The domestication of the horse and the invention of eque_rian technology is a momentous event in human history as this aected the nature of transportation, communications and by implication the diusion of languages and culture. Equestrian technology also a`ected the course of military history as this inaugurated the foundations of cavalry warfare. The horse had been transformed from a wide-ranging wild beast into a formidable weapon of war. The basis of this technology was in taking advantage of a gap situated between the horse’s grinding teeth (at the jaw) and the incisors at the front of the mouth. The horse-bit was invented specifically for this purpose: it was placed precisely in that gap (between the incisors andgrinding teeth) in order to dome_icate and control the horse. Archeological studies indicate that the invention of eque_rian technology originated in the ancient Ukraine in circa 4000 BCE, displacing the earlier hypothesis of a Central Asian origin for this technology in approximately 1500 BCE (Gat 2008, 184). Seminal to these discoveries was the archaeological !nd of a 6000-year old horse-tooth from Ukraine’s Dereivka region which shows clear evidence of having been bit- ted as it displays chamfering, fractures and breaking.

The bit on the modern-day horse typically rest upon its mouth’s soft tissue, but the horse tends to slide the bit to its teeth in order to relieve the pressure felt upon the soft tissue. It remains unclear however as to how the wild horse would have been captured to be then be !tted with the (bone or metallic) bit and straps for training. Nevertheless evidence of horseback riding in the Near/Middle East can be traced to the late 3rd to early 2nd Millennium BCE as evident in images (of horseback riding) in the Seal of Abbakalla of Ur, during the reign of Shu-Sin (c. 2037- 2029 BCE), the king of Sumer and Akkad. These show one of the earlie known images from the Near/Middle-Eaast of a human rider atop a horse (Trimm 2017, 231). Breaking the horse to the bit bore five major implications for human civilization (Anthony et al. 1991, 94-100).

The first was the enhancement of hunting capabilities against wild game, roviding the tribe with more access to foodstufs. The second was the individual’s ability to travel faster over longer distances. The third was improved transportation capabilities over longer distances, especially when the horse was linked to wagons laden with cargo and people. The fourth was the option of relocation to distant locales should this become a necessity due to droughts, economic deprivations or attacks by hostile neighbours. The fifth implication was in the military domain: the horse provided the warrior greater mobility and striking power again his potential enemies. Nevertheless, warriors were not able to immediately exploit the potential of warfare (from horseback) just as the horse had been domesticated. This is because the skills of mastering both riding (controlling) the horse and simultaneously deploying weaponry (archery, swords, spears, etc.) from horseback had yet to be mastered.

Equide-proppelled vheeled vehicles

The integration of the skills of riding/control of the horse and fighting from horseback would take many more centuries to evolve. In the interregnum the horse was clearly adapted to e`ective purpose by linking this to yet another invention, wheeled vehicles. By the 3rd millennium BCE (3000-2000 BCE) the Sumerians (modern south Iraq/Kuwait) had succeeded in constructing the first known combat wagon. This was essentially constructed of planks fastened together with mortices, with the platform itself mounted onto four wheels (round discs with no swiveling axles or spokes). The Sumerian wagon however was not pulled by the horse, but propelled by another species of Equidae, the onager. The heavy mass and mode_ pace of the wild onagers made the Sumerian wagon a slow vehicle, capable of a maximum speed of just 12-15 kilometers an hour (Lit- tauer and Crouwel 1979, p.33).

Sumerian Stendard of Ur

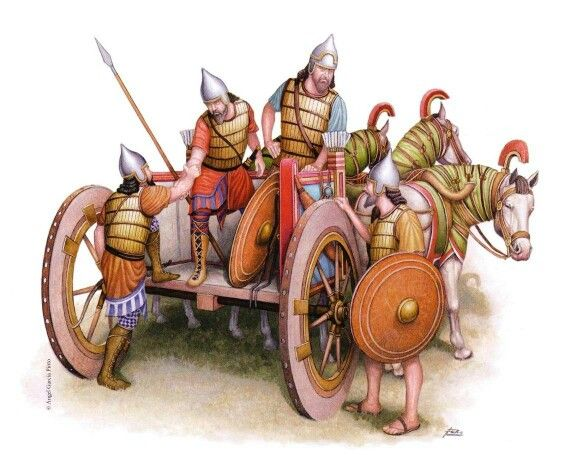

A far more effective military vehicle, the combat chariot appeared sometime in the 2000s BCE (during the latter part of the 3rd millennium BCE). Propelled by the spoked wheel the light weight combat chariot weighed in at a maximum of 25 kg (60 lbs) (Mazzù et al. 2016, 1). Like the Sumerian battle wagon, the chariot had a dedicated driver (for controlling the horse) and a warrior. Unlike the Sumerian war wagon, the origins of the combat chariot are less clear. One trend of scholarship accredits the war chariot’s origins to the ancient Near/Middle East (Littauer and Crouwel 1996, 934–939) with another tracing its origins to Eurasia/the steppes (Di Cosmo 1999, 903) notably the Sintasha-Petrovka region on the Eurasian steppe (bordering Ea_ern Europe and Central Asia).

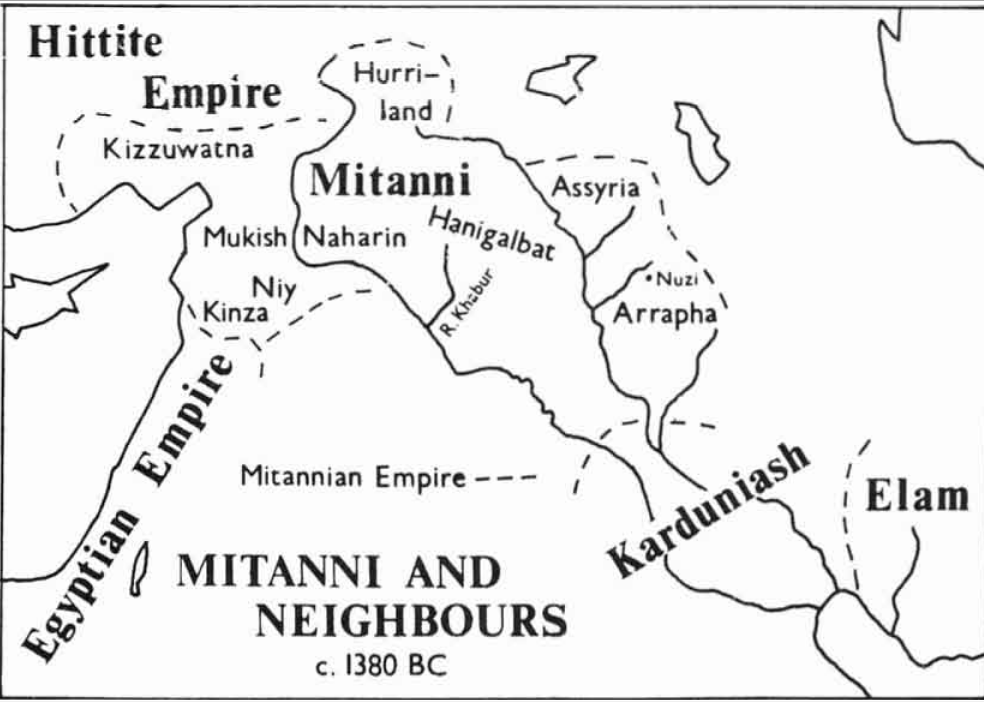

The Eurasia/Steppe origin paradigm is itself divided into two di_inct theories: one suggest that it was the Mittani (arriving from Central Asia) who first introduced this war vehicle into the ancient Near/Middle East (Gat 2008, 326, 344, 377) with another proposing the Hittites (arriving into Anatolia from the Aegean region) as the fist people introducing this technology to the region (Wesfahl 2015, 109). It is just as likely however that the evolution of chariot warfare technology was the result of contacts and mutual in “place between the Steppes/Eurasia and the Near/Middle East that have been in place for millennia (Mallory 1989, 41-42).

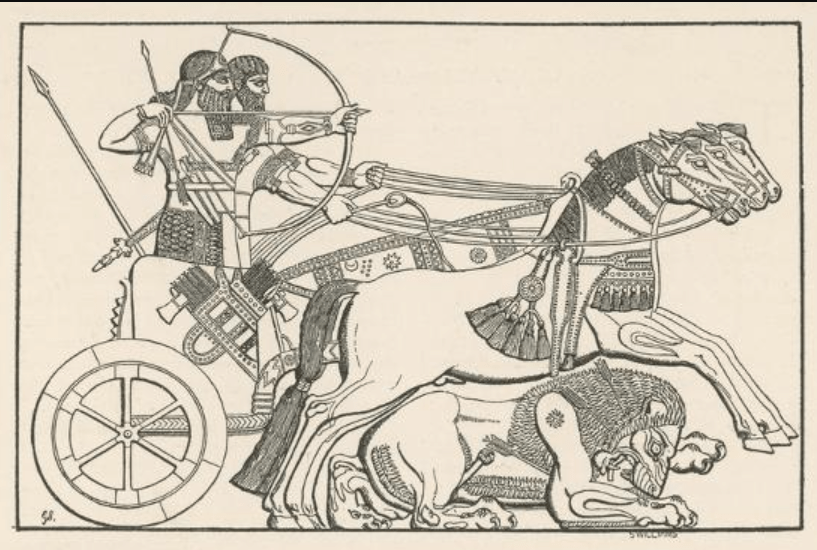

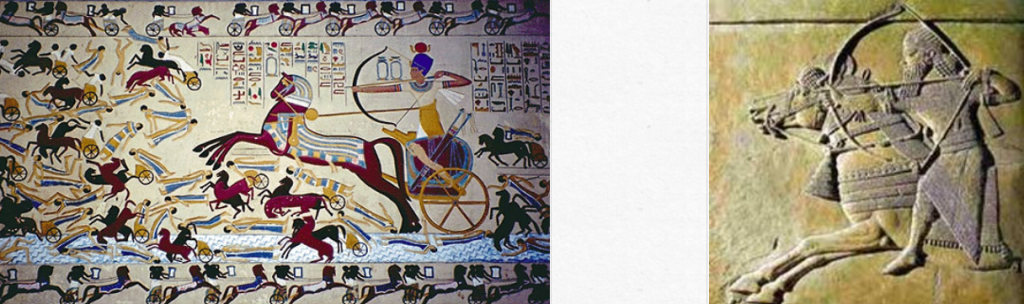

The combat chariot was militarily more effective than the Sumerian wagon in three ways. First was the horse’s superiority in speed in comparison to the onager. The chariot had a maximum speed of 40 km/hour/25 miles/hour versus its Sumeri- an counterpart at (a maximum) of just 12-15 km/hour/7.5-9.3 miles/hour (Otterbe- in 2004, 167). Second, the horse’s speed (and weight) combined with the mass of the chariot (vehicle and passengers[s]) in order to produce significant momentum. Third, the battle chariot’s light-weight design made it significantly more mobile than its Sumerian counterpart. The combat chariot also wielded four advantages again_ enemy infantry: high velocity, mobility, an elevated platform for launch- ing spears or arrows as well as effective reconnaissance capabilities of enemy positions. The chariot now allowed the skills of controlling the horse and deploying weapons to be successfully combined into a single platform. The chariot was to be made obsolete by another upcoming evolution in equestrian warfare untill centuries into the future: a single warrior capable of controlling the horse and deploying his weapons (from horseback). The single warrior on horseback would even-tually render the chariot obsolete.

Accadian combat charriot

The composite bow

A deadly weapon deployed on the chariot platform (and later by warriors on horseback) was the composite bow, essentially constructed of bone, horn and wood, which were laminated together (Benjamin 2018, 30). This was significantly more powerful than the ancient wooden bow, as when the (composite) bow was drawn it was capable of storing far greater (potential energy) than its similar sized (wooden) counterpart. As a result, the released arrow had far greater (kinetic) energy, making it capable of greater penetration over longer distances. The origins of this weapon have often been traced to the Urals and/or Central Asia (Insulan- dar 2002, 49-73). More recent studies sugge that this technology may be traced to the bronze age burial site of Sintasha-Petrovka (dated to 2100-1700 BCE) from which battle chariots as well as a large number of arrowheads have been excavated. The main challenge with this site is that almost all of the bows for these arrows have perished over time, except for one which appears to be the earliest

example of a composite bow as this contained materials such as horn and bone.

What remains unclear is whether these materials were used in the bow’s entire construction (notably the critical bending parts needed to store the necessary potential energy prior to the arrow’s release) (Bersenev et al. 2011, 176, 184, 185). Another possible place of origin for the composite bow may have been the cultural successor of Sintasha-Petrovka known as the Andronovo culture (c. 2000- 900 BCE), (Bersenev et al. 2011, 181) which has been identified as the original homeland of the proto Indo-Iranian language family (Beckwith 2009, 49). By the first millennium BCE the Andronovo region was dominated by Iranian speakers who then migrated into Central Asia and further east across Eurasia and westwards towards the Ukraine region (Mallory and Adams 1997, 20-21). As noted by Pullyblank, it was the invention of the composite bow which led to a profound increase in military activity among these Eurasian nomads in the 1st millennium BCE (1983, 451-452). The spread of composite bow technology into the ancient

Near/Middle East is believed to have first taken place by chariot-borne nomadic warriors who deployed this weapon from their mobile platforms. As a result, this technology may have been introduced into the region by the Mittani (arriving from central Asia onto the Iranian plateau towards the Levant region), Hittites (arriving into Anatolia from the Aegean) and possibly the Hyksos invading the Mediterranean regions. What is clear is that this technology spread into

the ancient Near/Middle East Empires such as Assyria, Egypt, etc. to become a standard archery weapon for both infantry and battle chariots. The evolution of equestrian technology would allow for the individual rider to wield the composite bow, an innovation which would militarily surpass the archery-chariot platform over the ensuing centuries. By the 6th century BCE, the archery of Iranian horsemen was in the range of 60-70 to 160-175 meters, with a maximum not exceeding 350-450 meters (Nefedkin 2006, 6).

Advent of warfare from Hoseback

The dual skills of horse control and weapons bearing from horseback are understood to have appeared by the first millennium BCE within the regional arc encompassing eastern Europe/Ukraine region to Central Asia (Gat 2008, 190, 192). By this time this large swathe of territory would have been primarily dominated by nomadic Iranian speakers who had expanded out of their original homelands in the Andronovo region (Mallory 1989, 61-62) westwards into Ea_ern Europe and southeastwards into Central Asia.

The individual warrior on horseback would have held signi!cant advantages over his more sedentary opponents, notably those in the contemporary Near/Middle East. Like the chariot, warrior horsemen wielded two significant advantages against non-equestrian opponents on the battle!eld. First, the warrior on horseback could rapidly ingress into or egress out of the battlefield. Second, the warrior horse-man was able to hurl spears and discharge arrows from a relatively safe distance – and simply retire if enemy infantry charged towards him. While contemporaryNear/Middle Eastern armies did have sophisticated forces of chariots, the equest

trian warrior essentially combined the functions of both vehicle and driver in one person. While chariot forces were certainly formidable with respect to the speed and shock of their attacks, warriors on horseback posed an even greater challenge to settled communities. This was because the single horseman was more maneu-verable and “fluid on the battle!eld than the chariot which was more limited (than the individual horse) by the geography of the local terrain. These factors enabled the nomadic warrior horsemen to e`ectively raid and attack urbanized centers situated in prosperous territories.

What made the nomadic horsemen especially versatile was the composite bow alluded to previously. This combination (of horseman and composite bow)in the 1st millennium BCE allowed nomadic societies to form powerful military contingents capable of challenging the settled civilizations situated to the south and east of the Eurasian realms. The arriving nomadic composite bow-equipped horsemen (henceforth referred to as horse archers) would now be posing serious military challenges to the sophisticated armies of the ancient Near/Middle East.

Of course, the weapons inventory of the warrior on horseback would not be limited to the composite bow as he could also deploy spears, javelins, etc. as wellas hand-held bladed weapons.

Rapid attacks and raids on horseback were often diacult to quickly defend against, with the antagonisrs often being able to escape retribution by simply riding away after their attacks. Despite these advantages, incoming nomadic Iranian horsemen in 900-800 BCE were themselves to be challenged by the sophisticated armies of the ancient Near/Middle East, no-

tably the Neo-Assyrian army which developed their own military countermeasures against mounted forces.

Clashes of the Neo-Assyrian army aginst the Medes and Persians

Assyria was initially founded in contemporary Iraqi Kurdi_an by king Shamsi-Adad I (r. 1813-1781 BCE). A modest kingdom at first , Assyria was essentially confined to Ashur, Arbil and Nineveh. The Assyrians of the 2nd millennium BCE were contemporaries of the militarily more powerful Egyptian kingdom (Garcia 2010, 5-42) and Hittite Empire (Bryce 2010, 67-86). By the 15th century the Assyrians had become the vassals of the Mittani but regained their independence four centuries later. Nevertheless, the territorial extent of the Assyrian kingdom remained con!ned to its original core by the late 2nd millennium BCE. Assyrian fortunes changed with the enthronement of Adad-Nirari II (r. 911-891 BCE) just as the Egyptians, Hittites and Mittani were in military decline. The Assyrians in particular appear to have been influenced by the military tactics and equipment of the Hittities (c.1600-1200 BCE) (Speidel 2002, 257-258). One example was scale armor (rounded type metal pieces woven onto a fabric or leather base) of the type

utilized by the Hittities as seen at the King’s gate at Hattusa in Anatolia (Burney 2004, 29). This is seen worn by Assyrian charioteers of the 9th to 10th centuries BCE (Healy 1991, 33). The origins of scale armor technology can be traced as far back as the 15th century BCE from a wide swathe of territory spanning from ancient Cyprus and Egypt in the eastern Mediterranean into Syria, northern Mesopotamia, Anatolia and northern Iran (Potts 2012, 154).

Prior to Adad-Nirari’s reign, depictions of Egyptian and Assyrian cavalry in c.1400-1200 BCE show these as pairs of horsemen where one of these engages in archery with the second rider in control of the archer’s eed (Kradin 2016, 1). These types of paired horsemen were essentially acting as a chariot team minus the chariot itself (Gat 2008, 381). Absent from Egyptian and Assyrian armies in the 14th to early 13th century BCE is the warrior horseman capable of inde- pendently controlling his horse and deploying his weapons (such as spears or ar- chery) from horseback. In contra the first groups of nomadic Iranian-speakers arriving into northeast Iran and Afghanistan by approximately the 1100s BCE were capable of independently fighting from horseback. As these fanned out into the Iranian plateau, other Iranian-speakers to be later known as Saka (Scythians), Bactrians, etc. were dominating much of Central Asia by this time (Mallory 1989, 24-65). The nomadic Iranian arrivals into contemporary Iran did result in a number of influences upon local Near/Middle East equestrian technologies,notably with respect to equipment such as the harness for control of the horse (Kradin 2016, 1).

Neo-Assyrian cavalry – Sargon II

The Neo-Assyrian’s military capabilities were to be enhanced significantly, due largely to their willingness to adapt to contemporary military conditions, notably with respect to the tactics and equipment of their enemies. Neo-Assyrian military ingenuity however is not necessarily traced to the time of Adad-Nirari II, as the early Assyrian kingdom had been obliged to contend with militarily more powerful and numerous foes ever since the foundation of the Assyrian kingdom in the preceding millennium (Anderson 2016, 4-5). The Neo-Assyrian army became one of the most eacient military in_itutions during its tenure (Chaliand 2014, 48). At its height the Neo-Assyrian army is estimated to have stood at 100,000 troops (Dezső 2016, 141, 145), with advanced capabilities in siege operations, set-piece battles and raiding operations (Nadali 2010, 117).

King Tukulti-Ninurta II (r. 890-884 BCE) was to organize the ancient world’s first known formal cavalry units within astanding professional army (Anderson 2016, 5). The Assyrian cavalry arm become an independent branch within their army (Dezső 2012, p.13) with their ranks further expanded by re-training a segment of the Assyrian infantry to fight as cavalrymen (Eadie 1967, 161). Nevertheless, these were light cavalry at this time, primarily suited for skirmish and reconnaissance operations. Their main weaponry was the bow however the Assyrian caval

ryman of this time was not of the nomadic horse archer type, capable of both deploying his archery and controlling his horse. For this, another mounted rider was needed to control his horse as he discharged his arrows. The second rider is essentially holding the reins of both horses as the mounted archer fires his weapon. This two-man cavalry system is displayed on the bas-reliefs of the palace of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883-859 BCE) (Healy 1991, 20). Interestingly, the rider controlling both horses is also seen armed with a spear, but neither rider appears to

be armored (Baumer 2012, 85). The Ashurnasirpal II bas-reliefs at Nimrud also depict the Assyrians clashing with nomadic Iranian cavalrymen. Notable in those depictions is a cavalryman in typical Iranian riding dress (loose fitting tunic and trousers, conical cap, high boots) sitting atop a saddle cloth engaged in the Parthian shot: firing his archery backwards as he gallops away from his (Assyrian) enemies (Wise 1987, 38).

Reforms attributed to Ashurnasirpal II’s successor, Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BCE) resulted in the transformation of the Assyrian army from a seasonal (summer only) force conscripted from native Assyrian levies into a professional military capable of campaigning throughout the year under diverse climactic and geographical conditions throughout the empire’s marches (Healy 1991, 18). It is from the time of Shalmaneser III when Assyrian references are made to the Mada/Madaja (Medes) and Parsu/Parsua/Parsuash (Persians) (Gelb et al., 1998, 115, 321). By this time period the Medes had become the dominant Iranian tribe followed by the Persians. Iranian nomadic peoples had by now fully settled in both eastern and western Iran where (notably the latter) were already engaged in clashes against the Assyrian army. The Medes are reported as having been composed of six distinct tribes (Magi, Paretaceni, Busae, Budii, Struchates, and Arizanti), with these settled within a roughly triangular territory situated between Aspadana (modern Isfahan, central Iran), Rhagae (near modern Tehran) and Ecbatana (vicinity of modern Hamedan in northwest Iran) (Diakono` 1985, 75). The major Persian tribes by the time of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) are reported as the Maraphians, Maspians, Pasargadae, Derusiaei, Dropici, Panthialaei, Daï, Sagartians, Germanii and Mardians. The Assyrians placed a top military priority towards the subjugation of these Iranian tribes. This is evident in Assyrian references to twenty-seven kings of the Persians who were obliged to bring their tributes to Shalmaneser III (Mallory 1989, 49). The Assyrians however proved unable to permanently subdue the military potential of the Iranian tribes, as evidenced by the campaigns of later Assyrian kings.

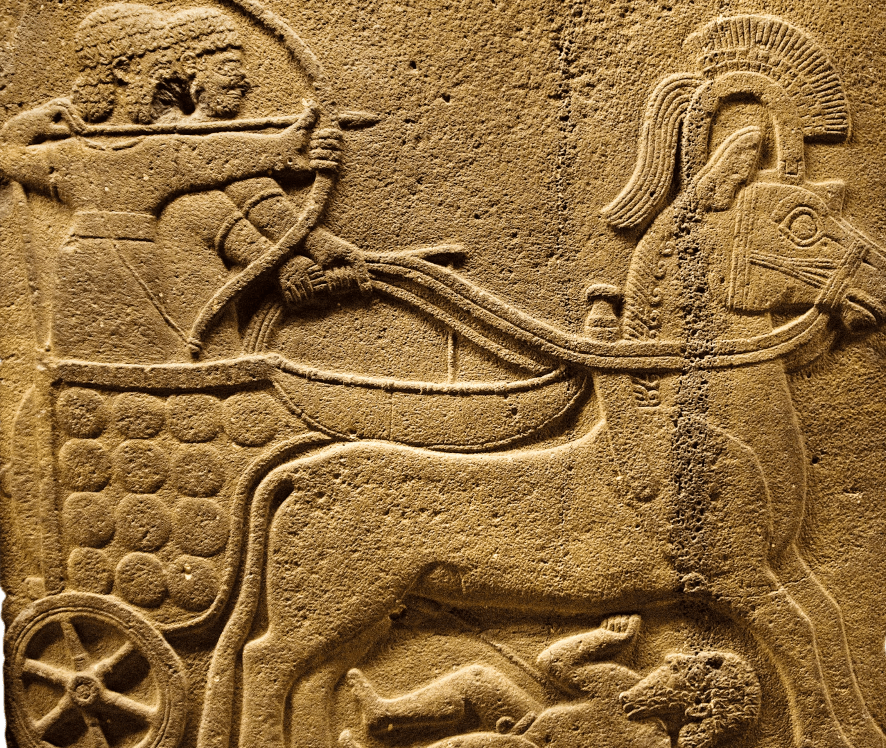

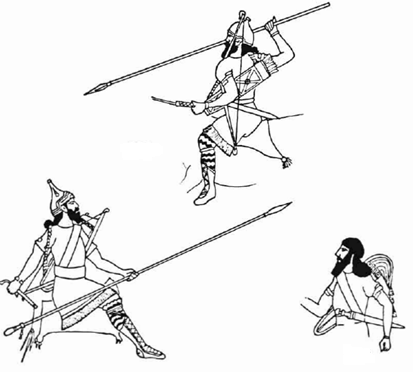

Nomadic Iranian tactics against the Assyrians were often of the rapid attack and retreat type (Nefedkin 2006, 6) much as seen in the aforementioned Nimrud bas-reliefs: attacking with archery on horseback to then apply the Parthian shot tactic as their (Assyrian) opponents engaged in pursuit. These tactics and combat gear were not unique to the Mede-Persians now clashing with the Assyrians but with the larger population of Iranian-speaking nomadic riders now permeating the Eurasian steppes, Central Asia and ancient Ukraine regions. Mede tactics however were not confined to hit and run but also for close quarter combat again Assyrian infantry, cavalry and charioteers. This is evident in the bas-relief of the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud depicting Mede cavalry equipped with swords. Intere_ingly, before their sustained encounters against nomadic cavalry in Iran, the Assyrian military had been primarily an infantry force (Dawson 2001, 190), which along with their chariot forces had been militarily defeated in their initial military encounters again_ the nomadic Iranian cavalry (Dandamaev and Lukonin 1989, 224). This was because chariots were militarily less efficient that nomadic horse warriors. The chariot was often operated by two (driver, archer) or three (driver, archer, shield bearer), making the warrior to horse ratio often 2-1 or 3-1. In practice, chariots were pulled by more horses, however if even one horse became wounded, it would effectively render the entire platform useless. In addition, if the chariot warrior was wounded or killed, the chariot would again become unusable. In contrast the horse warrior to horse ratio was 1-1, without the need for additional crew or the expensive chariot (which was prone to breakdown and required repairs).

Assyrian combat charriot

The nomadic cavalryman also wielded a significant mobility and maneuverability advantage over the chariot in the multi-varied and diacult terrain of Iran which varies with re-

spect to waterways, muddy earth, mountainous and hilly territories and forests (in northern Iran). The chariot was of little or no military utility in these types of geography, expect in southwest Iran (modern Elam and Khuzestan regions) where the terrain is mainly flat and desert like, ideal for wheeled combat platforms. But even in such terrain the nomadic cavalryman wielded a significant advantage over the chariot with respect to maneuverability and agility.

The Assyrian cavalry’s rise in military pro!ciency has been attributed to its battle experiences against the highly eacient nomadic cavalry of the Medes and Persians (Anderson 2016, 6). This is evident in a transitional phase, where four changes can be seen with respect to Assyrian cavalry in the palace bas-reliefs of Ashurnasirpal II. First, there appears to be less reliance on chariots and second, there are images of Assyrian cavalry operating with more (singular) independence (Dezső 2012, 15). While there is ill a shield-bearing second cavalryman, this can also engage fully in combat – possibly capable of fighting independently at some level, how- ever this function is to become fully evident after the Ashurnasirpal II period. The third distinct change seen with respect to Assyrian cavalry is that their mounted archers are also equipped, like their Iranian counterparts, with swords. The fourth change pertains to aggression and initiative: Assyrian cavalry are seen in the offfensive again their Iranian counterparts.

The Manna kingdom (formed sometime in c.850 BCE), located in the Lake Urmia region of modern-day Iran’s West-Azerbaijan province, was being subjected to powerful Assyrian raids by the late 9th century BCE. The Medes, already longtime foes of the Assyrians and also located to the east of the Manna kingdom, continued to be subjected to determined Assyrian attacks. Much like his predecessors, Šamši-Adad V’s (r. 823—811 BCE) strategy was focused on undermining (if not destroying) the equestrian base of Assyria’s Iranian enemies. This was done either by seizing their horses on the battlefield or forcing their defeated opponents to surrender their horses as tribute. Following the massacre of 2,300 Median troops of a certain “Anasiruka the Mede” in c. 821 BCE for example, ŠamšiAdad V also captured 140 of their cavalry (Grayson 1996, 185). Meanwhile by the end of the 9th century BCE Manna was to become closely aligned with Assyria due to military threats posed by the kingdom of Urartu (roughly located in mod-

ern-day Armenia in the southern Caucasus and portions of eastern Anatolia).

The Urartians had defeated Assyria and pressed into northwest Iran to seize substantial territory from the Mannaeans and as well as the Persians further south. These serious threats prompted Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 BCE) to implement several governmental and military reforms in 745-727 BCE for the Assyrian army. One of these was the formation of a permanent standing army fully equipped by the state (Melville 2016, 21-55). The Assyrians were already experiencing a military revival just two years before the implementation of the reforms. This may partly explain Tiglath-Pileser III’s 747 BCE successes in Iran, where he penetrated as far as Mount Damavand, near modern Tehran. Just one year into Tiglath-Pileser III’s reforms, the Assyrian army in 744 BCE captured Bit-Hamdan in Western media, making it an Assyrian administered province with taxes imposed upon the overlords of the “country of the mighty Medes” (Dandamaev and Lukonin 1989, 47).

The region of Parsua located in modern-day Sanandaj in Iran’s Kordestan province, south of Lake Urmiah in northwest Iran also became an Assyrian province (Ragnar 2013, 443). However later references to the Parsua made by Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) now identi!es them near Anshan, in close proximity to the Elamites in in Iran’s southwest (modern Khuzistan and Fars provinces) (Farrokh 2007, p.25). Tiglath-Pileser III resumed his military campaigns again! Iran in 737 BCE, where he reportedly received over 1,615 horses in tribute from the Medes and captured large territories inside the Iranian northwest (Dezső 2016, 170, 176), with Assyrian raids reaching near modern-day Tabriz in Iranian Azerbaijan (Ferrill 1985, 77). This is consistent with a !ele discovered in Western Iran reporting of a certain Iranzu (king of the Mannaeans) who was forced to provide tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III.

Notes:

1 Herodotus Histories I, 101.

2 Herodotus Histories I, 125.

3 British Museum, Room B, Slab 27, inventory number: BM 124559.

Autore: Kaveh Farrokh

Fonte: History of Antique Arms

Categorie

Tags