18 minutes

The early modern era saw distinct changes to the composition of armies, tactics, and the art of warfare itself. The return to the “classics” so advocated by the Renaissance period gave rise to the implementation of mass infantry formations, composed of pike and shot, subsequently changing the role of the medieval knight on the battlefield. Prior to these innovations, the French state had for centuries relied on the heavily armored men-at-arms to dominate the

battlefields of Europe. The technological and tactical advancements, however, forced the French, along with many other states, to remodel their armies to rise to the challenges of early modern combat. States, whose terrain discouraged the use of cavalry, turned to infantry to combat the mounted knight. On the other hand, states with suitable ground for horses continued to develop their cavalry to adapt to the Renaissance and later, Ancien Regime,

warfare. The technological advancements during the Renaissance period effectively reduced the prowess of the medieval knight. By proving his armor obsolete, the infantry units of the era drastically reduced the safety of the French noble on the battlefield, which in turn, reduced the desire of the more wealthy and powerful nobles to fulfill their traditional roles as mounted

warriors. The tactical revisions that ensued altered the social composition of the French cavalry units, ultimately leading to the birth of large scale implementation of light cavalry, the virtual elimination of traditional French heavy cavalry, and the creation of the professional officer class.

In order to fully comprehend the distinct changes that occurred to French cavalry tactics and composition, the Medieval style of cavalry fighting must first be outlined. The heavy cavalry was comprised of men of noble birth who from an early age, trained to wield the lance and sword in combat. They rode the largest of horses and were heavily armored. They fought in shallow formations, each knight selecting an individual target among the opposing cavalry formation, and “Horsemen usually fought in thin linear formations just one or two ranks deep.”[1] Fighting mounted was a noble right, the gentleman’s way of war. Their primary role on the battlefield was to execute shock action tactics, to disrupt or break enemy formations that were generally incapable of withstanding their charge. In 1445, King Charles VII established the Gendarmerie, the first permanent French companies of heavy cavalry, comprised of knights known as Gendarmes.[2] Membership into these units was limited to the nobility, which in turn reinforced the noble disdain for dismounted fighting. Despite the previously catastrophic outcomes of both the battles of Poitiers (1357) and Agincourt (1452), in which the mounted

tactics essentially killed his great- great-grandfather and great-grand father, Pierre Tenaille, better known as Bayard, provided an accurate description of the attitude of the French nobility towards dismounted combat. When ordered to dismount and lead landsknechts on foot at the siege of Padua, he replied: “the king has no soldiers in his ordinance companies who are not gentlemen. To mix them with the foot-soldiers, who are of a lower social status, would be

treating them unworthily.”[3]

Despite being highly trained, well equipped, and unquestionably brave, French heavy cavalry was often outdone by other forms of cavalry during the late medieval period. Initially the French nobility refused the possibility that other forms of mounted combat could surpass the role of men-at-arms on the battlefield. The technological advancements of the sixteenth century,

however, forced the need for new strategy and, therefore, encouraged the evolution of cavalry tactics. The French nobles, sensing the end of their dominance on the battlefield, certainly did not accept these changes readily and continued to resist their eventual replacement. The mass implementation of gunpowder weapons, and the reemergence of the ancient pike square, provided heavy cavalry with significant challenge in the sixteenth century. The arquebus and the musket were both fully capable of penetrating the armor of the French Gendarmes. The Italian Wars, more specifically the battle of Pavia (1525), demonstrated the effectiveness of the

new infantry formations and technology against French men-at-arms. At the battle of Pavia, Francis I, along with many of his knights were taken prisoner, while the rest were slaughtered by imperial infantry.[4] The Italian wars produced casualties among both sides of which the likes had never been seen. Casualty estimates at the battle of Ravenna (1512) are typically 12,000, including the majority of the Spanish colonels.[5]

Ultimately, the new weaponry and tactics shifted the balance of power in favor of the infantry, which aimed to mimic the Trace Italienne by creating mobile fortresses in the basic form of the Spanish Tercio. These formations were capable of providing both a defensive and offensive asset to the Renaissance commander, as they could repulse cavalry attacks with the pike and

simultaneously harass by use of the arquebus or musket. The invention of new weapons and the evolution of tactics eventually put an end to the ability of the French men-at-arms to conduct massive, frontal charges without suffering horrendous casualties. Therefore, the Gendarmes began to slowly develop tactics to counter the infantry, while simultaneously, new forms of cavalry emerged and were proven effective. The eventual willingness of the nobles to

adapt provided France with the opportunity to expand its retinue of cavalry types and gave rise to the prominence of the light cavalry more commonly seen in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, the reign of heavy cavalry on the battlefield had ended, and “Chivalry had become cavalry.”[6]

The inability of the men-at-arms to break Renaissance infantry formations demonstrated the need for a cavalry specific response to the new era of tactics. The invention of the wheellock pistol ushered in a new style of cavalry fighting aimed at disrupting and penetrating enemy formations without sacrificing hundreds of Gendarmes. The wheellock pistol had a

significantly shorter range than the arquebus, but it was drastically more practical to the cavalryman because of its small size. The wheellock pistol revolutionized the cavalry

tactics in the sixteenth century because it provided three distinct advantages over the lance. The pistol could easily penetrate armor, provided greater range than the lance, and allowed the cavalry unit to enfilade the enemy formation.[7]

The Germans were the first to experiment with the pistol-wielding cavalry on a large scale through their use of the Reiter. These mounted pistoliers often carried more than two pistols and were well practiced in the art of the caracole. The caracole allowed ranks of cavalrymen to charge to the enemy formation and fire their volley while staying out of the range of the deadly pike.

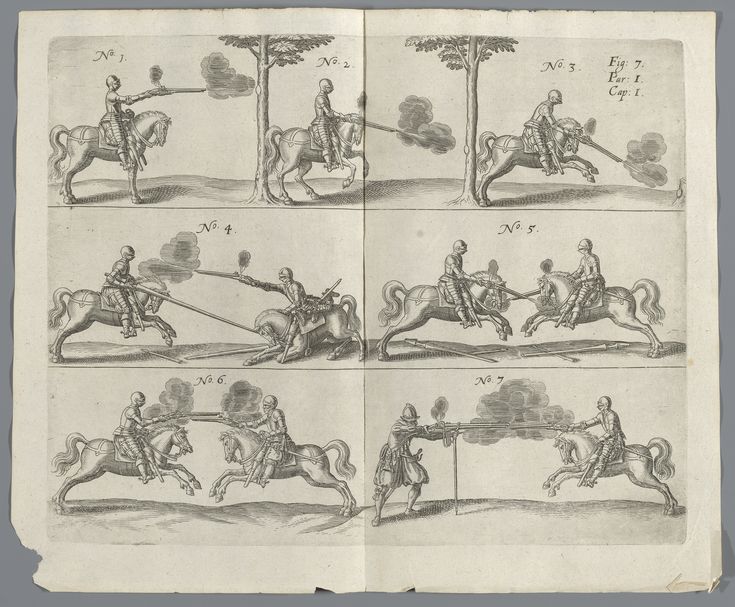

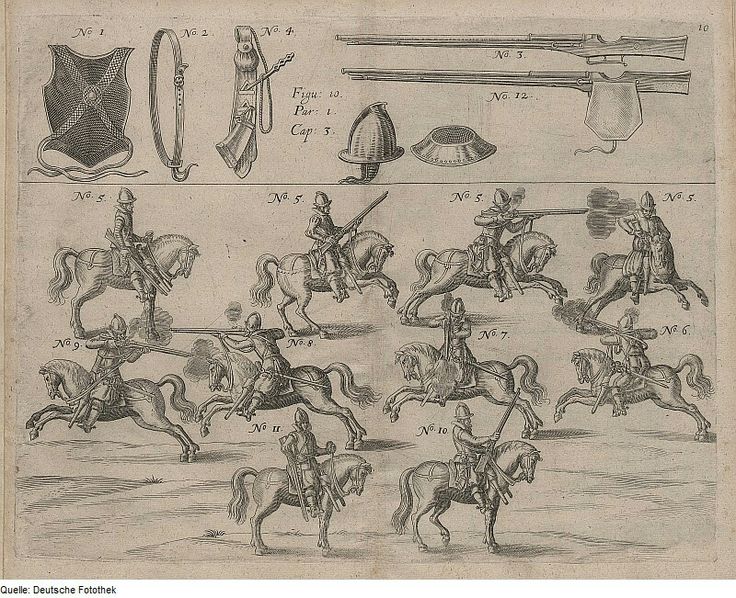

This 17th century work displays the advantages of the wheellock over the traditional lance, as interpreted by Johann Jacob Von Wallhausen.

The process would be repeated by the proceeding ranks of horses until the formation of pike collapsed. This tactic, however, required a high level of discipline and was initially rejected by many French nobles, including Francois de la Noue, who claimed that “the withdrawing part of the maneuver looked suspiciously like a retreat, and could easily become one if the targets in the enemy front line took advantage of any apparent disorder.”[8] Overall, the caracole was not devastating against infantry formations, but it did pose serious threat to men-at-arms formed en haie or en host. Francois de la Noue began to admire the German Reiter’s example and accredited their success to their ability to severely maim the first squadron of men-at-arms by shooting them in the face or thigh.[9] The Reiters, after discharging their pistols, would break into the formation and use their swords to cut down the knights still trying to strike home with their clumsy lances. By the end of the sixteenth century, the French Gendarmes began to carry the wheellock pistol in addition to their traditional weapons. Although there was still a certain degree of disgust towards the use of a gunpowder weapon by the nobility, they simply could not survive on the early modern battlefield without the unquestionable advantages the wheellock provided. The reign of Henri IV of France saw some of the most dramatic changes to both the use of cavalry and the composition of the French army itself. Henri IV explored the use of light cavalry and experimented with various formations to maximize the impact of the cavalry charge.

When the Duke of Parma encountered Henri IV near Aumale in 1592, he exclaimed, “I expected to see a general; this is only an officer of light cavalry.”[10] The duke’s statement is a testament to the changes Henri IV, the “cavalry specialist,” made to the French cavalry corps, and the resounding attitudes towards light cavalry that still existed among many nobles. Henri IV relied heavily upon the lower nobility to field his specialized cavalry force because he was not able to pay them regularly, and the lower nobility tended to concern themselves with glory instead of riches.[11] Once again, the introduction of new technologies and strategies altered the composition of the French cavalry corps, encouraging the social status of the individuals serving within it to continually decrease. Henri, under the guidance of La Noue, was successfully able to combine Reiter tactics with the shock tactics of the mounted knight and replaced the medieval en haie formations with more practical, deeper formations of cavalry.[12]

Through his innovations, Henri IV was able to re-organize the French cavalry by creating distinctions between chevaux-legers (light cavalry), arquebusiers a cheval (early dragoons), and Gendarmes, and more importantly, was able to implement the new tactics in concert with the new compositions to create a devastating effect. The chevaux-legers were often composed of lesser nobility, who were financially broken by the Italian Wars and could not afford the armor, weapons, and horses required for the heavier cavalry types.[13] These lighter cavalry units allowed the less wealthy nobles to continue to fulfill their desire to be mounted on the battlefield.[14] The light cavalry, however, offered Henri IV the ability to conduct reconnaissance, shock attacks, and to run down routing enemy. The Battle of Coutras in 1587 not only displayed the effectiveness of Henri IV’s cavalry, but also essentially demonstrated the contributions of the wheellock pistol to the death of chivalry in sixteenth century France. Henri IV used his ranged units to disrupt the enemy Gendarmes. Once they were disordered, he charged the Reiters home in their wedge formation and shattered the enemy formation under the Duke of Joyeuse. The Huguenots proceeded to shoot the men-at-arms at close range, sparing almost no one, including the Duke of Joyeuse himself, who tried to surrender before being shot in the head.[15] Under Henri IV, the lance was completely abandoned and the traditional medieval man-at-arms was forgotten. The pistol and sword replaced the lance, allowing for greater mobility and flexibility on the battlefield. Despite the advantages, the pistol provided to the cavalryman, Henri IV preferred to use the sword, or “cold steel” shock tactics, to attack the less modern Catholic cavalry.

The French wars of religion would essentially become the proving ground for the revolutionized cavalry tactics and composition. The innovations of Henri IV, initially encouraged by Francois de la Noue, and their application during the French wars of religion, forever changed the role of cavalry on the battlefield and created increased distance between the nobles and their dying dreams of the glorious heavy cavalry charge.

The evolution of the French army during this period required a new officer class and a significantly higher degree of professionalism. The virtual elimination of the heavy, noble cavalry opened the door for many French nobles to attain professional military commands, thus removing the “self- segregation” of the nobility within the ranks of heavy cavalry.[16] The complexities of warfare in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries required the officer to understand the use of combined arms and the intricacies of commanding a more disciplined force. During the dominance of the medieval men-at-arms, the noble class was often able to mask tactical incompetence with the prestige of title.

The late sixteenth and seventeenth century armies, however, demanded strong officers capable of much more than swordsmanship and the wielding of a lance. The transition from “chivalry to cavalry” marked the beginning of the transition to professional officers. During this period, for the first time, “Not all military commands went to nobles, aristocrats, and gentlemen.”[17] The

introduction of deadly gunpowder weapons, in addition to the massive costs associated with purchasing proper equipment to guard against said weapons, spurred a “reluctance” from the aristocrats to serve as men-at-arms in the French army.[18] This encouraged many nobles to join light cavalry regiments, or to become officers. Furthermore, it increased the numbers of cavaliers of non-noble birth within the re-organized French cavalry units. Nobles, who previously looked down upon serving as an officer of the infantry, recognized the renewed dominance of the foot soldier on the battlefield and began to commission into the infantry officer corps: “In the end the formidable self- discipline of the officer aristocrat was as essential to the working success of the new infantry tactics as the sergeant’s hectoring barks and heavy stick.”[19]

Despite the influx of nobles to officer positions, the cavalry units, particularly in the sixteenth century, (including the light cavalry units) remained heavily populated by nobles. During this time, the French nobles certainly chose “Eminence over efficacy.”[20] Officership, however, did not provide the protection originally sought by the nobility wishing to commission. An officer, particularly under the rule of Henri IV, was expected to stand in front of his company, “insensible to possible injury.”[21]

Henri IV of France provided the example to his fellow French officers because he led from the very front of his army, which invited insult from the Duke of Parma in 1592. Ultimately, the introduction of a variety of cavalry innovations encouraged the noble role in the officer corps, but initially it did not radically change the percentage of nobles in French cavalry units. Over time, however, the composition of the cavalry units would continue to favor the non-noble cavalier as the noble class steadily diffused into both the officer and civilian sectors of society.

The French cavalry corps is rooted in the unprecedented power the mounted knight provided for the medieval commander. Its transformation began with the death of thousands of nobles at the point of an English arrow, a Spanish pike, or the crack of a primitive firearm carried by a soldier of significantly “lesser” birth than the man who he brutally unhorsed. The challenges presented to French cavalry during the early modern era would eventually leave France with a highly skilled, diverse, and daunting cavalry force in the wars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The descended nobility of the medieval and Renaissance periods would continue to serve in French armies, not as mounted men-at-arms rearing to charge, but as educated and capable officers, as agents of France instead of representatives from individual regions. In the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries nobles became increasing less capable of protecting themselves from gunpowder weapons on the battlefield, ushering in a new era of “formality and ceremony” in which officers were to be well treated by the enemy.[22]

Consequently, the combination of revised tactics and ever advancing technology encouraged the lesser nobility to form the ranks of the light cavalry, which was becoming significantly more practical than its heavy counterparts. The thinning of heavy cavalry units simultaneously allowed the rise of the French officer corps, and the development of the light cavalry units as a combination of both lesser nobles and cavaliers without noble blood. The battlefield advancements during the early modern era initially saw the near destruction of the noble class in France; however, these developments stimulated the birth of the French light cavalry corps

and the death of the French men-at-arms.

Note:

1. Clifford Rogers, “Tactics and The Face of Battle” in European Warfare: 1350-1750, Frank Tallet and D.J.B. Trim, ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 225.

2. Treva Tucker, “Eminence over Efficacy: Social Status and Cavalry service in Sixteenth Century France,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 32, no.4 (2001): 1061.

3. Stephan Turnbull, The Art of Renaissance Warfare: From the Fall of Constantinople to the Thirty Years War (London: Greenhill Books, 2006), 176.

4. Thomas Arnold, The Renaissance at War (New York: Smithsonian Books, 2005), 174.

5. Bert Hall, Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 173.

6. Allan Gilbert, “Fr. Lodovico Melzo’s Rules for Cavalry,” Studies in the Renaissance 1, (1954):107

7. Rogers, 226.

8. Turnbull, 177.

9. Ibid, 179.

10. Ronald S. Love, “‘All the King’s Horsemen’: The Equestrian Army of Henri IV, 1585-1598,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 3 (1991): 512.

11. Love, “‘All the King’s Horsemen’” 513.

12. Ibid, 517.

13. Ibid, 520.

14. Tucker, 1061.

15. Turnbull, 186.

16. Arnold, The Renaissance at War, 116.

17. J.R. Hale, Renaissance War Studies (London: Hambledon Press, 1983), 227.

18. J.R. Hale, War and Society in Renaissance Europe 1450-1620 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998), 96.

19. Arnold, The Renaissance at War, 118.

20. Tucker, 1083.

21. Arnold, The Renaissance at War, 117.

22. Jack Kelly, Gunpowder: A History of the Explosive That Changed the World (London: Atlantic Books, 2004), 147

Autore: Thomas J. Milligan

Fonte: West Point Undergraduate Historical Review 2, Vol. 2 (2012): 13-20.

Lascia un commento