mentality has emerged within the U.S. Army that places maneuver warfare at the apex of the forms of warfare, elevating it to a position of near-panacea status, which further removes the concept from individual and institutional understanding.

In essence, the U.S. Army’s interpretation of the maneuver-warfare concept has created a solution looking for a problem. With that in mind, maneuver should not be viewed as an end unto itself but instead as a component in a three-part construct that oscillates among maneuver, positional and attrition warfare as battlefield conditions dictate (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Maneuver-positional-attrition triad.

To be sure, positional and attrition warfare are alive and well in modern combat. The Russo-Ukrainian War’s major battles – including the Battle of Ilovaisk, the Second Battle of Donetsk Airport and the Battle of Debal’tseve – are a testament to the continued efficacy of positional and attrition warfare, as are combat operations in Syria – including the siege of Aleppo and the contentious clearance of Islamic State fighters from the city of Mosul and western Iraq.1

To support that position, this article examines maneuver-warfare theory and the U.S. Army’s interpretation thereof. Next, this article illuminates the errors in a maneuver-centric approach to warfare while using Napoleon Bonaparte’s Ulm-Austerlitz campaign to illustrate the utility of a maneuver-positional-attrition warfare dynamic. The article concludes by recommending a reframing of the method in which doctrine describes, and Armor and Cavalry leaders think about, operations and tactics to bring it more in line with the praxis of warfare.

From theory to doctrine

Understanding the theoretical vision of maneuver warfare is fundamental in gaining an appreciation of the concept. The modern maneuver-warfare paradigm is chiefly a byproduct of World War I, a conflict largely characterized as a mass slaughter.2 Historians Martin Blumenson and James Stokesbury suggest that the primacy of artillery and machineguns on the battlefield in opposition to light infantry and horse cavalry all but removed mobility from the battlefield, creating what they characterized as a “mass slaughter of innocents, in which neither side could or would turn off the tap of blood.”3

In response to the bloodletting of World War I, two British theorists came to the fore: J.F.C. Fuller and B.H. Liddell Hart. Following the war, Fuller and Liddell Hart developed cogent theories for moving beyond the bloody stalemate of World War I’s Western Front. Their theories were underpinned by combining nascent technology – the tank and airpower – with infantry to restore mobility to the battlefield, the goal being to strike fear into the opponent through shock effect, causing the belligerent to acquiesce with little loss of life to either party.4

Blumenson and Stokesbury echo this position in writing that, “[i]n the realm of military technology, things were being done to restore mobility to warfare, and in effect to make wars winnable again.”5 More to the point, Fuller and Liddell Hart’s early work was the nucleus from which contemporary maneuver warfare theory and doctrine evolved.

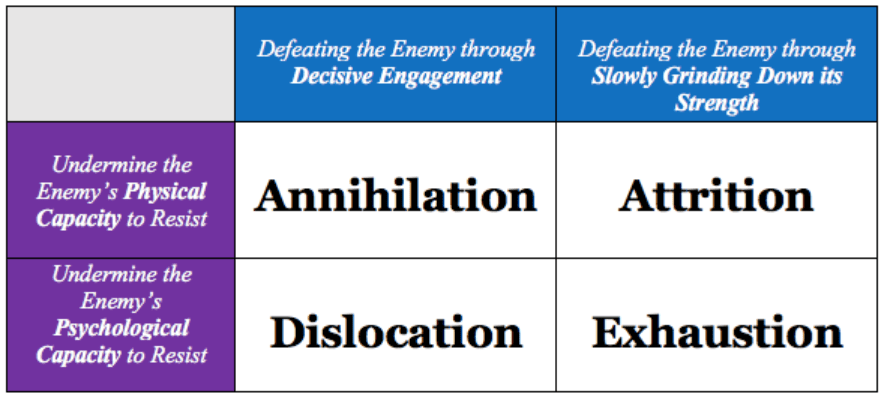

From the standpoint of theory, modern maneuver warfare has two goals: (1) to achieve a psychological impact on an adversary – to create panic, or cognitive paralysis, forcing the enemy’s will to resist to collapse; and (2) to gain and maintain a position of relative advantage in relation to a belligerent. Creating confusion (a cognitive effect) and disorganization (a physical effect) are subordinate goals of maneuver warfare that contribute to the concept’s overarching aims. The idea of defeating the enemy through the most economic use of force is closely aligned with both of these goals.6

Maneuver seeks to accomplish this through surprise gained by rapid tactical and operational tempo, or by attacking from unexpected directions or locations. More to the point, combined-arms and joint operations are fundamental to maneuver warfare, as they enhance the maneuvering force’s ability to put physical and temporal distance between them and the enemy, thus enabling their own mobility. Effective reconnaissance-and-security operations are essential to maneuver warfare, as they provide the force the information needed to enable maneuver, the most significant information being:

(1) advantageous movement corridors and

(2) the most profitable positions at which to strike against a belligerent.

U.S. military doctrine, as it relates to maneuver warfare, focuses on a psychological effect at the joint and operational levels and predominately a physical effect at the tactical level.7 Joint doctrine posits that maneuver warfare seeks above all else to strike at the psychological will of an opponent – to put them in a position so disadvantageous they give up the will to resist. Explicitly linked to the idea of psychological acquiescence is that of deftly moving to a position of relative advantage, with minimal direct combat engagement along the way, to place oneself at a point in time, space and counter-purpose to force the belligerent’s hand in giving up the battle without having to fight.8

The Army’s doctrine differs slightly from joint doctrine, stating that maneuver is the use of forces in an operational area through the combination of movement and firepower to gain a relative position of advantage in relation to an

adversary.9 Meanwhile, contemporary American military theorist Robert R. Leonhard defines maneuver as placing “[t]he enemy in a position of disadvantage through the flexible application of combat power.”10 The idea of gaining a position of relative advantage is the glue that binds each of those definitions, whether the desired effect of that is a psychological or physical impact.

Solution looking for a problem

A major problem with the U.S. Army’s interpretation of maneuver warfare is the primacy it ascribes to the concept, placing it in a position above all other forms of warfare. In doing so, it turns a blind eye to the role battlefield conditions play in shaping the conduct of battles, operations and campaigns. Moving beyond the theoretical ruminations and archetypal stylings of doctrine, one quickly finds that the conduct of battle, operations and campaigns consists of an interchange among maneuver warfare, positional warfare and attrition warfare.

Though not defined doctrinally, positional warfare can be defined as the use of force – through tactics, firepower or movement – to move an opponent from one position to another for further exploitation or to deny them access to an area for further exploitation – while attrition warfare can be defined as the methodical use of battle or shaping operations to erode or destroy a belligerent’s equipment, personnel and resources at a pace greater than they can replenish their losses. The goal of attrition is to wear down the belligerent to the point they can no longer continue to resist or are physically destroyed, while the goal of positional warfare is to place one’s self in a position of advantage in relation to the belligerent or to lure the belligerent into vacating their own position of relative advantage in relation to one’s own force. It is also important to understand that both positional and attrition warfare are offensive and defensive, not just defensive, as some commenters contend.11

The interchange among maneuver, positional and attrition warfare is predominately driven by the desired effect – in situations where tempo is the goal, maneuver is the preferred method; in situations where overwhelming firepower is required, attrition is the preferred method; and in situations where an advantageous position is sought, or an enemy must be pulled from its current position to one of the attacking force’s choosing, positional warfare is employed. Yet it must also be understood that this trade-off depends on more than just the object but also on the conditions: environmental, enemy-focused, friendly focused and internally focused.12

At a more granular level, contemporary U.S. Army doctrine possesses a series of fundamental flaws:

- It fails to account for warfare’s conditional character, which dictates the form of warfare to be employed, and instead elevates maneuver warfare to the sole form of warfare to be employed;

- It continually conflates maneuver (the action) with maneuver warfare (the theory of battle and operations); and

- It suggests a universality of the theory in relation to armor, cavalry and infantry formations.

To be sure, the previous points do not constitute a comprehensive list of doctrine flaws associated with maneuver warfare. Nonetheless, these flaws create misconceptions about the utility of maneuver warfare, further obscuring the relevance of positional and attrition warfare. These flaws also force maneuver into situations for which it is ill-suited and indirectly cause leaders to project a “maneuver-centric” approach on belligerents, leading commanders and staffs to misunderstand enemy actions, intentions and will, which is counterproductive for any professional Soldier.

Blumenson and Stokesbury suggest that, “[o]ne of the most important of these (i.e. professional abilities) is the ability to see the situation through the eyes of the enemy; Napoleon called this ‘seeing the other side of the hill.’”13 To see the other side of the hill, Armor and Cavalry leaders must understand that maneuver might be the U.S. Army’s preferred method of warfare, but it is by no means the only way of fighting, nor necessarily the best method of warfare.

Examining flaws

Maneuver is conditional; it is not an end unto itself. Maneuver is dependent on a variety of factors, both standalone and interdependent. While not a complete list, maneuver depends on the following factors:

- Accurate information pertaining to the enemy’s location (in other words, a movement-to-contact is a form of attritional warfare, at least initially);

- Tactical and operational mobility, enabled by tactical and operational communications systems;

- Favorable terrain that is open and does not canalize the attacking force;

- Directive command and control, and a culture that embodies trust and underwrites risk;

- Reaction time and space, usually a byproduct of effective reconnaissance, security and shaping operations;

- Mobile sustainment infrastructure; and

- Proficient formations, well-versed in choreographed and rehearsed battle drills

The conditional character of maneuver warfare illustrates that maneuver is not always the ideal, most efficient or most profitable method of engaging in combat. This dynamic necessitates that maneuver warfare not be viewed as an end unto itself, but instead, maneuver should be viewed as but one component of a larger whole, of which positional warfare and attrition warfare constitute the other parts. This maneuver-positional-attrition warfare construct interacts with the battlefield’s conditions to determine the most suitable method of warfare. The formation’s structure and its mission also influence the form of warfare to be employed.

Compounding the aforementioned problem is the conflation of the physical act of maneuvering with the theoretical and doctrinal construct of maneuver warfare. In many cases, the term maneuver is used to describe the physical act of moving from one place to another, or moving from one place to another through difficult terrain. As mentioned previously, the Army defines maneuver as the employment of forces in an operational area through the combination of movement and firepower to achieve a position of relative advantage in regard to a belligerent.14 Yet the term maneuver is often applied incorrectly and out of context, thereby distorting the utility of the term itself. While the term could be used to define these actions, it misapplies or misuses the term as it applies to the doctrinal definition and as it relates the associated theory of warfare.

Furthermore, the Army’s use of the term maneuver has caused the term to become polysemic, meaning that the word possesses multiple meanings or definitions.15 The polysemic character of maneuver, as used within Army doctrine, is an outgrowth of attempts to nest words, phrases and concepts within doctrine, which has diluted the meaning of the concept even further. A synonym to polysemic is “word creep.”16 Word creep has led to the term maneuver being used to define everything from straight-line movement, to movement over restricted terrain, to complicated combined-arms operations directed against a skillful opponent. Word creep of the term maneuver has ripple effects; it distorts doctrine, which in turn, creates misconceptions about the concept, hampering understanding of the idea of maneuver across the force.

Also, word creep has distorted the application of the word “maneuver” in relation to the concept of maneuver and maneuver warfare. Specifically, the nesting of the term throughout doctrine has yielded terms like “maneuver units,” which is a misnomer. Terms like this imply that those formations are only capable of conducting maneuver, but as has already been established, understanding beyond maneuver is required.

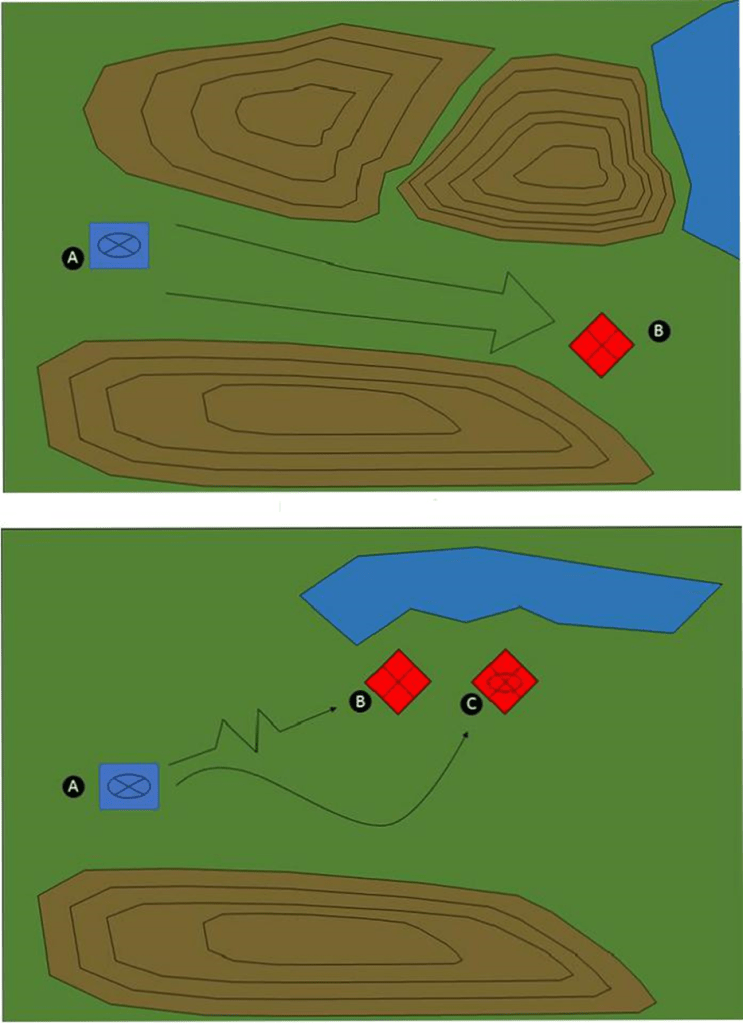

Yet, even within U.S. Army doctrine, positional and attrition warfare are hidden in tactics and operations. For instance, moving from Point A and attacking forces at Point B along one or two highly canalized avenues of approach with combined arms and joint capabilities is not maneuver – this approach is attrition warfare (Figure 2). Furthermore, moving from Point A to fix an opponent at Point B, then to conduct a flank attack with a portion of one’s force at Point C, is not maneuver either – this is also an attritional attack (Figure 3).

Attrition warfare (Figure 2)

Attritional attack (Figure 3)

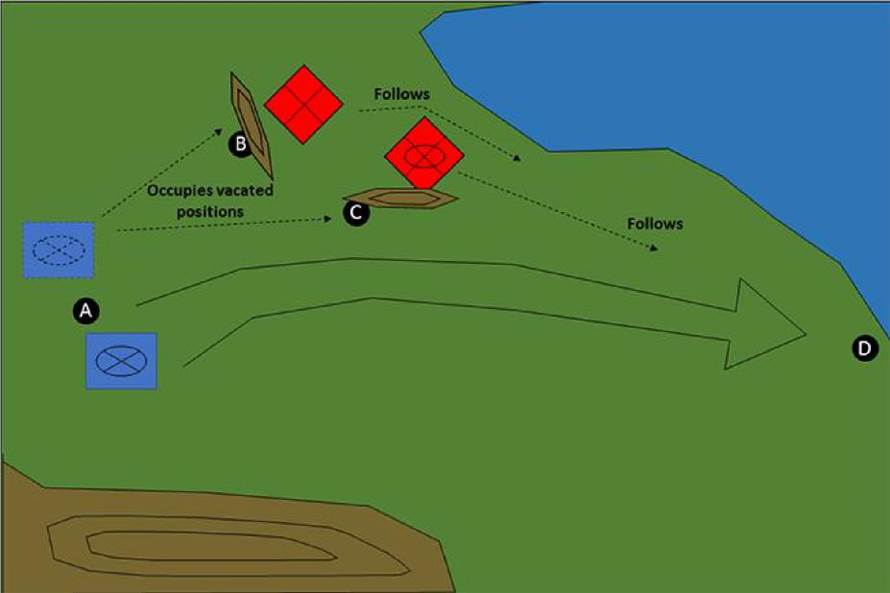

Lastly, moving from Point A toward Point D with high tempo, in an attempt to pull an opponent from Point B or C – which may or may not be subsequently occupied by a portion of one’s own force – is not maneuver; this is a form of positional warfare (Figure 4).

Positional warfare.(Figure 4)

The examples described are simplified versions of schemes of maneuver often found in U.S. Army operations orders, but it is easy to see that these “maneuvers” are often positional or attrition warfare. A deeper examination of U.S. Army doctrine, specifically in regard to the forms of maneuver, yields similar findings.

The Army’s forms of maneuver – penetration, infiltration, turning movement, flank attack, frontal attack and envelopment – are also incorrectly characterized as maneuver. To be sure, a turning movement and infiltration are arguably forms of positional warfare, while penetrations, frontal attacks and flank attacks are blatant forms of attritional warfare. An envelopment is the only form of maneuver which can truly be categorized as maneuver.

Pointing this out illuminates the fact that belies U.S. Army doctrine: attritional and positional warfare play an equal, if not greater, role in battles and operations than does maneuver warfare. This is not to condemn or venerate any one form of warfare over another, but instead to illustrate the utility and efficacy all three forms of warfare – maneuver, positional and attrition – have in relation to the conduct of warfare.

The last misconception to dispel is that maneuver is universal to Armor, Cavalry and infantry formations. A common trope heard around the combat-arms units is that “maneuver is maneuver.” However, this supposition is fundamentally incorrect because it infers that all formations are capable of conducting maneuver warfare, regardless of their composition. This position overlooks the conditional character of maneuver warfare, which demands unique capabilities to conduct the concept.

The implication of this is that maneuver warfare is only conducted by formations possessing the requisite capabilities within the corresponding battlefield conditions. Maneuver warfare requires rapid mobility, enhanced by foreknowledge of the adversary’s location. Mobility in maneuver warfare allows one to strike out for positions of relative advantage or situations in which to create shock or chaos in the adversary’s formations.

The absence of rapid mobility prevents a force from conducting maneuver warfare, therefore pure light forces possess only a limited ability to conduct maneuver warfare. Furthermore, cavalry formations – serving as the eyes and ears of the main body, enabling reaction time and space – do not conduct maneuver. Cavalry formations instead conduct enabling or shaping operations for main-body forces, who in turn conduct operations in line with one of three forms of warfare based on battlefield conditions. Therefore, maneuver is not inherent to Armor, Cavalry or infantry formations.

As a result of these misconceptions about maneuver warfare, maneuver’s primacy in U.S. Army doctrine generates counterproductive thinking in relation to understanding the character of a given tactical problem. The byproduct of unclear thinking is difficulty in developing realistic solutions and implementing those solutions in a meaningful manner. What is important is tactical combined-arms proficiency because it is relevant to all components of the maneuver-attrition-positional warfare triad. Terrain, the enemy or friendly conditions will influence the method of fighting, but combined-arms action will be inherent in whichever scenario presents itself.

With this in mind, doctrine would be better served if it embraced the usefulness of all three forms of warfare instead of viewing maneuver warfare as the silver bullet for operational and tactical success in relation to conventional operations. Similarly, the maneuver-attrition-positional triad will potentially lessen the U.S. Army’s proclivity in projecting its own fighting paradigm – maneuver warfare – on its opponents. The result of this will be Armor and Cavalry leaders better prepared to understand a belligerent’s probable intentions and plans.

Selection process for the forms of warfare (Figure 5).

Therefore, as an institution, the Army should reframe how it thinks, writes and speaks about conventional combat operations. A starting point would to restructure Army doctrine to account for the interdependent relationship among maneuver warfare, positional warfare and attritional warfare. To do so, adjusting the concept of “forms of maneuver” to “methods of operations” would be a start, and then within that category place the forms of operations and their derivative forms of action.

History offers many examples of successful battles, campaigns and operations. The argument can be made that most great campaigns are the result of blending maneuver, positional warfare and attrition based on a forces’

inherent capabilities applied to the battlefield conditions. Few campaigns in history illustrate this dynamic better than Napoleon Bonaparte’s Ulm-Austerlitz Campaign (1805) from the War of the Third Coalition (1803-1806), in which France faced off against a multi-nation European alliance.17 The campaign is instructive because it clearly shows the interconnected relationship among maneuver, positional and attrition warfare, and how each supported the other, enabling victory in respective aspects of the campaign.

Ulm-Austerlitz Campaign

Napoleon’s Ulm-Austerlitz Campaign is arguably one of the best examples demonstrating the interdependent relationship among maneuver warfare, positional warfare and attrition warfare. Napoleon’s 1805 campaign consisted of two major engagements: the first at Ulm and the second at Austerlitz.18

The Battle of Ulm is perhaps the historical apogee of maneuver warfare. Ulm was less a battle per se and more a small collection of engagements Oct. 16-19, 1805. The Austrians, largely unaware of Napoleon’s main body thanks to his effective use of terrain, cavalry, mobility and tempo, were completely encircled at Ulm. Upward of 25,000 Austrian soldiers under the command of GEN Karl Mack von Leiberich surrendered there (Figure 6).19

Preeminent Napoleonic warfare scholar David Chandler wrote about Ulm: “Nevertheless, Napoleon had achieved a great victory on the Danube, and although six weeks later it was to be overshadowed by an even greater triumph, the magnitude of the capitulation of Ulm must be acknowledged. … The demoralization consequent upon discovering a powerful enemy on his [von Leiberich’s] rear had played a decisive part in paralyzing the victim, while the deficiencies of the Austrian system of command and their fatal miscalculations concerning the proximity of their Russian allies had made the catastrophe practically inevitable.”20

The Ulm Campaign, Central Europe, 1805. (Figure 6)

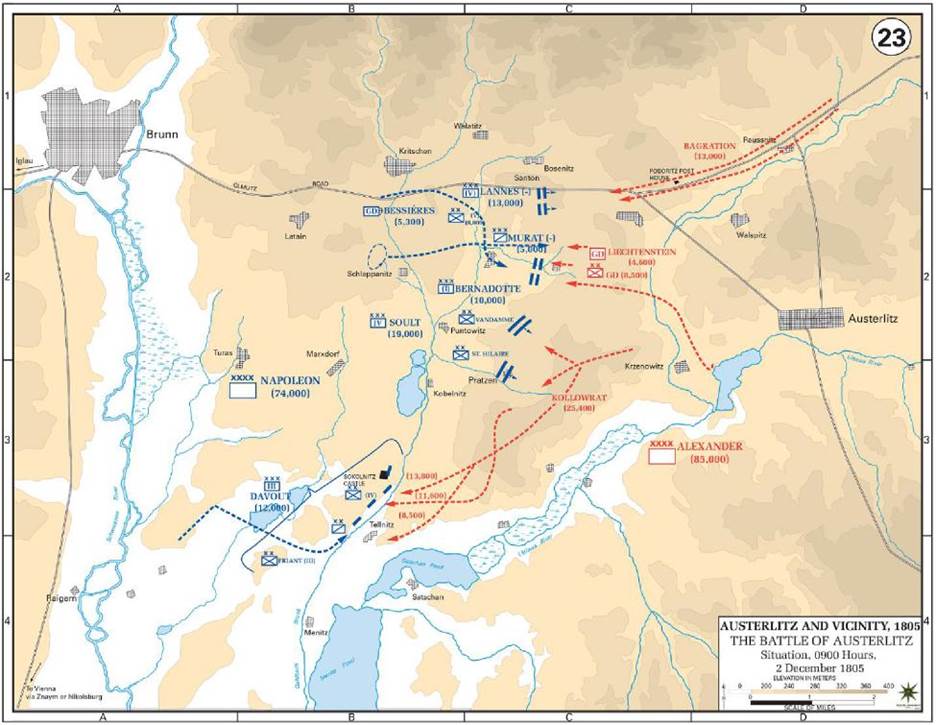

The Battle of Austerlitz, fought Dec. 2, 1805, was fundamentally different from Ulm in that it was at first a positional contest before shifting to a battle of attrition. Napoleon, feigning weakness around the Pratzen Heights, set his force in what the Austro-Russian coalition perceived to be a vulnerable position. In doing so, the coalition, under command of Russian Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov, played into the trap Napoleon set. Bonaparte then unleashed his force to bludgeon the Austro-Russian armies through an attritional battle focused on annihilation. Napoleon’s use of positional warfare – using tactics or one’s own position to draw a belligerent into a desired location – set the Austro-Russian coalition up for the battering it faced on the Pratzen Heights (Figure 7).

Chandler concludes his discussion on Austerlitz by saying, “11,000 Russians and 4,000 Austrians lay dead on the field, and a further 12,000 Allied troops were made prisoner, together with 180 guns and 50 colors and standards. Thus the Austro-Russian army lost some 27,000 casualties – or one-third of its original strength. The French, however, escaped relatively lightly: perhaps 1,305 were killed, a further 6,940 wounded and 573 more captured.”21

The Battle of Austerlitz, Austerlitz and vicinity. (Figure 7)

The result of the Battle of Austerlitz, arguably Napoleon’s finest battle, was that “Napoleon had gained his decisive victory, and it duly brought his campaign to a triumphant conclusion.”22 The nuance of the campaign highlighted the utility and interplay among maneuver, attrition and positional warfare. Ulm was largely the success of an effective mix of maneuver and positional warfare, while Austerlitz was a brilliant battle because of the balancing of positional and attrition warfare.

Historian Martin van Creveld postulates that positional and attrition warfare, not maneuver warfare, were Napoleon Bonaparte’s primary methods of warfare. Creveld states, “Napoleon’s system of warfare was based on decisive battles. Not for him were either bloodless maneuvers … or protracted struggles of attrition. … He aimed at first pushing his opponent into a corner from which there was no escape, then battering him to pieces.”23

The game of football offers useful parallels for the practitioner of warfare. The idea of blending forms of warfare correlates to the manner in which an offensive coordinator blends run and pass plays. Within each of those categories nuance is found as well. The run game blends inside, outside and draw plays, while the passing game mixes in a variety of short, long and screen passes. The goal is to be multi-dimensional. Napoleon’s Ulm-Austerlitz Campaign is an excellent example of the benefit in being multi-dimensional in the conduct of warfare. The U.S. Army’s sole focus on maneuver warfare is a prime example of a football team that seeks a touchdown every play by throwing deep but ends up having to punt on almost every fourth down.

Conclusion

Robert M. Citino, writing about the flaws in the German tactical and operational doctrine of World War II, warns, “Nevertheless, there is something incomplete about a way of war that relies on the shock value of small, highly mobile forces and airpower, that stresses rapidity of victory over all, and that then has a difficult time putting the country it has conquered back together again.”24

He continues by discussing the tactical and operational problems posed by the rapid defeat of the Yugoslav army in April 1941, stating that, “The Wehrmacht had overrun Yugoslavia in record time and with ease. It had dismantled a million-man army. … Its own casualties were just 151 dead.”25 The problem, according to Citino, was that, “The Germans had advanced so far and so fast that they left numerous loose ends. Yugoslav soldiers cut off from their units soon took to the mountains to form resistance bands, and the Germans would find themselves conducting an anti-partisan campaign for the rest of the war.”26

The U.S. Army’s predilection for maneuver warfare, while turning a blind eye to the usefulness other forms of warfare, including positional and attrition warfare, has left the Army looking like the German army after the toppling of Yugoslavia in Spring 1941. The U.S. Army has chalked up many brilliant tactical victories in Afghanistan and Iraq through shock, mobility and joint firepower in relatively quick time, but like the Germans, also left many loose ends that have allowed operational and strategic victory to slip away. As such, the time has come to take a much broader look at how we think about the conduct of warfare.

Regardless of whether or not doctrine shifts to account for the realities of warfare, students and practitioners of warfare must widen the aperture through which they view the conduct of battle and operations. To that end, British military theorist and general officer Fuller wrote that, “If we wish to think clearly, we must cease imitating; if we wish to cease imitating, we must make use of our imagination.”27 With this in mind, Armor and Cavalry leaders must understand that maneuver should not be viewed as an end unto itself, but instead as a component in a three-part construct that oscillates among maneuver, attrition and positional warfare. Maneuver warfare is not a silver bullet or the way, but rather conditional, and complements other forms of warfare.

The oscillation among these components is dependent on the relationship among battlefield conditions, the formation’s mission and the formation’s inherent capabilities – Armor and Cavalry leaders must understand that maneuver is both a theory of warfare (in other words, a theory about how to fight) and a discrete action.

What’s more, Armor and Cavalry leaders must understand that the common trope “maneuver is maneuver” is fundamentally incorrect and potentially dangerous. Maneuver in both function and theory is fundamentally rooted in the type of formation being employed, and in the case of contemporary U.S. Cavalry formations, not a skill they conduct but rather one in which they enable.28 Therefore, it is imperative for the Armor and Cavalry leader to understand that maneuver is but one way to think about fighting and a component of a larger whole in regard to the physical conduct of warfare. In doing so, they will better understand enemy intentions and actions.

Lastly, it is important to remember that the conduct of warfare is far more art than science. Therefore, Armor and Cavalry leaders must avoid prophecies of deliverance through theories, doctrines and technology. Instead, Armor and Cavalry leaders must understand the character of the engagements, battles and operations to develop doctrines better grounded in the realities of warfare. Similarly, Armor and Cavalry leaders must understand the conditional character of the engagements, battles and operations in which they find themselves to apply the reciprocal form of warfare to maximize their effect on the enemy.

Conversely, Armor and Cavalry leaders must not project their own paradigm of action on a given enemy because doing so will likely lead to misjudging how the belligerent will engage in combat. Armor and Cavalry leaders must

understand that their adversaries will seek to dislocate U.S. Army forces or to render a belligerent’s strength irrelevant.29 Belligerents will seek to dislocate an adversary positionally, functionally or temporally.

Positional dislocation – or the art of rending a belligerent’s advantages irrelevant by causing it to be in a disadvantageous location, disposition or orientation – is most often achieved through positional warfare.

Closely related to positional dislocation, functional dislocation renders a belligerent’s advantages nil by causing an adversary to fight in a manner for which it is not suited or designed to fight. In most cases, functional dislocation is achieved through the attrition or maneuver warfare, both of which negate the conditional component to an adversary’s strength.

Temporal dislocation – or maximizing the temporal characteristics of warfare (in other words, duration, frequency, sequence and time-based opportunity) to negate a belligerent’s strengths – is achieved through the use of maneuver.30

All of which is to say, Armor and Cavalry leaders must remain aware of the role positional and attrition warfare play in relation to maneuver warfare and that turning a blind eye to those forms of warfare is counterproductive. Maneuver warfare is not a silver bullet and should not be perceived as the answer, but rather one of many solutions to problems faced by commanders on the battlefield.

Notes:

1 For more information on the Russo-Ukrainian War, see the author’s “Making Sense of Russian Hybrid Warfare: A Brief Assessment of the Russo-Ukrainian War,” The Land Warfare Papers, No. 112, March 2017 (coauthored with MAJ Andrew Rossow) and the author’s “Battle of Debal’tseve: the Conventional Line of Effort in Russia’s Hybrid War in Ukraine,” ARMOR, Winter 2017.

2 Steven T. Ross, “Napoleon and Maneuver Warfare,” in The Harmon Memorial Lectures in Military History, 1959-1987, edited by Harry R. Borowski, Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, U.S. Air Force, 1988.

3 Martin Blumenson and James Stokesbury, Masters of the Art of Command, New York: Da Capo, 1990 (originally published in Boston by Houghton Mifflin, 1975).

4 Azar Gat, A History of Military Thought: From the Enlightenment to the Cold War, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

5 Blumenson and Stokesbury.

6 William Lind, “The Theory and Practice of Maneuver Warfare,” in Richard D. Hooker, editor, Maneuver Warfare: An Anthology, Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1993.

7 The tactical level is also aware of the psychological component of maneuver warfare, but at a far lesser degree than the operational level.

8 Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2017.

9 Army Doctrinal Reference Publication (ADRP) 3-0, Operations, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2016.

10 Robert R. Leonhard, The Principles of War for the Information Age, Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1998.

11 Several authors – including Robert Citino and Lawrence Freedman – suggest that attrition and positional warfare are predominately static, defensive forms of fighting.

12 The argument can be made that maneuver warfare is a sub-component of positional warfare due to its focus on physical and temporal positions in relation to an adversary. However, that discussion exceeds the scope, scale and purpose of this article.

13 Blumenson and Stokesbury.

14 ADRP 3-0.

15 https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/polysemous.

16 Word creep is defined by the author as the gradual broadening of the original definition of a word or concept. The definition is an off-shoot of mission creep, which is defined as the gradual broadening of the original objective of a mission or organization. See https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mission%20creep.

17 Nations included Great Britain, Russia, Austria, Sweden and the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily. See David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon, New York: Scribner Press, 1966.

18 The campaign consisted of several smaller battles along the way, those battles helping shape the major battles. However, a discussion of these battles is left out of this article because they do not provide much addition to the discussion.

19 Chandler.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Martin van Creveld, Command in War, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985.

24 Robert M. Citino, Death of the Wehrmacht: The German Campaigns of 1942, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 J.F.C. Fuller, Generalship: Its Diseases and Their Cure, A Study of the Personal Factor in Command, London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1936.

28 Looking beyond the U.S. Army, the traditional role of the cavalry was far greater than that of just reconnaissance and security operations. The traditional role of cavalry operations focused on reconnaissance, security, quick-strike direct attacks / penetrations, envelopments and, as the exploitation force, viciously pursuing a fleeing enemy to scythe them down as they retreated. The U.S. Cavalry has all but eliminated the capability to conduct quick-strike direct attacks / penetrations, envelopments and pursuit by focusing – in doctrine, force structure and education/training – solely on reconnaissance and security.

29 Leonhard.

30 Ibid.

Acronym Quick-Scan

ACR – armored cavalry regiment

ADRP – Army doctrinal reference publication

SAMS – School of Advanced Military Studies

Autore: Lt. Col. Amos C. Fox, PhD, U.S. Army, Retired

Fonte: ARMOR Fall 2017

Lascia un commento