30 minutes

The Mongol Invasion of Europe

“The greatest happiness is to vanquish your enemies, to chase them before you, to rob them of their wealth, to see those dear to them bathed in tears, to clasp to your bosom their wives and daughters.“

Genghis Khan

In 1227, Genghis Khan died at the age of sixty five. Before dying, he appointed his son, Ogatai, to be his successor as Khakan, the supreme ruler of the vast territories conquered by Genghis. By this time, the Mongol Empire stretched from the borders of Korea in the east to the Black and Caspian Seas in the west. Genghis Khan’s legacy was an army that had conquered every military force it had faced to that time, and it had developed a reputation for tactical brilliance, swift and violent maneuver, as well as brutality. They had defeated the Chin Empire and their imperial city of Zhongdu (Peking) in 1215, and the Khwarizmian Persian Empire and their key cities of Bukhara and Samarkand in 1220. They had also defeated several Russian armies in Georgia, Azerbaijan, and the Crimea, including a numerically superior force of over 80,000 at the Battle of the Kalka River in 1223. As Michael Prawdin describes it, “For forty years Genghis Khan had been compacting the nomadic races, forging them into a mighty weapon, and then leading them across the vast spaces of Asia in a campaign of victory unexampled in history, trampling mighty realms under the feet of his horses, and upon their ruins making the Mongols supreme over the world.”[32]

Now Ogatai was ruler of the Mongol Empire, and he set about to expand the empire as his father had done before him. In 1235 Ogatai decided to extend Mongol power still further by undertaking four simultaneous wars: in South China against the Sung Dynasty; in Korea; in southwest Asia; and in Europe. It is amazing that the leaders of this small central Asian nation should have the audacity to plan to carry out even one of these ambitious operations, each several thousand miles from their homeland. It is incredible – and unmatched in history – that they could plan to do all four at once. Yet they were successful in all of them.[33]

The conquest of Europe was considered the most important of these undertakings. While the expedition was put under the nominal leadership of Genghis’ grandson, Batu, the real planner and leader of the campaign was Genghis Khan’s most famous commander, Subatai (also spelled Subedei in various other sources). It was Subatai who had led the conquests of northern Manchuria and Korea, and who had pursued the Shah of the Khwarizmian Empire across Afghanistan and Persia. Even more importantly, however, it was Subatai who had led the amazing reconnaissance in force around the Caspian Sea and across the Caucasus Mountains into Russia from 1221 – 1224. It was during this expedition that Subatai and Jebei, another of Genghis’ generals, first encountered western Europeans when they took Sudak, a Genoese trading post in the Crimea. It was also during this expedition that Subatai and Jebei led the first successful winter invasion of Russia, culminating at the battle of the Kalka River. After this successful exploit, Subatai returned to join Genghis Khan and gave him a full report on the European expedition. It was at this time that he proposed a further conquest in the west.[34] The plan of campaign he drew up in the heart of Asia contemplated a war of eighteen years for the conquest of Europe.[35] It would be more than a decade, however, before that conquest would be attempted.

As early as 1236-1237, when the Mongol army was assembling, Subatai sent his warriors to subjugate all the peoples eastward of the Volga between the Kama and the Caspian, destroying their towns, slaying their men or taking them prisoner. Throughout the summer, the prisoners were drilled, taught to fight in Mongol fashion, and in December, 1237, the Mongol army, swollen by these new recruits to twice its previous strength, crossed the Volga on the ice.[36] Subatai drove his men in a rapid march first to the north, then west completely across Russia. They quickly took Ryazan, Moscow (then a relatively unimportant city), and Vladimir, the most important principality of the north. By March, 1238, most of the northern Russian lands were in Mongol hands and the Russian armies utterly destroyed.[37]

In November, 1240, after a 2 year rest on the Russian steppes, Sabatai, Batu and their army set forth again on what was to be one of the most momentous campaigns of history. The principal objective of the operations for the year was Hungary, then a well-established and rich kingdom under Bela IV. Here the Mongols apparently planned to make a permanent headquarters from which to conquer and administer the rest of Europe.[38]

The campaign began with a whirlwind sweep across the Ukraine. They crossed the Dnieper River on the ice and attacked Kiev, then the most important town in southern Russia, on December 6. Within twenty-four hours the Mongols had fought their way into the city. A few hours later Kiev was a smoking ruin. Contemporary accounts describe the actions of the army that surrounded Kiev:

“The Mongols were like dense clouds. The rattling of wagons, the bellowing of camels and cattle, the sound of the trumpets, the neighing of the horses, and the cries of a vast multitude made it impossible for people to hear one another inside the city… Batu ordered that rams be placed near the Polish Gate, because that part of the wall was wooden. Many rams hammered the walls ceaselessly, day and night; the inhabitants were frightened and many were killed, the blood flowing like water… And thus, with the aid of many rams, they broke through the city walls and entered the city, and inhabitants ran to meet them. One could see and hear a great clash of lances and clatter of shields; the arrows obscured the light, so that it became impossible to see the sky; there was darkness because of the multitude of Tartar arrows, and there were dead everywhere… During the night the people built new fortifications around the Church of the Virgin Mary. When the morning came, the Tartars attacked them and there was bitter slaughter… The Tartars took the city of Kiev on St. Nicholas Day, 6 December. They brought the wounded leader, Dmitri, before Batu and Batu ordered that he should be spared because of his bravery.”[39]

The Europeans knew nothing of the Mongols, or their origins, or their methods of making war. But word of the sack of Kiev spread quickly across eastern Europe, and suddenly it was apparent that a new and unknown force was threatening Christendom. The princes of eastern Europe began to call up their forces to meet the Mongols. Boleslaw, the King of Poland, organized his people, and Prince Henry the Pious of Silesia hastily assembled an army of 30,000 – Silesians, Bavarians, Teutonic Knights, and Templars from France. King Wenceslaus of Bohemia raised a force of 50,000 Bohemians, Austrians, Saxons, and others. Meanwhile, in Hungary, King Bela began to assemble an army of about 100,000 Magyars, Croats, Germans, and French Templars in his capital city of Buda.

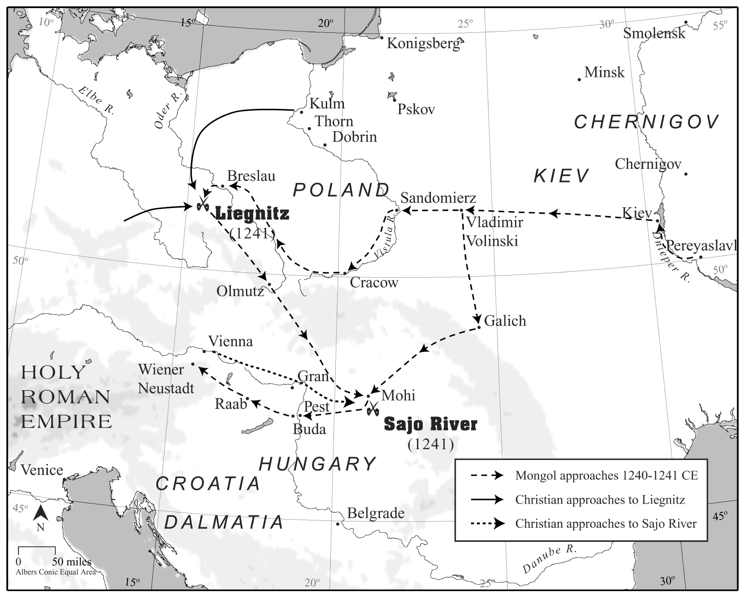

As the Mongols marched west from Kiev, Subatai divided the army into three separate hordes. Prince Kaidu with two toumans – 20,000 men – was to march northwest into Poland, then west and south through Bohemia to join the main body in Hungary. The main body of 80,000 men, under Batu and Sabatai, was to strike due west across the Carpathians into the plains of Hungary. A small force of about 10,000 men, under the command of Prince Kadan, Ogatai’s son, was sent to the south to screen the main forces’ southern flank. Subatai left about 30,000 men to hold the conquered regions in Russia.[40]

During the Russian campaign, the Mongols had driven some 200,000 Cumans, a nomadic steppe people who had opposed them, west of the Carpathian Mountains. There, the Cumans appealed to King Bela for protection, in return for which they offered to convert to Western Christianity. A mass conversion would enhance Hungary’s prestige with the Pope. Moreover, the Cumans pledged over 40,000 warriors, experienced in the Mongols’ mobile steppe warfare, to Hungary’s defense. Bela gladly accepted the offer, but many of his nobles distrusted the Cumans. His decision gave the Mongols an official excuse to make Hungary their next object for conquest.[41]

King Bela felt he was ready for the Mongol attack. He had done everything orthodoxy demanded – he had blocked the Carpathian passes, he had sent reinforcements to their commander and he had summoned a parliament to discuss what should be done. Had he been facing the kind of army he was used to, he might have saved his kingdom. The Mongols, however, were something quite new. They brushed aside the frontier forces, smashed their way through the passes into the spreading plains beyond, advancing forty, fifty, even sixty miles a day. Their advance was far too swift to allow the Hungarians to properly react and was too swift for parliamentary discussion. It took only two days to cross the mountains and another three to reach the capital – events had already outpaced the speed of Bela’s reactions.[42]

While the Mongols ravaged the countryside, Bela moved his army of 100,000 across the river to Pest. Subatai then pretended to retreat to the northeast, for about 100 miles. Bela and his army followed to the Mohi Plain, reaching the Sajo River on April 10. The Mongols pretended to continue their retreat, crossing the river and leaving Bela in command of the plain and of the only bridge across the river. He camped for the night beside the bridge, forming his wagons into a wall around his camp. He sent a small force to hold the far end of the bridge.

Just before dawn the next morning the Hungarian bridgehead defenders found themselves under a hail of stones and arrows, “to the accompaniment of thunderous noise and flashes of fire.” Most likely, this was the usual Mongol employment of catapults and ballistae, using Chinese firecrackers to increase terror. In any event, this was a thirteenth century version of a modern artillery preparation. It was followed closely, as in modern warfare, by fierce assault.[43]

The defenders of the bridge, stunned by the noise, death, and destruction, were quickly overwhelmed and the Mongols streamed across. Bela’s main army, aroused by the commotion, hastily sallied out of the fortified camp. A bitter battle ensued. Suddenly it became apparent, however, that this was only a Mongol holding attack. The main effort was made by three toumans, some 30,000 men, under the personal command of Subatai. In the predawn darkness he had led his troops through the cold waters of the Sajo River, south of the bridgehead, then turned northward to strike the Hungarians’ right flank and rear. Unable to resist this devastating charge, the Europeans hastily fell back into their camp. By 7:00 that morning the laager was completely surrounded by the Mongols. For several hours they bombarded it with stones, arrows, and burning naphtha.[44]

At last the Mongols used the tactic they had perfected far to the east. They simulated a weak point in their encirclement which offered the entrapped forces an illusory escape route. Bela’s desperate men streamed through the gap, their line of flight marked by discarded helmets, shields and swords. Suddenly the escaping soldiers discovered that they had fallen into a Mongol trap. Mounted on swift, fresh ponies, the Mongols appeared on all sides, cutting down the exhausted men, hunting them in the marshes, and storming the villages in which some of them attempted to take refuge. In a few hours of butchery the Hungarian army was completely destroyed with between 40,000 and 70,000 dead. Not more than 20,000 Europeans survived the battle and the pursuit.[45]

While Subatai’s army was advancing into Hungary, Kaidu’s army swept into Poland on a broad front. In February 1241, they entered the territory of Lublin, burning the cities of Lublin and Zawochist and laying waste to the countryside. They were moving slowly and after crossing the frozen Vistula on the ice they were able to sack Sandomir and plunder its Cistercian monastery without being threatened by a relieving army. The Poles had obviously been taken by complete surprise. With no apparent opposition, the conditions seemed ideal for a quick conquest. Kaidu’s objective was to draw the northern European armies away from Hungary, and it did not yet look as though these armies had even been mobilized. Although his army was already dangerously small, he decided to divide it and spread alarm over as wide an area as possible; in the last resort the Mongols could retreat faster than any European army could advance.[46] While one of his toumans rode northwest to attack Mazovia, Kaidu took a calculated risk and continued his advance southwest, directly toward the Polish capital at Cracow.

Raiding and burning and drawing attention to itself, Kaidu’s vanguard advanced to within a few miles of Cracow and then slowly turned back as though returning to its camp with its plunder and prisoners. Vladimir, the Palatine of Sandomir and Cracow, rode out of the city in considerable strength and attacked.[47] The Mongols broke and fled under the initial attack by Vladimir’s army, but once again a numerically superior European force had been lured into an old Mongol death trap. When the Mongols did not reappear the soldiers of Vladimir’s army began to advance. On 18 March, at Chmielnik, only eleven miles from Cracow, Kaidu ambushed them. Vladimir and most of his soldiers died in a hail of Mongol arrows.

Breslau, the capital of Silesia, was the next target for Kaidu’s army. But shortly after beginning his siege of the city he learned that Duke Henry of Silesia had assembled an army of the northern princes at Liegnitz and that King Wenceslas of Bohemia was marching to join him. Kaidu abandoned the siege, alerted Batu and Subatai, and set out at full speed to reach Liegnitz before Wenceslas.[48]

On April 9, 1241, Duke Henry marched out of his city of Liegnitz (now the Polish city of Legnica) to meet the dreaded Mongols. Henry’s army was the last left to oppose the Mongols in Poland. Unaware of exactly where King Wenceslas was and fearing that the Mongols might be reinforced if he waited too long for the Bohemian King, Henry left the protection of Liegnitz and advanced toward the town of Jawor. Duke Henry’s army of about 30,000 consisted of Polish Knights, Teutonic Knights, French Templars, and a levy of foot soldiers. Indeed, the very core of northern European chivalry had assembled under his banner.[49]

Unlike Henry, Kaidu knew where Wenceslas was – only two days’ march away. The Mongols were already outnumbered and could not risk allowing Henry and Wenceslas to join forces. Therefore, when Henry reached a plain surrounded by low hills not far from Liegnitz, called the Wahlstadt, or “chosen place,” he found the Mongols there waiting for him. The Mongol army did not look very large. It was not for some time that the European knights learned how the Mongols attacked in such close order that a formation of 1,000 horsemen seemed no bulkier than 500 knights.[50] Henry drew his forces up in four squadrons and placed one after the other on the Wahlstadt.

When the engagement began, the Europeans were disconcerted because the enemy moved without battle cries or trumpets; all signals were transmitted visually, by pennant and standard. The first of Henry’s divisions charged into the Mongol ranks to begin the usual hand-to-hand combat, but the more lightly armed Mongols on their agile ponies easily surrounded them and showered them with arrows, sending them into headlong flight. The second and third divisions of heavily armed and mailed knights attacked next, and this attack seemed successful – the Mongols broke into what appeared to be an orderly retreat. Encouraged, the knights pressed on their attack, eager to meet the Mongols with lance and broadsword. Henry then led his fourth battle group into the Mongol lines to engage in close combat. Things were not as they seemed for the knights, however. Once again the Europeans had fallen victim to the Mongol trick of feigned retreat. As the knights continued their pursuit and extended their lines, they drew further away from their infantry. Suddenly the Mongols swept to either side of the knights and showered them with arrows. Other Mongols had lain in ambush, prepared to meet the knights as they fell into the trap. Whenever the Mongols found that the knights’ armor afforded effective protection against their arrows, they simply shot their horses. The dismounted knights were then easy prey for the Mongol heavy cavalrymen, who ran them down with lance or heavy saber with little danger to themselves.

The Mongols also employed one further trick. Smoke from dung fires drifted across the battlefield between the infantry and the knights who had charged ahead, so the foot soldiers and horsemen could not see each other as the Mongols fell upon the knights and virtually annihilated them.[51]

Duke Henry, most of the knights and noblemen, and the greater part of the infantry, were left dead on the field of Wahlstadt. The chroniclers record the losses as between 30,000 and 40,000.[52] In accordance with a Mongol custom used to count the dead, an ear was cut from each dead European. The Mongols filled nine sacks with ears.[53] Duke Henry’s head was cut off and carried as a trophy on spear-point outside the walls of Liegnitz.

The double catastrophe of the Sajo River and Liegnitz, fought within days of each other, stunned Europe. Europeans were shocked at the news of the two thorough defeats of some of the finest soldiers they had at the time. Even more astonishing was the discipline, order, and swiftness with which the Mongols had achieved their victories. Europeans had never before seen such military skill in the ability of large forces to maneuver rapidly on the battlefield to defeat larger, well-equipped armies. The Poles and others attributed the Mongols’ success to supernatural agencies or suggested that the Mongols were not entirely human. The very name given to the Mongols by the Europeans, “Tartars,” derived from the word “Tartarus,” the ancient world’s Hell. Mongols, then, were more devils than humans. They had risen from the Pit itself to overthrow Christendom.[54]

After the Battle of Liegnitz, Kaidu began to march against Wenceslas, who had a cumbersome army of 50,000 about 50 miles to the west. Shortly after beginning his movement, however, Kaidu received word from Batu of the victory over Bela at Sajo River, and instead swept south to join Subatai and Batu in Hungary.

To the far south the Mongol horsemen under Prince Kadan took Bisritz, Klausenburg, and Grosswardein as they moved across Transylvania. Two days after the Battle of Liegnitz they defeated a Magyar army outside the fortress of Hermannstadt, which they then assaulted and captured. After that Kadan moved north to meet Subatai, Batu and Kaidu in Hungary.

In little more than a month the entire countryside from the Baltic to the Danube had been occupied and ravaged by the Mongols; Poland, Lithuania, Silesia, and Moravia had been laid waste no less than Bukovina, Moldavia, Wallachia, and Transylvania. The towns were heaps of ruins, the land was depopulated, armies had been dispersed, and fortresses taken by storm. Hungary was a rich land, offering abundant scope for plunder; but what would happen after that? Which country would be the next victim?[55]

After resting for the summer and fall months in Hungary, the Mongol invasion of central Europe began as Subatai’s soldiers crossed the frozen Danube on Christmas Day 1241. They soon took Buda, Gran, and other western Hungarian towns. While a reconnaissance in force crossed the Austrian border, Kadan took one touman and turned south toward Zagreb to pursue Bela. Kadan passed along the shores of Lake Balaton and followed his quarry through Croatia; he did not venture to attack Spalato or Trau, but destroyed Cattaro and penetrated Albania to within a few miles of Scutari, the most southerly limit of the Mongol operations in Europe.[56]

While Kadan in the south and Batu in the west were completing the conquest of Hungary, the Mongol advance guard had already crossed the frontier of the kingdom. The savage horsemen reached Komeuburg, to the northwest of Vienna, and Wiener Neustadt in the south. “Without having sustained any harm, they seized a number of persons and cattle, and then returned to Hungary,” reports one chronicler. They had reconnoitered the united forces of the Dukes of Austria, Carinthia, and many principalities, and in adjoining Bohemia was the army of King Wenceslas – while Subatai and Batu were making ready for a new campaign.[57]

But early in 1242, Subatai and Batu received a message which had come 6,000 miles from Karakorum to Austria. Ogatai was dead. Batu wanted to remain in Europe and continue the conquest. But Subatai reminded him that the Law of the Yasak and the decree of Genghis Khan required all princes and chiefs to return to Karakorum for a Kuriltai and the election of a new Khakan. Hungary was abandoned. The Mongol army rode back across the Danube destroying everything in its path. The populations of villages and towns were slaughtered without mercy, all the barns and warehouses were systematically burned, and the already devastated departments of southern Hungary and Transylvania became a wilderness. Proclamations were posted in the Mongol camps declaring that all prisoners might return to their homes, but those who left were pursued and slaughtered.[58] Just as quickly as the Mongols had come to Europe they vanished. Although the Mongols returned to Karakorum with the intent of postponing the invasion of central Europe for another time, that time would never come. Europe was saved.

Not until after the Mongols had departed did the full measure of the devastation wrought in Hungary, Silesia, and Poland become plain. It surpassed the worst expectations. From 60,000 to 80,000 men had been slain on Mohi heath; in Pest alone, 100,000 persons were killed; and in other towns and fortresses all the inhabitants had been slaughtered except for a few refugees and prisoners the Mongols had taken with them.[59]

The campaign into Europe, so meticulously planned and so brilliantly executed, was a marvel of the military art and the masterful hand of Subatai, a genius for war not inferior to Genghis Khan himself. Since the Mongol soldiers were natives of a cold climate and were well equipped to fight in snow, Subatai preferred a winter campaign, when communication was facilitated by frozen rivers. In the absence of maps and charts which guide a modern commander, the Mongols utilized the careful collection of information from spies and deserters who revealed the state of the roads, the distances to the next towns, the presence of enemy detachments, and the level of morale in enemy camps. The armies Subatai led into Europe were not numerically overwhelming, but their discipline and organization were far superior to that of the feudal military forces of the west. That the Mongols were able to achieve such dazzling success in lands so far from their home base and whose geography and resources were entirely unfamiliar to them is amazing indeed. The geographical scope of the fighting alone encompassed the greater part of eastern Europe. The Mongols’ planning and coordination of movement coupled with their clockwork precision enabled them to surround, defeat and pursue the largest and finest western armies of the time. They brilliantly overcame difficult problems of supply and skillfully maneuvered large formations on unfamiliar European terrain. In every aspect of the Mongols’ conquest of eastern Europe, it is apparent that the Mongol leaders were masters of the art of war.[60]

The Legacy of Genghis Khan and the Mongols

“With Heaven’s aid I have conquered for you a huge empire. But my life was too short to achieve the conquest of the world. That is left for you. My sons will live to desire such lands and cities as these, but I cannot.“

Genghis Khan

The Mongol conquests, which shook the globe, were of a scope and range never equaled. The Mongols were invading Java and Japan thirty years after their armies stood on the frontiers of Germany and the shores of the Adriatic. After we have allowed for the military genius of Genghis Khan, the world’s greatest “organizer of victory,” the geographical advantage of campaigns launched from the steppe, and the weakness and confusion of the states that were attacked and demolished, the result is awe-inspiring.[61]

One cannot dismiss the great military lessons learned from studying the campaigns of Genghis Khan and his superb generals, especially Subatai. The military techniques of the Mongols were comparable to those of the ancient Huns or Scythians, but they were employed with greater strategic vision and more proficient leadership, and the results were commensurably more startling.[62] They revolutionized maneuver warfare of their time, combining speed with coordinated shock action to completely overwhelm their enemies. They developed military systems of command and control and communications that simplified large scale maneuver operations and bewildered their enemies. Their use of deception at every echelon enabled them to systematically destroy numerically superior forces with ease. Their combined arms approach to warfare, including the use of artillery-like preparations followed by massive cavalry and infantry attacks, was a brilliant example of their military genius and still has application in today’s style of maneuver warfare. In every aspect the Mongols had the greatest army of its time, with the best discipline, organization, leadership, and cavalry.

While nobody can deny the impact that Genghis Khan had on history, assessments of his achievements have varied. He is either viewed as “the greatest gangster of all time” or as “the noble savage who…took the Mongols from primitive obscurity to the pinnacle of world power.”[63] One thing cannot be disputed, however. Genghis Khan was one of the most successful empire builders because, unlike the states established by many renowned conquerors, that of the Mongols did not fall apart upon the death of its founder. In this Genghis Khan was more effective than both Alexander the Great and Charlemagne. He left not only an empire and a splendid army but the foundations of an administration and the basis of a legal code, the Yasak. He also left a family whose respect for the memory of Genghis Khan was such that, instead of quarreling over his inheritance, they generally managed to agree upon the succession.[64]

The creation of the Mongol Empire was the last great nomad expansion in European and Asian history. There were to be steppe empires in the future, but subsequent to the decline of the Mongols the nomads were on the defensive against settled civilizations that, for a variety of reasons, gradually and inexorably tipped the balance of power in their own favor.[65] The new inventions of gunpowder and firearms were soon applied to the art of war. The battles in the future would no longer be decided by the skillful aim of the archer and the swiftness of the horseman. The gun was a monopoly of civilization, and a few rounds of artillery could neutralize sizeable numbers of bowmen and cavalry. Militant nomadism was soon superannuated, its military power was broken, and its horsemen rode out to conquest no more.[66]

Note:

[32] Michael Prawdin, The Mongol Empire, Its Rise and Legacy (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1961), 233.

[33] Dupuy, 98.

[34] Ibid., 90.

[35] Prawdin, 246.

[36] Ibid., 249-250.

[37] Dupuy, 99.

[38] Ibid., 100.

[39] Brent, 118.

[40] Dupuy, 101.

[41] Erik Hildinger, “Mongol Invasion of Europe,” June 97; available from http://www.thehistorvnet.com/MilitarvHistorv/articles/1997/06972 text.htm; Internet; accessed 23 Feb 2000.

[42] Brent, 121.

[43] Dupuy, 106.

[44] Ibid., 106.

[45] Brent, 125.

[46] Chambers, 96.

[47] Ibid., 96-97.

[48] Ibid., 97.

[49] Hildinger.

[50] Prawdin, 257.

[51] Hildinger.

[52] Prawdin, 259.

[53] Hildinger.

[54] Brent, 127.

[55] Prawdin, 265.

[56] J.J. Saunders, The History of the Mongol Conquests (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971), 87.

[57] Prawdin, 269.

[58] Chambers, 113.

[59] Prawdin, 271.

[60] Saunders, 84 & 88.

[61] Ibid., 175.

[62] Ibid., 191.

[63] Nicolle, 45-46.

[64] Ibid., 46.

[65] Ibid., 46-47.

[66] Saunders, 191.

Autore: Joe E. Ramirez Jr.

Fonte: Defense Technical Information Center – (DTIC)

Lascia un commento