Introduction

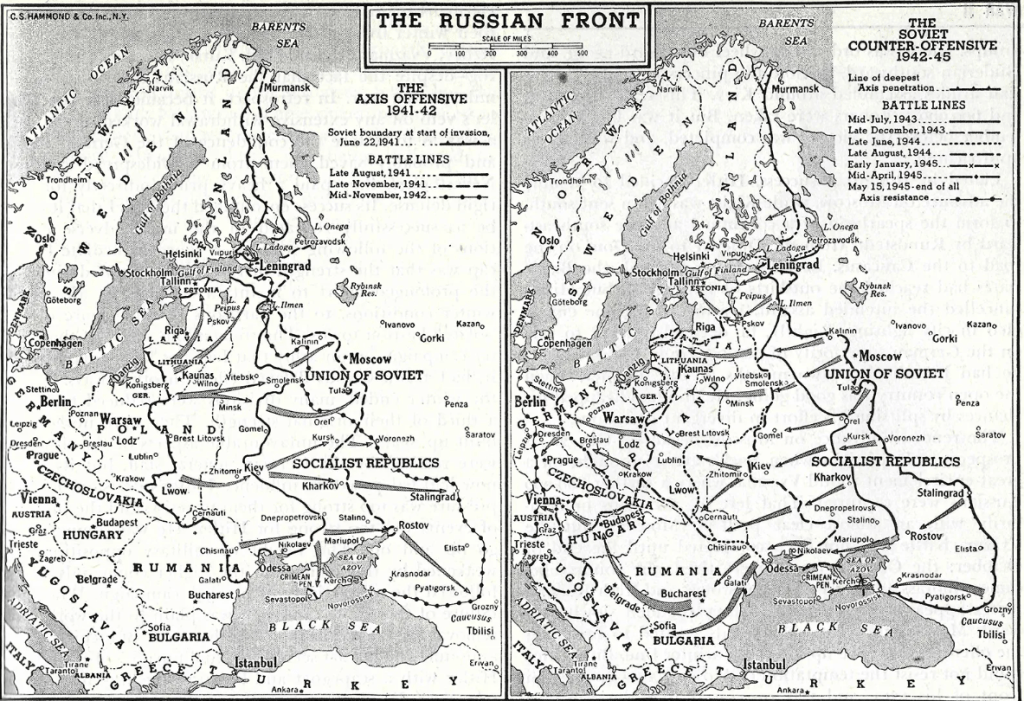

The Soviet-German War 1941–1945 was unprecedented in the scope of its size and scale, covering a vast geographic area and utilizing millions of people, horses, and machines, as well as a huge scale of destruction of population and property.[1] This has posed a challenge to historians to both understand the war and then portray it in print. In the main, whether in English-language, German, or Soviet historiography, the approach has been the same, i.e., to construct a narrative story based around the great battles of Moscow, Stalingrad, Kursk, and Berlin. This methodology has shaped our perception of the war, its nature, and character and in some ways diminished it to a scale that can be comprehended. There have been other approaches over the years, most notably the canon of Soviet strategic operations, offering the basis for another interpretation and that is the objective of this article.

Using an expanded version of the canon of Soviet strategic operations, this article seeks to build an alternative viewpoint of the Soviet-German War as seen through the lens of the Soviet High Command. The first section examines the historiography of the Soviet-German War and where the canon of Soviet operations sits within it, while the second section explores the available dataset, its evolution over time, the problems, and corrections. The final section presents an interpretation of the dataset, using a variety of different parameters and viewpoints identifying what this reveals about the nature of the Soviet-German War. In conclusion, the article discusses the results and examines if these change the view of the war.

Historiography

The earliest attempts by Western historiography, to create a satisfactory narrative of the Soviet-German War were detailed by Rolf-Dieter Müller and Gerd Ueberschär in their 2009 book[2] and included, among others, Alexander Werth, Earl Ziemke, Albert Seaton, John Bellamy, Stephen Fritz, Christian Hartmann, and most recently Evan Mawdsley.[3] To a large extent, they chose to adopt a narrative form in which the war is defined by a series of large battles such as Moscow, Stalingrad, Kursk, and Berlin. The exception of this sequence is the 900-day siege of Leningrad, whose duration spans the first three large battles, and this is treated as an outlier from the main course of events of the war. There have been several exceptions to this trend, particularly John Erickson and David Glantz who have attempted to incorporate a wider range of operations within their narratives.[4]

In large part, a similar narrative style was adopted by German historiography, defining the war as a series of successful Axis ‘summer campaigns’ interspersed by the suffering of Soviet ‘winter counter-offensives’, a form used by both popular writers such as Paul Carell (Paul Karl Schmidt) and in the German official history.[5] It is noteworthy that in the official history, one volume is devoted to the successful six-month campaign of 1941 (volume 4), while the long series of defeats over the two years of 1943-44 is likewise covered by a single volume (volume 8). During the war, the German Army did start a study of the war based on its own series of operations, though the project was captured by the Soviets at the end of the war.[6] In addition to the narrative pressures, German historiography was influenced by the need to create the myth of the ‘clean Wehrmacht’ and to conceal the extent of the brutality of the German occupation of Eastern Europe. The consequence of these pressures resulted in a truncated and twisted history until this viewpoint came under attack from 1979 onward and the exhibition of wartime photographs (Wehrmachtsausstellung) at the Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung in 1995, which shattered the myth.[7]

In large part, the Soviet Union followed the trend of using a narrative approach to the story of the war based on the signposts of the large battles. However, this was less evident, because the Soviet official histories tended to be larger and concentrated solely on the Soviet-German War, whereas the German official histories covered the entirety of the Second World War. With additional space, Soviet historians were able to devote more room to side events away from the main narrative path. Nevertheless, they were heavily influenced by the need to meet political objectives in forming a narrative of the Great Patriotic War, pressures that were as strong as those facing German historians.

The writing of history in the Soviet Union had been a deeply political act ever since the creation of the Short Course in 1938 and political orthodoxy was rigidly enforced by the Party’s Institute for Marxism-Leninism which oversaw the work of the Division of History of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.[8] In the immediate post-war years, this produced a narrative extolling the successes of Stalin and downplaying the roles of senior commanders, yet this changed radically following the death of Stalin and Khrushchev’s secret speech at the XX Party Congress in February 1956. The easing of Party scrutiny in the confusion following the speech, allowed a decade of more revisionist historical debate by the ‘people of the 1960s’ (shesticlesyatniki) made up of those younger historians and soldier/historians (frontoviki) who had returned from the war. This period of debate can be said to have ended in 1967 with the Nekrich Affair and saw many of the revisionist historians banished to obscure corners of academia and even a few to the camps.[9]

It was during this period that the first official history appeared in 1960, the first of four such histories, which reflected the twists and turns of Soviet historical debate throughout the Soviet period and after it.[10] To reinforce the official narrative, Soviet historians created a framework for the war, dividing it into three distinct periods: a period of defeat from 22 June 1941 to 18 November 1942, a period of balance from 19 November 1942 to 31 December 1943, and a period of victory from 1 January 1944 to 9 May 1945.[11]

A key element of the 1960s revision was the enhanced role given to the memoirs of the wartime commanders who by 1956 had wrested control of the armed forces away from the older political marshals and after the ’secret speech’ wrested control of the historical narrative away from the Party historians.[12] This produced a flood of memoirs written by former wartime commanders, which over the years and through numerous editions, gradually revealed much background to the war.[13 ]This was a two-edged sword, as the commanders had reputations to protect and there was a pressure to downgrade the importance of some operations or keep secret ones that had failed or gone badly. For instance, the Uman-Botsani Operation was originally held up as a model operation and the first instance of a tank army successfully performing a ‘deep operation’ that penetrated the German rear. However, the following First Iasi-Kinishev Operation was a failure, besmirching the reputation of Marshal Konev, so the Uman-Botsani Operation was downgraded in importance after the 1960s.[14]

The commanders were aided in their revisionism because the General Staff of the Red Army (Gensthab) was already creating its own military history of the war, shielded from scrutiny by military security. The secret nature of working with the records of the Gensthab allowed the officers of the Military-Historical Department (the Military-Historical Directorate from 1946) to record a distinct, separate historical narrative held within the directorate.[15] The results of this work were published in 1958 with Platonov’s ‘secret’ four-volume work and in 1961 with the publication of the ‘top secret’ ‘Strategic Essay on the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945’.[16] The creation of a canon of operations of the Red Army during the war was a key element in this work as it formed a separate, albeit linked narrative structure for the war.

The ‘canon of operations’ was made up of operations (operat͡sii), grouped into strategic operations (strategicheskie operat͡sii) and ‘battles’ (srazheniye or bitva), and fitted into the standard periods of the war. While the operations might rise and fall in importance, there was a reluctance to eradicate them, especially as many of them had been used in the wartime ‘Experience of War’ studies. Yet such were the high levels of casualties in some failed operations that were downgraded or disappeared entirely from the record.

The story of the war that emerges from these three historiographic traditions is often partial, biased, and less than complete, yet they have converged over time around the key main narrative of the major battles, with much else forgotten or downgraded in importance. Despite this, enough new material has emerged over the years that many biases, such as the myth of the clean Wehrmacht, have been challenged and removed.

Data used in this study

An alternative picture of the war can be gained from the canon of operations provided by the Genshtab. The reason for this is that it portrays the war in small incremental steps that build up into the whole picture. Minor operations appeared in veterans’ memoirs or later revised editions and evaded the military censors or they were published during times of a lifting of restrictions. This canon first appeared in 1953 as a secret study within the Gensthab[17], followed by a book written by Golikov in 1954,[18] another by Zhilin in 1956,[19] and then as the secret edition of Platonov’s four-volume work in 1958,[20] and the top secret ‘Strategic essay on the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945’ in 1961.[21] These works revealed a list of 50 strategic operations covering the four years of the war and it remained without serious challenges until 1985, when it was questioned in an article in Voenno-Istoricheskiĭ Zhurnal (VIZh) by Gurkin and Golovnin.[22] Note the date: shortly after Gorbachev was appointed General Secretary and of course at the time, VIZh was a secret document restricted to military officers.

This article started a debate within the ranks of Soviet officer historians that lasted over two years, with a series of published articles debating both the number of operations within the canon, as well as their relative importance. There were bitter debates over emotive subjects such as the battles at Rzhev, yet by the end of the debate in October 1987, the total of strategic operations had been increased by just one. In 1993, General Krivosheev published the results of his study on Soviet casualty numbers and used a 50 strategic operation canon as his structure, with Table 75 listing an additional 43 smaller operations.[23] By this point in time, the Soviet Union had collapsed, and debate was freer than before with questions being raised by such respected senior officers as Makhmut Gareev, president of the Russian Academy of Military Sciences and former battalion commander at the battle of Rzhev.[24] In his 1994 Novaia I Noveishaia Istoriia article, Gareev raised the thorny issue of the ‘hidden’ failed offensives and in effect demanded that they be remembered.

Despite this, the English language 1997 edition of Krivosheev’s book still used the 50/43 operation structure, though the 2001 edition of his new book changed to using a 50 strategic operations structure with a new Table 142 that listed 73 smaller operations.[25] This list was different from the one in the former editions and between them, Krivosheev acknowledged the existence of 83 operations. He indicated that there were officially 50 strategic operations, 250 front operations, and over 1,000 army-initiated operations. The 2009/2010 editions raised the number of strategic operations to 51 to match the VIZh total and kept the 73 operations in Table 35.[26] One has some sympathy for Krivosheev since the principal aim of his team’s study was to calculate and assign Soviet casualty figures and he was rapidly being overtaken by events.

As a matter of fact, in 2001 Fes’kov wrote a book that listed no less than 75 strategic operations and 223 operations, although the main focus of the book was to provide information on the units of the Red Army and their combat paths from front to regiment level.[27] A simple cross-check of the operations listed in Krivosheev (both the 43 and 73 versions) and Fes’kov shows that they do not correspond and that there are 54 additional operations listed in Krivosheev that are not listed in Fe’skov. This would bring the total number of operations to 277, which remains the current total revealed by Soviet/Russian historians.

There was some criticism about this evolution of the Soviet operational canon from David Glantz, who in 1995 penned an article on what he called the ‘forgotten battles’ of the Soviet-German War.[28] He observed that as many as one-third of the operations might be missing from the Soviet canon, for a combination of reasons relating to both Soviet and German historiography. He went on to give case studies on these ‘forgotten battles’ in a series of articles published in this journal between 1999 and 2001.[29] He expanded on this theme with an eight-volume work (six volumes published to date) that detailed the missing operations of the day, although some of these did appear in Fe’skov’s book of 2001.[30] While the last two volumes remain unpublished to date, the material was used in the revised edition of When Titans Clashed[31,] albeit in outline.[32]

Now there exists a published canon of Soviet operations to which can be added further operations from Krivosheev’s books, and the additional ones from Glantz’s critique. To this can be added some further insight on particular operations from individual studies, in particular the historian and museum curator in Tver, Svetlana Gerasimonva’s study of the Rzhev battles in which she discusses whether this series of operations constitutes an individual strategic operation or an extension of the Moscow Strategic Operation (Moskovskai͡a nastupatelʹnai͡a operat͡sii͡a 05.12.1941-07.01.1942).[33]

This study uses a combination of the Fes’kov list to which have been added the operations as detailed in Glantz’s ‘forgotten battles’ series of books and articles, plus additional operations mentioned in the revised edition of When Titans Clashed.[34] This gives a total of 95 strategic operations and 325 front operations for the 1,418 days of the war. It was decided not to use the 54 additional operations that appear in Krivosheev (and not in Fes’kov) because 18 appear in Glantz and it was unclear whether the others were ‘missing’ operations or simply ones that Krivosheev had renamed. In other cases, Krivosheev had aggregated operations into groups to present his data. Given the uncertainty surrounding his methodology, it was considered best not to include these 36 operations, but to note their existence in case further clarification became available later.

The dataset presents several problems which need to be understood when using it. In the first place neither a strategic operation nor an operation has a fixed size in terms of the number of troops involved, the geographic scope nor the time elapsed. One of the smallest operations was the Defence of Odessa in August 1941 involving just 34,500 personnel while by contrast, the Lower Silesian Offensive Operation in February 1945 involved 980,000. Similarly, the Demiansk Offensive Operation in September 1942 lasted just one day, while the longest, the Defense of Sevastopol, lasted 247 days which was an outlier, since the next longest measured 133 which was the Demiansk Offensive Operation of January to May 1942. This has implications in viewing the dataset strictly from a statistical viewpoint, as a subjective assessment needs to be made alongside it. For instance, Q4 1942 appears to be quite a quiet period with only 7 operations. However, this period includes Operation Mars and Operation Uranus, both of which were huge operations involving over a million men each.

The second issue is the definitions used to describe the different levels of operations by Soviet historians, i.e., the terms strategic operation (strategicheskie operat͡sii), operation (operat͡sii), and battle (bitva).[35] While these were supposed to link individual operations into a more cohesive whole, in reality, the application of the term ‘strategic operation’ was often subjective and was questioned in the VIZh debate of 1985–7. For example, Gerasimova argues that the sequence of the Rzhev operations should be joined into a strategic operation, as they all had a common objective set by Stavka-VGK, and yet they never have been ranked as such.

A further issue is how Soviet historians divide the war into three major periods and eight minor ones to group the operations into broad campaigns. While this gives the narrative of the war a structure, these are all of unequal size and do not fit annual or seasonal variations, all of which make it more difficult to observe patterns or make comparisons. While in some ways useful, a solution is to reformat the dataset into annual quarters.

Background

James Schneider has argued that from 1929 Stalin set out to create a ‘warfare state’ in the Soviet Union, as a country that was continuously preparing to fight a major war.[36] This was reflected in the collectivization of agriculture, the industrial modernization of the Five-Year Plans, and changes in the way the country was governed. These changes, such as the creation of the GKO (State Committee for Defense), ran alongside the work of military theorists in developing a particularly Soviet doctrine of warfighting at the strategic and operational levels. These two strands were fused by the work of Boris Mikhaylovich Shaposhnikov, in forming a national command structure to bring together civilian and governmental bodies, as well as the military.[37] This section discusses how this command structure worked in practice and what it delivered in terms of military activity.

The Soviet doctrine of fighting a war had evolved through the work of Soviet military thinkers such as A.A. Svechin, V.K. Trindafilov, M.N. Tukhachevskii, and, most importantly, G.S. Isserson, who conceived the concept of ‘operational art’ (operativnoe iskusstvo).[38] Although the conflict between Tukhachevskii and Voroshilov discredited this doctrine during the purge of the Red Army in 1937–8, by December 1940 the concepts were being rehabilitated by Timoshenko at a conference.[39] The doctrine envisaged:

The impossibility on a modern wide front of destroying the enemy army by one blow forces the achievement of that aim by a series of successive operations.[40] and: “It is essential to conduct a series of successive operations which are appropriately distributed in space and time. By a combination of a series of operations, it is essential to force the enemy to exhaust its material and human resources or cause the enemy to accept battle by the main mass of troops under disadvantageous conditions and eliminate them”.[41]

This doctrine was carried out using the twin concepts of ‘deep battle’ (1929) and ‘deep operations’ (1936), which: “consisted of simultaneous attacks on the enemy defense with all means of attack to the entire depth of the defense; a penetration of the tactical defense zone on selected directions and subsequent decisive development of tactical success into operational success by means of introducing into battle an echelon to develop success (tanks, motorized infantry, cavalry) and the landing of air assaults to achieve rapidly the desired aim”.[42]

A modern deep breakthrough essentially requires two operational assault echelons: an attack echelon for breaking a front tactically; and a breakthrough echelon for inflicting a depth-to-depth blow to shatter and crush enemy resistance through the entire operational depth.[43]

By 1937, these concepts were starting to be put into practice. However, there had been little time or imperatives to address the issue of logistics. Triandafillov envisaged that consecutive front operations would cover 15 km a day and be reliant on the reconstruction rate of railways, taking a month to cover 250 km.[44] It was recognized that modern armies were deployed in deep echelons covering large distances and Isserson envisaged this spread over 60 to 100 km, so the attacking army would need combat support by the rear for an extended distance and period.[45] The interwar Red Army suffered from a poor transport network, inadequate logistical support, and a lack of understanding among command echelons.[46]

These Soviet concepts translated during the war into the practical arrangement of the military forces, the command structure, and the command cycle. For instance, on 1 January 1944, the 6,390,046 personnel of the operational army were spread over 3,500 km of the frontline.[47] They were organized into 55 ‘combined-arms armies’ (obshchevoĭskovaia armiia) and 3 ‘tank armies’ (tankovaia armiia) of 50 to 80,000 men each holding 60 km of the frontline. Around five ‘combined-arms armies’ were grouped into an ‘army group’ (front) and there were 12 of these ‘fronts’ along four ‘strategic directions’.[48] The first way to gain sufficient concentrations of men and material for a defensive operation or to launch an offensive was for fronts to shuffle around the armies in their sector to produce the required concentrations.

The second way in which these concentrations were created was by filling out the usually depleted units with replacement soldiers and weapons, and the third method was reinforcement by Stavka-VGK, which meant deploying additional armies and specialized units from the Stavka-VGK strategic reserve (RVGK), which in 1944 contained 533,110 personnel in six combined-arms and two tank armies.[49] Transport capacity was a limiting factor in this scheme, so most replacements and RVGK units came from the interior by railway, and there were relatively few transfers of units along the front line. In terms of spatial arrangement of forces, during the war, an army might have a depth of 100 km, while a front might be deployed over 250 km with several echelons of forces and an array of rear institutions spread across the entire depth.[50]

The genesis of an operation was a discussion instigated by Stalin with the other members of Stavka-VGK (officers) and members of the GKO (civilians), NKO (officers/civilians), or Genshtab (officers) on specific topics who were called into Stalin’s office by Poskrebyshev, his factotum.[51] Stalin tended to arrive in the office during the afternoon and worked through to the early hours, often continuing discussions in his Kremlin apartment or dacha outside Moscow.[52] He would summon people into his office or call them on the scrambled HF (VCh) telephone system, his connection to the fronts, and Stavka-VGK representatives in the field.[53] For conversations by teleprinter Stalin would use the one in Poskrebyshev’s office or if he needed radio communication, Stalin would walk the 100 m down the street to the office of the Genshtab.[54]

These discussions produced a Stavka-VGK directive which was sent to the front commander to create a detailed operational plan with his staff.[55] The planning process would be overseen by the Genshtab in Moscow offering advice, information, and supervision.[56] Major multi-front operations would be coordinated and overseen by a Stavka-VGK representative on the ground and for some such as Operation Bagration, a conference might be convened in Stalin’s office between all the major participants.[57] The front commander and his staff had around 10–15 days to produce a detailed plan of the operation for approval by the Genshtab and Stavka-VGK. Once agreed, a period of around 10 days was allowed for the necessary troops to move into position and for the supplies to be delivered to the units, after which the offensive was launched and carried out over the next 15 days.[58]

Within this scheme ‘strategic directions’ were important, as they defined the main axes of advance, and during 1941–42, they were assigned an actual headquarters, led by a civilian member of the GKO.[59] These were in 1941–42: North-western, Western, South-western Directions, 1942: North Caucasian Direction, 1945: Far Eastern Direction. In 1941, Stavka-VGK experienced great difficulty in communicating with the front commanders, who were often cut off by poor communications, which explains the need for this extra level of command. As communications with Moscow improved during 1942, these strategic direction headquarters were found to be unnecessary, and their function was largely replaced by the Stavka-VGK representatives.[60]

A parallel planning process ran alongside this between the Chief of the Rear, the Staff of the Rear, and the Deputy Commander of the Front/Army (Rear Commander), which during the planning stage determined what stocks were held by the relevant front/army and then during the build-up phase arranged delivery of the necessary supplies to fulfill the planned allocation.[61] Central control was quite detailed and specified which railway lines were to support each front, which stations were to act as regulating stations, and a Centre Base NKO allocated to support them.[62] Although a separate command channel, it required the Chief of the Rear, Rear Staff, and Deputy Commander Front to be fully involved in all aspects of the operational planning. In the third period of the war, rear operational teams were sent out from Moscow to help deal with coordination and overcome specific problems.[63]

This ‘top-down’ command cycle could fail if Stavka-VGK did not make the right decisions, especially in the early years of the war when its ‘ambition’ exceeded the capabilities of the army to deliver.[64] The challenge facing historians is how to quantify Stavka-VGK’s ‘ambition’ and this is one area that is particularly suited to the analysis of the Soviet canon of operations.

The combination of the doctrine of warfighting developed during the 1930s, the centralized command structure, and the tempo of operations all demonstrate that the Soviet Union had established a fixed idea about the means of both fighting and winning a large land war in Europe. While this was subject to a process of evolution throughout the war, the basic structure remained the same, the problem it posed was maintaining the high tempo of warfare, as this was an expensive way of fighting and one that stretched the resources of the Soviet Union to the limit.

Similarly, how the war was fought meant that the Chief of the Rear was faced with a continual churn of operations along as many as four strategic directions simultaneously, even if the activity of individual fronts varied considerably within each direction. Moreover, each operation was supported for a relatively short period, on average for 10 days during the build-up out of a 30–40-day cycle, with 10–15 days of planning and 10–15 days of active operations. While it is true that all fronts received some level of support even if they were not conducting operations, this was quite limited, especially given the fact that the Red Army drew 50% of its food requirement from the local area, through the local Party administration.[65]

Interpretation

The scope of the German-Soviet War as portrayed by Fes’kov shows 72 strategic operations and 175 operations, plus 13 strategic operations which are counted as individual operations, while adding the ‘missing’ operations from Glantz increases this number to 95 strategic operations and 325 operations.[66] There is little doubt that this is not a complete listing of the Soviet canon of operations. Further ‘forgotten battles’ are waiting to be found and work remains to be done on reordering the importance of specific operations.

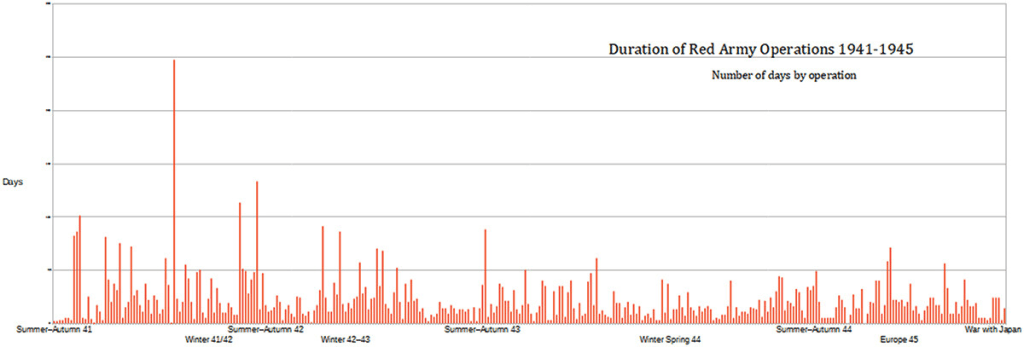

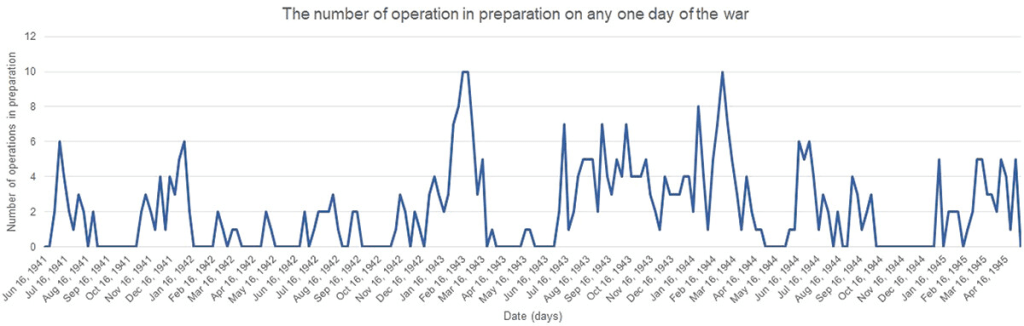

In terms of duration, the war was 1,418 calendar days long divided into 17 Quarters (Q2 1941 was 8 calendar days and Q2 1945 was 39 calendar days long,) and was divided into 325 operations which totaled 7,153 ‘operational days’ (these are the sum total of the duration of individual operations in days). This indicates that there were on average five operations taking place simultaneously every calendar day of the war. The overall pattern is shown in Figure 1 as the duration of all 325 operations.

Figure 1. Duration of operations 1941–1945 shown over time.

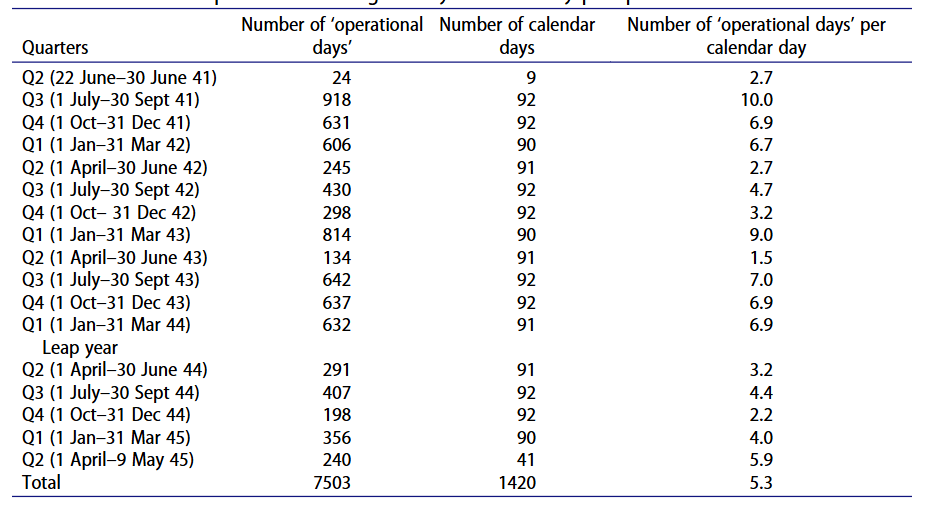

There is a distinct pattern with longer duration operations concentrated between the start of the war and the winter of 1942–43 and only four from that point onward until the end of the war. The level of activity is shown every quarter in Table 1.

Table 1. Number of operations running on any calendar day per quarter.

The quarterly series reveals a definite pattern within war, Q2 was always a quiet period for every year and there were two periods of relative inactivity, Q2 of 1943 and Q4 of 1944 when there were operational pauses for both the Soviets and Axis. The opening of the war from Q3 1941 to Q1 1942 was a period of high activity with between 6 and 10 operations running daily. The defensive battles of 1942, Q3-Q4 ran between 3 and 5 operations a calendar day, yet ramped up to 9 operations a calendar day for the winter counter-attack in Q1 1943. The defensive battles of 1943 and the following counter-attack Q3 1943–Q1 1944 ran at 7 operations a calendar day, followed by a pause. For the rest of 1944 to the end of the war, 4–5 operations a calendar day was more the norm. The same broad pattern is repeated when looking at the duration of strategic operations, as shown in Figure 2

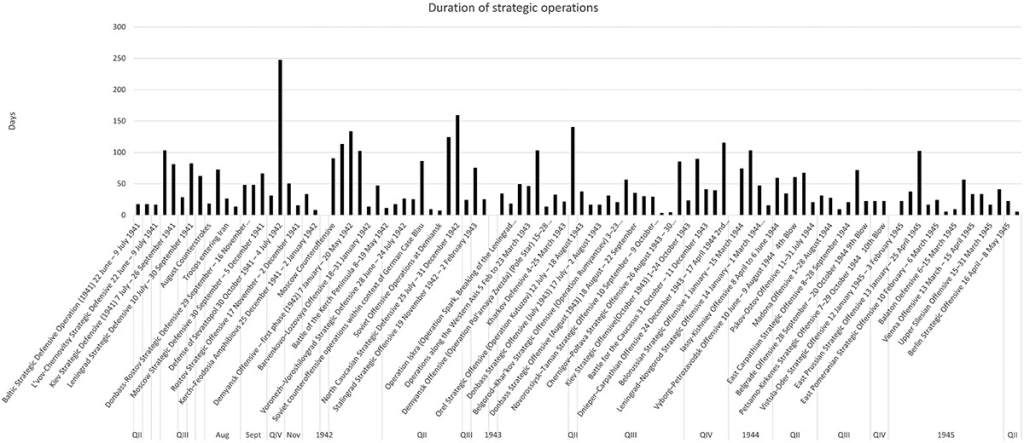

Figure 2 Duration of strategic operations shown over time

There were on average 6.7 strategic operations per quarter spread across three to four strategic directions, comprising 19 operations lasting on average 22 calendar days and involving 1.2 Fronts per operation. The shortest operation was 1 calendar day and the longest was the siege of Sevastopol lasting 247 calendar days. To illustrate this, Figure 3 shows the number of operations in any given quarter and the average number of days of those operations.

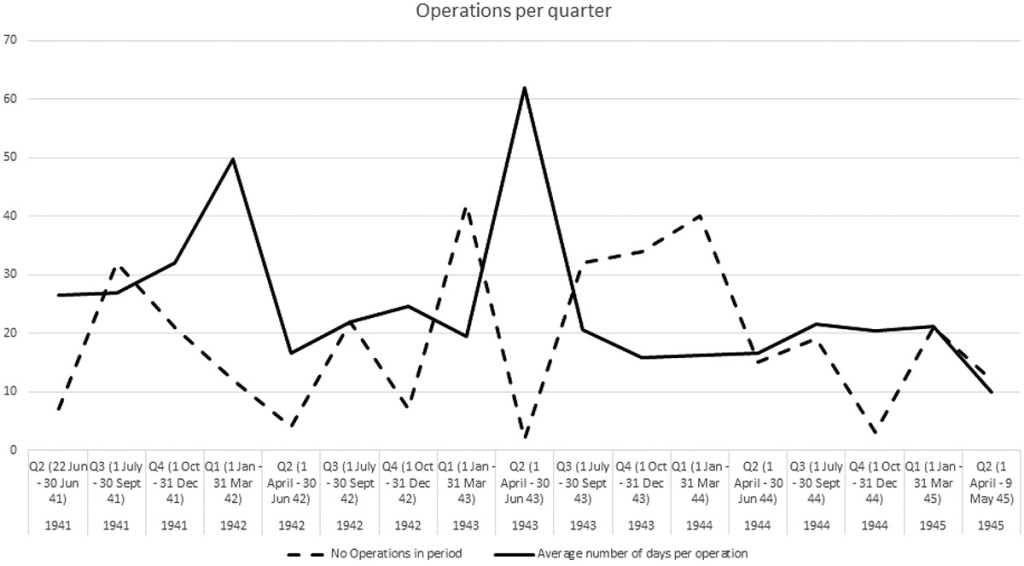

Figure 3 Number of operations per quarter and the average number of calendar days per operation

This shows that most quarters had around 20 operations (dotted line) with a higher rate of 30 operations for Q3 1943–Q1 1944, which was the period of major Soviet offensives after the battle of Kursk. There are four quarters with low activity, Q2 1942, Q4 1942, Q2 1943, and Q4 1944. Two of these contain major operations, Q2 1942: Battle of Kharkov and Voronezh–Voroshilovgrad Strategic Defense and Q4 1942 Operations Uranus and Mars, all of which involved forces numbering millions of men. Q2 1943 and Q4 1944 were both genuinely quiet operational pauses. The average number of calendar days for an operation (solid line) was typically around 20 days, with a slightly higher rate in 1941 and peaks of activity in Q1 1942 and Q2 1943. It is noticeable that these peaks coincided with quarters with low numbers of operations.

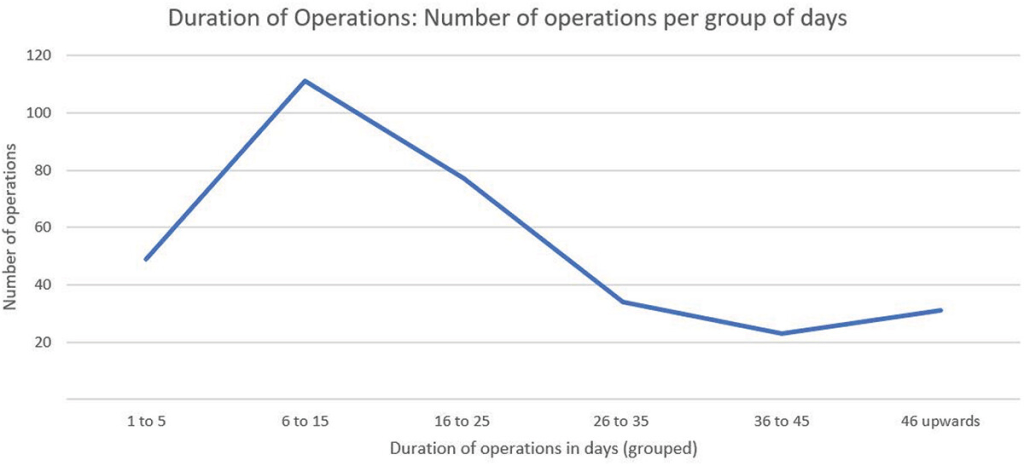

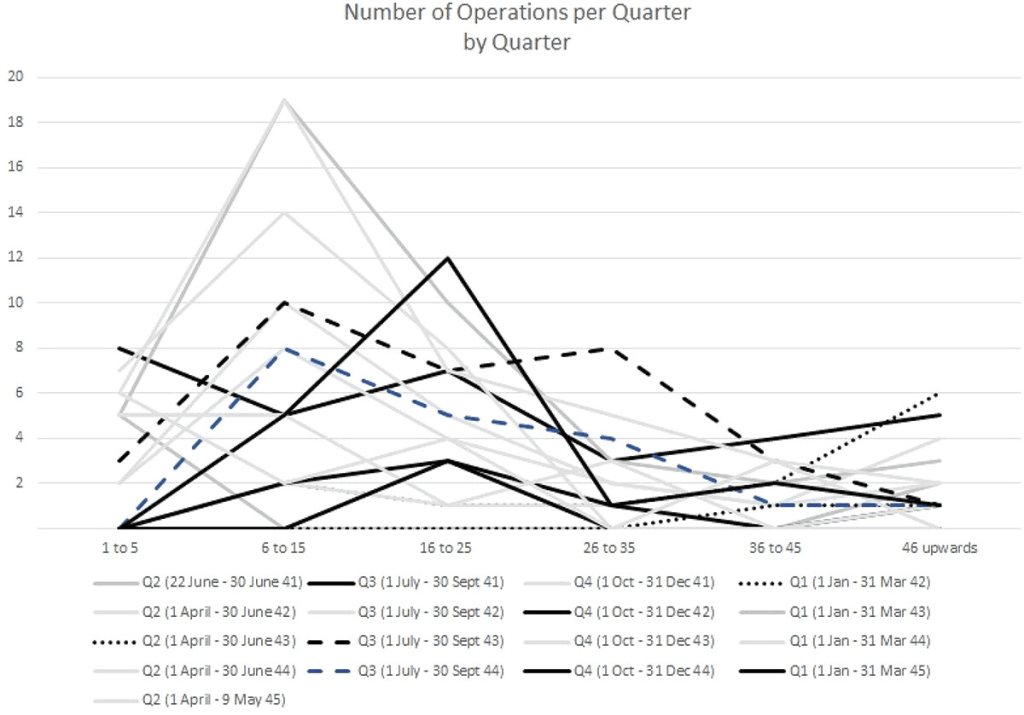

Having looked at the number of operations, the next item to consider is the duration of operations which is shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4. Duration of operations during the war.

Figure 5. Duration of operations by quarter.

Figure 4 shows the average duration of operations during the war, which illustrates that most operations were 6–15 calendar days long, with a substantial number of 16–25 days long and fewer numbers at 1– 5 days or more than 26 days. Operations with a length of 1-5 calendar days represented 15% of the total, those with a length of 6–15 days 34%, and those with a length of 16–25 days 24%, while those longer than 26 days were 27%. This is in line with Soviet military thinking that aimed for a typical operation to last 15 calendar days.

Looking at the same data every quarter shows a similar pattern. There are four quarters where the most common operation length is 1–5 calendar days (solid grey lines), 10 quarters where it is 6–15 days, 3 quarters where it is 16–25 days (solid black line), and only 2 quarters where the most common length is over 25 days. Two quarters have secondary peaks (dashed line.) Again, it shows that the typical length of an operation was 6–15 calendar days duration, even if there was still quite a spread in duration for most quarters. For instance, one of the busiest quarters was Q1 of 1944 which had 40 operations, 1–5 days 6, 6–15 days 19, 16–25 days 7, 26–35 days 5, 35–45 days 3, so hard as Stavka-VGK tried, some operations just dragged on. While duration is an important element in our understanding, the key element in recasting the narrative forms of the war is geographic distribution.

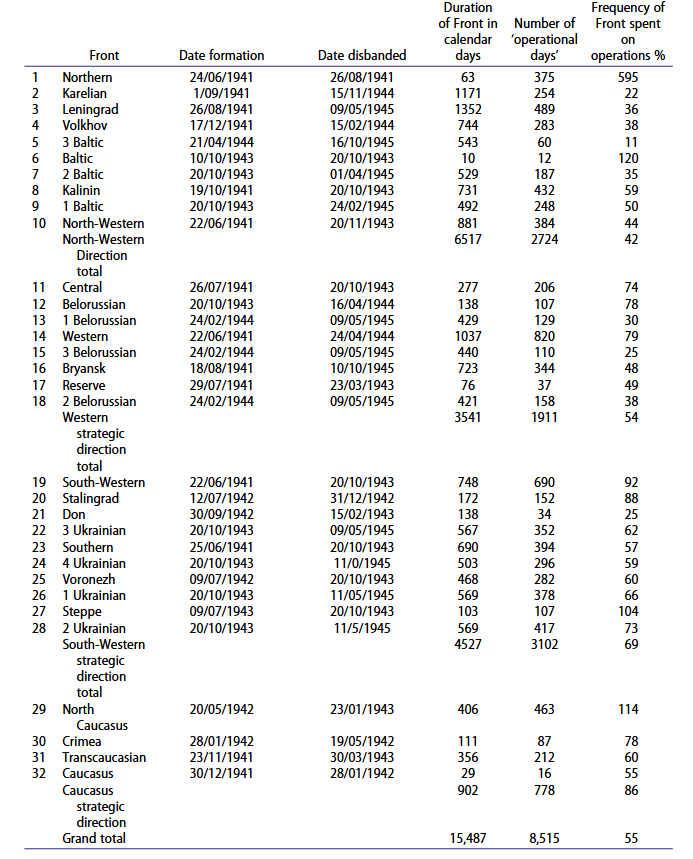

The geographic distribution of operations can be studied from the front and strategic direction viewpoints.[67] At the front level, it is possible to analyze the frequency with which individual fronts conducted operations. This information is given in Table 2, which shows how many days a front devoted to operations throughout its existence and to group the fronts into strategic directions.[68]

Table 2. Proportion of front existence spent on operations.

This table shows the number of calendar days that a front existed and how many ‘operational days’ it spent conducting operations and from this, it calculates the frequency of operations. For example, as can be seen from line 1, Northern Front existed for just 63 calendar days and was involved in operations that totaled 375 operational days. This results in a frequency of 595%, which means that during its short life in 1941, the front conducted multiple operations simultaneously. An examination of the canon of operations shows that the Northern Front was involved in five operations and by 10 July 1941 these were all running at the same time.

Unsurprisingly, the table shows that the Karelian Front (facing Finland) only conducted operations on 22% of the days of its existence. Most fronts fall into a broad range of between 30% and 60%, with an average of 55%, and it is noteworthy that even ones that appear in narrative accounts to have been involved in continuous operations, such as the 1, 2, 3, and 4 Ukrainian Fronts during 1944, in fact, they were on operations only two-thirds of the time. High frequencies were achieved by the Western Front (1037 days) which was conducting operations 78% of the time, and the South-Western Front (748 days) which was conducting operations 92% of the time.

These two examples highlight an anomaly in the dataset, in that during 1941, the five fronts (Northern, North-Western, Western, South-Western, and Southern,) were very large and conducted multiple operations at the same time. By 1942, fronts were smaller and numbered around twelve, and generally conducted one operation at a time. Given this, it must be borne in mind that the five 1941 fronts have a higher frequency as a result and a few later fronts, such as the Steppe and North Caucasus, show the same feature.

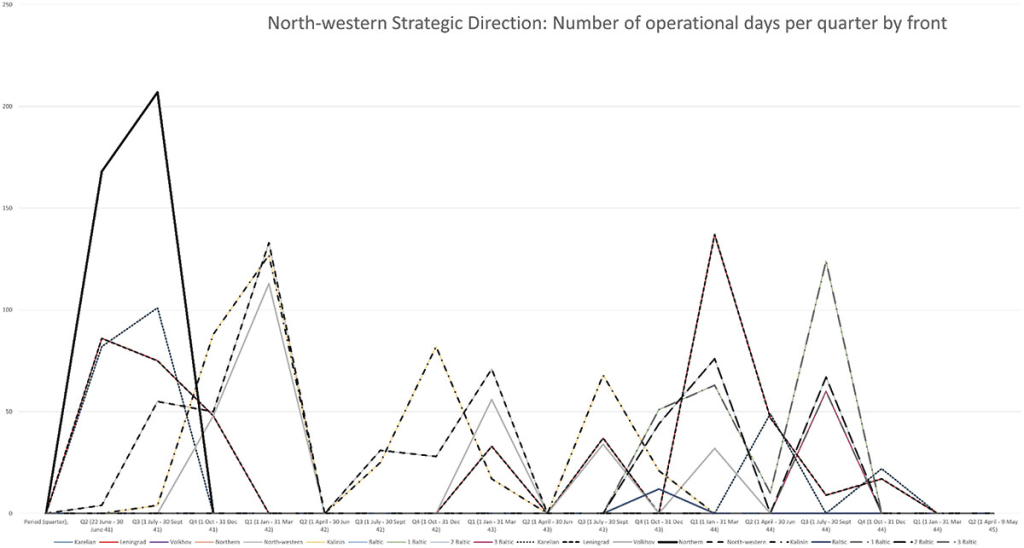

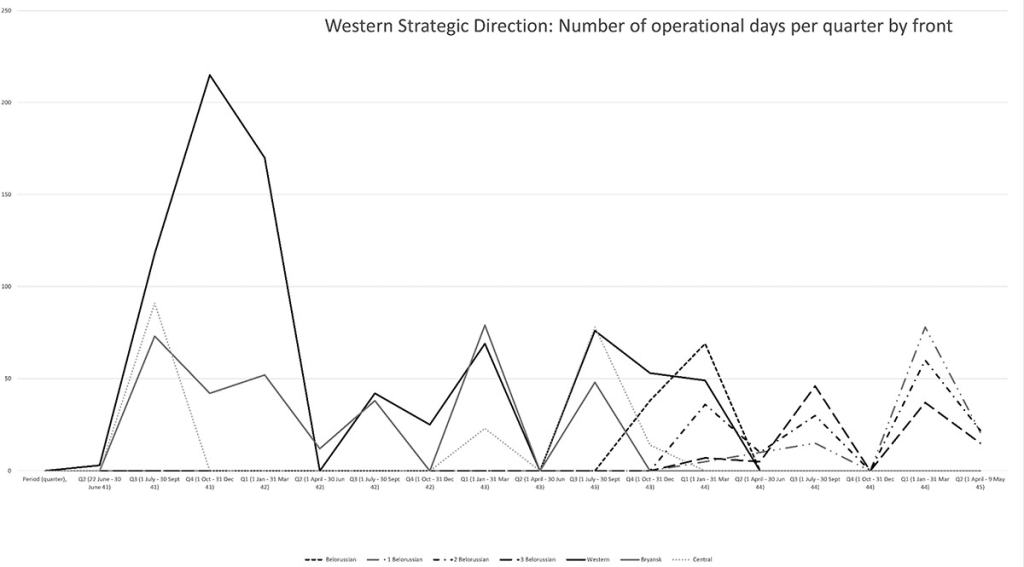

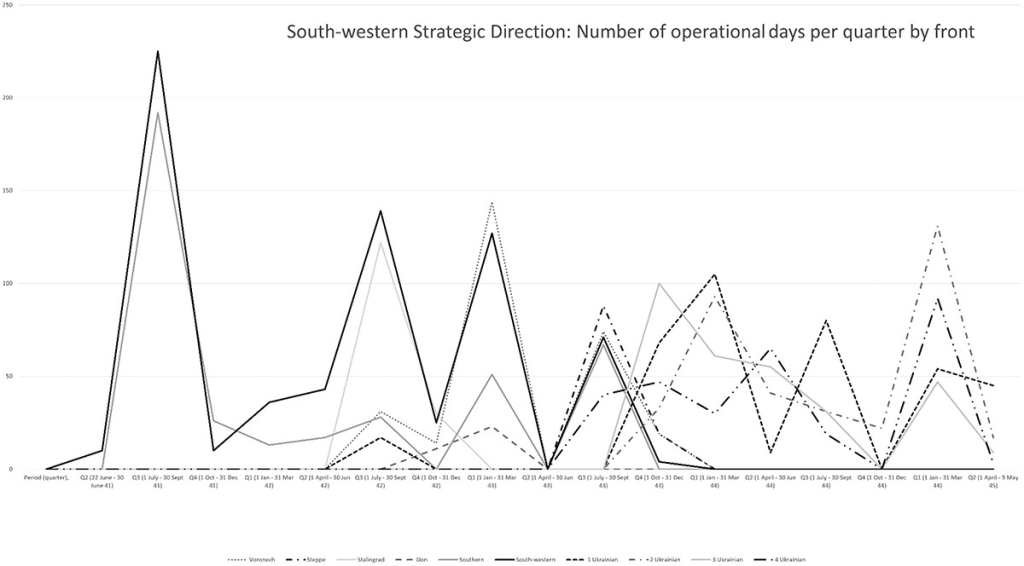

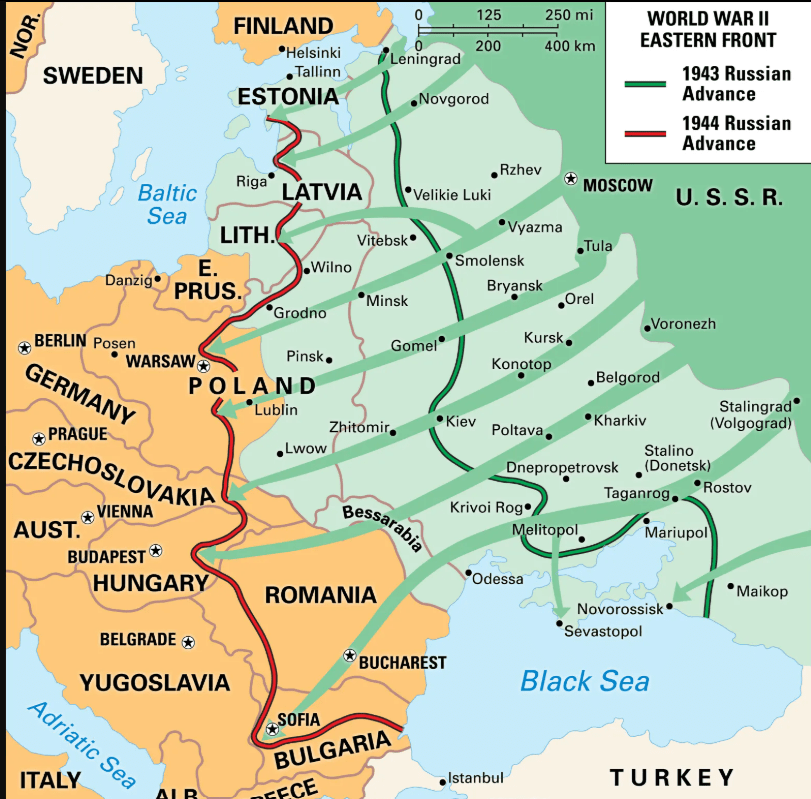

The problem with this method of assessment is that Fronts existed for different lengths of time. For instance, the Northern Front lasted just 63 days from 24 June to 26 August 1941, while the Karelian Front lasted 1171 days from 1 September 1941 to 15 November 1944. Moreover, fronts had a complex evolution with some being formed and disbanded up to three times, merging and splitting. For instance, the South-Western Front became the Stalingrad, then the Don, and finally the 3 Ukrainian Front. However, combining these fronts into the three main strategic directions allows these variations to be overcome as shown in Figures 6–8 below. The series of three graphs plots the number of operational days carried out by each front of the strategic direction for each quarter of the war. When combined, they show the overall activity of each of the three main strategic directions over time.

Figure 6. Front operations by strategic direction: North-Western Strategic Direction.

Figure 7. Front operations by strategic direction: Western Strategic Direction.

Figure 8. Front operations by strategic direction: South-Western Strategic Direction.

These three graphs show that all three main strategic directions were continually active throughout the war, running operations more or less continuously. The South-Western Direction had an overall rate higher than the others. However, they were all active with only short intermissions, demonstrating the broad front approach taken by Stavka-VGK in its direction of war and military operations.

One aspect that this dataset does not address, is the relative weights given to these three strategic directions. Using the number of operational days as a single measure does not reveal how much effort was put into each strategic direction. In a way it does not represent what was planned but rather what was successful. The South-Western Direction might have had a greater number of operations in 1943, simply because it was succeeding and advancing, while the Western strategic direction was held up by a successful defense by the German Army Group Centre and was having to find new ways of breaking through the Axis defenses.

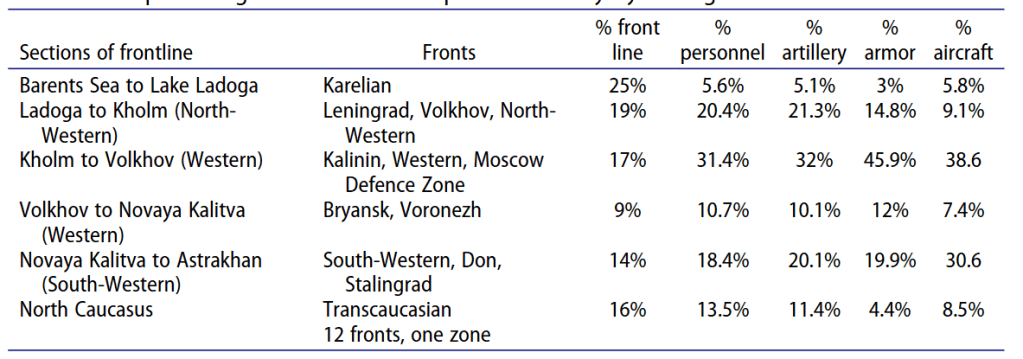

One method to address this issue might be to look at a snapshot of the balance of forces at a specific point in time. The 1973 official history gives a distribution of forces on 19 November 1942, the turning point in the war according to Soviet historiography, and this is shown in Table 3[69].

Table 3. The percentage of forces in the operational army by strategic direction.

The salient features of this snapshot are concentrations of troops relative to the length of the front held, with the Karelian Front holding a quarter of the front with a handful of troops, because this was a geographically challenging area, difficult country to conduct operations in and so relatively quiet. The North-Western strategic direction held 19% of the front with 20% of the personnel which might be considered an average concentration given the importance of the defense of Leningrad. Yet within a little over a month, it would launch Operation Pole Star, the attempt to relieve the siege of Leningrad. The same might apply to the South-Western strategic direction, which at the time was conducting the Battle of Stalingrad and preparing to launch Operation Uranus, as this shows 14% of the front line held by 18% of the personnel and 30% of the aircraft. The interesting one is the Western strategic direction, which was shortly to conduct Operation Mars, as it holds 17% of the front line with 31% of the personnel, a staggering 46% of the armor, and 38% of the aircraft. One can argue that the Volkhov to Novaya Kalitva section should be included in the Western strategic direction which would make the figures even higher, although not alter the main thrust of the argument. The Western strategic direction was clearly hugely important to the Soviet command, as it defended the approaches to Moscow, and a major effort was launched there. Although, as it turned out, the winter counteroffensive only succeeded in the South-Western strategic direction, and its success is reflected in the narrative history.

In addition to this, what is needed is a measure of the ambition or demand of Stavka-VGK. This can be determined by studying the command cycle of offensives, in that on average 10 days before the start date of an operation, the armies were stocking up on supplies and the previous 10–15 days were spent in planning, beginning with a Stavka-VGK directive. While the dates of some of the directives are known, the start dates of offensive give a much larger dataset, and counting the number of offensives within the previous 10 days before any given date will indicate how many operations Stavka-VGK was planning at any one time.[70] This can be determined by using a Gantt chart and plotting the 10 days before the start date of offensives, which indicates the number being planned on any given date. The results are shown in Figure 9, which shows for most of 1942–43 Stavka-VGK was planning no more than two offensives at once, with a burst of activity following the Stalingrad campaign.

Figure 9. Number of operations in preparation on any given day.

From August 1943 until November 1944, the rate was higher at least 4 offensives rising to 7 with a peak of 10 in March 1944. The pause lasted until January 1945, after which the rate ran at up to 5 offensives. This demonstrates that Stavka-VGK was fully employed, typically planning between two and four future offensives, and managing around five current operations, along three separate strategic directions.

Conclusion

The picture of the Soviet-German War painted by the narrative accounts follows a path from the Battle of Moscow in 1941, to the southern campaign ending in the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942, to Kursk in 1943, and then through Ukraine in 1944 to the Battle of Berlin in 1945. This path is the dominant feature and while more modern accounts will include the Siege of Leningrad and other key events, nonetheless these become secondary, side paths. Moreover, this path follows what turned out to be the important events of the war, few would argue that the Battle of Stalingrad was not significant. This importance does not reflect what was important at the time.

Glantz has argued that in the winter of 1942, Operation Mars was as large and significant as Operation Uranus, and when combined with Operation Pole Star, it’s clear that Stavka-VGK was following a broad front strategy to push the Axis back across the whole front. Two of the three offensives failed, while Operation Uranus succeeded, and earned its place in the history books. In essence, the narrative accounts are a study of success and not of effort and planning.

The canon of Soviet offensives offers the prospect of a different viewpoint, one whose focus is on effort and planning as opposed to success. As mentioned previously, it has its problems: it is solely a Soviet viewpoint, it remains partly incomplete and there are issues surrounding the definition of strategic offensives. It dovetails nicely with the Soviet command system, offers a structured approach to understanding the conflict, and builds its picture up from the foundations, brick by brick. Moreover, it offers the prospect of a complete picture of the war and a starting point for understanding the relative importance of events as they were planned.

The picture that emerges is of a gigantic war, one that was fought up and down its entire length for the duration and one in which the churn of men and material was relentless. There were ebbs and flows in the level of activity, throughout operations were being planned, while others built up their offensive stocks, others fought hard while others were winding down and coming to a halt. This constant churn in operations makes the strategic direction the most valuable viewpoint, as it sits above the front level where the churn is taking place. Individual fronts might have different levels of activity, and groups of fronts working towards a common strategic directive had the commonality of purpose.

This study shows that all three Soviet Strategic Directions were fully engaged throughout the entire period of the war, there was no letup in any of their tempo of operations and the war was prosecuted along the whole length of the front. The war was viewed by the Genshtab historians as a ‘broad front’ war, fully in keeping with Soviet military doctrine. From a front perspective, their level of activity was quite variable, yet at the strategic direction level, one or more of their fronts was always operating on any given day of the war. Many of these operations failed, while another front operation was already being planned to take its place. The focus on the events of the South-Western strategic direction ignores the equal importance given to the Western strategic direction, despite this being a tale of dashed hopes and failed opportunities. Moreover, it sidelines the important battle to relieve Leningrad and recover the Baltic States.

This study can reveal a lot about the tempo of operations. What it cannot do, however, is explore the relative weights of those operations. As discussed earlier, operations varied widely in size and while the dataset includes the number of fronts involved in an operation, it does not tell us their size, in terms of numbers of personnel, tanks, guns, and aircraft. This study has not been attempted to collect this data, but it may be the subject of some future study.

A further important point is the sheer level of churn at the Stavka-VGK level and for the Chief of the Rear. Managing three or four strategic directions, some thousands of miles away from Moscow, was no mean feat and every night Stavka-VGK might be initiating two new operations and monitoring five current ones. Similarly, General Khrulev, Chief of the Rear of the Red Army, would have to meet the demands of the three strategic directions demanding supplies on almost a daily basis. Every few days supplies might have a different front as their final destination, as the fronts cycled through their planning, preparation, and operation phases. These destinations might be separated by up to 1,000 km across the frontage of any given strategic direction.

This raises an important question of resource management. The Soviet Union achieved a high level of mobilization, while at the same time, it had a vast army of six million personnel, some 35 million men and women serving it throughout the war, of whom some 10 million died. The turnover of personnel every year was immense and the story of the Soviet canon of operations goes some way in explaining this, with 325 operations over four years demonstrating the wide scope of the war compared to other theatres of war. Likewise, there was a similar turnover of weapons and munitions, fuel, and food. Did this level of resources match the high rate at which operations were carried out? Given the complexity of the war, with numerous operations being carried out simultaneously, how was this controlled? These questions demand further research and investigation and will be examined in a future study

Note:

1 This article covers the main period of Red Army operations during the Soviet-German War (22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945) and excludes the much smaller number of Soviet operations, such as the Occupation of Poland in 1939, the Winter War in 1940, and the Manchurian Operation in August 1945.

2 Rolf-Dieter Müller and Gerd R. Ueberschär, Hitler’s War in the East, 1941-1945: A Critical Assessment, 3rd rev. and expanded ed, War and Genocide (New York: Berghahn Books 2009), pt. B: The Military Campaign (Gerd Ueberschär).

3 Alexander Werth, Russia at War,1941–1945, First Printing edition (London: Barries & Rockcliff (Barrie Books Ltd) 1964); Earl F. Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin: The German Defeat in the East, Army Historical Series (Washington, D.C.: Army Center of Military History 1966); Albert Seaton, The Russo-German War, 1941-45 (New York: Praeger Publishers 1970); John Erickson, The Road to Stalingrad (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1973); John Erickson, The Road to Berlin (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1985); Chris Bellamy, Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War : A Modern History (London: Pan Books 2009); Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941-1945, 1st ed. (London: Bloomsbury 2017); Christian Hartmann, Operation Barbarossa: Nazi Germany’s War in the East, 1941–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2013); Stephen G. Fritz, Ostkrieg: Hitler’s War of Extermination in the East, 2015.

4 Erickson, The Road to Stalingrad; Erickson, The Road to Berlin; David M. Glantz and Jonathan M. House, When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler, Revised edition (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas 2015).

5 Paul Carell, Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943. (Boston: Little, Brown 1965); Paul Carell, Scorched Earth; Hitler’s War on Russia (London: G.G. Harrap 1969); Karl-Heinz Frieser, Manfred Messerschmidt, and Rolf-Dieter Müller, eds., Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg. Band 1-10 [The German Empire and the Second World War. Volumes 1-10], 10 (13 books) vols, Beiträge zur Militär- und Kriegsgeschichte (Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1979–2008).

6 ‘Akte 557. OKH: Chronologisches Verzeichnis der Schlacht- und Gefechtsbezeichnungen für die Kämpfe im Ostfeldzug, an der finnischen Front und in Nordafrika bis Februar 1942’ [File 557. OKH: Chronological list of battle and battle names for the battles in the Eastern Campaign, on the Finnish front and in North Africa until February 1942], Deutsch-Russisches Projekt Zur Digitalisierung Deutscher Dokumente in Archiven Der Russischen Föderation, February 1942, https://wwii.germandocsinrussia.org/de/nodes/1355-akte-557-okh-chronologisches-verzeichnis-der-schlacht-und-gefechtsbezeichnungen-f-r-die-k-mpf#page/1/mode/grid/zoom/1; ‘Akte 67. Chronologische Aufstellung der wichtigsten Operationen, Schlachten und Kämpfe an der Ostfront und im Westen. (1941–1944)’ [File 67. Chronological list of the most important operations, battles, and battles on the Eastern Front and in the West. (1941–1944)], Deutsch-Russisches Projekt Zur Digitalisierung Deutscher Dokumente in Archiven Der Russischen Föderation, September 1944, https://wwii.germandocsinrussia.org/de/nodes/889-akte-67-chronologische-aufstellung-der-wichtigsten-operationen-schlachten-und-k-mpfe-an-der-os#page/19/mode/inspect/zoom/7; ‘Akte 559. Chronologisches Verzeichnis der Schlacht- und Gefechtsbezeichnungen für die Kämpfe im Ostfeldzug 22.06.1941 – 07.1944 und in Italien ab 12.05.1944’ [File 559. Chronological list of battle and battle names for the battles in the Eastern Campaign 22.06.1941–07.1944 and in Italy from 12.05.1944.], Deutsch-Russisches Projekt Zur Digitalisierung Deutscher Dokumente in Archiven Der Russischen Föderation, July 1944, https://wwii.germandocsinrussia.org/de/nodes/1357-akte-559-chronologisches-verzeichnis-der-schlacht-und-gefechtsbezeichnungen-f-r-die-k-mpfe-im#page/1/mode/grid/zoom/1.

7 Christian Streit, Keine Kameraden: die Wehrmacht und die sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941-1945 (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt 1980); Norbert Müller and H.-G. Müller, Wehrmacht und Okkupation 1941–1944, (Schriften d. Deutschen Instituts für Militärgeschichte) (Berlin: Dt. Militärverl 1971); Omer Bartov, Hitler’s Army: Soldiers, Nazis, and War in the Third Reich (Oxford: New York: Oxford University Press 1991); Theo J. Schulte, The German Army and Nazi Policies in Occupied Russia, 1941–1945 (Oxford [Oxfordshire], New York: Berg 1989); ‘Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941–1944 [Crimes of the German Wehrmacht: Dimensions of a War of Annihilation 1941–1944]’, Deutsches Historisches Museum – Berlin, 2001, http://www.verbrechen-der-wehrmacht.de/.

8 Roger D. Markwick, Rewriting History in Soviet Russia: The Politics of Revisionist Historiography, 1956–1974 /Roger D. Markwick; Foreword by Donald J. Raleigh. (Basingstoke: Palgrave 2001), pp. 42, 62.

9 A. M. (Aleksandr Moiseevich) Nekrich and Vladimir Petrov, ‘June 22, 1941’: Soviet Historians and the German Invasion (Columbia SC: South Carolina Press 1968), Prologue.

10 Petr Nikolayevich Pospelov et al., eds., Istroriya Velikoi Otechstvennoi voiny Sovetskogo Soyuza 1941–1945. Tom. 6 [History of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945], 6 vols (Moskva: Voenizdat, 1960), https://prussia.online/books/istoriya-velikoy-otechestvennoy-voyni-sovetskogo-souza-1941-1945-1-6?ysclid=ljg6zpqbg2892936976; A. A. Grechko, G.A. Arbatov, and V.A. Vinogradov, Istorii͡a Vtoroĭ Mirovoĭ Voĭny 1939–1945 [HIstory of the Second World War 1939–1945], 12 vols (Moskva: Voenizdat, 1973–1976); V. A Zolotarev and Institut voennoĭ istorii, Velikai͡a Otechestvennai͡a voĭna, 1941–1945: voenno-istoricheskie ocherki : v chetyrekh knigakh [Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945: military-historical essays: in four books], 4 vols (Moskva: Nauka, 1998); A.Ė. Serdi͡ukov and V.A. Zolotarev, Velikai͡a Otechestvennai͡a voĭna 1941–1945 godov : v dvenadt͡sati tomakh [The Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 in 12 volumes], 12 vols (Moskva: Voennoe Izd-vo, 2015), http://encyclopedia.mil.ru/encyclopedia/books/vov.htm.

11 A. Ė. Serdiukov and V. A. Zolotarev, Velikai͡a Otechestvennai͡a Voĭna 1941–1945 Godov: V Dvenadt͡sati Tomakh [The Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 in 12 Volumes] (Moskva: Voennoe Izd-vo 2011) p. 8.

12 Nekrich and Petrov, ‘June 22, 1941’: Soviet Historians and the German Invasion, p. 10–13.

13 Seweryn Bialer, Stalin and His Generals Soviet Military Memoirs of World War Ii. (Boulder, CO: Western Publishing Company Inc 1969), p. 26–7 as an illustration of the clashes produced by this memoir writing, https://archive.org/details/stalinhisgeneral0000bial/page/n7/mode/2up.

14 David M. Glantz, Red Storm Over the Balkans: The Failed Soviet Invasion of Romania (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas 2007), p. 14.

15 S.L Chekunov, Pishu Iskli͡uchitelʹno Po Pami͡ati … Komandiry Krasnoĭ Armii O Katastrofe Pervykh Dneĭ Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ Voĭny. v 2 T. Tom 1 [I Write Exclusively from Memory … Commanders of the Red Army About the Catastrophe of the First Days of the Great Patriotic War], vol. 1 (Moskva: Russkiĭ Fond Sodeĭstvii͡a Obrazovanii͡u i Nauke, 2017), p. 6–12.

16 S.P. Planonov, Operat͡sii Sovetskikh Vooruzhennykh sil v Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ voĭne 1941–1945 gg. (Voenno-istoricheskiĭ ocherk): V 4 tomakh [Operations of the Soviet Armed Forces in the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945. (Military history sketch): In 4 volumes.], 4 vols (Moskva: Voenizdat 1958), http://prussia.online/books/operatsii-sovetskih-vooruzhennih-sil-v-velikoy-otechestvennoy-voyne-1941-1945-v-4-tomah-4-papki-so-shemami; Voenno-istoricheskiĭ otdel Generalʹnogo Shtaba, Strategicheskiĭ Ocherk Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ 1941-1945 gg. [Strategic essay on the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (Moskva: Voenizdat,1961), https://vk.com/wall-45188300_1921?ysclid=ljg6i5bsip701554975.

17 Perechenʹ osnovnykh operat͡siĭ Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ voĭny Sovetskogo Soi͡uza 1941–1945 gg. [List of the operations of the GPW and the troops of the Soviet Union 1941-1945] (Moskva: General Staff 1953).

18 S.Z. Golikov, Vydai͡ushchiesi͡a pobedy Sovetskoĭ Armii v Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ voĭne [Outstanding Victories of the Soviet Army in the Great Patriotic War. Second revised and enlarged edition], 1954, http://prussia.online/books/vidaushchiesya-pobedi-sovetskoy-armii-v-velikoy-otechestvennoy-voyne.

19 Pavel Andreevich Zhilin, Vazhneĭshie operat͡s ii Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ voĭny 1941–1945 gg.: sbornik stateĭ. [Important operations of the great Patriotic War 1941–1945: Collection of articles] (Moskva: Voen. izd-vo, 1956), http://prussia.online/books/vazhneyshie-operatsii-velikoy-otechestvennoy-voyni-1941-1945-gg.

20 Planonov, Operat͡sii Sovetskikh Vooruzhennykh sil v Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ voĭne 1941–1945 gg. (Voenno-istoricheskiĭ ocherk): V 4 tomakh.

21 Voenno-istoricheskiĭ otdel Generalʹnogo Shtaba, Strategicheskiĭ Ocherk Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ 1941–1945 gg.

22 V.V. Gurkin and M.I. Golovnin, ‘K Voprosu O Strategicheskikh Operat͡sii͡akh Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ Voĭny 1941–1945 Gg.’ [On the Questions of Strategic Operations in the Great Patriotic War], Voenno-Istoricheskiĭ Zhurnal [Military History Journal], On the Questions of Strategic Operations in the Great Patriotic War, no. 10 (1985): 10–23 (English translation JPRS-Foreign Broadcast Information Service pp. 9–24).

23 G.F. Krivosheev, Grif Skretnosti Sniat: Poteri Vooruzhennykh Sil Sssr v Voinakh, Boevykh Deistviiakh I Voennykh Konflikakh [The Secret Classification Removed: The Losses of the Armed Forces of Ussr in Wars, Military Actions and Military Conflicts], 1st ed. (Moskva: Voenizdat, 1993), pp. 162–224, http://prussia.online/books/grif-sekretnosti-snyat.

24 M. Gareev, ‘O neudachnykh nastpatel’nykh operatsiiakh Sovetskikh voisk v Veliokoi Otechstvennoi voine’ [Concerning unsuccessful offensive operations of Soviet forces in the Great Patriotic War], Novaia I Noveishaia Istoriia, January 1994, https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/publication/572.

25 G.F. Krivosheev, Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century (London: Greenhill Books, 1997); G.F. Krivosheev, Rossii͡a i SSSR v voĭnakh XX veka: Poteri vooruzhennykh sil [Russia and USSR in wars of twentieth century: statistical study] (Moscow: OLMA-Press, 2001), pp.108–27, http://lib.ru/MEMUARY/1939-1945/KRIWOSHEEW/poteri.txt.

26 G.F. Krivosheev, Velikai͡a Orechestvennai͡a Bez Rpifa Sekretnosti. Kvira Poterʹ. [The Great Patriotic War Without a Stamp of Secrecy. Book of Losses] (Moskva: Veche, 2009), pp. 75–184, https://www.rulit.me/author/krivosheev-g-f/velikaya-otechestvennaya-bez-grifa-sekretnosti-kniga-poter-novejshee-spravochnoe-izdanie-download-309109.html.

27 V. I Fesʹkov, K. A Kalashnikov, and V. I Golikov, Krasnai͡a Armii͡a v pobedakh i porazhenii͡akh, 1941–1945 gg. [The Red Army in the Victories and Defeats of 1941–1945] (Томск: Tomskiĭ gos. universitet, 2003), p.24-30, http://militera.lib.ru/h/feskov_vi01/index.html.

28 David M. Glantz, ‘The Failures of Historiography: Forgotten Battles of the German-Soviet War (1941–1945)’, Journal of Slavic Military Studies 8(4), (1995): pp. 768–808, https://doi-org.uea.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/13518049508430217.

29 David M. Glantz, ‘Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–45), Part I’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 12(4) (12 January 1999): pp. 149–97, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518049908430421; David M. Glantz, ‘Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–45), Part II’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 13(1) (3 January 2000): pp. 172–237, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040008430433; David M. Glantz, ‘Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–45), Part 3: The Winter Campaign (5 December 1941–April 1942): The Moscow Counteroffensive’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 13, no. 2 (6 January 2000): pp. 139–85, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040008430444; David M. Glantz, ‘Forgotten Battles of the erman‐Soviet War (1941–45), Part 4: The Winter Campaign (5 December 1941–April 1942): The Demiansk Counteroffensive’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 13(3) (9 January 2000): pp. 145–64, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040008430453; David M. Glantz, ‘Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–45), Part 5: The Winter Campaign (5 December 1941–April 1942): The Leningrad Counteroffensive’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 13(4) (12 January 2000): pp. 127–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040008430463; David M. Glantz, ‘Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–45), Part 6: The Winter Campaign (5 December 1941–April 1942): The Crimean Counteroffensive and Reflections’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 14(1) (3 January 2001): pp. 121–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040108430472; David M. Glantz, ‘Forgotten Battles of the German‐Soviet War (1941–45), Part 7: The Summer Campaign (12 May–18 November 1942): Voronezh, July 1942’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 14(3) (9 January 2001): pp. 150–220, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518040108430492.

30 David M. Glantz, Forgotten Battles of the Soviet-German War (1941–1945), I to VIII vols (Carlisle, PA: Self-published 2006).

31 Glantz and House, When Titans Clashed.

32 Confirmed by email from David Glantz

33 Svetlana Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse. The Red Army’s Forgotten 15-Month Campaign against Army Group Center, 1942–1943. (Solihull, West Midlands: Helion & Company 2013), pp.150–6

34 The dataset created for use in this study is made available on the author’s website at https://www.hgwdavie.com/data-appendix. However, it could be re-created from the three sources used.

35 David M. Glantz, Soviet Military Operational Art: In Pursuit of Deep Battle (Frank Cass 1991), chap. 3.

36 James J. Schneider, The Structure of Strategic Revolution: Total War and the Roots of the Soviet Warfare State. (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1994), pp. 1–5.

37 Schneider, pp. 254–7.

38 Schneider, pp. 184–92.

39 Richard W. Harrison, Architect of Soviet Victory in World War II: The Life and Theories of G.S. Isserson (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. 2010), p. 234.

40 Glantz, Soviet Military Operational Art, p. 21.

41 Georgii Samoilovich Isserson, The Evolution of Operational Art, trans. Bruce W. Menning (Fort Leavenworth, KS: US Army, CARL, Combat Studies Institute 2013), p.xvi, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/combat-studies-institute/csi-books/OperationalArt.pdf.

42 David M. Glantz, ‘The Motor-Mechanization Program of the Red Army During the Interwar Years’ (Leavenworth KS, March 1990), p. 15, Defence Technical Information Centre, http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA232707.

43 Isserson, The Evolution of Operational Art, p. 66.

44 Harrison, Architect of Soviet Victory in World War II, p. 148.

45 Isserson, The Evolution of Operational Art, p. 46.

46 Glantz, Soviet Military Operational Art, pp. 56, 61.

47 N. Andronnikov, V. Gnezdilov, and V. Fesenko, Velikai͡a Otechestvennai͡a voĭna 1941–1945. Deĭstvui͡ushchai͡a armii͡a [The Great Patriotic War – The Operational Army], Voennai͡a istorii͡a Gosudarstva Rossiĭskogo v 30 tomakh (Moskva: Kuchkovo Pole: Animi Fortitudo, 2005), p. 560.

48 David M. Glantz, Colossus Reborn: The Red Army at War: 1941–1943 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas 2005), pp. 86, 140.

49 Glantz, pp. 96–100.

50 N.A. Antipenko and N. A Antipenko, ‘Voprosy Tylovono Obespechenii͡a Belort͡ssskoĭ Operat͡sii’ [Questions of Rear Supply in the Belorussian Operation], Voenno-Istoricheskiĭ Zhurnal [Military History Journal] 6 (1964); V.N. Rodin, ed., Razvitie Tyla Sovetskikh Vooruzhennykh Sil, 1918–1988 [The development of the rear of the Soviet Armed Forces (1918-1988)] (Moskva: Voennoe izdatelʹstvo, 1989), pp. 119–20, ; I.M Golushko, Shtab Tyla Krasnoĭ Armii v gody voĭny 1941–1945 [Staff of the Rear of the Red Army 1941–45] (Moskva: Ėkonomika i informatika, 1998), p. 235, .

51 Sheila Fitzpatrick, On Stalin’s Team: The Years of Living Dangerously in Soviet Politics, 2017, p. 162; I͡uriĭ Gorʹkov, Kremlʹ. Stavka. Genshtab. [Kremlin, Stavka, General Staff] (Tver: RIF 1995), p. 138, https://www.e-reading.life/book.php?book=99577.

52 Glantz, Colossus Reborn, pp. 91–6; N.D. Yakovlev, Ob Artillerii I Nemnogo O Sebe [On the Artillery and a Wee Bit About Myself], 1st ed. (Moskva: Vysshaya shkola 1984), p. 69, http://militera.lib.ru/memo/russian/yakovlev-nd/index.html.

53 G.A. Kumanev, Govori͡at Stalinskie Narkomy [Stalin’s People’s Commissars Talk] (Smolensk: Rusich, 2005), p. 229, https://stalinism.ru/images/pdf/kumanev.pdf?ysclid=l8pkutbv97765072859.

54 A.P. Rychkova, ed., ‘Spetsial’naya Svyaz’ V Sisteme Obespecheniya Gosudarstvennogo Upravleniya Rossii’ [Special Communication in the Russian State Administration Support System], in Istoriya Organov Gosudarstvennoy Okhrany I Spetsial’noy Svyazi Rossii (Moskva: Kuchkovo Pole 2012), p. 353 describes the HF telephone system; A.P. Zharskiĭ, Svi͡azʹ v vysshikh zvenʹi͡akh upravlenii͡a Krasnoĭ Armii v Velikoĭ Otechestvennoĭ voĭne 1941–1945 [Communication in the Highest Levels of the Red Army Command in the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945] (Sankt-Peterburg: Evropeĭskiĭ dom 2011), https://www.prlib.ru/item/1283884.

55 Serdi͡ukov and Zolotarev, Velikai͡a Otechestvennai͡a voĭna 1941-1945 godov : v dvenadt͡sati tomakh 11, pp. 163, 173.

56 Gorʹkov, Kremlʹ. Stavka. Genshtab., chap. 6, p. 130.

57 A. M. Vasilevskiĭ, Delo vseĭ zhizni [My life’s work], 3rd ed. (Moskva: Politizdat 1978), pp.179.

58 H.G.W. Davie, ‘The Logistics of the Combined-Arms Army — The Rear: High Mobility Through Limited Means’, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 33(4) (1 October 2020): p. 591, https://doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2020.1845091.

59 Gregory C. Baird, ‘Glavnoe Komandovanie: The Soviet Theater Command’, Naval War College Review 33(3) (1980) 40–48, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44642632; Graham H. Turbiville Jr., ‘Sustaining Theatre Level Strategic Operations’, Journal of Slavic Military Studies 1(1) (1988) pp. 81–107.

60 A. M. Vasilevskiĭ, ‘Osvobozhdenie Dondassa I Levoberezhnoi Ukrainy. Bor’ba Za Dnepr’ [Liberation of the Donbass and Left Bank of Ukraine. Storm on the Dnepr], Istoriya SSSR [History of USSR] 3 (1970) pp. 3–45; A. M. Vasilevskiĭ, ‘Osvobozhdenie Pravoberezhnoi Ukrainy’ [Liberation of the Right Bank of Ukraine], Voenno-Istoricheskiĭ Zhurnal [Military History Journal] 1 (1971). These two articles present a good example of the exchange between Stavka representative and the Centre, https://www.twirpx.com/files/science/historic/warfare/periodic/voenno_istoricheskiy_zhurnal/

61 S. K Kurkotkin, Soviet Armed Forces Rear Services in the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945 (Arlington, VA: Joint Publications Research Service 1978), p. 17.

62 V. A Zolotarev, ed., ‘№13 Komandui͡ushchim Voĭskami Leningradskogo, Volkhovskogo, Severo-Zapadnogo, Kalininskogo Frontov, 7-Ĭ Otdelʹnoĭ Armieĭ, Voenno-Vozdushnymi Silami Krasnoĭ Armii, Nachalʹnikam Glavnykh Upravleniĭ Artilleriĭskogo, Avtobronetankovogo, Tyla, T͡sentralʹnoĭ Bazy NKO’ [No.13 Commander of the Troops of the Leningrad, Volkhov, Northwestern, Kalinin Fronts, the 7th Separate Army, the Air Forces of the Red Army, the Heads of the Main Directorates of Artillery, Armored, the Rear, the Centre Base of the NKO …], in T. 23 (12-2) Generalʹnyj štab v gody Velikoj Otečestvennoj vojny : dokumenty i materialy, 1942 god T. 23, 12-2, vol. 23 (12-2), Russkij archiv. Velikaja Otečestvennaja: (Moskva: Terra 1999), pp. 22–23.

63 I.M. Golushko, ‘Razvitie sistemy upravleniia tylom’ [Development of the Rear Control System], Tyl i Snabzhenie Sovetskikh Vooruzhennykh sil Rear and Supply of the Soviet Armed Forces pp. 14–17; I.M. Golushko, ‘Razvitie sistemy upravleniia tylom’ [Development of the Rear Control System part 2], Tyl i Snabzhenie Sovetskikh Vooruzhennykh sil [Rear and Supply of the Soviet Armed Forces] (June 1981) pp. 13–17.

64 Gareev, ‘O neudachnykh nastpatel’nykh operatsiiakh Sovetskikh voisk v Veliokoi Otechstvennoi voine’; David M. Glantz, ‘Soviet Military Strategy during the Second Period of War (November 1942–December 1943): A Reappraisal’, The Journal of Military History 60(1) (1996) p. 115, https://doi.org/10.2307/2944451; Glantz, Soviet Military Operational Art, p.109.

65 S.K. Kurkotkin, Tyl sovetskikh vooruzhennykh sil v Velikoi Otechestvennoi voine [Rear of the Soviet Armed Forces in the Great Patriotic War] (Moscow: Voenizdat 1977), p. 50.

66 Fesʹkov, Kalashnikov, and Golikov, Krasnai͡a Armii͡a v pobedakh i porazhenii͡akh, 1941–1945 gg., pp. 24–29; Glantz, Forgotten Battles of the Soviet-German War (1941–1945); Glantz and House, When Titans Clashed, chaps 15 & 16 cover the relevant period.

67 Fesʹkov, Kalashnikov, and Golikov, Krasnai͡a Armii͡a v pobedakh i porazhenii͡akh, 1941–1945 gg., pp. 24–29; Glantz, Forgotten Battles of the Soviet-German War (1941–1945), all six volumes; Andronnikov, Gnezdilov, and Fesenko, Velikai͡a Otechestvennai͡a voĭna 1941–1945. Deĭstvui͡ushchai͡a armii͡a, pp. 407–8.

68 Andronnikov, Gnezdilov, and Fesenko, Velikai͡a Otechestvennai͡a voĭna 1941–1945. Deĭstvui͡ushchai͡a armii͡a, pp. 407–8; Fesʹkov, Kalashnikov, and Golikov, Krasnai͡a Armii͡a v pobedakh i porazhenii͡akh, 1941–1945 gg., pp. 24–29; Glantz, Forgotten Battles of the Soviet-German War (1941–1945).

69 Grechko, Arbatov, and Vinogradov, Istorii͡a Vtoroĭ Mirovoĭ Voĭny 1939–1945, p. 35, Table 4.

70 V.A. Zolotarev, V.I. Umatij, et al., T. 16 (5-1) Stavka Verchovnogo Glavnokomandovanija : dokumenty i materialy, 1941, vol. 16 5-1 (Moskva: Terra 1999), https://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/181446-russkiy-arhiv-velikaya-otechestvennaya-t-16-5-1-stavka-vgk-1941-g; V. A Zolotarev, V. I. Umatij, et al., T. 16 (5-2) Stavka Verchovnogo Glavnokomandovanija : dokumenty i materialy, 1942 [Russian Archive. Great Patriotic War: T. 16, 5-2 STAVKA of the Supreme High Command: documents and materials, 1942] [Russian Archive. Great Patriotic War: T. 16, 5-2 STAVKA of the Supreme High Command: documents and materials, 1942], vol. 16 5-2, Russkij Archiv. Velikaja Otečestvennaja:, 1999, http://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/210040-russkiy-arhiv-velikaya-otechestvennaya-t-16-5-2-stavka-vgk-1942-g; V. A Zolotarev, V. I ?Umatij, et al., T. 16 (5-3) Stavka Verchovnogo Glavnokomandovanija: dokumenty i materialy, 1943 god T. 16, 5-3, vol. 16 5-3, Russkij archiv. Velikaja Otečestvennaja, 1999, http://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/181447-russkiy-arhiv-velikaya-otechestvennaya-t-16-5-3-stavka-vgk-1943-g; V. A Zolotarev, V. I. Umatij, et al., T. 16 (5-4) Stavka Verchovnogo Glavnokomandovanija : dokumenty i materialy, 1944-5, vol. 16 5-4, Russkij archiv. Velikaja Otečestvennaja:, 1999, http://docs.historyrussia.org/ru/nodes/181448-russkiy-arhiv-velikaya-otechestvennaya-t-16-5-4-stavka-vgk-1944-1945-gg.

Autore: H.G.W. Davie

Lascia un commento