The English word ‘mercenary’ is derived from the Latin mercenarius, a hireling or someone who is paid for work. The original etymology of the mercenarius is rooted in two other Latin words: mercari, to trade or exchange, and merx, commodity or merchandise. That wider meaning was frequently associated in general usage with faithlessness and greed or desire, as when the Earl of Essex, writing to Elizabeth I, professed that ‘the two ends of my life have been, the one to please you, the other to serve you’, positioning these aspirations against ‘mercenary or self-loving respect’.[1] The pejorative dimension of ‘mercenary’ made the word a recurrent rhetorical weapon to attack the loyalty, legitimacy or credibility of political rivals or religious groups. [2] The civil lawyer Walter Haddon attacked the ‘mercenary ear confession’ of the Counter-Reformation Portuguese humanist Jerónimo Osório’s letter to Elizabeth I.[3].

The Puritan Henry Barrow, in his A brief discoverie of the false church (1591), accused the Church of England of being formed by ‘hireling Lecturers, vagrant & mercenary Preachers’ who, for preserving ‘Romish brawling bawdy court, with all their popish canons, customs’, were nothing more than ‘mercenary Romish Doctors, pleaders, proctors &c. which are to couller & plead the most vile hateful causes which a Christian’s ear abhorred to hear of, or by such wicked blasphemous customs, othes, purgations &c’.[4] Similarly, the idea of writing for hire – the ‘mercenary pen’, ‘[t]hese mercinary pen-men of the Stage’ – reduced the dignity of authorship to a base desire to benefit from the marketplace of print.[5] It is an association that would later surface repeatedly during the English Civil War, due to the increased use of printed polemic to bolster both royalist and parliamentary causes. The equating of ‘mercenary’ with trade or exchange, as well as self-serving covetousness, was not always gender specific. ‘A whore that is mercenary’, wrote Thomas Gainsford,‘will hardly be drawn from her filthy life, she is so fast linked to the love of money’.[6] And a ‘[m]ercenary Woman’, warned the satirical writer Ned Ward in Female policy detected (1695), would ‘submit to your Pleasure’ for ‘a splendid Maintenance’ of silk and satin, only to build ‘a Provision for her self out of the Ruins of your Fortune’.[7]

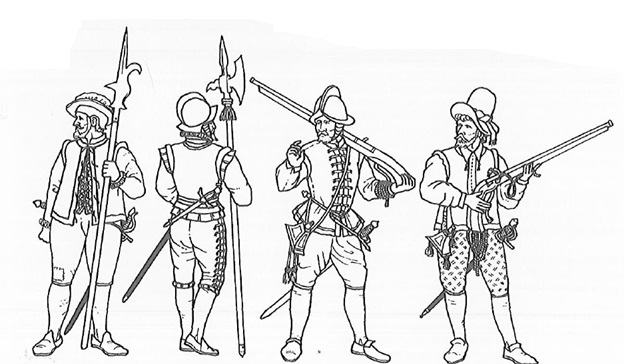

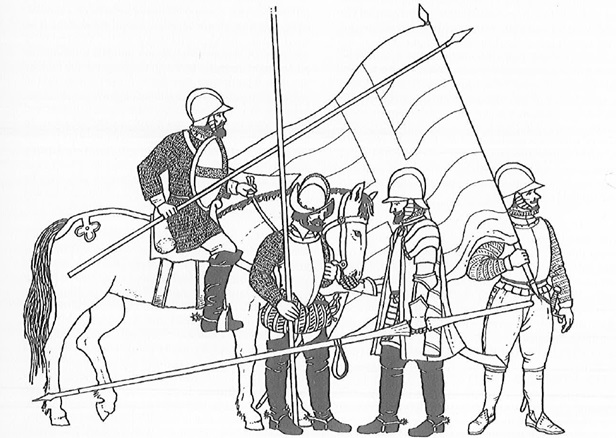

The association between mercenary activity and military service, how-ever, indicated a particularly dominant usage of the word. As professional soldiers who fought for pay rather than their prince, mercenaries became increasingly perceived as the antithesis of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century archetype of the military profession. Walter Ralegh, who served under the French Huguenot leader, Gaspar de Coligny, presented mercenaries as men who were not motivated ‘by any love to the State, but to mere desire of gain, that made them fight’, selling their soldiering skills to the best offer.[8] The services provided by mercenaries were thus less motivated by a political allegiance to a ruler or state than by an economic transaction. Mercenaries tended to show little interest in the cause for which they fought, being primarily motivated by their own private benefit. This element of free agency allowed mercenaries to choose their employers, and even change sides, contributing to their widespread negative image.[9]

In the confessional, dynastic upheavals that accompanied the Reformation and its aftermath, many English military men became itinerant soldiers in the service of the Protestant cause in France or the Low Countries. Professional or voluntary soldiers sought to distance themselves from the negative connotations associated with ‘mercenary’. Soldiers in service to a foreign power could not only justify their actions but also enhance their prestige if that service was related to the alliances and aims established by their natural prince. In 1593, Thomas Churchyard praised those who, like him, were ‘[s] oldiers, whose venter and valiance hath been great, service and labor not little, and daily defended with the hazard of their lives, the liberty of the Country’, complaining that ‘it may be thought that every mercenary man, and common hireling (taken up for a while, or serving a small season) is a soldier fit to be registered, or honored among the renowned sort of warlike people’.[10]0 Another English veteran of the Low Countries, Thomas Digges, presented himself as a part of a group of soldiers who were ‘not mercenarie[s] for pay of strangers’ but who fought abroad under a foreign flag at the service of ‘our natural Prince and Country, (to whom we owe our bodies and lives)’.[11] The English who served with Dutch and French Huguenot troops against Spain and the Catholic League were rarely perceived as mercenaries, but rather as military men who served the realm by protecting the integrity of Protestantism both at home and abroad.

The experience of gentlemen serving the Crown in religious wars abroad contributed to the perception that a staunch adherence to Protestantism was an essential element of English identity and national allegiance. In The defense of the militaire profession (1579), Geffrey Gates considered the ‘exercise of Arms’ in defence of England and Protestantism as an essential duty for ‘every citizen & rural man, gentle or ungentle, noble or unnoble [sic], rich or poor, that meant to prove himself a good Christian, a faithful Englishman, zealous toward the state public of his country, of commendable integrity toward his prince and fervent in the love and maintenance of God’s kingdom and glory upon earth’.[12] In 1626, for example, the clergyman Thomas Barnes praised those faithful English Protestants who went abroad to fight against Catholic powers, appealing to the ‘meaner and vulgar sort’ to join these wars in a call to arms. [13]

English Catholics also developed a similar rhetorical strategy which associated Catholicism with an English identity upheld by those who went abroad to fight for country and religion. A good example is the justification made by Cardinal William Allen to the actions of Sir William Stanley, a Catholic officer sent by Elizabeth I to Flanders. In 1587, Stanley surrendered his garrison to the Spanish army and entered the service of Philip II of Spain. What seemed to be an act of treason, was praised by Allen as a demonstration of ‘Christian knighthood, & an act much renowned’ of a true Englishman who decided to defend the ‘honor, conscience, and Religion, of our country’ against Elizabeth I, a ‘usurper, & Heretical Queen’. [14] This was not the case of a Catholic traitor and mercenary, but of someone who consciously acted to protect the quintessential Catholic traits of English identity from the damages inflicted by an illegitimate monarch who had undermined the true faith at home and abroad.

The crusading spirit that justified war against Catholics also made ac-ceptable the involvement of Protestant Englishmen in campaigns against ‘pagan’ or ‘heathen’ nations in Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, even when these campaigns occasionally involved alliances with Catholics. Thomas Churchyard praised English private soldiers who served in Spanish armies against the ‘Great Turk’ for impeding the expansion of the Ottoman Empire and the spread of Islam. Among these was John Smythe who was ‘so honorable that he advanced the fame of his country by the nobleness of his mind’.[15] Despite being accused of treason for his Catholicism and allegiance to Rome and Philip II of Spain, the life of Thomas Stukeley, who fought under the Spanish flag in Lepanto and died serving Sebastian I of Portugal at the Battle of Alcazar, was celebrated as an example of English commitment in the defence of Christendom against Islamic expansion in George Peele’s play The battell of Alcazar (1594), and popular ballads and poems such as The famous historye of the life and death of Captaine Thomas Stukeley (1605). [16]

If English private soldiers fighting against Islamic powers in the Tudor and early Stuart eras evoked an honourable crusading and chivalric spirit which made it acceptable to serve a Catholic prince in the defence of Christendom, fighting for non-Christian rulers was more difficult to justify. Englishmen who served the Ottoman sultan or the Mughal emperor were presented as mercenaries or renegades. In South Asia, the East India Company was frequently troubled by desertions of military men who opted to join local potentates or serve the Dutch East India Company or the Portuguese Estado da Índia. Although his brother Anthony served the ruler of Morocco in 1606, Sir Thomas Sherley, for example, complained that Europeans and Englishmen who served the Great Turk were ‘for the most part rogues, & the scum of people, which being villains and atheists, unable to Hue [sic] in Christendom, are fled to the Turk for succor & relief’. [17]

Whether employed to fight for Protestant armies in Ireland or Catholic armies in the Ottoman Empire, mercenaries tended to be portrayed as marginal and roving individuals who did not belong to the established social order for a range of economic, political, or religious reasons. This perception was often motivated by the frequent recourse to the forced conscription of convicted criminals, vagrants, and unemployed men in Tudor and Stuart armies, especially in the expeditionary forces sent to Ireland. The background of these recruits led Thomas Churchyard to criticise the ‘mercenary multitude of troops’ led by the Earl of Essex in Ireland. [18] ‘Mercenary’ was thus a word that could be applied not only to a group of professional hired soldiers, but also to disliked volunteer soldiers whose behaviour or social origins clashed with the aristocratic martial ethos.

Mercenary armies had long been comprised of diverse nationalities. During the English civil wars, the employment of foreign soldiers became a particular issue of contention. The high number of desertion and defections among foreign soldiers serving both royalists and parliamentarians contributed to a widespread distrust on the reliability of ‘outlanders’. Foreign soldiers of fortune, such as the Croatian Carlo Fantom, became notorious for treacherous behaviour. Described by the antiquarian John Aubrey as ‘very quarrelsome and a great Ravisher’, Fantom initially served the parliamentary forces and then changed sides for the royalist camp. [19].

According to Aubrey, Fantom assumed his mercenary condition, having declared: ‘I care not for your Cause: I come to fight for your half-crown, and your handsome women: my father was a R[oman] Catholic; and so was my grandfather. I have fought for the Christians against the Turks; and for the Turks against the Christians’.[20] Aubrey’s short biographical notes on Fantom present this peripatetic Croatian who ‘spoke 13 languages’ as a true personification of the villainy associated with the mercenary.[21] Aubrey’s account of Fantom offered an extreme example of the untrustworthiness of foreign mercenaries. The soldier’s pillaging, Catholic sympathies, and performing past services for the Ottoman Empire embodied the dangers of employing foreign soldiers. The violence and devastating impact of the English civil wars, and the significant presence of foreign soldiers fighting for both sides, reinforced rising xenophobic feelings, especially among Parliament’s staunch Protestants. Rumours that Charles I planned to recruit foreign mercenaries from across Europe allowed parliamentarian propaganda to present the New Model Army as a truly English army, void of foreign corruption. [22]

If an English mercenary abroad was a potential traitor, a foreign mercenary in England threatened domestic harmony. The dangers posed by mercenaries constituted thus a threat to national identity. As Daniel Vitkus rightly noted, these were ‘rogue cosmopolitans’, highly mobile individuals who easily crossed physical, political, and religious borders. [23].

This border-crossing ability contributed to a perception of mercenaries as outsiders who did not belong to the established social order due to a range of socio-economic, political, and religious reasons. Their unstable identities and willingness to simply follow their self-interest questioned not only the parameters which defined the still tenuous conceptions of national identity, but also the authority of the state and its capacity to control the movements and behaviour of its populations. Indeed, the accusations or praise of mercenaries echoed the growing tensions between an idealised English identity and the more nuanced realities imposed by a geopolitical scenario shaped by the post-Reformation and overseas expansion.

Note:

1 The Earl of Essex to the Queen, 1595 [?], Hatfield House, CP 58/20r.

2Sarah Percy, Mercenaries: The History of a Norm in International Relations (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 51.

3 Walter Haddon, Against Jerome Osorius Byshopp of Silvane in Portingall and against his slaunderous invectives (London, 1581; STC 12594), p. 50.

4 Harry Barrow, A brief discoverie of the false church (London [?], 1591; STC 1517), pp. 46, 230.

5 A prefatory discourse (London, 1681; Wing A3032), p. 18; George Wither, The great assises holded in Parnassus (London, 1645; Wing W3160), sig. E3r; Richard Brathwaite, An excellent piece of conceipted poesy (London, 1658; Wing B4263); Vincent Alsop, Melius inquirendum (London, 1678; Wing A2914), p. 12.

6 T[homas] G[ainsford], The rich cabinet (London, 1616; STC 11522). p. 166.

7 Edward [Ned] Ward, Female policy detected (London, 1695; Wing W734), sig. F1v.

8 Walter Ralegh, The history of the world (London, 1617; STC 20638), p. 379.

9 Percy, Mercenaries, p. 51; Frank Tallet, ‘Soldiers in Western Europe, c. 1500–1790’, in Fight-ing for a Living: A Comparative History of Military La-bour, 1500–2000, ed. by Erik-Jan Zurcher (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013), pp. 163–164.

10 Thomas Churchyard, Chuchyards challenge (London, 1593; STC 5220), p. 85.

11 Thomas Digges, Foure paradoxes, or politique discourses, ed. by Dudley Digges (London, 1604; STC 6872), p. 69.

12 Geffrey Gates, The defense of the militarie profession (London, 1579; STC 11683), sig. G2r.

13 Thomas Barnes, Vox Belli: or, an Alarum to Warre (London, 1626; STC 1478), p. 40.

14 William Allen, The copie of a letter written by M. Doctor Allen (London, 1587; STC 370), sigs. B3r–v.

15 Thomas Churchyard, A generall rehearsall of warres (London, 1579; STC 5235.2), sig. D4r.

16 George Peel, The battell of Alcazar (London, 1594; STC 19531); The famous historye of the life and death of Captaine Thomas Stukeley (London, 1605; STC 23405).

17 ‘Discours of the Turkes by Sir Thomas Sherley’, in Camden Miscellany, Vol. XVI, ed. by E. Denison Ross (London: Offices of the Society, 1936), p. 4.

18 Thomas Churchyard, ‘The Fortunate Farewell to the most forward and Noble Earl of Essex

[London: 1599]’, in The Progresses and Public Progressions of Queen Elizabeth, Vol. III, ed. by John Nichols (London: J. Nichols and Sons, 1823), p. 433.

19 John Aubrey, Aubrey’s Brief Lives, ed. by Oliver Lawson Dick (London: Secker and Warburg, 1950), p. 105.

20 Ibid., p. 105.

21 Ibid.

22 Matthew Hoppe, Turncoats and Renegadoes: Changing Sides during the English Civil Wars (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 69–72; Mark Stoyle, Soldiers and Strangers: An Ethnic History of the English Civil War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), pp. 102–110, 149, 204.

23 Daniel Vitkus, ‘Rogue Cosmopolitans on the Early Modern Stage: John Ward, Thomas Stukeley, and the Sherley Brothers’, in Travel and Dra-ma in Early Modern England: The Journeying Play, ed. by Claire Jowitt and David McInnis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 128–149

Autore: Das, Nandini, João Vicente Melo, Haig Z. Smith, and Lauren Working. “Mercenary.” In Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England, 174–79

Fonte: JSTOR

Categorie

Tags

Lascia un commento