33 minutes

“Commanders seize the initiative by acting . Without action, seizing the initiative is impossible. Faced with an uncertain situation, there is a natural tendency to hesitate and gather more information to reduce uncertainty. Waiting and gathering information might reduce uncertainty, but does not eliminate it. Waiting may even increase uncertainty while providing an enemy with time to seize the initiative. It is far better to manage uncertainty by acting and developing the situation instead of waiting. Exploiting the initiative requires positive action” [1] —Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations [2]

“Israel . . . should seek to reduce to the [greatest] extent possible the duration of the Fighting: and in every military confrontation would strive for a clear, decisive and visible military victory”. —A.I.S. Nusbacher [3]

In examining the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973, one finds oneself battling between the extraordinarily successful military outcomes utilizing deep maneuver and the reality that Israeli success was often borne not by such decisive tactics, but from ruthless determination to succeed expressed as fighting spirit and high morale. That this ruthlessness was in part generated from a fear of annihilation by its Arab neighbors is a key motivation. In harnessing this motivation into tangible doctrine, there is an irony that Israeli armored doctrine builds upon Blitzkrieg and Aufstragtaktik derived from a nation that at one point in history dedicated its national resources to exterminating the Jewish people. A.I.S. Nusbacher’s study of this evolution, whilst focused on the Golan Heights in 1973, explores this natural development. In his interviews, with Israeli commanders, grudging respect is given by them to Panzer leader Heinz Guderian and German General Erwin Rommel, but their statements reflect lessons more from J.F.C. Fuller and Basil Liddell-Hart as much to hide German influence as to also show the roots of German thinking. With Rommel and Guderian setting the scene in the German experiences from World War II, moving to the Israeli experience is therefore not only logical from a theoretical perspective but, as will also be shown, logical from an examination of tactics.

This study of Israeli operations draws upon both the 1967 Six-Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War. In doing so it seeks to draw upon the best lessons for deep maneuver balanced with the failings and stark lessons learnt. There may appear to be the occasional historical schizophrenia as lessons jump from both conflicts, but by drawing the best lessons rather than attempting to mold a single operation or campaign to suit all ends, the greatest benefit for the deep maneuver commander should be derived.

Geo-Political Considerations

“Germany’s geographical position in Central Europe, surrounded by strongly armed neighbors, compelled the study of war on several fronts. Since the possibility of such a war invariably involved the prospect of Fighting against superior force, this problem, too, had to be carefully examined. . . . The strict limitations of our resources compelled the General Staff to study how a war could most quickly be conducted.[4] —Heinz Guderian, Panzer Leader

As much as the fear of annihilation should be seen as a motivating factor, Israel’s geo-political situation must be examined to set in context their view of an often-precarious existence in the Middle East. Guderian’s view of Germany’s situation in 1938, whilst stretching the reality of the time does, however, encapsulate an accurate view of Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) thinking in 1967 and 1973.

These wars may have lessened this phobia, but not exorcised it. Israel has no strategic depth and although it emerged from the 1948–1949 War of Independence with more territory than that granted in the 1947 United Nations Security Council Resolution, it nevertheless has inherited troublesome borders. With a width of just a few miles in some places to at best a few score miles, any Arab neighbor can quickly and easily attack population centers and industrial assets. This reality gives rise to a desire “that fighting must be transferred to Arab territory to the greatest possible extent.”[5] Demographically the population of Israel is insignificant when compared to the combined numbers of its Arab neighbors.[6] Even with the mass immigration evident since 1948, keeping a large standing army would inhibit economic growth. A nation-in-arms concept has therefore been sought once quipped as, “We are a nation of soldiers on leave for 11 months of the year.”[7] Great power patronage to secure resources and to possibly fall back upon for political and military support, preferably in the guise of the United States, was initially articulat-ed by its first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion. Ben-Gurion understood that a small state such as Israel could never be self-sufficient and should not consequently find itself isolated in time of war. Such patronage, whilst generating international leverage, also produces a “political stopwatch” inevitably bringing Israel and its adversaries to the negotiating table.

The correlation between ceasefire lines and ultimate political settlements is evident since 1949; hence the importance of the stopwatch. With a backdrop of constrained geography, limited manpower, and a political stopwatch, the aggressive and dynamic pursuit of deep maneuver by the IDF makes sense.

Breakthrough Battle

Finding an open flank or weak enemy area to permit deep maneuver and the subsequent space to allow forces to roam free is often simply not possible. A breakthrough battle may be needed to create the essential space requisite for deep maneuver. The subtlety between a direct attack to defeat an enemy force and an attack to permit the onward passage of a deep maneuver force is often lost in the mire of battle. The subtlety must not, however, be lost on the attacking commander. He must understand and more importantly convey to his subordinates that a swift, crushing, and decisive battle must be fought if the deep maneuver force is not to culminate.

General Israel Tal on 5 June 1967 knew he faced just such a break-through battle. He did not know that the 5th was day one of only a Six-Day War. The northernmost of three Israeli Ugdas (divisions), his task was to break through Egyptian and Palestinian forces defending the “Opening of Rafa,” a narrow tract of land between the sand dunes on the coast and the sand sea to the south.8 He knew that “the first day of the war would decide the war” and that his Ugda was to spearhead this first day.[9] Tal, a natural philosopher and the tank expert in the IDF, started his armored career as a carrier platoon sergeant in the British Army in the Second World War.

Figure 1. The Breakthrough of Tal’s Ugda at Rafa El-Arish, 5–6 June 1967. Map

created by Army University Press.

He went on to become a machine gun officer in the Haganah and only after the 1956 Sinai Campaign, when he saw the importance of the Armored Corps, did he transfer.[10] Tal brought coherence to Israeli doctrine based largely on the writings of Liddell-Hart and the experiences of Guderian, which he coupled to a strict disciplinary outlook. He was a consummate professional who understood that in a fundamentally technical Corps, only adherence to discipline and rules would succeed. In response to his critics who saw his style in direct contrast to “Kibbutz style,” he cited the following example, “A Paratrooper with a deep inner discipline is capable of fighting bravely and tenaciously, even when he is hungry and his shirt is torn. But no tank will function, even given the most rousing Zionist orations, when there is no fuel in the tank or when it has thrown a track.”[11]

Facing General Tal’s Ugda was a brigade of 20th Palestinian Division in Khan Yunis and two brigades of 7th Egyptian Infantry Division at Rafa Junction covering the coast road. A further brigade was deployed in depth. In all, the position was 35 miles deep. Tal’s aim was to break through this “crust” before the Egyptian 4th Armored Division could counterattack and stifle the Israeli deep attack across the Sinai. Tal was clear that he must succeed at the first attempt and that a time-consuming attritional battle was not an option. The Ugda had armored punch but lacked infantry and artillery balance.[12] Avoiding the obvious maneuver corridor and consequently well-defended area around the Opening of Rafal, Tal decided to attack along the coastal strip. He reasoned that the Egyptians would not have mined the coastal road and rail line nor registered their own camps in this area with artillery. Colonel Shmual Gonen, with 7 Brigade, would break through the light defenses in Khan Yunis to attack Rafal Junction from the north and drive on to El Arish. A scratch brigade commanded by Colonel Raphoul Eytan was to cross the border and attack Rafal from the south.

Colonel Menachim Aviram was to navigate along a track in the sand sea and link up with a parachute drop on El Arish airfield. At Khan Yunis, the Israelis discovered that a brigade now sat where they had anticipated a battalion. A breakdown in communication within the lead Patton armored battalion caused a delay, but the battalion was able to rally at Khan Yunis station in accordance with their preliminary orders. The sudden arrival of 60 tanks caused the Palestinians to surrender en masse. With no infantry in support, the armor could do little to capitalize on this breakdown in cohesion. The Palestinians made up for their initial shock by holding up a subsequent mechanized brigade for three days. As the lead tanks of 7 Armored Brigade pushed on to Rafal Junction, the Egyptians waited until they were within 100 meters of their positions before unleashing their ambush. Gonen then attacked in a pincer movement,

with the Centurion battalion continuing to advance along the road whilst the Patton battalion moved west.

Simultaneously the Egyptians launched a counterattack with T54 tanks. These ran straight into the pincer movement and were defeated with the loss of nine tanks. On seeing this, the Egyptian infantry went quiet and the Pattons moved into the Egyptian divisional rear area— overrunning gun positions as well as the divisional headquarters and killing the divisional commander. Gonen then committed his reserve of two Centurion companies and a jeep reconnaissance company to maintain momentum. At the Jeradi defile, the Centurions passed a sleeping Egyptian battle group.[13]

The reconnaissance company was not so lucky and after two vehicles were destroyed, the defile was closed by a now-alert Egyptian position. Eytan’s brigade fared worse. Lack of all arms training separated the tanks from the paratroopers who were then counterattacked by an Egyptian tank battalion. Tal diverted Gonen’s Patton battalion south to deal with this threat. In the interim, Israeli Fouga Magisters destroyed this Egyptian counterattack. Tal now reoriented his advance centered on Rafa Junction. The Menachim brigade’s slow advance was curtailed when the parachute battalion he was to link up with diverted to Jerusalem. Jordan had entered the war. To clear the Jeradi defile, Gonen ordered a frontal attack down the road combined with a flank attack over sand in the south. The attack was repulsed with the killing of the commanding officer (CO) and wounding of three company commanders. The second-in-command rallied the battalion and rushed the position, taking it with the loss of one tank. The Egyptians recovered from this shock and held up follow-on elements. By now, darkness had fallen and the Ugda was now spread over 30 miles centered on the obstinate block at the Jeradi defile.

Tal realized that his attack was faltering and with it any hope of breaking through the “crust.” He now reinvigorated the advance. Releasing a mechanized battalion from mopping up operations at Rafal Junction and a Patton company, he augmented Gonen’s brigade and placed at the mechanized battalion CO’s disposal the entire Ugda’s artillery, including an illumination shoot. The battalion CO urged his drivers forward to reach the defile, forcing waiting administrative vehicles off the road to allow his passage. Pausing to regroup prior to the defile, he then called for the illumination shoot to enable the centurions to give covering fire and attacked. After breaking through the defile, the battalion then spent the next four hours clearing a mile of trenches backward to the start of the defile.

The following morning, Tal’s Ugda attacked south from El Arish to link up with Yiska Shadmi’s armored brigade moving up from the south. The crust had been broken, and Israeli armor was free to strike deep toward the Suez Canal. Israel Tal created the conditions for the subsequent Israeli rout of the Egyptians in the Six-Day War.

In modern American doctrinal parlance, his was a shaping operation, but it should additionally be viewed as the decisive operation for, without this breakthrough, the overall Israeli plan would have stalled. His determination and singlemindedness, particularly during the confused night at the Jeradi defile, translated into a determined attack that maintained the objective.[14]

The mistakes over combined arms cooperation within his formation are evident, and arguably throughout this battle he also accepted risk by being off balance at various periods. His feel for the battle was, however, faultless as he constantly sought to bring about a decision and focused efforts toward this point. As an example of a break- through battle to enable deep maneuver, the 5–6 June 1967 at Rafal-El Arish is first class. Tal was also conscious of the chaos many might have perceived in his Ugda as they fought west and resisted against a natural tendency in many military minds to tidy the battlefield in order to stop and consolidate. He knew that to do so would cost him time and momentum, allowing the Egyptians, similarly working in this chaos, to gain composure.

Chaos and Balagan [15]

“How better to exemplify the natives’ improvisational capacities than in descriptive analysis of how Israelis park their vehicles in a lot. Even when there is plenty of space, the painted lines are perceived not as fixed limits but merely as suggestive points of departure”.[16] —A.I.S. Nusbacher.

In a recent British Army Review article on “The Management of Chaos,” the author used a series of complex graphs and diagrams to espouse how the modern commander must be adept at managing chaos in all its guises on the battlefield.[17] A study of the Israeli military character and their “grip” of chaos more vividly proves that in deep operations, commanders must expect, understand, and then capitalize upon chaos. Managing chaos is in short unachievable, but working within chaos and using it to one’s advantage is not. Consider the following experience from 1967: Brigadier Ben-Ari relates an episode, which illustrates Israeli acceptance of chaos not in action against the enemy, but in using internal lines of communication. On the last day of the war, his10th Mechanized Brigade was ordered to move from the Central Front near Jericho to the Golan Heights. He was given 24 hours from the warning order to have his brigade in its new position, some 180 kilometers away. He called all the brigade drivers (some 1,000 men) together and briefed them on the timing. He told them that between them and their goal there were only two roads. There were military police checkpoints, other units, and fuel dumps where logistics officers would expect signatures in return for supplies.

He did not care how they made it to the Golan, he said, just so long as they were there by the next morning at 0400. Every vehicle in the brigade was at the rendezvous by 0400. [18] Ben-Ari’s view is Clausewitzian in nature but reflects an understanding of the dynamics of movement on the battlefield, in his case even without the added complication of enemy interference. War to the Israelis was seen as a complex and at times inexplicable phenomenon that would place commanders and soldiers alike in situations unplanned for and diverse. Failure to do something in such a situation is tantamount to surrendering one’s destiny to the gods, in this case Mars and he is now on the other side.

This “fog of war” is acting on both sides and only those comfortable with chaos are likely to endure, for attempting to manage it is not possible. The contra-argument that chaos is not solely peculiar to the deep battle is true, but consider the dynamics of a commander during deep maneuver. He is operating at the limits of surveillance and communications; his logistics will at best be extended and at worst cut for periods of time. Reconnaissance and familiarity with the ground will not be complete despite any advances in technology. As far as is humanly possible, Israeli commanders such as Ben-Aris and Tal have been able to operate and succeed in such conditions. Tal’s outlook on chaos was remembered by his 7 Armored Brigade commander already on his third war by 1967, “In war nothing goes according to plan, but there is one thing you must stick to: the major designation of the plan. Drum this into your men.”[19]

Major General Ariel Sharon 1973

Ask a group of staff college students for the name of a successful deep maneuver commander and United States General George S. Patton with his flamboyant dress, language, and style will almost inevitably emerge as an archetypal deep maneuver commander and consequently he too often clouds discussion on command attributes in such a situation.[20] More often the reality is that successful deep maneuver commanders have been studious technicians such as Guderian and Von Runstedt who have understood the need to, “in the midst of emotional pressures, to juggle considerations such as the speed of tanks over various terrains, the availability of fuel, or the likelihood of the rendezvous coming off.”[21] Major General Ariel

Sharon sits as a complex character who combined an “almost implausible mixture of physical machismo and intellectual brilliance.”[22] More Patton than Von Runstedt in terms of persona, his “physical machismo” and with it a proven willingness for ferocity in combat, emerged in the early years of the Israeli State.

A fighter with the Haganah during the War of Independence, he continued combat against Egyptian troops and in one 1955 Gaza Strip operation killed 38 Egyptians. In June 1967, during the Six-Day Way, as a divisional commander, his success against the Egyptian Army played

a key part in Israel’s capture of the entire peninsula.[23] Intellectually, with a degree in oriental history, he chose to bring a professor in ancient history onto his Southern Command staff and remained scornful of his contemporaries whom he derided as, “suburbanites with degrees in economics.”[24]

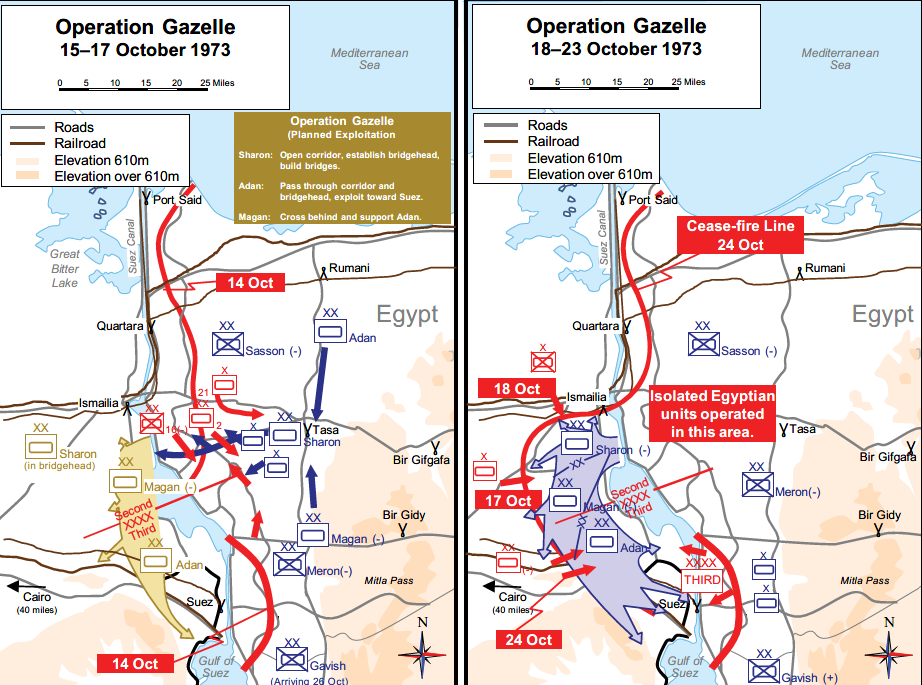

Sharon was to spearhead the IDF’s offensive deep into Egypt with the aim of reversing Israeli fortunes in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Split between the Golan and the Sinai, the IDF on 11 October 1973 faced the unnerving reality that it was being drained at a rate, in terms of men and materiel, that it could not sustain, even with American re-supply. The double specter of a Russian resupply of SAM-6 missiles to its Arab dependents also threatened to shift the air war balance between the Egyptian and Syrian air defenders and the Israeli Mirage and Sky Hawk pilots. The normal default setting for Israeli commanders faced with such a military conundrum would be an unexpected and devastating deep maneuver, an option Sharon vociferously advocated. The IDF, however, did not simply have the combat power at this stage. By nightfall, a fierce battle to clear the last remaining Syrian positions at Khusniye and Kuneitra on the Golan was won not by guile, but by a costly frontal charge.[25] The fortified piles of rubble were secured, and initial Syrian successes began to wane as they withdrew in disarray. With the Syrians now withdrawing and the Golan effectively secured, Sharon now had the conditions to cross the Suez Canal and decisively defeat the Egyptians. Operation Gazelle was authorized.[26] Sharon’s crossing of the Suez Canal in Operation Gazelle and the ultimate defeat of the Egyptian Third Army has often been cited as an exemplary example of deep maneuver and its ability to shatter an enemy’s cohesion.

One commentator hinted at “military genius.”[27] The reality behind this myth is one of vicious combat and confusion, both self-induced and from the chaos of war. The Israeli plan, hopelessly optimistic, called for three divisions to cross at the tip of the Bitter Lakes and to decisively encircle the Egyptian Second and Third Armies in 48 hours. “Hopelessly optimistic,” for the Israelis wrongly assumed that the Egyptians had reverted to their 1967 competencies. Movement to the crossing site was initially held up in vicious fighting at Chinese Farm on the two roads leading to the site.

Sharon later described this battle as, “it was as if a hand-to-hand battle of armor had taken place. . . . Coming close you could see Egyptian and Jewish dead lying side by side, soldiers who jumped from their burning tanks and had died side by side. No picture could capture the horror of the scene, none could encompass what had happened there.”[28]

The crossing itself proceeded with minimal opposition, but poor planning had the Ugda crossing in rafts in painfully slow fashion. Lack of Egyptian response, however, enabled a small foothold to be established, but no great armor reserve to break out. The initial foothold consisted of no more than 200 men, including Sharon. Meanwhile armored battles raged to the north and south of the crossing as the Ugda attempted to clear the route for heavy engineering plant. By daylight, the engineers began to establish the crossing site. The navigator of the lead barge, Sergeant Zvi, recounted, “there was a tank battle on both sides of the road and we were going down the middle. It was a battle for the junction and the junction was in their sights and they hit every vehicle that went through there. We were a slow convoy, very easy to hit. . . . There were a few hits . . . a few holes. With dawn, we got to the crossing area.”[29]

Figure 2. Operation Gazelle, 15–23 October 1973. Maps created by Army

University Press.

By 0800, 30 tanks had made it across on rafts. The Egyptian Second Army in the northern area of the crossing responded by launching a battalion counterattack, which was defeated by the small bridgehead force. This piecemeal attack was to characterize Egyptian operations over the next few days, with a succession of uncoordinated attacks lacking mass and the necessary combat power to destroy the Israeli forces. They did, however, succeed in negating an Israeli move north to interdict Second Army’s supply lines. Focus for the Israeli advance switched consequently south toward Suez. From 19 to 23 October, General Adnan passed through

Sharon’s bridgehead and exploited south to Suez, not at the 200-kilometer-per-day rate of the 1967 war, but at a more pedestrian 20 kilometers per day.[30] The constriction of Third Army in the south was only complete by 24 October after heavy fighting and a breaking by both sides of a ceasefire initiated on the 22nd.

Whatever the reality of Sharon’s operation, the effect must be remembered. The crossing and deep penetration to isolate the Egyptian Third Army effectively ended the war for Egypt, and the annihilation of this Army was only prevented by the timely second ceasefire on the 24th. Sharon, true to his character, had from the outset pushed for a rapid penetration across the canal into “Africa.” Cooler heads in the shape of General Gonen, the Southern Front Commander, resisted Sharon’s protestations.

Their viewpoints were never reconciled and at one point in a volcanic radio conversation Sharon shouted at Gonen, “if you had any balls, I’d tellyou to cut them off and eat them.”31 Sharon’s perspective on the strategic dilemma facing Israel was that conserving resources in the Sinai until the Golan had been recaptured only gave time and space for the Egyptians

to consolidate, making it more difficult for them to be destroyed later. A decisive early move would stifle Egyptian initiative, albeit the carefully choreographed Egyptian initiative.

When one looks at Sharon’s character, it is easy to see the attributes of dash, vigor, and decisiveness married to a willingness to take risks. However, as a man of clear intellectual capability, his concept and execution for the Operation Gazelle crossings were remarkably flawed in their lack of coordination and detail. Here is the dichotomy for the deep maneuver commander when honing his command and leadership skills.

In many ways he must have the confidence and imagination coupled to a ruthless determination to prosecute a bold plan, taking risks when his staff and subordinates may openly disagree with his methods. Ideally this drive must be harnessed to an acute understanding of the details of their trade if the confusion at Chinese Farm and on the Suez crossing are to be avoided. Risk is applicable to all military operations, not solely deep maneuver, but commanders must identify these risks and through forethought and planning ensure they remain understood risks and not gambles. General Ariel Sharon was guilty of gambling, not risk management, but remained lucky enough to win his gamble in October 1973.

Israeli Deep Maneuver

Unique geopolitical circumstances make the Israelis’ adoption of deep maneuver understandable. A narrow country with a small population means only quick victory on its adversaries’ soil could negate the disastrous effect any war would have on the people and economy of the country. When additionally coupled to their ebullient character against that of their neighbors, it reveals why they chose not to develop a “fortress Israel” mentality and became masters of deep maneuver. As a “textbook” example of a breakthrough battle, General Tal’s actions with his Ugda on the night of 5 and 6 June 1967 are exemplary.

His ruthless pursuit of his aim, or objective in US doctrine, enabled a massive deep penetration by the balance of Israeli forces. By not allowing himself to become embroiled in a deliberate battle of destruction, he effectively “drove through” the Egyptian positions and ensured his subordinates continued to move west instead of dwelling on the destruction of the enemy. [32]

For the deep maneuver commander, an understanding of the dynamics and pitfalls of such a battle are crucial and Tal’s lessons are self-evident. Keep focused on the end state, ensure your subordinates are of the same mind, and maintain momentum at all costs to prevent your enemy consolidating and thereby stifling your breakthrough. That the night of 5 and 6 June 1967 was chaotic would be to naively understate the ferocity of the fighting, but such a situation suited not only the character of the Israelis, but also their spirit. The willingness of commanders, at all levels, to endure this chaos and to capitalize upon its effect is a crucial style for a deep maneuver commander to adopt. By its very nature he will find himself in a part of the battlespace that in terms of his understanding is not complete and will be chaotic. Knowing and understanding the dynamics of chaos on the battlefield, and most importantly, not being overawed by such effects is a facet of command the Israelis understood and is critical for a deep maneuver commander.

General Ariel Sharon offers a complex character for study, and many writers have drawn differing conclusions from his actions as a divisional commander in October 1973. These conclusions range from genius to “military dementia.”[33] By combining his clear drive and tenacity with a willingness to take risks, one sees a style that espoused, “To hell with the

bridgehead, the important thing is to get behind the Egyptian lines.”[34] His contempt for detail and planning nearly derailed Operation Gazelle and without the “help” of Egyptian ineptitude, he almost certainly would have failed, with disastrous results for the Israeli state.

The characteristics of a deep maneuver commander if one draws from good and bad Israeli lessons should ideally be one of risk-taking and drive balanced with a keen eye for detail and the realities of the situation. General Ariel Sharon had more than enough of the former, but often scant regard for the latter. If the Israeli lessons of 1967 and 1973 epitomized the “Apogee of Blitzkrieg,” they also served as a model for the development of US Air- Land Battle doctrine. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 saw that this doctrine was never to be tested in the theatre intended, but was to be used during the 1990 and 1991 Gulf War.

Conclusion

In a central irony, the Israeli Defense Force in their wars of 1967 and 1973 demonstrated their adaptation and mastery of Blitzkrieg resulting in deep maneuver with the aim of winning quickly, while transferring the fight onto Arab territory—two aims that reflect Israel’s precarious geo-political situation.

Savage armored fighting by General Israel Tal’s Ugda on the night of 5–6 June 1967 created the conditions for the rapid deep maneuver across the Sinai so devastating in the Six-Day War. His battle is exemplary in showing that in executing deep maneuver, an assailable flank may not be

available and commanders may have to fight to create the conditions to unleash deep maneuver. His, and his subordinates’, maintenance of their aim ensured that in a chaotic night battle, they persevered. Comfort with chaos is a character trait that emerged from study of Israeli command style. Deep maneuver commanders, above all others, must be comfortable with operating in a confused and changing environment as they fight to the limit of communications and surveillance assets, no matter their modernity.

General Ariel Sharon offered an interesting study on the ideal command style for the deep maneuver commander. Bold, aggressive, and fearsomely intelligent, he nonetheless displayed rashness and lack of attention to detail that could so easily have ended in failure as he crossed the Suez Canal into Egyptian rear areas on 15 October 1973. Only piecemeal Egyptian attacks prevented his weak bridgehead, designed to enable deep maneuver, from being destroyed. His actions and decisions—along with consideration of other commanders in the guise of Guderian, Rommel, and Napoleon—demonstrated an ideal command style that encompassed not only aggression and audacity, but also deep analytical thought. It is only through such thought an initial gamble can turn into a viable plan through the identification and mitigation of risk. Sharon continued to press a gamble in October 1973 and never mitigated the risks presented.

Note:

1. This chapter is an excerpt from “Deep Maneuver: Past Lessons Identified for Future Bold Commanders,” a Military Art and Science thesis, US Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2003. Martin Van Creveld, The Sword and the Olive (New York: Public Affairs, 1988), 179.

2. Department of the Army, Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations (Washington, DC: 6 October 2017), 1-76.

3. A.I.S. Nusbacher, Sweet Irony: German Origins of Israeli Defence Forces’ Manoeuvre warfare Doctrine with Particular Reference to Israeli Land operations on the Golan Heights, 1973 (Ontario: War Studies Program Royal Military College of Canada, 1983), 43.

4. Heinz Guderian, Panzer Leader (New York: Ballantine Books, 1957), 385.

5. David Rodman, “Israel’s National Security Doctrine: an Introductory Overview,” Middle East Review of International Affairs, September 2001, 2.

6. Combined totals for Egypt, Jordan, Iraq and Syria are 116 million against 6 million Israelis. Source: CIA Fact Book 2002, accessed 6 May 2018, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/download/download-2002/index.html.

7. Rodman, “Israel’s National Security Doctrine,” .

8. Ugda is an Israeli Division. In reality there are no standing Israeli divisions so an Ugda is best described as a formation bigger than a brigade.

9. Shabtai Teveth, The Tanks of Tammuz (New York: Viking Press, 1969), 155.

10. From its initial foundations as a Jewish underground terrorist and civil defense organization, The Haganah evolved into the IDF in 1948 at the direction of David Ben-Gurion, http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/History/haganah.html.

11. Teveth, The Tanks of Tammuz, 69.

12. General Tal’s Ugda consisted of the 7 Romani Armored Brigade. The unit was probably the best armored brigade in the IDF and commanded by a disciplinarian, Colonel Shmual Gonen. The 7 Brigade was a conventional armored brigade of two armored battalions, a mechanized infantry battalion, and a reconnaissance company. One further armored brigade commanded by Colonel Menachim Aviram (composition as for 7 Brigade) and a scratch brigade commanded by Colonel Raphoul Eytan (consisting of an armored battalion and a parachute battalion) hurriedly issued armored personnel carriers in the week preceding the war.

13. A battle group is a task-organized battalion normally based upon either an armored or infantry battalion. Equates to a task force in the US Army.

14. Objective. The first US principle of war, Department of the Army, Field Manual 3-0, Operations (Washington DC, July 2001), 2-3.

15. Russian for complete mess.

16. Nusbacher, Sweet Irony, 41.

17. British Army Review (BAR) published every Autumn models itself as the “magazine of British military thought.” Whilst paid for by the United Kingdom Ministry of Defense, the editor enjoys considerable latitude.

18. Nusbacher, Sweet Irony, 39.

19. Teveth, The Tanks of Tammuz, 126.

20. Test was conducted by the author on the 14 people in his December 2002 US Command and General Staff College Staff group. Whilst not exhaustive, it was nonetheless illuminating. Napoleon also emerged high on every student’s list.

21. Insight Team of The London Sunday Times, The Yom Kippur War (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1974), 324.

22. Insight Team, 324.

23. BBC News Profile on Ariel Sharon, 1 January 2014, accessed 6 May

2018, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-11746593.

24. Insight Team, The Yom Kippur War, 326.

25. Insight Team, 239.

26. Speculation has been made that in concert with tactical victories such as Khusniye and Kuneitra, the Israelis may have rattled their nuclear saber to precipitate a Syrian withdrawal from the Sinai. Van Creveld, The Sword and the Olive, 280.

27. Van Creveld, 337.

28. Dr. George W. Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War: The Albatross of Decisive Victory (Leavenworth Papers No 21, US Army Center of Military History, 1996), 62.

29. Insight Team, The Yom Kippur War, 334.

30. Gawrych, The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, 68.

31. Insight Team, The Yom Kippur War, 337.

32. Van Creveld, The Sword and the Olive, 187.

33. Insight Team, The Yom Kippur War, 337.

34. Insight Team, 337.

Autore: Major Ronnie L. Coutts, British Army

Lascia un commento