21 minutes

Introduction

Genghis Khan was born sometime between 1155 and 1167 (some sources place 1162 as the date, but there is no confirmation) into the Borjigin clan on the bank of the Onon River, east of Lake Baikal. He was born with the name Temujin (or Temuchin, based on which source you use), which means “iron worker” in his native language.[3] As a youth he learned of the harsh existence of the Mongol people, and of the need to be a skilled hunter and fighter. His father was killed when Temujin was only 13, and he quickly rose to power among several of the Mongol tribes. By the time he was nineteen years old, Temujin had 13,000 followers in his camp.[4]

At about the age of twenty the young leader adopted a regular battle formation and organization for his warriors – one that was apparently new among the Mongols. Ten men made up a squad, ten squads made up a company, and ten companies made a group, or guran, of one thousand men. All of the warriors were mounted on small, sturdy horses known as Mongol ponies.[5] Temujin set out to train his warriors to ride, turn, and attack as units until they became extremely skillful at riding and fighting together. Through rigorous exercises and wargames, he quickly turned his gurans into highly disciplined and skilled fighting units. Because they trained and practiced as units, Temujin’s men could move without delay in response to his orders. Never before had Mongols observed such discipline.[6] Thus, at an early age, Genghis (Temujin) began to demonstrate the military genius that would later help him conquer half the world.

He quickly abandoned the usual methods of defense favored by the Mongol tribes at that time and adopted a more mobile defense centered on heavy cavalry. During a battle against Targutai, his father’s cousin, for leadership of his father’s tribe, Temujin used light cavalry as a screen, backed up by the heavy cavalry placed in front of a thick forest. When Targutai’s horsemen attacked, Temujin’s light cavalry fired a volley of arrows, then moved to the rear, behind Temujin’s main line of heavily armed cavalry. The solid units of heavy cavalry then charged against Targutai’s infantry, quickly overwhelming them. Targutai’s warriors had never before experienced the powerful shock of a massed cavalry charge and 6,000 were killed. Targutai was one of the many enemy prisoners and he was executed by order of Temujin.[7] Temujin soon became the undisputed leader of his tribe, and his astounding success attracted more and more Mongols who wished to join such a great and powerful leader.

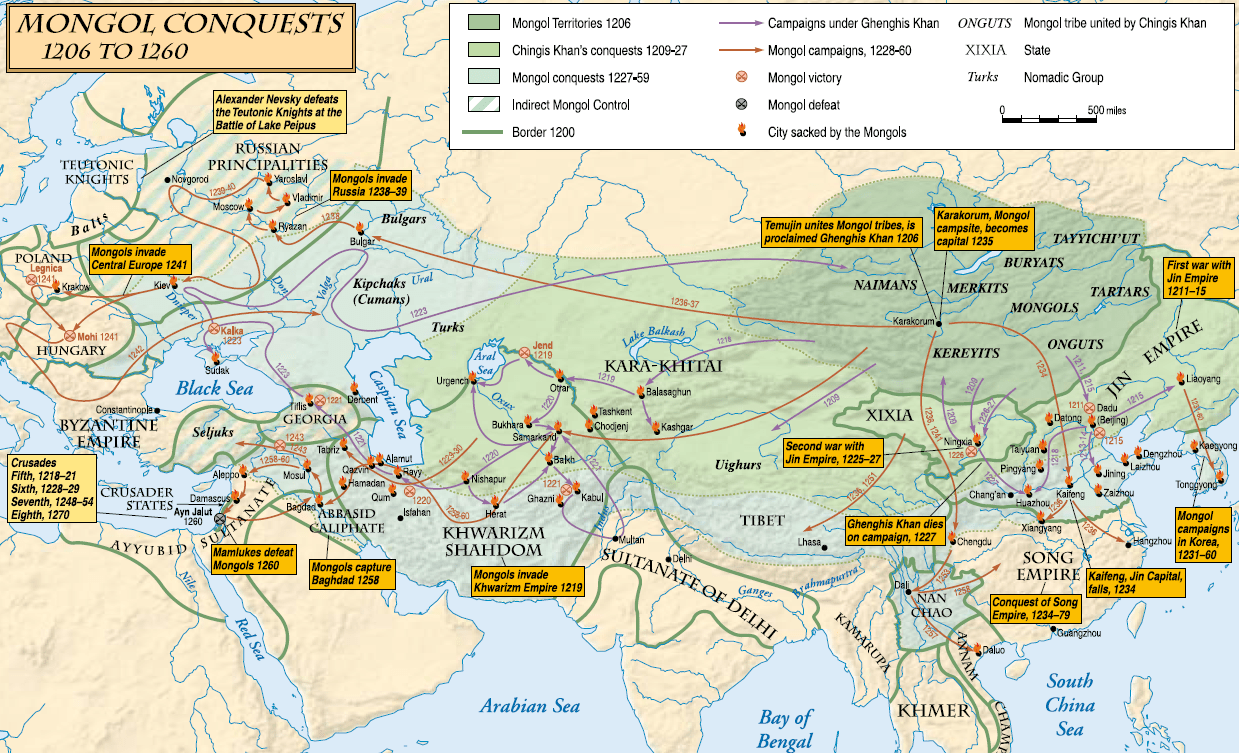

In the year 1190, Temujin was chosen Khan of the Borjigin Mongols by a Kuhltai, or council of the chiefs. While the tribal chiefs of the clan saw their new Khan as a leader only in time of war and in great hunts, Temujin had other ideas: he had begun to see the possibility of a Mongol nation and of a permanent, well-trained army.[8] It is very clear that Temujin, at an early age, wanted to unite all the Mongol tribes under his rule and then expand that rule outward from the Mongolian steppes. He had clearly defined expectations of a large, well-trained, mobile army that could maneuver great distances and conquer any other army it encountered. But first he had to defeat his rivals within the Mongol tribes before he could unite his people and begin his expansion of the Mongol Empire.

In 1204, at the Battle of Chakirmont, Temujin defeated the Naimans, a comparatively civilized people who had a written language and were the only Mongolian tribe that had not recognized him as Khan. After defeating the Naimans, he invited the Naiman warriors to join his army, and began efforts to assimilate the Naiman people with his own tribes by intermarriage. Temujin recognized that the Naiman culture, with its written Uighur language, was far more advanced than that of the more primitive tribes of eastern and central Mongolia. So he adopted this culture and moved his own capital to the chief Naiman city of Karakorum. Temujin was now the unchallenged ruler of the land from Siberia to China with 400,000 tents and a population of more than 2,000,000 people.[9]

With the submission of the Naimans, Temujin became the effective ruler of all Mongolia. In 1206 he assembled a great Kuriltai near the source of the Onon River. Here he was proclaimed Khakan, supreme Khan of all Turkish and Mongol tribes “who lived in felt tents” in eastern Asia. He was also given the name Genghis Khan, “Oceanic Ruler,” signifying that he wielded great power throughout the known world. A famous shaman named Kokchu declared that Genghis was Khan “by the strength of the Eternal Heaven.”[10] Genghis Khan was now the ruler of all the Mongol tribes, and he quickly set out to unify the people and to bring order and discipline to the land. He quickly established a Code of Laws, or Yasak, which he would use to establish discipline and a sense of equality throughout his empire. Even more importantly, he set about building and training his army based on the lessons he had learned during his rise to power. This was where his strength lay, and he sought to build and train an army that could help him expand his Mongol Empire. Genghis now energetically devoted his efforts to establishing his military organization throughout all of Mongolia, and in training and equipping all Mongol warriors to fight in accordance with his now well-established methods of warfare.[11] Genghis Khan had under his hand a new force in warfare, a disciplined mass of heavy cavalry capable of swift movement in all kinds of country. Before his time the ancient Persians and the Parthians had perhaps as numerous bodies of cavalry, yet they lacked the Mongols’ destructive skill with the bow as well as their savage courage. In the Mongol horde he had a weapon capable of vast destruction if rightly handled.[12] It was this weapon – trained, skilled, and well-led – which Genghis Khan used with ruthless effectiveness to rapidly expand his empire like no other leader before or since.

Mongol Military Organization and Training

“Be of one mind and one faith, that you may conquer your enemies and lead long and happy lives.“

Genghis Khan

In the thirteenth century the Mongol army was the best army in the world. Its organization and training, its tactical principles and its structure of command would not have been unfamiliar to a soldier of the twentieth century. By contrast the feudal armies of Russia and Europe were raised and run on the same lines as they had been for several hundred years and their tactics would have been unimaginative to the soldiers of the Roman Empire.[13] After becoming Khakan, Genghis Khan retained the system he had developed earlier for organizing his army, with squads often men called arban, squadrons of one hundred called jaghun, and regiments or gurans, of one thousand men. Ten of these gurans were combined into a touman, or division, often thousand horsemen. Two or three, or sometimes more, toumans were combined into a horde, or army corps.[14] The commander of each Mongol unit was selected on the basis of individual ability and valor on the field of battle. He exercised absolute authority over his unit, subject to equally strict control and supervision from his superior. Instant obedience to orders was demanded and received; not since the time of the Romans had discipline been so strictly enforced. Yet mutual trust and loyalty existed between all ranks.[15] Every Mongol soldier was a horseman, and all were expert in the use of the bow, the curved sword known as the scimitar and the battleaxe. The recurved bow was by far the most famous of the Mongol weapons. Each warrior normally carried two bows: a light bow which could be fired easily from horseback, and a heavier bow which was designed for long range use from a ground position. This heavy bow had an average draw weight of 166 pounds, much more than the strongest contemporary European bow, the British longbow. As could be expected, the troops carried several quivers each. Some were filled with arrows suitable for use against warriors and horses at closer ranges, while another quiver held arrows for penetration of armor or for long range shots.[16] Genghis Khan divided his horsemen into heavy and light cavalry, the former relying largely on their lances, the latter, who were perhaps twice as numerous, on their mobility and their skill with the bow. These last carried a bundle of javelins, the Mongolian lasso and a sword or axe, with a shield and helmet for protection. The heavy cavalry, however, wore complete body armor of leather reinforced with metal and carried a heavier sword or axe. Sometimes they, too, used their skill as archers – the Mongols were always fearsome with the bow, even when shooting from horseback.[17]

Every soldier had two or three ponies. During a march the extra mounts Would be herded along behind the touman. When speed was required, the troops would change ponies two or three times a day, to keep the ponies from getting too tired. If possible, the troops always changed to fresh ponies before a battle. This system of extra mounts was one of the reasons why the Mongols could march for days at a time at rates of speed that were incredible to their enemies.[18] With a strong neck, thick legs, dense coat, immense endurance, steadiness, and sureness of foot, the Mongol pony was ideally suited not only to its environment but also to the Mongol style of warfare.[19]

The precision with which the Mongol army performed their intricate maneuvers on the battlefield was only attained after months of initial drilling which was reinforced by continuous training. For the bulk of the Mongol army, military training revolved around hunting. The most important hunt was the annual nerge, a massive expedition in search of game to provide meat for the long Mongolian winter. An expansion of the Mongols’ favorite sport, the great hunt (nerge) was conducted like a campaign and designed to generate a “team spirit” throughout the army, temper its discipline, and enhance its morale. For the Mongols no other sport or military exercise could have been more effective. It was held at the beginning of each winter in peacetime, lasted for three months and involved every soldier. At a signal from the Khan, the entire army, fully armed and dressed for battle, would ride forward in one line, driving all the game before it. As the weeks went by and the game began to build up, the wings of the army would advance ahead of the center, and when they had passed the finishing point, would begin to ride in to meet each other, totally encircling the game. Once the wings had met, the circle would begin to contract with the line deepening, until, on the last day of the drive, the Mongol army would become a huge human amphitheater with thousands of terrified animals crowded into its arena. On the final day the Khan rode first into the arena to take his pick of the game, and when he had finished and returned to a hill overlooking the army, it was the turn of the soldiers.[20] The tactics of the nerge were applied to Mongol warfare, utilizing the skill, discipline, and command and control demonstrated during the hunt in battles against their enemies. The nerge served as a vital way for Genghis Khan to hone the skills of his soldiers and their leaders which would lead to success on the battlefield over and over again

Mongol Military Tactics and Techniques for Maneuver Warfare

“In the countries that have not yet been overrun by them, everyone spends the night afraid that they may appear there too.”

Ibn Al-Athir

The mobility of Genghis Khan’s troops has never been matched by other ground soldiery. He seems to have had an instinctive understanding that force is the product of mass and velocity. No other commander in history has been more aware of the fundamental importance of seizing and maintaining the initiative – of always attacking, even when the strategic mission was defensive.[21]

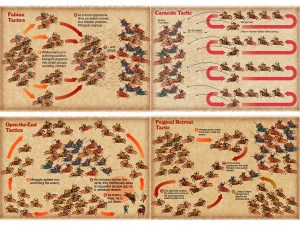

At the outset of a campaign, the Mongol toumans usually advanced rapidly on an extremely broad front, maintaining only courier contact between major elements. When an enemy force was found, it became the objective of all nearby Mongol units. Complete information concerning enemy location, strength and direction of movement was immediately transmitted to central headquarters, and in turn disseminated to all field units. If the enemy force was too small, it was dealt with promptly by the local commanders. If it was too large to be disposed of so readily, the main Mongol Army would rapidly concentrate behind an active cavalry screen. Frequently a rapid advance would overwhelm separate detachments of an enemy army before its concentration was complete.

Genghis and his able subordinates avoided stereotyped patterns of moving to combat. If the enemy’s location was definitely determined, they might lead the bulk of their forces to strike him in the rear or to turn his flank. Sometimes they would feign a retreat, only to return at the charge on fresh ponies.[22] The Russian army found itself quickly defeated when following a retreating Mongol force of lightly armed archers, only to find themselves enveloped in smoke from thousands of dung fires and set upon by heavy cavalry.[23]

Most frequently, however, the Mongols would advance behind their screen of light horsemen in several roughly parallel columns, spreading across a wide front. This permitted flexibility, particularly if the enemy was formidable, or if his exact location was not firmly determined. The column encountering the enemy’s main force would then hold or retire, depending upon the situation. Meanwhile the others would continue to advance, occupying the territory to the enemy’s flank and rear. This would usually cause him to fall back to protect his lines of communication. The Mongols would then close in to take advantage of any confusion or disorder in the enemy’s retirement. This was usually followed by eventual encirclement and destruction.

The cavalry squadrons, because of their precision, their concerted action, and their amazing mobility, were easily superior to all troops they encountered, even when these were more heavily armed or more numerous. The rapidity of the Mongol movements invariably gave them superiority offeree at the decisive point, the ultimate aim of all battle tactics. By seizing the initiative and exploiting their mobility to the utmost, the Mongol commanders operated inside their opponents’ decision cycle.

The battle formation was composed of five lines of horsemen, each in a single rank, with large intervals between each line. Heavy cavalry made up the first two lines, the other three being lighter horsemen. Reconnaissance and screening were carried out in front of these lines by other light cavalry units. As the opposing forces drew nearer to each other, the three rear ranks of light cavalry advanced through intervals in the two heavy lines to shower the enemy with a withering fire of well-aimed javelins and deadly arrows from their powerful longbows.[24]

The intensive firepower preparation would shake even the staunchest of foes. Sometimes this harassment would scatter the enemy without need for shock action. When the touman commander felt that the enemy had been sufficiently confused by the preparation, the light horsemen would be ordered to retire, and synchronized signals would start the heavy cavalry on its charge.

In addition to combining fire and movement – missile attack and shock action – the Mongols also emphasized diversions in all phases of combat. During the main engagement, a portion of the force usually held the enemy’s attention by frontal attack. While the enemy commander was thus diverted, the main body would maneuver to deliver a decisive blow on the flank or rear.[25]

To their enemies, the inexplicable coordination with which Mongol armies achieved their separate and common objectives was often astounding. Each carefully designed campaign was a masterpiece of original and imaginative strategy, and Mongol commanders could not have planned with as much breadth and daring as they did without absolute confidence in their communications. Through their simple signaling system, units could remain in immediate contact with each other along a wide front and through their unparalleled corps of couriers, armies hundreds of miles apart could remain under the tight control of one commander.[26] Tactical movements were controlled by black and white signal flags under the direction of squadron and regimental commanders. Thus there were no delays caused by poorly written orders or messages. The signal flags were particularly useful for coordinating the movements of units beyond the range of voice control. When signal flags could not be seen, either because of darkness or intervening terrain features, the Mongols used flaming arrows.[27]

In 1207, Genghis Khan and his army began an astonishing extension of Mongol military skill. Faced with the problem of laying siege to fortified garrisons in China, these wild cavalrymen of the plains, their competence as warriors honed in hunting and inter-tribal skirmishes, in wars full of movement, now settled to learn the long-drawn skills of siegecraft.[28] The resulting system for assaulting fortifications soon became virtually irresistible. An important element of this system was a large, but mobile, siege train with missile engines and other equipment carried in wagons and on pack animals. Genghis conscripted the best Chinese engineers to comprise the manpower of the siege train, and he adopted Chinese weapons, equipment, and techniques. Combining generous terms of service with threats of force, Genghis created an engineer corps at least as efficient as those of Alexander the Great and Caesar.[29]

Important cities and fortifications would usually be invested by one touman – supported by all or part of the engineer train – while the main force marched onward. Sometimes by strategy, ruse, or bold assault, the town would be stormed quickly. If this proved impossible, the besieging touman and the engineers began regular siege operations, while the main army sought out the enemy’s principal field forces. Once a Mongol victory had been achieved in the field, besieged towns and cities often surrendered without further resistance. In such cases, the inhabitants were treated with only moderate severity. But if the defenders of a city or fort were foolish enough to attempt to defy the besiegers, Genghis’ amazingly efficient engineers would soon create a breach in the walls, or prepare other methods for a successful assault by the dismounted toumans. Then the conquered city, its garrison, and its inhabitants would be subjected to the pillaging and destruction which have made the name of Genghis Khan one of the most feared in history.[30] Henceforth, every tribe of the Mongol army was required to assemble a siege train and practice how to employ it.

Genghis Khan’s genius as an organizer and as a strategical and tactical leader has probably never been excelled, and has been matched by few other generals in history. He utilized surprise, mobility, offensive action, concentrated force, and diversionary tactics to overwhelm armies which were usually more numerous, and frequently better armed.[31] His army’s terrifyingly swift and audacious use of mobility, coupled with diversionary tactics and surprise, made the Mongol army the greatest and most terrifying force the world had ever seen. Their superb application of the principles of maneuver warfare would conquer most of Asia, and would eventually threaten the European continent.

Note:

[1] B.H. Liddell Hart, Great Captains Unveiled (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 3.

[2] Ibid., 33-34.

[3] J. Lehnhof, “Genghis Khan,” 1998; available from http://www.qeocities.com/Athens/Forum/2532/paqe2.html; Internet; accessed 23 Feb 2000.

[4] Trevor Nevitt Dupuy, The Military Life of Genghis: Khan of Khans (New York: Franklin Watts, Inc., 1969), 6.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 7.

[7] Ibid., 8.

[8] Ibid., 9.

[9] Ibid., 16.

[10] David Nicolle, The Mongol Warlords (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 1990), 20.

[11] Dupuy, 18.

[12] Harold Lamb, Genghis Khan. The Emperor of All Men (New York: Garden City Publishing, Inc., 1927), 76.

[13] James Chambers, The Devil’s Horsemen, The Mongol Invasion of Europe (New York: Atheneum, 1979), 51.

[14] Per Inge Oestmoen, “The Mongol Military Might,” 29 September 1999; available from http://home.powertech.no/pioe/monmight.htm; Internet; accessed 23 Feb 2000.

[15] Dupuy, 20.

[16] Oestmoen

[17] Peter Brent, The Mongol Empire (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1976), 31.

[18] Dupuy, 21.

[19] Nicolle, 37.

[20] Chambers, 60.

[21] R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993), 367-373.

[22] Dupuy and Dupuy, 369.

[23] Jonathon D. Bashford, “The Mongols,” Feb 1997; available from http://library.thinkquest.org/11847/qather/9b.html; Internet; accessed 23 Feb 2000.

[24] Dupuy and Dupuy, 370.

[25] Ibid., 370.

[26] Chambers, 61.

[27] Dupuy and Dupuy, 372.

[28] Brent, 48-51.

[29] Dupuy, 40.

[30] Ibid., 40-41.

[31] Ibid., 26.

Autore: Joe E. Ramirez Jr.

Fonte: Defense Technical Information Center – (DTIC)

Lascia un commento