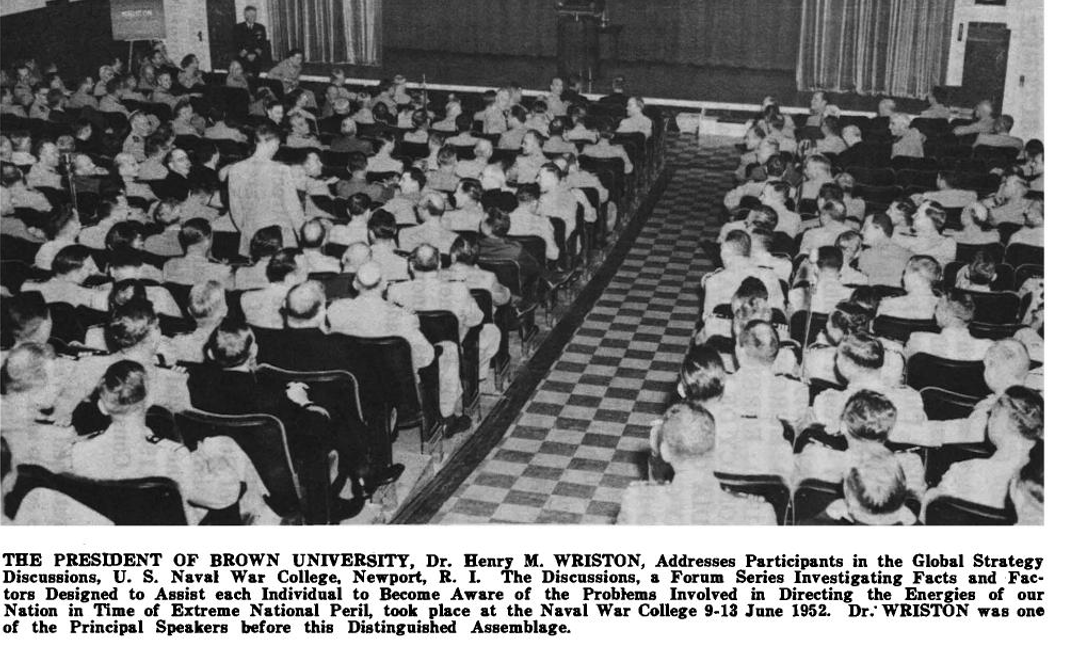

A lecture, previously labelled “restricted”, delivered at the Naval War College

on 11 June 1952, in the Global Strategy Discussions. Basic strategy must be determined by a perpetual remembrance that the world is round. Like most other important observations this may be considered obvious, but its realization in the abstract and its application in the concrete are two different things.

Basic strategy must be determined by a perpetual remembrance that the world is round. Like most other important observations this may be considered obvious, but its realization in the abstract and its application in the concrete are two different things. One has only to observe political behavior over the years to ap-preciate the fact that there is a sharp difference between those two points of view—the abstract and the concrete. Many who say it is round do not act as though it were.

If anything were needed to teach us that lesson, Korea would demonstrate it. Though it was explicitly left outside our defensive perimeter, once aggression started, we made a very heavy commitment after only a few hours of consideration. Despite the absence of a smashing victory and in the presence of a virtual stalemate, no presidential candidate has suggested we should pull out. That is a very persuasive index of public support of the decision, even though the war is far from “popular.”

We are also well aware that the French effort in Indo-China is essential to the containment of aggression. What General Bradley has called “war by satellite” has done much to make clear the idea that ali points are vital, and that security in one region cannot be bought by neglect of another. We must ever bear in mind Stalin’s aphorism to the effect that the road to victory in the West is through Asia. Clearly that does not mean that we should concentrate on countering aggression in Asia alone; it does mean we cannot neglect Asia (Far, Middle, or Near), nor yet Africa. or Latin America, if Europe—and ourselves—are to be saved.

The second basic principle is that change is the rule in international relations. The essential reality of diplomatc history is the fluidity of coalitions; shifts from one side to another are often rapid and decisive. “A sharp observer has commented that one of the charms of power politics is that no one has time to become tired of his friends.”

The history of international relations is full of victorious allies who fell upon each other after the moment of victory. Our own times have manifested this: from the war-time alliance with Russia in the first World War, to our support of the White Russians and the invasion of Russian territory and the cordon sanitaire, through to the admission of Russia into the League of Nations and a period of collaboration, the decision of Russia to ally with Hitler and the reversal by which it allied with the enemies of Hitler, and now becomes our potential enemy. All this should be fresh in our minds; it is less extraordinary than one might suppose.

The behavior of Italy toward the Triple Alliance as the first World War of the 20th century developed provides a further illustration. Its carne to the Paris peace conference as a victor and one of the Big Four, but after disillusionment it turned to Fascism and to a new alliance with Germany. Following its defeat as an enemy in the second World War, it became first a collaborator, now an ally.

The position of Vichy France and of French North Africa after the collapse of May and June 1940 is another example. China before and after the triumph of Mao and the collapse of the Nationalist power on the mainland is stili another. There is the change from the Morgenthau Plan for Germany to the Bonn contractual agreement. We could also list the position of Japan: its relatively long alliance with Britain, one of our associates in the first World War, and then the reversal to become one of our enemies (some think our principal enemy), its surrender on the deck of the Missouri, and now again its restoration under our leadership to the family of nations with a status of semi-alliance. Tito was lately an implacable enemy shooting down our planes. Now he is an active collaborator in some phases, but stili cannot come to an agreement with Italy over Trieste.

These are all illustrations that change is the order of the day. The idea that there will be no more such dramatic shifts is illusory. Consider what would happen if the Communists were to win an election in Italy or if de Gaulle were to take over France or if extreme nationalists were to master Western Germany or if there was another break in the Soviet controlled area by which a satellite left the Russian orbit.

We must not think that the United States is unique and has escaped this changeability. In the effort to stay clear of the wars that dogged Europe after the French Revolution we suc-ceeded in fighting both sides. Our long habit of regarding Britain as the enemy disappeared with the diplomatic revolution at the end of the 19th century. Even so, we were not ready to accept the obvious conclusion and, when World War broke out in 1914, Wilson urged us to be neutral in thought and word as well as deed. In the effort at neutrality, we developed dangerous tensions with Britain, from the consequences of which we were both saved by the colossal errors of the German government.

Stili unwilling to accept the clear inferences to be drawn, we became an “associated power” rather than an ally. After taking the lead in establishing the League of Nations, we eschewed it. In 1939 we again attempted neutrality, and only after a direct assault upon us did we become allies in word as well as deed.

Perhaps it is in remembrance of this record, of which we are often blissfully unconscious, that present allies so often show nervousness as to the stability of our policy. I would not have it thought for a moment that United States policy is in any degree more unstable than that of other nations. It must be clear, how-ever, that we should not look upon others with lofty scorn, neglect-ing to recall our own record of change.

Moreover, it is essential to emphasize the fact that dictatorships are neither more constant in political orientation nor more successful in diplomatic strategy than other forms of government. In order to make the point it is necessary only to think of the marriage of convenience between Hitler and Stalin just before the opening of the second World War of the 20th century; and then of Stalin’s reversal after Hitler’s reversal. We have also the illustration of Tito. One could go on indefinitely showing that the tendency to reverse alliances, the rule of change, is just as applicable to dictatorships as to democracies. We have, therefore, no reason to regard this tendency in international relations as attached to any particular form of government.

These and dozens of other less conspicuous evidence of the essential fluidity of politics under every form of government from democracy through totalitarianism must be constantly borne in mind. Our security can be menaced by a mental fixation which regards the whole of the Communist world as a closely and rigidly controlled Moscow axis. This mistaken concept can keep us from making the constant adjustment which is essential if pesce is to be preserved and is even more essential if we are to have allies should war come.

Obsessive thinking is rigid and leads to false assumptions. In every approach we should maintain the highest degree of flexibility of mind. Such a phrase as the Iron Curtain is useful up to a point, but then it becomes something of a shutter over our own eyes. If you hold a penny dose enough to your eye, it will blot out the world a copper curtain. Back of the so-called Iron Curtain are fault lines; there are tensions and strains within the Soviet hegemony which can be exploited and should be exploited.

It is said that wthin Russia itself there are 20 million prisoners in forced labor camps. That is to say, according to John Foster Dulles, there are at least twice as many prisoners at forced labor as there are members of the Communist party within the Soviet. There could be no clearer evidence of tension and strain.

Incorporated wthin the U. S. S. R.are many peoples Lithuanians, Estonians, Latvians, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, and many others. Despite intense efforts at consolidation there remain cultural, religious, and political traditions which are greatly prized. Police action can to some extent suppress their manifestation, but it cannot destroy folk memory or hope. So long as tradition and hope survive there is potential instability.

Moreover, there is constant resort to purges in satellite countries: in Bulgaria, in Czechoslovakia, and most recently in Romania with the purge of Ana Pauker. That last episode was typi-cal of what has happened in one satellite after another. Even dis-counting the validity of the charges made in any specific case, it is perfectly clear that the forces of nationalism wthin the sat-ellites are extremely powerful. Though their manifestations may be suppressed by purges and by the dominane of the secret police, beneath the surface there runs a very deep and powerful current.

Furthermore, in every dictatorship the struggle for power is perpetual, as well as intense. Since it cannot be waged upon the urbane level of bitter word and bland ballots, it must be carried forward by the desperate methods of political assassination, even though that action sometimes follows legal forms., None of this discounts the fact of Russian hegemony, but we make a mistake when we help consolidate that hegemony by assuming it to be more complete, more successful, and more stable than it really is. To fail to widen the rifts by neglecting to take advantage of tensions is a major error of judgement.

It should be clear that the right attitude of mind towards its problems is an important foundation for American strategy. This involves among other things, and fundamentally, the avoidance of a mind set which establishes a specific power group as the solid, and perpetual, enemy. Overconcentration upon one situation dis-torts perspective on others and destroys flexibility in dealing with the principal problem.

The dangers of mental fixation are becoming rather pain-fully clear in our relationship with our allies. Queen Juliana on her recent visit spoke with a voice of calm sanity when she said that the world cannot be dominated by nervous wrecks. She said with a good deal of bluntness, which was made more palatable by her personality, that the United States in its overconcentration upon the Russian menace was pressing Europe too hard and forcing the pace to such a degree that our allies are often irritated. The clear inference that we were building up emotional resistance which we would be well advised to soften by more alert sensitiveness to the views of other nations.

Queen Juliana was only the latest, and perhaps the most tactful, person to cali these things to our attention. You will remember that a little over a year ago Canada’s Minister for External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson, expressed the irritation of our nearest neighbor and our most constant international companion when he said: “The days of relatively easy and automatic political relations with our neighbor are, I think, over.” “We are not willing to be merely an echo”.

The only time the American people seem to be aware of our existence is when we do something they do not like.” And he went on to say that Canada has “more outstanding problems with the United States this year than in any year of our history.” As evidence that this was not a passing show of irritation, we have the recent officiai protest against the use of a detachment of Canadian troops at Koje, separated from the Canadian command. This should be a reminder of our own attitude at an earlier time when the French tried to incorporate some of General Pershing’s troops into the generai command without giving our commanding officer adeguate control.

Earlier this year the Foreign Minister of Brazil made a complaint similar to that of our northern neighbor. He asserted that the United States could no longer take the support of the Brazilian people for granted and urged that Brazil be treated as an equal if her assistance was really desired. The irritability of Britain and France are too well known to require extended comment.

None of these instances leads to the conclusion that we need lose momentum merely by being considerate of the views and feel-ings of other nations. On the contrary, more alert regard for the sensitivities of our allies and friends may well strengthen our posi-tion vis-à-vis our potential enemy.

It would be disastrous if the view that we are pursuing a national vendetta against Russia were to gain ground. The existence of that suspicion is indubitable; it should be allayed. In this connection it is well to remember one sacrifice we are pressing on our Western European allies which we are unwilling to share. Only in Europe are negotiations proceeding that restrict sovereign rights over vital economie resources and over military forces. That is a severe emotional wrench which must be treated with patience and sympathy, whereas some roving congressmen have shown neither. We must not ask sacrifices of other nations which would prevent their governments from remaining in office.

Tact, however, need not reduce energy in the pursuit of agreed programs. Because international relations exhibit constant change, we must pursue policies which are dynamic. Mere hesitation or stopping will not prevent change; even if we were to remain static, others would continue to move. Since change will be forced upon us, it is better to retain the initiative.

We have to base our plans for Europe on a series of assumptions but remember that all are subject to alteration. One assump-tion is that the contract of settlement with Germany will be approved by the several parliaments and will go into full effect. Another is that the European army will be realized that Germany will sup-ply its share of the troops who will remain subject to the unified command. These hazardous assumptions must be made in the hope and for the purpose of creating such a formidable barrier that Russia will not precipitate a war.

We also must take into account that war by satellite might precipitate a German civil war of far greater magnitude than the Korean war. Otto Grotewahl, the premier of East Germany, has plainly hinted that, if the contract of settlement is signed and goes into effect, Germany will become another Korea. He has spoken openly of civil war and there are many evidence that the rearming of the East has been stepped up since it became clear that Russia’s offer of union neutrality, and the right to have its own armies was not going to prevent the signature of the contract.

Another possibility is that Schumacher and his associates may defeat the contract in Germany or that it may be defeated in the parliaments of some of the other nations involved. Under such circumstances the army would never be organized upon the contemplated basis. That would leave us with an expenditure of vast sums of money and very great commitments without the gains in security which our present plans contemplate.

On the other side of the world, we have to rely upon Japan in the light of our commitments under the San Francisca treaty. But if bad faith develops or nationalism sweeps the country or economie pressure leads to a reapproachment with Red China, we must be prepared for those eventualities.

One other observation is required to conclude this section nf the argument. The changes I have been discussing are often functions of a dynamic balance. Sometimes they are essential to the maintenance of such a balance. Sometimes they are only thought to be and are the result of miscalculation of the forces involved. Sometimes an imperialist urge sets change in motion to destroy the balance that is our present estimate of the Russian design. In so far as change is an effort to restare balance it does not involve new national objectives, but only new means of at-taining them.

The third absolutely fundamental factor influencing our strategy is seldom, if ever, referred to: it is ideological consistency. It has become fashionable to say that democracy has no ideology, that the contrast between democracy and communism in this re-spect is absolute. Nothing could be further from the truth. In the formai sense of not having a party line, deviation from which is tantamount to political suicide, there is some color of truth in the remark. Substantively, however, democracy has an ideology as explicit and dominant as anything in the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist dialectic.

The Declaraton of Independence asserted that “all men are created equal.” That is not a vague phrase, although it is easy to mock it and make it seem absurd by pointing out that men are not equal in stature, equal in strength, equal in abilities. What is meant is made clear by the next phrase: namely, “that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and pursuit of Happiness.”

The word “Life” is important. We are so accustomed to taking man’s right to life for granted that it is hard to realize in how many places in the world the right to life is not regarded seriously. We are willing to take a man’s life only when he is a menace to the lives of others. Many states do not permit capita! punishment even under those circumstances. Communists take a man’s life for deviationism, which can mean anything and the evidence for which can be manufactured. In Maoist China man’s right to life is not recognized. Mass executions are staged for the apparent purpose of terrorizing people into subjection. Justice has no relevancy to the proceedings.

The second word “Liberty” is in one sense an even more vital concept. It represents an antithesis of Soviet ideology so fundamental that it is the nearest justification to be found for the division of the world into two spheres. “Liberty” means explicitly that each man may establish his own standards of value, bis own strategy of living; he can set his own pattern so long as it does not impair the rights of others to establish theirs. It guarantees fluidity in society; a man’s ‘position is determined by his own effort, his own capacity, his own personality, and by nothing else whatever. In the communist ideology none of those things is acceptable; its society does indeed attain a sort of fluidity, for neither Stalin nor any of his politburo associates carie to power by reason of birth or rank or privilege. It is, however, fluidity only within rigidly designed channels established by the party; it is not the fluidity that comes from the self-directed self-choices of free men.

The American ideal represents so sharp a contrast with what had previously existed that an acute observer well remarked that the Declaration of Independence “blew Europe off its moral base.” If the document was correct in calling liberty a god-given endowment, it cannot be limited, in its validity, to Americans. Lincoln, as usual, summed up the fundamental idea when he asserted that the Declaration involved “liberty” not alone to the people of this country, but hope to all the world, for all future time.”

That ideology shaped our history. It is that which made this a land of opportunity for the oppressed for more than a cen-tury. It is that which made the United States a revolutionary force and the opponent of tyranny. Under its impulse we were consistently the first to recognize revolutionary governments. Every opportunity was exploited to encourage liberai and national-ist revolutionaries. American agents were active in promoting revolution in South America; others eagerly watched the revolutions of 1848 in Europe; indeed, one went so far as to draft a constitution for a confederation of German states.

When the Austrian charge d’affaires protested secret in-structions for a mission to revolutionary Hungary, Daniel Webster replied: “Certainly, the United States may be pardoned, even by those who profess adherence to the principles of absolute govern-ment, if they entertain an ardent affection for those popular forms of political organization which have so rapidly advanced their own prosperity and happiness, and enabled them … to bring their country … to the notice and respectful regard, not to say ad-miration, of the civilized world.” It was that same spirit which made Woodrow Wilson become the Nero of Europe at the dose of the first world war of this century. It was that which led to his declaration, “The world must be made safe for democracy.”

Wendell Wilkie spoke of this tradition as having provided a vast “reservoir of good will.” It was to this tradition also that General Eisenhower referred when, in the course of his farewell visits to the NATO nations, he described our spiritual strength as vital, together with our economie and military resources. In London, on May 16, he said: “We are going to preserve peace only if we give great attention to three factors. The first and most im-portant is the spiritual strength of our people. How much do we prize peace and freedom and security? How much are we pre-pared to pay for it in terms of individual sacrifices?”

I have lingered on this theme because it is absolutely fundamental. It is necessary to point out that we cannot impose freedom on people who do not value it. We tried it in parts of Latin America specifically Cuba. It is an exportable commod-ity only to places where there is an active market, either natural or stimulated, for it. We are committed by our history to the promotion of human liberty in every piace where it is ardently desired; whenever our policy seems to waver from that orientation, difficulties become acute.

Today, in developing our strategy, we are faced with some exeeedingly hard choices. Historically we have been opposed to im-perialism, even though we have occasionally been infected with it for brief times in our own history, as when we took the Philippines, or when we set out to make the Caribbean an American lake and put our marines in several of the Central American and Caribbean republics.

Now with strategie bases in North Africa we suddenly find ourselves involved in tension between France and that area. We have been faced with the awkward choice between fidelity to an ancient principle and the necessity of maintaining vital allies. In Egypt we are confronted with a dilemma of our fundamental prin-ciples in tension with a strategically vital link. In the Near East our passionate attachment to the Jewish homeland on ideological grounds has led to tension with the Arab world. In the Middle East the flow of oil and the flow of politics run in contrary di-rections.

In dealing with India, we fail to see the similarities between the Indian position today and that which we took during the Na-poleonic wars when Napoleon stood in the position of Stalin and Britain in a position analogous to ours and we wished to pursue a policy of neutrality.

In Korea our ideology is the stumbling block to a truce. We have only to say that our non-communist captives have no right to life or to liberty and turn them over to their communist masters who drove them into battle; by that denial of their right to life and liberty we can probably have an armistice and release ourselves from vast pressures. To yield the point would plague us forever after; whenever men sought to flee tyranny and oppression, they would fear lest we send them back to concentration camps, slave labor, or death.

In a world where force plays so great a part, it is hard indeed to maintain anything like ideological consistency. But if we waiver, we will lose our moral position. That would be disastrous abroad, draining the last drop from that “reservoir of good will” which leads nations to trust our word and to accept it in good faith. Even worse it would disintegrate our domestic front. Those who are old enough to rernember the storm which was let loose by our tempta-tions toward imperialism at the turn of the century do not want to have such another debate precipitated in the. midcentury. Beside it the so-called “Great Debate” of a year or two ago, which is already fading from memory, would be as nothing.

This ideological commitment is so profound that it transcends parties. That is why it is a mistake to speak of a bipartisan foreign policy. We must have a non-partisan or, more accurately, an unpartisan foreign policy. Tactical moves on the diplomatic chessboard are a matter of party management and rightly a matter of party debate; but the strategic concepts to which we are deeply com-mitted rest upon the basic ideology of the United States. They run so deeply through the course of our history, through the fabric of our thought, that they are beneath, above, and around parties.

Only by holding the firm ground upon which our feet have been planted—namely that all men, without distinction of rate, creed, color, are created equal, that all men by the fact of their manhood are entitled to life and liberty only by ideological con-sistency in the pursuit of those aims which distinguish us so sharply from the communists, can we hope to preserve a public opinion within the United States which will make possible the maintenance of adeguate armed forces. Only so can we count upon the con-fidence of allies in our integrity and fixity of purpose.

The fourth basic element in our strategy is a clear perception about such phrases as “total war” and “total peace.” There never yet was a time of total war and there never was a time of total peace. The idea that either of those conditions ever existed is un-real and vitiates our capacity to form sound judgements on the great problems that are before us.

In the long view, for the basic factors that shape our strat-egy there is no sharp difference between peace and war. That distinction is one rather of law and of tactics. The legal distinction is great within the limited area of its significante, but war as such does not directly affect the basic national aims which it is the business of strategy to achieve. The strategical objective remains rela-tively constant; the change from peace to war is a change in em-phasis upon the instrumentalities employed. As war approaches, force moves from a background threat to the post of action. But force is never an end in itself; therefore, tactics should never dominate strategy lest it result in surrender of long-run objectives to short-run advantages.

If we are to take a long view, we must blunt the edge of two sharp words war and peace. If we continue to deal with those two concepts as mutually exclusive, we confuse both the defense effort and the attempt to achieve peaceful objectives. We can gain some quick realization of the fundamental problem by pointing out that determining the start of war is like inquiring when a fire began. There were first of all the materials and conditions to produce fire, there were smoke and smoldering, then a flicker of flame. When in that train of events did fire actually begin? It is so with war, and history is full of arguments about its real onset.

We are faced with a kind of political theory of relativity: absolutes are manifestations of error; only relatives are trustworthy. To express this in the simplest terms possible, let us say peace is the pursuit of strategic objectives by the most economical employment of all the means at our disposal; war is the prosecution of those same objectives by an extravagance of method. That is the essential fact. The basic purposes of war and of peace are the same the promotion of the national interest; the means are also the same in war and peace. The difference is in the intensity with which the various means are employed.

Since economy and extravagance are not absolute but only relative terms, the distinction between peace and war is never absolute, except in a narrowly legai sense. We recently had an illustration of this fact. In arguing the government case for the seizure of the steel industry before the Supreme Court, the Solicitor General spoke of “war” in Korea, and Justice Jackson asked if the Presidnt had not explicitedly denied that it was “war.” In the narrowly legal sense, fighting, even costly fighting, long continued, does not constitute “war.” In a broader context, it is clear that war and peace are relative, not mutually exclusive, terms. The transition from peace to war, therefore, lies in the transfer of emphasis from the economical instrument of reason to the extravagant means of economie pressure and of force. The ends remain reasonably constant.

Autore: Henry M. Wriston

Fonte: Naval War College Review, September 1952, Vol. 5, No. 1 (September 1952), pp. 31-60

Categorie

Tags

Lascia un commento