Ancient China and Rome have often been subject to intense comparison as the cultural

forerunners of East Asian and Western civilizations. This comparison is made especially with the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), the contemporaneous government of China during much of the Roman Empire’s reign over Europe. However, if one looks back at the foundations of the first Chinese imperial dynasty, the Qin, one can find numerous similarities between the Qin state’s conquest of China and the reunification of the Roman Empire during the crisis of the third century. One can analyze the two states as they adapted to threats from within and outside their territories and reformed themselves to match the challenges of their times. These changes, primarily military and governmental reforms, allowed both states to conquer and assimilate their enemies rapidly.

This paper will examine these reforms and their effects to understand better how governance and statecraft can lead to military success.

The Qin’s wars of unification help to explain the comparison between pre-unification Qin

and third century Rome. In particular, it is similar to Rome’s restoration of the imperial borderlands at the end of the crisis of the third century. For one, the unification of China and the reunification of the Roman Empire both occurred during the ancient period. This makes the sophistication of their military equipment comparable, as both states would primarily use infantry armies armed with hand-to-hand weapons. Second, both conquests occurred within a similar timeframe, as the Qin conquered China within nine years, and Rome reunified the empire within four.

These short timeframes allow for a more focused examination of the inner workings of each empire’s government. Finally, both unifications primarily occurred as military conquests of other states. One might argue that Qin’s rise to power would be more comparable to the initial rise of the Roman empire, however, this comparison would be less accurate. While the Qin would conquer China in less than a decade, the Roman Empire grew slowly over many centuries and as such Rome’s smaller conquest of its political rivals at the end of the crisis of the third century is far more analogous to the Qin experience.

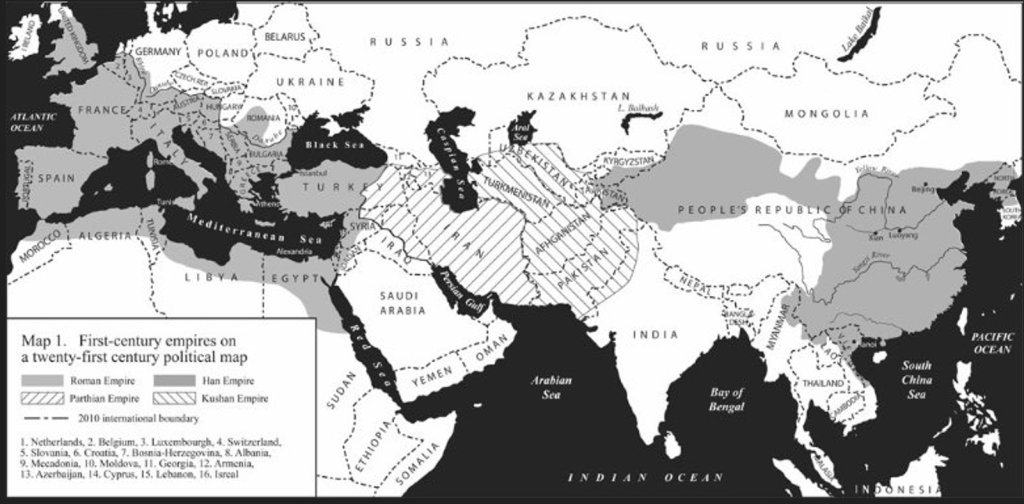

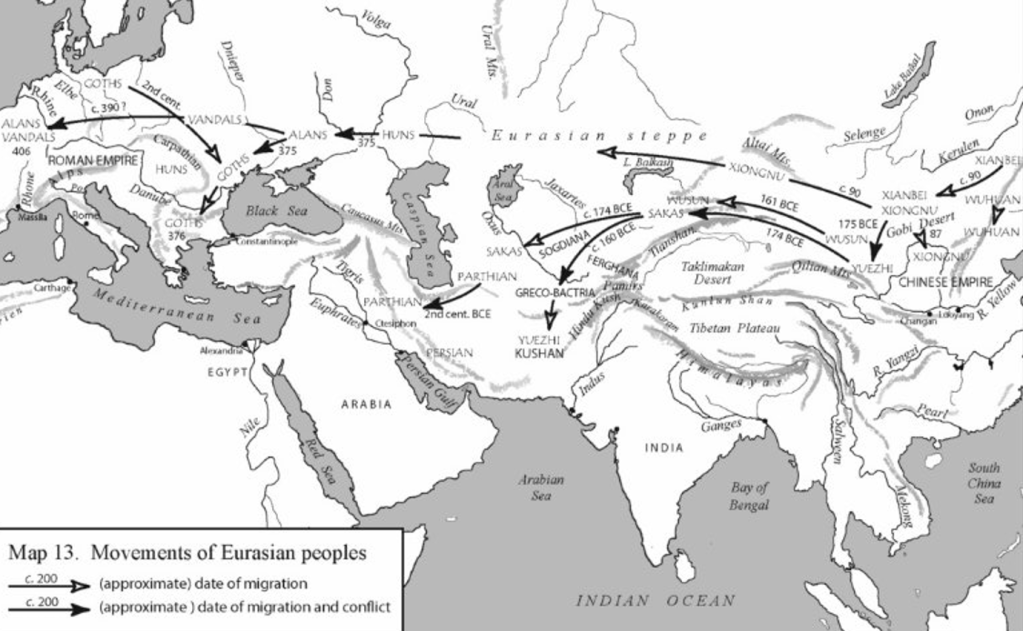

Before examining their comparable governance, it is crucial to first understand the background of the Qin and Rome conquest. The Qin polity found itself at odds with many other regional states for dominance, particularly the Qi and Chu, the two other major forces in China at this time. The Qin were situated at the edge of the Chinese civilization, in the mountainous area west of the Central Plains, with nomadic steppes to its north and competing Chinese states to its east.[1] During this period, the Qin found themselves in the final stages of the iron age and therefore had access to large quantities of high-quality iron weapons for their armies. Wu Qi (440–381 BCE), a prominent military leader and philosopher from the Chu state, described the Qin as follows: “The people of Qin are ferocious by nature and their terrain is treacherous. The government’s decrees are strict and impartial. The rewards and punishments are clear. Qin soldiers are brave and high in morale.”[2] Wu Qi’s words, written far before the First Emperor’s reign, clearly show that their disciplined and warlike nature made the Qin a serious threat to their foreign rivals; these traits would eventually allow them to assume a dominant position within China. However, they were not yet able to face the combined armies of other states.

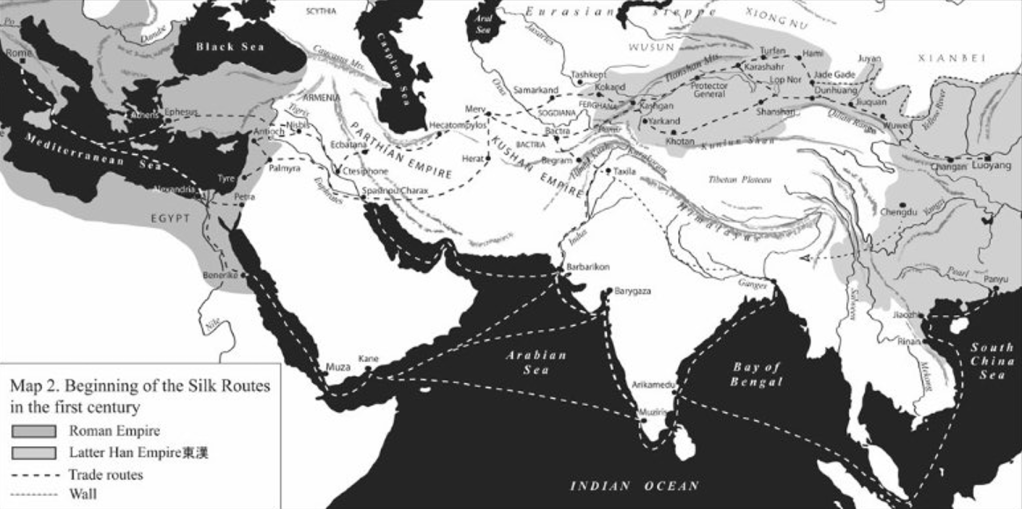

Therefore, the Qin created pragmatic alliances to maintain good relations with distant states while engaging in wars against their neighbors. This system, detailed in the Thirty-Six Stratagems in the 2nd or 3rd Century BCE, showed that Qin was sensitive to the geopolitical realities of its region and had responded well to its limitations.[3] This strategy made their enemies divided, which allowed for the Qin to defeat them during the final wars of unification under the First Emperor (r. 247 – 210 BCE).

In the case of the Roman Empire, their position was one of instability and division. After

the assassination of the last emperor of the Severan dynasty (193 – 235 CE), the empire underwent continuous usurpations, revolts, and invasions, known as the crisis of the third century.[4] This situation led to the disintegration of the empire into three smaller states: the Gallic Empire, which centered on the province of Gaul and encompassing much of modern-day France and England, the Palmyrene Empire, based out of the city-state of Palmyra in modern-day Syria and encompassing Egypt, the Levant, and a significant portion of Anatolia, and the reduced continuation of the Roman Empire, centered on the city of Rome itself and which held the regions of Iberia, Italy, Greece, and North Africa. Although reduced, the original imperial state retained control over some of the most productive parts of the Empire, making it incredibly powerful militarily and paralleling the strength of the Qin at this time. However, like the Qin, they were vulnerable if attacked by multiple enemies at once.

The Romans had already experienced this during the crisis, as uprisings along the Danube River and invasions in Gaul and the Levant were the original cause of the empire breaking apart. In order to not be overwhelmed, the Romans, under Aurelian (r. 270 – 275 CE), focused on a single threat at a time. Through this strategy, Aurelian would defeat usurpers, barbarian invasions, the Palmyrene Empire, and the Gallic Empire without being overrun. Much like the system contained in Thirty-Six Stratagems Aurelian attempted never to face more than one enemy

at once. While outside threats were grave, the Romans faced their greatest threat from the usurpersthat prevented lasting stability within the empire and perpetuated a constant state of civil war.

Aurelian managed to reestablished legitimacy by retaking the lost lands of the empire through

conquest. As Edward Gibbon writes, “Aurelian…triumphed over the foreign and domestic enemies of the State, re-established, with the military discipline, the strength of the frontiers, and deserved the glorious title of Restorers of the Roman world.”[5] Aurelian’s Roman Empire inherited a military that his predecessors had already reformed in response to the threats of the crisis. ForRome, the importance of military strength helped to maintain internal stability. The emperor needed a loyal military that was large enough to deter rivals within the state and reassure the provinces that he could defend them against the “barbarians” at the borderlands. This protectorate relationship with the provinces had granted Rome legitimacy before the crisis of the third century had begun. However, Rome lost this relationship once it could not defend them from their enemies.

Afterwards, more rebellious figures revolted, which began in the border provinces via insurrections. In response to this threat, former emperor Gallienus created a rapid response cavalry force mobile enough to respond quickly to threats in any particular region, as well as large enough to intimidate threats both foreign and domestic.[6] Aurelian also benefitted from another of Gallienus’s reforms: the end of political appointments to the military. Before the reform, it had been common for upper-class families and politicians to be assigned to military roles without formal training. The elimination of this practice occurred via separating the Senate from the military. This move both created a more meritocratic system in which the best soldiers would be promoted to higher command, while simultaneously removing the Senate’s connections to the army, weakening their ability to foment rebellions.

The First Qin Emperor also benefited much from his predecessors’ policies. His predecessors had conquered vast amounts of territory and adopted the most advanced military technology. Additionally, their use of a meritocratic system allowed for the most skilled to rise within the ranks, as seen with Wang Jian and Bai Qi. To take Wang Jian, the primary military leader during the unification, as an example, he commanded offensives into the Chu state on a scale that would not be replicated in Europe until the late medieval era. A meritocratic system ensured generals like Wang Jian would have military competency and provided the drive to be romoted and rewarded for victories. While Sima Qian might say that leaders like Wang Jian andBai Qi had “something short about them”[7] due to their character, there is no doubt that Qin would have been unable to have the success they did without their skills in battle. This also monstrates the Emperor’s ability to command vast scores of soldiers during a period in which communication and logistics were still largely in their infancy. As written by Sima Qian, Wang Jian requested 600,000 soldiers for the conquest of Chu, and this request was filled without argument by the First Emperor.[8] For most ancient societies, an army of this size would have been incredibly costly and difficult to raise, exemplifying the strength of the Qin government in supporting a force of this size.

Looking to Qin’s government, one can describe it as broadly authoritarian, which helped

to create internal discipline that served the armies in their conquest. An example of this

authoritarianism were the legalist reforms that came to the forefront of Chinese political culture during the Qin period. One scholar from Shandong University describes these reforms as “geared for persistent war, conquest, and the bureaucratic redefinition of an expansive domain.”[9] This was most visible in Shang Yang’s reforms which increased government control over citizens, as detailed in the Book of Shang Yang. During his tenure as the chancellor of Qin, Yang strengthened the Qin’s military position by increasing government regulation over the populace. This occurred via breaking traditional community structures and fully linking the traditionally agricultural economy to the military.[10] Yang’s tenure led to a significant increase of central government control of the state and this occurred by increasing the state’s military power. The purpose of these government reforms had been to make the state more efficient, which helped the state to improve its ability to wage war.

Likewise, the Roman Empire changed significantly during the crisis of the third century as

the previous system of the Empire, the Principate, was insufficient to face the challenges of a

Rome in decline. This resulted in the Dominate, a more autocratic, modernized Roman state.

Where previously the Empire retained many of the trappings of republicanism, the new Roman

state became more autocratic and hostile towards competing internal power structures. This led to the end of the Senate’s connection to the military and the formation of an imperial bureaucracy.

Emperor Gallienus had begun these changes by curtailing the role of the Senate in a process that could be described as proto-absolutist. The Roman Senate was later excluded from military

command, as well as the majority of provincial governorships. Instead, the military apparatus

became professionalized, with merit triggering promotion rather than political connections.

Subsequently, this led to further exclusion of the Senate from governing, as many provinces were transitioned to imperially appointed governors rather than senatorial rule.[11] This promoted the loyalty of the provinces during times of strife and further separated the Senate (and therefore the elite) from real political power. Roman politics became more and more irrelevant as power shifted from emperor to emperor, with the Senate as little more than an afterthought. This curtailing of the Senate led to the creation of a bureaucracy, as the elites no longer participated in the governance of the empire. The emperor created a separate bureaucracy of administrators that replaced senators, and these bureaucrats reported directly to the imperial office.

The Qin experienced comparable changes as they conquered their neighboring states, as

the government and military were often led by commoners who were rewarded with lands after

they had won victories. This famously occurred with Shang Yang, who was rewarded with a large

fief after the conquest of Wei. Likewise, Wang Jian received numerous rewards from the First

Emperor as he led Qin’s armies in the conquest of Chu. Following their conquest, the Qin

integrated new lands into a centralized state bureaucracy, much like the Romans following the

reconquest of their lost provinces.[12] The meritocratic character of both Rome and Qin allowed for both civilizations to have gains in strength, as the ambitious and talented received promotions and rewards, while those that failed would be quickly replaced.

Furthermore, both conquests also had similar legacies. Both Aurelian and the First Emperor

retained reputations for cruelty that endured far beyond their reigns. For the First Emperor, the

nature of fighting many wars would explain this, but a large part of the residual hostility is due to

the harsh rulership the Qin employed. Jia Yi (c. 200 – 169 BCE) was a writer and politician of the

early Han dynasty, and he characterized the First Emperor harshly in his work Transgressions of the Qin: “[The First Emperor] cast aside the kingly Way and relied on private procedures,

outlawing books and writings, making the laws and penalties much harsher, putting deceit and

force first and humanity and righteousness last, leading the whole world in violence and cruelty.”[13]

This general dislike of the First Emperor was shown following his death as the Qin Dynasty was

quickly overthrown by an uprising of separatists and usurpers. Jia Yi placed the blame for the fallof the Qin at the feet of the First Emperor as a result of his governance being too cruel.

Aurelian experienced a similar hostility during his reign, as his zeal for reform led to an attempt to remake the Roman monetary system and purge the corruption that was slowly suffocating the economy. This took the form of a new system of coinage and greater oversight over the mints to prevent illegal debasement, much to the dismay of mint employees, leading to their eventual revolt.

While this revolt would be put down at great cost in lives Aurelian’s severe reputation would eventually cause his death as his officers erroneously feared they would be purged and killed him out of their own self-interest.[14] Following his death, the Senate would “secretly rejoice” Aurelian’s assassination, likely due to the repression of the senatorial class during his reign.[15] Just as the senators rejoiced Aurelian’s death, the scholars of Qin rejoiced in the death of the First Emperor, who had oppressed them in the name of stability.[16]

However, it remains undeniable that these rulers caused a great impact on the world during their reigns, and it is part of their nature as historical figures to be complex.

When discussing similarities between the two states, it is also important to discuss the unique aspects of each state during these events. In comparison to the Qin’s establishment of the

first centralized Chinese empire, the task completed by the Romans is on a significantly smaller

scale. They were reconquering lost lands, while the Qin had the challenge of acquiring and

maintaining control over vast swaths of new lands and the people that lived there. The challenge

presented to the Qin is also visible in the number of enemies each state faced. While both Rome

and Qin faced threats on multiple fronts, the Qin faced six major states, while Rome only faced

two. This is also supported by the scale of the wars that were fought. As mentioned previously,

Wang Jian had requested 600,000 men for the conquest of the Chu, while the number of Romans involved in the campaign against the Palmyrene Empire was likely one-third of this massive force.[17] The difference in the scale of these conquests bestows immense respect to the Qin for achieving what they did, especially as Rome was considered the preeminent masters of logistics in Europe during the ancient period.

In guiding their states, the First Emperor and Aurelian led the Qin and Rome to newfrontiers and renewal, respectively. Aurelian restabilized the empire after decades of decay, and the First Emperor created the first centralized Chinese empire. This was done through great efforts by these leaders and their predecessors to reform and innovate both their governments and militaries to face new challenges. Without these reforms, neither Aurelian’s campaigns nor

the Qin’s wars of unification would have been possible.

While differences between the Qin and Rome remain, the study of these two societies helps to show the effect of centralizing autocracy and meritocracy on the power of states militarily. As a result of the goals set by their leaders, both states became significantly more autocratic, and this provided the government with the authority to reorganize their societies in the pursuit of strength. This reorganization alsobenefited from an increase in skilled bureaucrats and commanders, as the militarizing nations needed both talented generals to lead the armies and bureaucracies that were not linked to the continually discontent elites. While these societies were certainly less free due to these changes, the reforms prevented these states from being destroyed and defeated, at least for some time.

This struggle of security against freedom has continued to this day, and the histories of the Qin

and Rome certainly do not provide definitive answers. They must be judged based off what

they achieved and how they achieved it. From there, it must be determined whether the benefits

that these states received were worth what was sacrificed in their pursuit of greater power.

Note

- Hui Fang, Gary M. Feinman, and Linda M. Nicholas, “Imperial Expansion, Public Investment, and the Long Path of History: China’s Initial Political Unification and Its Aftermath,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, no. 30 (2015): 9925.

- Wu Qi. Wuzi (Library of Chinese Classics: Military Science Press, 2005).

- Unknown, Thirty-Six Stratagems, ed. Stefan H. Verstappen (San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals, 1999).

- Alan Bowman, Averil Cameron, and Peter Garnsey, “The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 103-337,” in The Cambridge Ancient History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 28.

- Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1845),572.

- Bowman, et al., “The Crisis of Empire,” 115.

- Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 130.

- Qian, Records of the Grand Historian, 128.

- Fang, et al., “Imperial Expansion, Public Investment, and the Long Path of History,” 9926.

- Shang Yang, “Agriculture and Warfare (農戰),” in The Book of Lord Shang: Apologetics of State Power in Early China (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 134.

- Bowman, et al., “The Crisis of Empire,” 59.

- Qian, Records of the Grand Historian, 44.

- Jia Yi, “Transgressions of Qin,” in The Basic Annals of the First Emperor of Qin, ed. Sima Qian (New York:Columbia University Press, 1993), 81.

- Gibbon, Decline and Fall, 609-612.

- Gibbon, Decline and Fall, 613.

- Qian, Records of the Grand Historian, 58-59.

- Glanville Downey, “Aurelian’s Victory over Zenobia at Immae, A.D. 272,” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 81 (1950): 57

Autore: Vikrum Singh

Fonte: The History Journal of Boston College

Categorie

Tags

Lascia un commento