18 minutes

Modern varieties of geopolitical theory are abundant and often conflicting. Anglo-American and German approaches tend toward a geographically oriented outlook that tends to see politics at work within a geographical setting that is, if not strictly deterministic, at least very influential (the classic theories of Halford Mackinder certainly fit this characterization), whereas French interpretations tend less towards geographical determinism and see “geography” as a culturally influenced perception that is more malleable and shapable by human action.[1]

But most modern theories share a global outlook on geopolitics that reflects the reach of modern technology, whether in terms of space-based cartographic tools or terrestrial communications and transport technology. The geographic views and scopes of action enabled by modern technology are, however, relatively recent. What does geopolitics look like in an earlier age, and what did it look like to the participants in “international” relations in an age without “nations” (certainly in the modern sense) and whose “states” were far more limited

as organizations than the global superpowers for whom modern geopolitics has usually served as an analytic guide to diplomacy and potential war? To put this question in specific terms that this article will explore, can the Norman Conquest be “Mackinderized”?

This article’s analysis of the events of 1066, which included not just the Norman invasion and conquest of Anglo-Saxon England by William the Bastard, duke of Normandy, but the near-simultaneous invasion of Harold Godwinson’s England by Harald Hardrada, king of Norway, will demonstrate that geopolitics was, in the world of 1066, a malleable text, an arena of action constructed by its participants and their views, far more than a deterministic field of play that

closely shaped the participants’ destinies. Though the eleventh century is far removed from the early 21st, this analysis suggests that even today, geopolitics is less deterministic than it looks in some modern theories.

11th Century Geopolitics

Translating geopolitics into the eleventh century is not straightforward. Both elements of geopolitical analysis, geography and politics, were not then as they are today. Modern conceptions of geopolitics arose in a world where the entire globe was both well-mapped and within reach via rapid communications (telegraphs) that have only increased in scope and speed with electronics, and militarily via slower but still relatively rapid transport technology. Communications and transport were both vastly slower in the eleventh century, and so the realm of “conceivable” geopolitics was correspondingly more restricted. The geopolitics

of 1066, in other words, was certainly not global, but was multiple and fragmented into (small) regional geographic realms. We shall focus on the geopolitical worlds into which the British Isles fit.

In addition, however, Britain did not constitute a unified nation state of the sort usually envisioned in modern geopolitical analysis, nor did any of its geopolitical neighbors, whether rivals or friends. Within the main island alone, the Kingdom of England coexisted with Scottish and Welsh lordships. Each of these including the kingdom) existed less as a “state” — an institutional structure existing in a “public” sphere over and above the individual humans who occupied it — than as a realm of personal political influence personified in the person of its ruler, though elements of institutional existence certainly attached to the ruler in some ways, including perhaps most importantly the legitimacy of the royal line from which each ruler emerged. Within these polities, more-or-less hereditary attachments between the ruler and a hierarchy of subordinate political actors filled out the sphere of action the polity operated in. Clearly, such constructions of “state” structure could conceive of and pursue the sort of long-term policies and goals that constitute the actions of geopolitics only sporadically and

inconsistently, if at all.

Such polities pursued a form of politics that was far more personal and personality driven than our contemporary world is used to. Furthermore, the dominance of individual actors in such a system of politics meant that boundaries and borders were not only less fixed and even defined than modern ones, existing more as frontier zones than as lines that could be drawn on a map, but as a consequence held far less importance in mental conceptions of how the world was put together than questions of allegiance, loyalty, and other aspects of personal relationships. One might in fact say that “geopolitics” was, in the eleventh century, “geo-personalpolitics”. In other words, geography obviously still played a role in shaping the relationships between political centers of gravity, but the meaning of “geography” was not what it is today.

As a further complication, politics was not restricted to secular political lordships. Religious affiliations and realms both underlay and at times transcended the personal politics of the secular world. This happened through several channels. First, the Catholic Church was itself a powerful “transnational” political institution that, in territorial terms, was everywhere intermingled with secular governments as an “on the ground” authority. Second, Christendom was a cultural geopolitical entity not actually coterminous with the realm of Catholic Church authority, especially after the Schism between Eastern and Western Christianity, but also because Christianity met other religions in broad frontier zones rather than at defined borders, just as political authorities met each other fuzzily. Analysis of eleventh century geopolitics in terms of competing “national interests” is thus not only impossible but places a seriously anachronistic lens on the evidence.

In short, the mental maps through which eleventh century geopolitical players would have perceived the world and projected their various interests do not conform easily to the underlying assumptions of modern geopolitical analysis. Nevertheless, if we bear the world-view differences in mind and leave open alternative modes of analysis of eleventh century warfare,[2] we can create a rough geopolitical framework for thinking about the events of 1066 and their consequences in England and beyond.

The World of 1066

In the eleventh century, the kingdom of England existed within a complex geopolitical world encompassed by the geographic British Isles, and between two geopolitical worlds: the Scandinavian North Sea; and Franco-cultural northwest Europe.

The World of the British Isles.

For much of its history between the arrival of Angles, Saxons and other closely related Germanic tribes in the fifth century and the beginning of Viking invasions in the ninth century, Anglo-Saxon England actually comprised up to seven different “Anglo-Saxon” kingdoms. These fought each other, with one sometimes establishing primacy, but also shared a culture, extensive trade within the Isles, and common social organization. That social organization was built in part on the relationship of the incoming Germanic-speaking population and the extant Celtic population of Roman Britannia, though the Romans had themselves withdrawn early in the fifth century before the Germanic invasions had commenced. The numbers of invaders

is a matter of scholarly debate, but undoubtedly comprised more males than females. There is no evidence of mass extermination of Celtic men, but the invaders seem to have established enough social dominance (especially over marriage and reproduction) that the genetic heritage of today’s English population is massively Germanic among men, but more evenly divided (to majority Celtic) among women.[3] “English” is crucial here, because the outlying parts of the Isles — Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Cornwall — farthest from the arrival zones of the Germans the in southeast both fell largely outside the realm of control of the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and retained predominantly Celtic politics,genetics and linguistics.

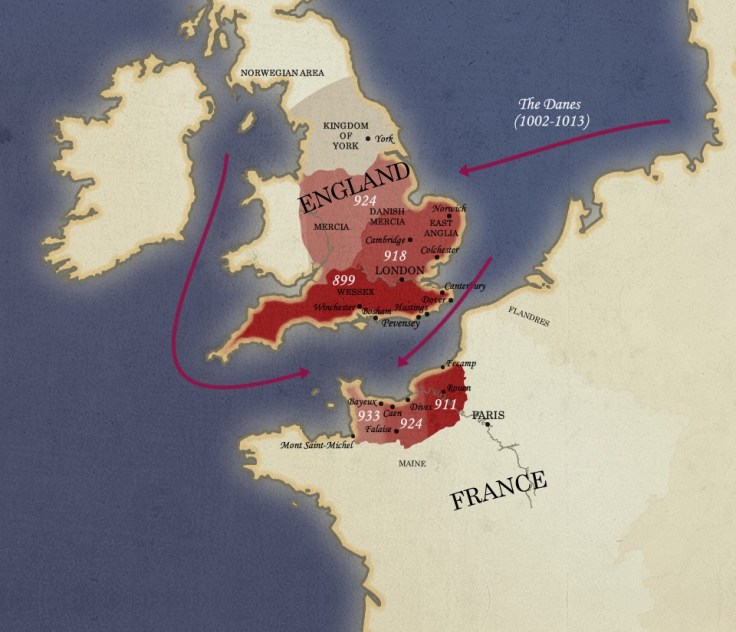

Overall, the intracultural [4] competition — military, diplomatic, ecclesiastical, cultural, and so forth — between the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and their Celtic fringe comprised the first fact about geopolitics in the British Isles for several centuries. Viking raids into the Isles, famously beginning with a raid on the monastery on Lindisfarne Island in 793, upset the equilibrium of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Over the course of the ninth century, all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms save Wessex succumbed to Viking attacks. Under the leadership of Alfred the

Great and his successors, Wessex reorganized its defenses around a set of fortified burghs, beat back the Viking invaders, and emerged as a unified Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England that claimed the cultural inheritance of all the previous separate kingdoms. Though the Celtic fringe remained separate, the unification of the Anglo-Saxon realms simplified the internal geopolitics of the Isles.The century of Viking invasions and occupations, however, had created within England a region, the Danelaw, that remained heavily influenced by Scandinavian law, politics, language, and culture, and that remained distinctive even after Wessex regained political control of the area in the later ninth century. The Scandinavian ties of the Danelaw connected the unified Anglo-Saxon England kingdom, geopolitically, to the Scandinavian world of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. In the early eleventh century, those geopolitical ties would suddenly loom large in the reign of Aethelred the Unready.[5]

The Scandinavian World.

As noted above, Viking raids into the British Isles began at Lindisfarne in 793 and continued through much of the ninth century. These raids were not state-sponsored expeditions. The beginnings of state formation and centralization in the Scandinavian world in the ninth century contributed to the raids, but in the way of provoking independent-minded local leaders to escape growing royal influence by gathering a band of supporters to “go a-viking”, or to go on

a private raiding and plundering expedition. Nor were the goals of such raids particularly “political”: their targets were, as at Lindisfarne, targets of opportunity characterized by weakly defended piles of riches, especially monasteries. (Since monks were the most prominent chroniclers of the age, this pattern contributed significantly to the Vikings’ terrible reputation.) Thus, this first phase of Scandinavian raiding, which extended from the British Isles and northern France (about which more in a moment) into the Mediterranean and eastwards

into the Slavic east (where the Scandinavian Rus laid the foundations for what eventually became Ukraine and later Russia) constituted a generalized geopolitical threat to established states such as Anglo-Saxon England, but can hardly be analyzed in terms of state-vs-state geopolitics of a modern variety.

The success of the earliest hit-and-run raids of this sort led the raiding bands to begin over-wintering in good target areas; their depredations therefore became longer-lasting and more significant. The size of the bands also grew, as the most successful attracted and absorbed smaller groups. This elevated the geopolitical threat to the political powers they attacked, though without immediately raising themselves to state-level organization. But in some places, as the raiders settled down across multiple over-winterings, acculturation to the local political forms of organization led to the formation of new states with Viking origins. We noted the emergence of Kievan Rus above; a Norse Viking band under a war leader named Rollo created the Duchy of Normandy from their base in the lower

Seine valley in the early tenth century.[6]

The “state-ification” of Viking groups proceeded both from the internal dynamics of the groups, especially the larger and more successful ones, and from efforts by their targets to “normalize” them into the established geopolitical relations of the day. The normalization of Normandy from Rollo’s band was largely at the initiative of Charles the Simple, king of West Francia, for example.

A key tool in this normalization was conversion of the Vikings to Christianity, in large part because the religion could then provide the moral basis for more reliable oaths and treaties, in addition to its being the cornerstone of western European culture. Alfred of Wessex followed this path in his campaigns to resist and then reconquer the lands subject to Viking control. At the same time, interestingly, the newly emerging kings of Scandinavia also pushed christianization as a tool in their efforts to legitimize their positions and centralize their powers. By the mid-tenth century, therefore, private Viking raids were largely ceasing,

squeezed from both ends by the forces of geopolitical normalization, especially Christianization, exerted both by their targets and by their home rulers.

But the success of geopolitical normalization in bringing private Viking raids to an end created a new dynamic, as Scandinavian expeditions continued under the newly centralized and Christianized royal powers of this northern geopolitical sphere. In short, private raiding gave way to royal expeditions of conquest in the eleventh century. These hit England in 1013 when King Sweyn of Denmark led an invasion into the Danelaw. The Anglo-Saxon king Aethelred fled to Normandy, in Franco- cultural northwest Europe, the other geopolitical region adjacent to England (see below), and Sweyn briefly became king before dying in 1014. Sweyn’s son Canute succeeded him, though not without fighting against Aethelred’s son Edmund Ironside. To help consolidate his legitimacy, he married Queen Emma, the widow of Aethelred and daughter of Richard I, Duke of Normandy. In 1018 he succeeded to the throne of Denmark when his brother died, and by 1028 he had also become king of Norway and parts of southern Sweden, creating what some historians have called the North Sea Empire. Under his reign Viking raids on England effectively ended, as England had become part of a now Anglo-Scandinavian

world, ruled by an Anglo-Scandinavian elite. The solidity of this geopolitical configuration, however, did not long outlast Canute’s death in 1035, undone by succession problems that illustrate the personal (and therefore less institutionally stable) foundations of eleventh century

geopolitics compared to modern times.[7] Canute was succeeded as king by the two sons of his wife Emma of Normandy: his own son Harthacanute, who died after two years on the throne, and Aethelred’s son Edward, who became known as the Confessor. Edward’s succession brought into relief the rivalry between the two factions of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom’s elite that had been held together by Canute’s personal leadership: the Anglo-Scandinavians, in the ascendant and under the leadership, after Harthacanute’s death, of Godwin Earl of Wessex, the

richest and most powerful nobleman in the realm, and after his death the leadership of his many sons; and the Anglo-Normans. Edward had grown up for most of his life in exile from England at the court of Robert I, Duke of Normandy. His preference for those with connections to Normandy led the Anglo-Scandinavians to effectively reduce him to figurehead status for much of his reign. Edward’s lack of an heir of his own would lead to the crucial conflict between

these factions in 1066, in which the geopolitical world of Franco-cultural northwest Europe would play a key role.

Note:

1.Among a vast sea of sources, see Halford Mackinder, “The Geographical Pivot of History”, The Geographical Journal 23:4 (1904); Pascal Venier, “Main Theoretical Currents in Geopolitical Thought in the Twentieth Century”, L’Espace Politique 12:3, 2010.

2.For example, my own suggestion that warfare can be culturally analyzed as a form of discourse by which competing groups made claims, not just about geopolitical power and possessions, ut claims about cultural identity that were made performatively, and that were not always as “winner-loser” driven as wars appear to be in a geopolitical analysis: see Morillo, War and Conflict in the Middle Ages: A Global Perspective (Polity Press, 2022).

3.Jonathan Shaw, “Who Killed the Men of England?”, Harvard Magazine July-August 2009, at https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2009/07/who-killed-the-men-england.

4.For the categories intracultural, intercultural, and subcultural see Morillo, “A General Typology of Transcultural Wars: The Early Middle Ages and Beyond”, in Hans-Henning Kortüm, ed., Transcultural Wars from the Middle Ages to the 21st Century. Akademie Verlag (2006), 29-42.

5.Marc Morris, The Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England, 400-1066 (New York, Penguin Books, 2021) provides an accessible overview; see also Richard Abels, Alfred the Great: War, Kingship, and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England (London, Longman, 1998).

6.Among many others, see Robert Ferguson, The Vikings (London: Penguin Books, 2010). The crucial influence of established political structures on this process is illustrated by the fate of the Viking settlements in Ireland. As the island lacked indigenous state-level polities, no Vikng state emerged there. The emergence of Kievan Rus in this light highlights the influence of Byzantium on the political development of that region.

Autore: Stephen MorIllo

Lascia un commento