The phrase ‘military strategy’ in this article’s title might be a tautology for some, as strategy originally concerned the art or skills of the general.1 However, today, strategy is applied across almost all areas of society with the field of business strategy arguably more vibrant than that of contemporary military strategy. Given such common usage, adding an adjective to ‘strategy’ is now essential to aid comprehension. Adding an adjective has also become necessary as the idea of grand strategy has become more widely used.2

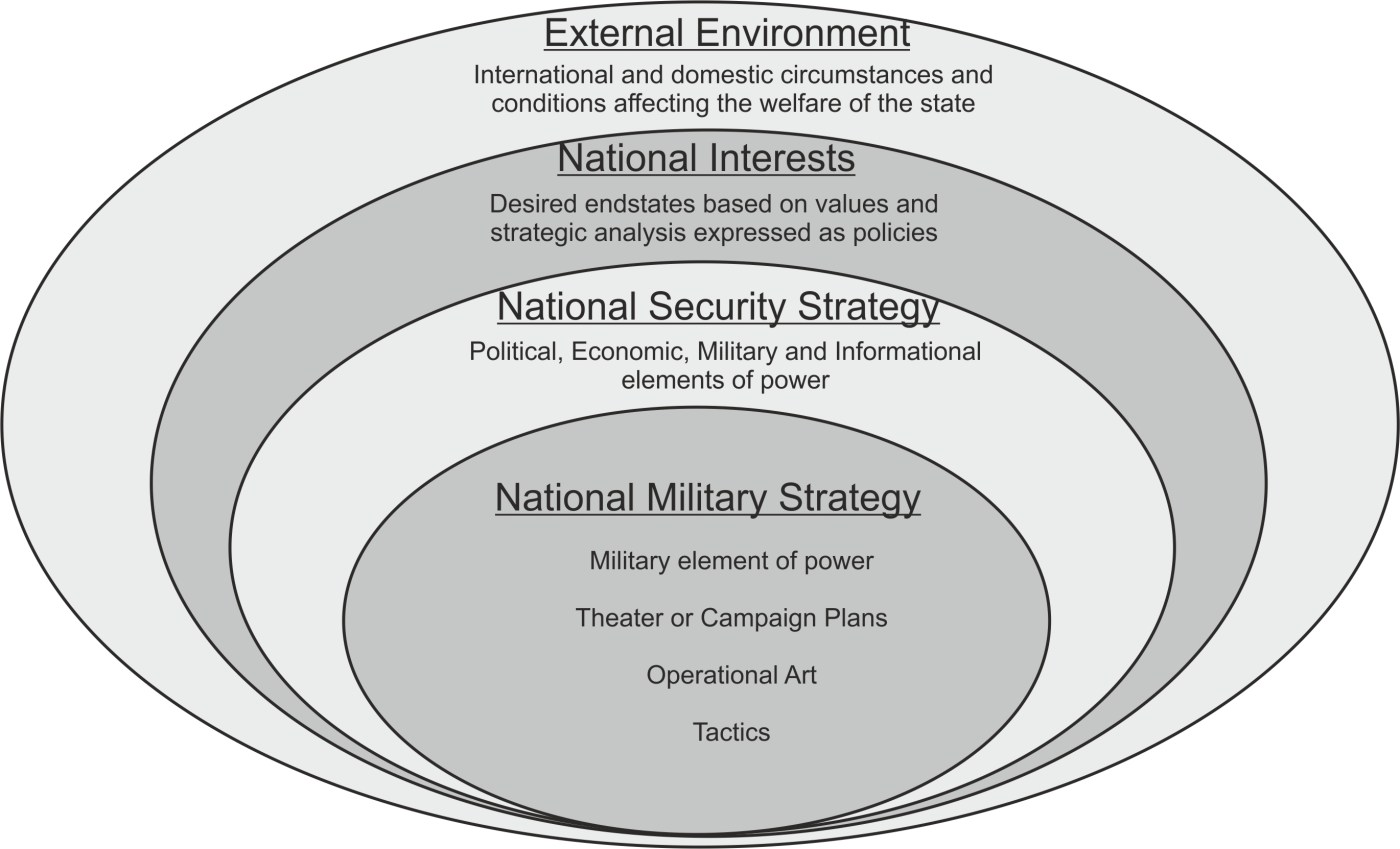

Grand strategy is conceived as sitting hierarchically above various subordinate strategies that it informs and integrates. These subordinate strategies are frequently titled using Harold Laswell’s fourfold division of a nation’s major instruments of national power into diplomatic, information, military and economic (DIME).3 This is the basis both of the well-known DIME acronym used at defence staff colleges worldwide, and of diplomatic strategy, information strategy, military strategy and economic strategy being regularly used terms.

This article focuses on the idea of military strategy. The first section discusses four fundamental characteristics of military strategy and the second applies these to Operation Iceberg, the capture of Okinawa in the largest joint operation in the Pacific during the Second World War. This historical case of almost 80 years ago involved American forces in a great power war against a major north-east Asian nation. The strategic-level experiences of that time may have some resonances in contemporary strategic thinking about worst-case, regional contingencies.

Four fundamental characteristics

Strategy is simply a methodology able to be used to solve specific types of problems. These are problems where an objective – an endpoint – can be defined. The strategy adopted may not succeed, but the intention is to try to achieve this desired outcome. Western thinking since Carl von Clausewitz has stressed military force is used to achieve political outcomes; ‘the political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it’.4 Taking action to achieve a defined endpoint is the first fundamental characteristic of military strategy.

The objective in a strategy (as specifically relates to armed conflict) is accordingly best expressed in terms of politics. The field of politics between states has been examined for decades within the academic discipline of international relations (IR). Its language, concepts and theories, developed over many years, can be used to assist defining strategic ends.

There was an important modifier articulated by British strategist Basil Liddell-Hart, who held that the aim of war should be a better peace.5 The political object is not just the return to the status quo ante, as this led to the war in the first place. Military strategy should seek the peace beyond, not the war in itself. Clausewitz noted: ‘The political object.. .will thus determine.. .the military objective to be reached.’6

In recent years, Western states have had great difficulty in defining the desired endpoints of the various conflicts entered into in the greater Middle East. However, strategy is an inappropriate problem-solving methodology if the objective cannot be defined with sufficient clarity to guide military actions. In such circumstances, better approaches may be those that respond to events and do not try to shape the future.

An example is risk management, which tries to limit losses to an acceptable level if some specific feared threat eventuates. This is the logic underlying the views that perceive defence forces as insurance policies to be ‘cashed in’ if national security is seriously threatened. Another approach is opportunism: where states take advantage of events, exploiting sudden windows of opportunity that open. Both approaches are valid if ends cannot be reasonably defined. In this, they both require having the right means available at the right time to be able to adequately respond when called.

To illustrate with a contemporary case, a strategy might be an appropriate approach to defeat a specific terrorist group like Islamic State; sensible ‘ends’ could be devised. Terrorism in general though cannot be addressed using strategy. Terrorism is a tactic any hostile non-state group could potentially use in the future and so specificity in ends sought is impossible. Risk management – that is trying to diminish the impact terrorism might have at some future time – becomes a more sensible approach to adopt.

In this, the desired endpoint depends on the context. As the old maxim declares: the enemy gets a vote. This highlights the second fundamental characteristic of military strategy: it involves interacting with intelligent and adaptive others, whether friends, neutrals or adversaries. This social interaction, however, is of a particular kind.

Each party involved continuously modifies their position, intent and actions based on the perceptions and actions of the others participating. These interactions ‘are essentially bargaining situations…in which the ability of one participant to gain his ends is dependent …on the choices or decisions the other participant will make.’7

In operation, a strategy constantly evolves in response to the other actors, each implementing their own countervailing or supportive strategies. Edward Luttwak termed this ‘the paradoxical logic of strategy’, where successful actions cannot be repeated as the other party adapts in response to ensure the same outcome cannot be gained in this way again.8 Strategy is simply a particular form of interactive social activity where victory comes from bargaining with those involved.

This attribute reveals the difference between a strategy and a plan. The objects of a strategy actively try to implement their own strategies, changing and evolving as necessary to thwart efforts made to impede them. In a strategy, all involved are actively seeking their own ends. In contrast, in a plan all involved are working towards the same objective; they do not have their own countervailing goals. Plans are not ‘essentially bargaining situations’.

And so, to the third fundamental characteristic of military strategy: it is just an idea. In an oft-used model, Art Lykke deconstructed the art of strategy into ends, ways and means where the ‘ends’ are the objectives, the ‘ways’ are the courses of actions and the ‘means’ are the instruments of national power (in this article in the form of military power).9 The ‘means’ are used in certain ‘ways’ to achieve specific ‘ends’. All three parts are important; yet some people err in trying to simplify this even further.

Some conceive of strategy as being solely a balance between ends and means. Some declare: ‘strategy is simple: it is the process by which a state matches ends to means.’10 In the industrial era then, victory would be assured through fielding greater mechanised forces. In today’s information technology era, victory would go to the actor fielding greater information technology (to get inside other’s OODA loops no less).11 In this perspective, great means leads directly to great victories.

Historically, nations with great means have often found it surprisingly difficult to convert these into achieving their desired ends.12 Given its great means, the US should have been readily able to achieve its objectives in Afghanistan after 2001, in Iraq after 2003 or in the 1960–70s in South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The poor outcomes actually achieved suggest strategy is more than the simple balancing of ends and means. The ways also need deep consideration. Sir Lawrence Freedman nicely phrases this in observing that strategy is ‘about getting more out of a situation than the starting balance of power would suggest’. 13

Good strategy involves an astute course of action, a shrewd ‘way’, that is additive to the available power; the impact of the means is then magnified. In contrast, poor strategy subtracts from the available means; it destroys the power you have. This might all be simplified into Ends = Ways + Means, albeit it is essential to recall the inherent impossibility of actually summing unlike objects.

The formula highlights that if a strategy fails it may not be solely due to inadequate means; there could be shortcomings in the ways the means are used as well. If the means are meagre, the ends may still be achievable through using the means in clever ways without needing to adjust the ends downwards. Freedman continues: underdog strategies, in situations where the starting balance of power would predict defeat, provide the real tests of creativity. Such strategies often look to the possibility of success through the application of a superior intelligence which takes advantage of the boring, ponderous, muscle-bound approach by those who take their superior resources for granted.14

Strategy is the ways in Lykke’s formula. It sets out the causal path to victory. Strategy explains how the means will be used in terms of how this leads to the defined political objective. Strategy is an idea but one with a defined purpose.

The final characteristic is often neglected: military strategies have a finite life. There is sometimes a perception that strategies are simply set-and-forget, which once started continue unchanged for an indefinite but protracted period. This is a serious misunderstanding; strategies should remain dynamic throughout their life.

A strategy fundamentally involves interacting with intelligent others, all seeking their own objectives. A strategy as first conceived will inevitably decline in effectiveness and efficiency over time as others take actions that oppose it, either deliberately or unintentionally. Moreover, the complex environment within which strategies operate remains continually evolving and changing.

Strategies should be continually adjusted to meet the ever-changing circumstances. In this way, they then have a distinct life cycle: strategies arise, are purposefully evolved through learning and then at some point finish. A strategy may finish when it reaches its desired objective, although an earlier termination may be as likely given a strategy is characterised by interaction with intelligent and adaptive others. Minor adjustments can only go so far to address steadily changing situations and eventually the extant strategy may reach a point at which its utility is less than its costs.15

Clausewitz’s notion of a culminating point captures this idea.16 At some time in its life cycle a strategy will reach a culminating point where it has achieved the greatest effect for the effort expended. Beyond this point, greater efforts will yield diminishing effects and bring only marginally greater benefits.

There are two broad alternatives when a strategy reaches its culminating point. The strategy may be terminated, with a careful transition to a replacement strategy or some other approach. Conversely, the strategy may be continued if there are reasonable expectations it will still achieve the desired objectives. The focus may then move to optimising the strategy’s effectiveness and efficiency to shift its culminating point further into the future.

Operation Iceberg: capturing Okinawa

The four fundamental characteristics of military strategy – having defined ends, interdependent interaction between those involved, being simply an idea and having a life cycle – can be further appreciated in a case of military strategy in practice: the three-month operation from April to June 1945 to capture from Japan the island of Okinawa in the Ryukyu Island chain south of the Japanese home islands. The possibility of such an operation had been a feature of American war plans since 1906.

When the Russo-Japanese war (1904–06) ended, President Theodore Roosevelt inaugurated what became War Plan Orange, a contingency plan for a future American war against Japan. Plan Orange went through many iterations as the context evolved, Japanese force structure changed and new technologies emerged. Even so, the basic military strategy remained the same: pushing across the central Pacific, capturing various well-placed islands as fleet bases, including in the Ryukyu Island chain, and culminating in severing Japan’s sea lines of communications. A negotiated peace was then assumed to shortly follow.

This was a military strategy of unlimited economic war where the US Navy would strangle Japan, bringing about ‘complete commercial isolation’ and leading to ‘eventual impoverishment and exhaustion.’ There are echoes here of Operation Anaconda during the American Civil War (1861–65) when the USN strangled Confederate merchant ship trade. This was unsurprising as in 1906 that was the big war that USN planners remembered and looked back to for guidance.17

The military strategy was continually refined in numerous war games, gradually being incorporated into the USN’s and US Marine Corps’ (USMC) strategic culture. Military capability and capacity development was driven by the demands of the envisaged transoceanic strategy, particularly in terms of developing a fleet supply train, including refuelling at sea. Major General Ben Hodge, Commander of the XXIV Army Corps at Okinawa, referred to the battle as ‘90% logistics and 10% fighting.’18

Of equal import was the USMC’s concentration on developing the tactical expertise, doctrine and technology for opposed landings; in the interwar period this focus was unique amongst major powers.19

When the Plan was eventually implemented after the December 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, to a considerable extent the US armed forces simply needed expanding; albeit, Japan was a clever enemy and the military strategy needed constant adjustment. Admiral Chester Nimitz, for the invasion the Commander-In-Chief Pacific Fleet, famously stated that the war unfolded just as the Plan Orange war games had predicted.20 This might be overstating matters a little in the specific case of the invasion of Okinawa.

The USN was surprised by the Kamikazes, the manned forerunner of the modern anti-ship missile, which sank more than 30 ships and damaged another 350 or so. For the time, USN warships had leading-edge air defence technologies that were highly effective but the Japanese counter to them was simply unimaginable to pre-war planners. Moreover, the logistics supply train was stretched to the limit because of conflicting demands elsewhere in the Pacific and Europe. Some consider the consequent supply shortages contributed to the battle being protracted, with subsequently high US causalities.

The US Army and USMC land force units were similarly surprised that Japanese forces adopted a military strategy of defence-in-depth rather than the previously employed military strategy of beachhead defence, which included ‘bamboo spear’ tactics and nocturnal Banzai charges.21 Japan had learned from earlier battles and inflicted many more casualties on attacking US military forces than previously. On the other hand, Japanese forces were surprised that US land forces rarely attacked at night, as the Japanese found this hard to counter.22

At the higher strategic level, matters were somewhat more confused. The USN focused on implementing Plan Orange even though it was without a compelling causal path to explain how Japan losing control of the sea would necessarily lead to victory. Regardless, the Okinawa invasion by the USN submarine fleet combined with airborne mining and maritime air attacks had already achieved the required sea dominance. While the original pre-war strategy called for the Ryukyu Islands to be taken, technological developments now made the invasion unnecessary if the original economic strangulation ‘way’ was still sought. In the Navy’s defence however, the war plans assumed that strangling Japan would lead to a negotiated peace – not an unconditional surrender – and only after a long while.23

The US Army’s way to gain victory was based upon a large-scale land battle to defeat the Japanese Army on the Tokyo plains, impose their will upon the enemy and achieve an unconditional surrender. Clausewitzian in approach, the Japanese Imperial Army thought the same – except they would win the large-scale battle, and the American public would lose interest and give up. The US Army did need the Ryukyu Islands captured in order to turn them into a forward mounting base to support such a way. The problem was that this was now anticipated to possibly cost between 1.7 and 4 million American casualties including 400,000 to 800,000 killed, and 5 to 10 million Japanese deaths. Many Americans, including the President, lacked enthusiasm for this.24

The US Army Air Force’s (USAAF) ‘way’ to gain victory was different again. Air power would destroy Japan’s ability and will to resist. By the Okinawa invasion the USAAF was undertaking large-scale city raids, having to divert bombers from this to provide tactical support for Operation Iceberg. The USAAF did not need the Ryukyu Islands captured for their way.25 The USAAF way was no easy path to victory. American and Japanese studies estimated some 500,000 Japanese died (including the two atomic attacks) although there is robust disagreement over totals.

In the end, two atomic bombs made a Japanese home island invasion unnecessary.26 They addressed the Plan Orange strategy’s defect of how to translate maritime trade strangulation into a quick surrender. At least, the Japanese emperor believed the bombs were decisive. In his speech to the Japanese people, he declared that the: ‘cruel bombs … kill and maim extremely large numbers … To continue the war further could lead in the end to … the extermination of our race … [surrendering] would open the way for a great peace’.27

Even so, Operation Iceberg killed 12,000 Americans, 110,000 Japanese military and around 100,000 Okinawans (mostly civilian). The invasion was necessary for victory only if the US Army’s way was followed.

On the other hand, some argue that such losses made clear to American military and political leaders that invading the home islands would be a most difficult operation. The benefits of unconditional surrender – like that achieved in Europe against Germany halfway through Operation Iceberg – started to look less appealing when weighed against the potential costs. A negotiated peace became more attractive, and this was explicitly offered in the Potsdam Deceleration on 26 July 1945, which included a subtle implication that the emperor might be retained.28

The four fundamental characteristics of military strategy were discussed earlier: defined ends; interdependent interaction between all involved; being simply an idea, the ‘ways’ in ‘ends, ways and means’; and having a lifecycle where strategy arises, evolves through learning and finishes.

While Plan Orange outlined the way Japan would be defeated, it was vague about the better peace that would result. There were no thoughts of dismemberment, rather a more fuzzy understanding that the negotiated victory would reintegrate a now-peaceful Japan into the regional economic system. By the time the Pacific War started though, America and Great Britain had agreed in the 1941 Atlantic Charter to a relatively well-defined better peace that would result.

In the language of IR, this was a vision of an institutionalised peace that bought order, prosperity and legitimacy.29 Similar to today’s rules-based order, ‘better peace’, the institutionalised peace sought in the Second World War was different because it was built around people being free to decide their governments themselves. In contrast, the rules-based order advocated today considers authoritarian states as equal to democracies in the establishment and application of the rules.

War Plan Orange was weak on what happened in the endgame, which partly explains why the US Navy, Army and Army Air Force drifted into seemingly fighting separate wars albeit assisting each other as needed. The military strategic ends were not closely integrated with the ways and as American forces neared Japan this became progressively more troublesome.

The accidental atomic victory proved congruent with the desired ends. The Plan Orange military strategy was now replaced by another different strategy, which aimed to guide Japan’s recovery from the war towards mutually acceptable outcomes.30 The Plan Orange military strategy finished with the military victory over Japan but there was another strategy waiting in the wings to replace it.31

The other characteristics of military strategy can be appreciated in this discussion: the strategy evolved under wartime demands; the strategies in play were simply ideas, as Plan Orange ran out of steam and its lack of a compelling causal path to victory became apparent there were several competing ideas, and finally the Plan Orange strategy had a definite lifecycle: it finished and was replaced.

Military strategy is an intellectual tool to solve certain types of problems – but not all. The four fundamental characteristics discussed provide the bare bones on which to build. Making military strategy is important and consequential in times of both peace and war, as Operation Iceberg revealed. Moreover, it drives defence force development, doctrine and tactics. As Clausewitz realised, military strategy is fundamental to victory, the ultimate purpose of a nation’s armed forces.

Note:

1 Beatrice Heuser, The Evolution of Strategy: Thinking War from Antiquity to the Present, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, p 4.

2 Peter Layton, ‘The idea of grand strategy’, The RUSI Journal, 2012, 157(4):56–61.

3 Harold D Lasswell, Politics: Who Gets What, When, How, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1958, pp 204–05

4 Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Michael Howard and Peter Paret eds trans), Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1984, p 605.

5 B H Liddell-Hart, On Strategy, 2nd rev edn, Faber and Faber, London, 1967, p 338.

6 Clausewitz, On War, p 81

7 Thomas C Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict, A Galaxy Book, Oxford University Press, New York, 1963, p 5.

8 Edward N Luttwak, Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace, Belknap Press, Cambridge, 1987, pp 7–65

9 Jr. Arthur F. Lykke (ed), Military Strategy: Theory and Application; US Army War College, Carlisle, 1989, pp 3–9. Harry R Yarger, ‘Toward a Theory of Strategy: Art Lykke and the Army War College Strategy Model’, in J Boone Bartholomees Jr (ed), US Army War College Guide to National Security Policy and Strategy, 2nd ed, Carlisle Barracks: Strategic Studies Institute, June 2006, pp 44–45.

10 Christopher Layne, ‘Rethinking American grand strategy: hegemony or balance of power in the twenty-first century?’, World Policy Journal, Summer 1998, 15(2):8.

11 OODA is an acronym for Observe-Orient-Decide-Act devised by John Boyd. See: Chet Richards, ‘Boyd’s OODA Loop’, Necesse, 2020, 5(1):142–165.

12 Critics of this power-as-resources model decry this as a ‘vehicle fallacy’. David Macdonald, ‘The power of ideas in international relations’, in Nadine Godehardt and Dirk Nabers (eds), Regional Powers and Regional Orders, Routledge, Abingdon, 2011, p 34.

13 Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: A History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013, p xii.

14 Freedman, Strategy: A History.

15 A strategy may though also reach such a point of diminishing returns because of poor implementation not just due to the original conception losing effectiveness.

16 For Clausewitz, an offensive strategy continued until it could no longer advance and then the strategy needed to transition to the defensive. Clausewitz, On War, p 528

17 Edward S Miller, War Plan Orange: The US Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1991, p 28.

18 Major General Ben Hodge, 12 April 1945, Interview with LTC Stevens, Army Historical Division, National Archives College Park

19 Williamson Murray and Alan R. Millet (eds), Military Innovation in the Interwar Period, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1996, p 59.

20 Miller, War Plan Orange, p 2.

21 G Vance Corbett, Operation Iceberg: Campaigning In The Ryukyus, Naval War College, Newport, 1998, p 10.

22 Corbett, Operation Iceberg, p 22.

23 Miller, War Plan Orange, pp 366–368.

24 Figures from a study undertaken for Secretary of War Henry Stimson. See: Richard B Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire, Random House, New York, 1999, p 5.

25 Haywood S Hasell, Strategic Air War Against Japan, Air War College, Alabama, 1980, p 91. 26 An alternative view is given in Hibiki Yamaguchi, Fumihiko Yoshida and Radomir Compel, ‘Can the Atomic Bombings on Japan Be Justified? A Conversation with Dr. Tsuyoshi Hasegawa’, Journal for Peace and Nuclear Disarmament, 2019, 2(1):19–33.

27 Emperor Hirohito’s speech of 15 August 1945 quoted in John W Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Aftermath of World War II, Penguin Books, London, 1999, p 36

28 Akira Iriye, Power and Culture: The Japanese–American War 1941–1945, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1981, pp 248–264.

29 Elizabeth Borgwardt, A New Deal for the World: America’s Vision for Human Rights, Belknap Press, Cambridge, 2005, p 5

30 Iriye, Power and Culture, pp 266–267.

31 John W Dower, Embracing Defeat, pp 65–84

Autore: Layton, Peter. “Military Strategy Fundamentals.” Australian Journal of Defence and Strategic Studies 4, no. 1 (June 2022): 105–114, https://doi.org/10.51174/AJDSS.0401/JTYZ5777.

Fonte: Australian Journal of Defence and Strategic Studies

Categorie

Tags

Lascia un commento